Photo: Nordic Sustainable Construction

2. Decarbonisation policies and current state of carbon declaration and limit values for buildings in EU and the Nordic countries

2.1 Decarbonisation goals and policies

This chapter provides a summary of the national GHG reduction goals defined by the Nordic countries. The goals presented in the tables are carbon reduction in 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2050 or before. The table highlights the targets set by the Nordic countries, as they work toward meeting international binding agreements such as the Paris agreement.

2.1.1 Carbon neutrality goals

Most of the Nordic countries are part of EU’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) or have made commitments to follow the same targets as outlined in the EU’s NDC to the UNFCCC. The Nordic countries have all set goals to become carbon neutral by 2050 or before, following EU regulations. The goals relate to territorial emissions occurring within the country.

Sweden, Finland, Norway, Denmark and Iceland have accelerated the deadline. Denmark (Danish Energy Agency, n.d.) and Sweden (Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency, 2023) aim to become carbon neutral by 2045. Iceland intends to achieve carbon neutrality by 2040 (Government of Iceland, n.d.). Finland (State Treasury Republic of Finland, 2024) has set its sights on 2035 for carbon neutrality. Norway’s target is to become climate neutral by 2030 (Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2021) and aspires to become a low-emissions society by 2050, which involves reducing carbon emissions by 90% to 95% (Ministry of Energy and Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2020) from 1990 levels. Estonia is aiming for carbon neutrality in 2050 (Republic of Estonia Ministry of Climate, 2023).

All the countries are defining carbon neutrality as a balance between carbon emissions and the absorption of carbon from the atmosphere to carbon sinks. To achieve this, the greenhouse gas emissions must be offset by carbon sequestration. It is important to note that the countries’ carbon neutrality goals are based on different reductions achievement goals. Not all the countries disclose the reduction goal for achieving carbon neutrality and simply defines it as the net zero balance between emission and absorption. Sweden is defining the neutrality goal in 2045 with a goal of reducing 1990 levels to 85% lower. Denmark is presenting an ambition of 110% carbon reduction in 2050 compared to 1990 levels. The Finnish climate change act is outlining a goal of 90-95% reduction in 2050 compared to 1990 levels (see Table 1).

Table 1. Carbon neutrality goals. Dark green = carbon neutral target, Light green = carbon reduction

2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | 2050 | |

Denmark | 110%* | ||||

Estonia | |||||

Finland | 90-95%** | ||||

Iceland | |||||

Norway | 90-95%*** | ||||

Sweden | 85%**** | ||||

EU |

*Denmark has an additional goal of 110% reduction compared to 1990 levels in 2050

**Finland’s Climate Change Act outlining a reduction target of 90-95% in 2050 compared to 1990 levels

***Norway’s definition: “low-emissions society” is outlined as 90-95% reduction in 2050 compared to 1990 levels

****Sweden’s Climate neutral goals are based on a carbon reduction of 85% reduction in 2045 compared to 1990 levels.

**Finland’s Climate Change Act outlining a reduction target of 90-95% in 2050 compared to 1990 levels

***Norway’s definition: “low-emissions society” is outlined as 90-95% reduction in 2050 compared to 1990 levels

****Sweden’s Climate neutral goals are based on a carbon reduction of 85% reduction in 2045 compared to 1990 levels.

2.1.2 Immediate carbon reduction goals (2030 goals)

In line with the European Green Deal, most of the Nordic countries have introduced a reduction goal for greenhouse gases (GHG) by 2030. The percentage value of the goal varies across the different countries, however, none of the countries have set a goal below 50% (see Table 2). Norway has a goal of 50-55% reduction of emissions by 2030 compared to 1990 (UNFCCC, 2020). Denmark has made the goal to reduce GHG emissions by 70% in 2030 compared to 1990 (Danish Energy Agency, n.d.). Finland aims to reduce GHG emissions by 60% compared to 1990 levels (State Treasury Republic of Finland, 2024). Iceland aims to reduce GHG emissions by 55% in 2030 relative to 1990 (Government of Iceland - Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources, 2021). Sweden aims to reduce GHG emissions by 63% in 2030 and 75% in 2040 compared to 1990 levels (Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency, 2023). Estonia has no current target for 2030. However, the country has set a target to decrease emissions by 80% by 2035 (Republic of Estonia Ministry of Climate, 2023). Again, all goals relate to territorial emissions within national borders in accordance with IPCC’s methodology for governments to estimate their GHG emissions and removals.

Table 2. Immediate carbon emission reduction goals (2030-goals)

2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | 2050 | |

Denmark | 70% | ||||

Estonia | 80%* | ||||

Finland | 60% | ||||

Iceland | 55% | ||||

Norway | 50-55% | ||||

Sweden | 63% | 75%** | |||

EU | 40% |

* Estonia’s goal is in 2035 instead of 2030

**In addition to the 2030 goal, Sweden have introduced a 2040 goal

**In addition to the 2030 goal, Sweden have introduced a 2040 goal

Photo: Nordic Sustainable Construction

2.1.3 Relation between national emissions reduction and carbon limit values for buildings

Introducing building-specific carbon limit values in regulations aligns with the national emission reduction goals by targeting emissions from the built environment, which accounts for a significant portion of total emissions in many countries. Building-level GHG accounting with LCA relies on fundamentally different accounting principles than national-level reporting based on Systems of Environmental-Economic Accounting (SEEA) (see illustrative example in Figure 1). LCA relies on material and energy flows while SEEA relies on economic data and national reduction goals and usually take a territorial perspective whereas LCA uses a consumption perspective. Therefore, building-level targets cannot easily be compared with national reduction goals. Still, LCA-based building-level targets create a direct push towards decarbonisation in the building sector, which ultimately contributes to fulfilling national reduction targets.

Figure 1. Carbon accounting in building LCA and national reporting methods are two different frameworks whose accounting principles do not align. They are not comparable, but building-level carbon limit values act as a direct tool to ensure that the construction of new buildings is in line with overall decarbonisation efforts in national objectives.

2.2 Dynamics of the building stock

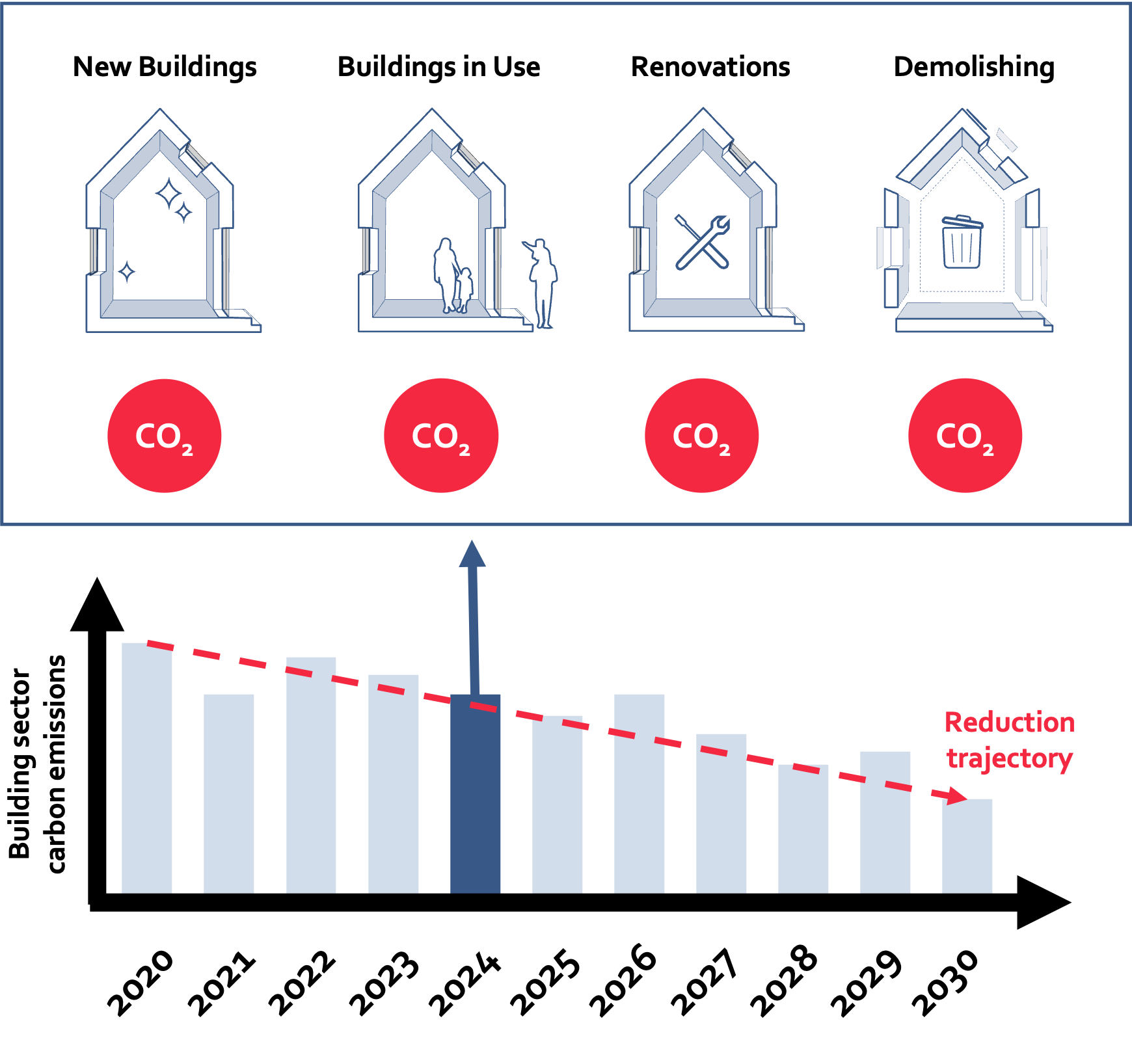

Decarbonisation of the building stock refers to the systematic reduction of carbon emissions associated with buildings over time. To effectively address decarbonisation, it is essential to understand the elements in the development of the building stock over time, here referred to as the dynamic of the building stock. This includes the categories: new buildings, buildings in use and renovations and demolitions, that are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Elements in the building stock dynamic affecting the carbon emissions associated with buildings over time. The figure is illustrative and does not reflect the actual carbon emission level.

New buildings

The number of new buildings constructed and their design are key determining factors for the building sector’s climate impact in the short and long term. It is essential to address new construction both from an efficiency and a sufficiency point of view. New construction should be carefully planned and monitored to ensure that it is carried out where it is truly necessary.

Immediate implications: The creation of new buildings involves the extraction, production and transportation of materials, which collectively contribute to the building’s embodied carbon. Construction processes also generate emissions.

Long-term implications: Once constructed, new buildings determine the operational emissions for decades to come. Their energy consumption for heating, cooling, lighting and power is a critical aspect of the building stock's overall carbon footprint. Incorporating renewable energy sources, high-efficiency systems and smart building technologies can significantly reduce these operational emissions. Design for flexibility, adaptability and disassembly can help decrease future refurbishment needs. The building design and material selection will also lead to different future needs for repair and replacement of materials over the building’s lifetime.

Buildings in use

The ongoing use of buildings is the most significant source of carbon emissions within the building stock, predominantly due to energy consumption for heating, cooling, lighting and electrical appliances.

Immediate implications: Operational emissions are directly influenced by the energy sources used, the efficiency of building systems and occupant behaviour.

Long-term implications: The continuous use and maintenance of buildings offer numerous opportunities for incremental improvements in energy efficiency and sustainability. Over time, these small changes can lead to substantial reductions in the overall emissions of the building stock.

Renovations

Renovations and retrofits of existing buildings are crucial in reducing the carbon footprint of the built environment. Since a large portion of the building stock consists of older structures not originally designed for energy efficiency, renovations can significantly improve their performance.

Immediate implications: Renovation projects can involve updating or adding insulation, windows, heating, HVAC systems, lighting and other building components to reduce energy demand. While renovations may result in some emissions and waste, careful planning and material selection can minimise the impact.

Long-term implications: The improved energy efficiency resulting from renovations leads to reduced operational emissions over the building’s remaining lifespan. Moreover, extending the life of a building through renovation avoids the emissions associated with demolition and new construction.

Demolition

Demolition of buildings plays a pivotal role in the dynamics of the building stock, particularly in relation to decarbonisation efforts. Demolition and waste treatment processes do cause some direct climate impacts (particularly for materials that are incinerated), but the most important consequence of demolition from a climate perspective is that it usually leads to new construction.

Immediate implications: Demolition activities generate considerable amounts of waste, which must be properly treated. While some materials are recycled (e.g., metals), many products end up landfilled or incinerated. Incineration can provide electricity and heat that can be used as energy supply, but the process will also lead to substantial GHG emissions. The demolition process itself also consumes energy and may result in additional emissions from the machinery used, although these are usually small compared to the rest of the building’s life cycle. The deconstruction process can also vary. There is an increased focus on selective demolition where the building materials are recovered with the intention to re-use these in new constructions or recycle the materials to use these and, thus, avoid production of new materials from virgin resources.

Long-term implications: The removal of buildings from the stock creates a demand for new construction. While the newly constructed buildings might be more energy efficient, this will often be far outweighed by the considerable embodied emissions associated with new construction. Indeed, one of the main decarbonisation strategies for the building stock is to preserve and retrofit existing buildings as much as possible to limit new construction.

2.3 European initiatives

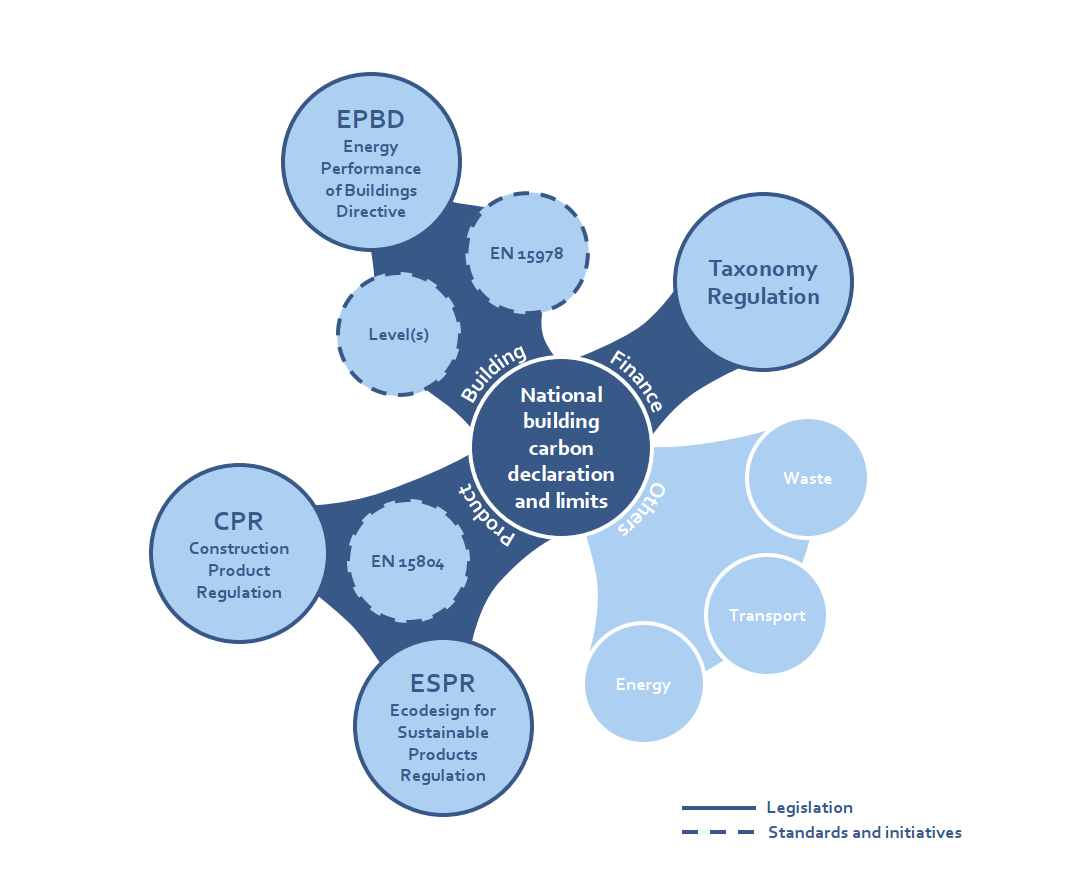

- Several new EU initiatives support national building carbon regulations. They include the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), the Regulations for Construction Products (CPR) and Ecodesign for Sustainable Products (ESPR) and the Taxonomy for Sustainable Investments Regulation. Secondary initiatives include the technical standards EN 15978 and 15804 as well as the Level(s) reporting framework for sustainable buildings.

- These initiatives will, in return, have a significant influence on how national carbon regulations for buildings can be shaped through harmonised limit values for buildings’ climate impact. National carbon declarations and limits will have to operate within the framework given by the EPBD. This includes the full life cycle and building model scope (consistently with Level(s)) as well as definitions for environmental data, scenarios and calculation rules (EN15978, EN15804).

- The European Commission is developing a Whole Life Carbon Roadmap to reduce buildings’ climate impact by 2050, which will contain whole life carbon milestones and targets.

- Two EU member states outside Nordics and Estonia have already introduced carbon limits using alternative approaches including dynamic emission factors (France) and using a single-score weighting of 19 environmental indicators (Netherlands).

National building carbon regulation will be affected by numerous EU regulations and initiatives, see Figure 3.

The revised EPBD (The European Parliament and The Council of The European Union, 2024) requires mandatory whole-life carbon declarations from 2028 for new buildings > 1,000 m2 and in 2030 for all new buildings. National roadmaps for building carbon limits must already be defined by 2027. The declared results must be the total cumulative life-cycle global warming potential (GWP), differentiated in terms of climatic zones and building typologies. The assessment method will be based on the already established Level(s) scheme, which uses the ecosystem of technical buildings standards around EN 15978. Furthermore, all member states need to launch binding carbon limits for new buildings in 2030.

As a consequence, national climate impact declarations and associated limit values will likely evolve to be consistent with the new EPBD carbon declaration, e.g., in terms of which building elements and life cycle stages (i.e. assessment scope) are to be included in the declaration. The scope of included life cycle stages follows the Level(s) indicator 1.2, which are currently under revision. Furthermore, carbon removals associated to carbon storage in or on buildings must be addressed. The latter is expected to be methodologically supported by the quantifying rules for carbon removals currently under preparation within the EU-wide certification scheme for carbon removals.

Figure 3. Key EU regulatory initiatives that affect national building carbon limits. Other areas with indirect impact include energy, transport, waste and many more.

The environmental performance of construction products is key for assessing and regulating building carbon emissions. The first step to improving products is a transparent declaration of the environmental performance. Environmental information on construction products is regulated by the CPR and ESPR, however environmental declaration is not yet mandatory for all construction products. This is why EN 15978 refers to the core product calculation rules in EN 15804 and related standards to fill this gap. Current gaps in product-level environmental information can be filled by national generic environmental data for construction products and voluntary Environmental Product Declarations (EPD) by the industry.

According to the European Green Deal, the EU aims at directing financial flows to sustainable activities, including investments in construction and renovation. The EU Taxonomy supports the transparent classification of activities as sustainable assets. In order to fit the Taxonomy’s criteria, buildings erected after 2023 with a floor area of more than 5,000 m2 must provide a calculation of GWP based on EN 15978 and Level(s). However, these methodologies, in their current version, give room for interpretation, which challenges financial institutions for qualifying green investments in a uniform manner and managing their portfolios efficiently. When mandatory national carbon declarations exist, they can be used instead, which provides more accurate results and use existing consultancy resources. However, a Nordic or international harmonised approach would smoothen financial investments even more.

The EU is developing (as of March 2024) a Whole Life Carbon Roadmap for reduction of buildings’ climate impact by 2050. The roadmap will consist of a series of milestones and targets designed to guide the construction industry in achieving a net-zero carbon building stock. The roadmap will include specific targets for reducing the whole life carbon emissions of buildings, encompassing emissions caused by the operation of buildings and embodied emissions related to building production, construction, renovation and deconstruction. A related technical study (Le Den, et al., 2023) has been published providing information on mitigation strategies and technologies for achieving the necessary EU reduction targets. It shows how the European building sector pathways and strategies can be translated into building-level carbon limits using two reduction scenarios. The TECH-Build scenario assumes the state-of-the-art technological improvements for production processes, efficient design, reuse, recycling, increased use of bio-based materials, etc. The trajectory for building-level embodied carbon in the TECH-Build scenario is shown in Table 3. The LIFE-Build scenario adds additional lifestyle and sufficiency measures such as building less and utilising existing buildings more.

It is important to note that according to the most recent studies analysing samples of existing buildings in Sweden (Malmqvist, Borgström, Brismark, & Erlandsson, 2023) and Denmark (Tozan, et al., 2023), the average upfront embodied carbon values in Table 3 are not representative of the Nordic region because they are very high compared to the average climate impact for new buildings. Considering this, it is necessary to use regional building stock modelling results with care and complement them with national studies of actual buildings.

Table 3. Estimated trajectory of building level upfront embodied carbon and renovation embodied carbon based on archetype modelling and considering the implementation of material efficiencies and technological solutions (so-called “TECH-Build scenario) . Note: “average” represents the average value across archetypes for all regions and building types, “best practice” represents the lowest value observed in any individual archetype. Each archetype covers structural elements, foundations, internal and external walls, floors, stairs, roofs, openings as well as technical and electrical systems. The study applies a 0/0 approach to account for the biogenic carbon content of bio-based materials (no consideration of biogenic GHG uptake, storage and later release in those materials).

2020 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | 2050 | |

Upfront embodied carbon (A1-A5) (kgCO2e/m2 useful floor area) | |||||||

Average | 810.41 | 706.55 | 603.12 | 500.66 | 398.48 | 398.48 | 398.48 |

Best practice | 344.21 | 296.27 | 248.54 | 201.26 | 154.10 | 154.10 | 154.10 |

Renovation embodied carbon (A1-A5, C1-C4) (kgCO2e/m2 useful floor area) | |||||||

Average | 273.81 | 260.30 | 246.60 | 233.62 | 222.06 | 222.06 | 222.06 |

Best practice | 46.81 | 44.51 | 41.93 | 39.49 | 37.32 | 37.32 | 37.32 |

Along with the ongoing development of the regulatory framework in Europe, wider private initiatives increasingly support a harmonised carbon reporting and assessment of buildings (Table 4).

Table 4. Wider industry initiatives supporting harmonised measurements and assessments for buildings’ carbon footprint.

Industry initiatives |

Science-Based Targets Initiative (SBTi): The SBTi developed a sector specific guidance for setting science-based targets (SBTs) for buildings, which is targeted towards companies involved with the building sector. Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM): a tool developed to assess the carbon risk of real estate assets and portfolios by measuring the carbon intensity of their energy consumption and identifying the amount of carbon emissions associated with their current energy consumption. The LCBI Initiative: pan-European low-carbon label measuring the carbon footprint of real estate based on a Life-Cycle Analysis, driven by major European real-estate stakeholders. For embodied carbon, the minimum requirement level to be granted the certification is set to 1,000 kgCO2e/m² for a full-scope LCA, while for exemplary projects is set to 700 kgCO2e/m². The certification also includes benchmarks for the biogenic carbon storage through using of bio-based materials. |

In addition to EU-wide initiatives, individual countries have been pioneering LCA-based mandatory declarations and limit values for newly constructed buildings. The Netherlands introduced LCA-based limit values as early as 2018, using a particular metric called MPG (Milieu Prestatie Gebouwen – Building Environmental Performance). The MPG is determined by first conducting an LCA consistent with EN 15804+A2, including 11 different impact categories. These 11 results are then converted into a single metric expressed in EUR/(m2.year), using a set of standardised weighting factors. In 2018, the MPG limit value was set to EUR 1/(m2.year) for all residential buildings and office buildings over 100 m2. As of 1 July 2021, the limit value for residential buildings was lowered to EUR 0.8/(m2.year). A reduction of the threshold and adaptation of the weighting is expected in 2025, however, no limit values particularly for the climate impact will be implemented in the short-term future.

France introduced a voluntary sustainability label called “E+C-“ (Energy + Carbon -) in November 2016 by the Ministry of Housing, with the purpose of preparing the introduction of mandatory declaration of climate impact. This was a way of trying out an LCA methodology, building up knowledge in the industry and public authorities, and supporting a stakeholder consultation for the introduction of a mandatory declaration. Following this consultation, the method and indicators were revised, and turned into a mandatory energy and carbon declaration with limit values (RE2020). The RE2020 was adopted in 2021, took effect in 2022, and is planned to be updated every three years. The RE2020 requires a separate reporting of life cycle GHG emissions linked to operational energy and emissions linked with materials and on-site activities. It uses dynamic emission factors, which implies that future carbon emissions are of lower importance (and that the temporary storage of carbon in biogenic products provides climate benefits). Limit values depend on the building’s typology, area and location. Overall, the assessment method and reporting requirements are rather complex.

2.4 Nordic initiatives

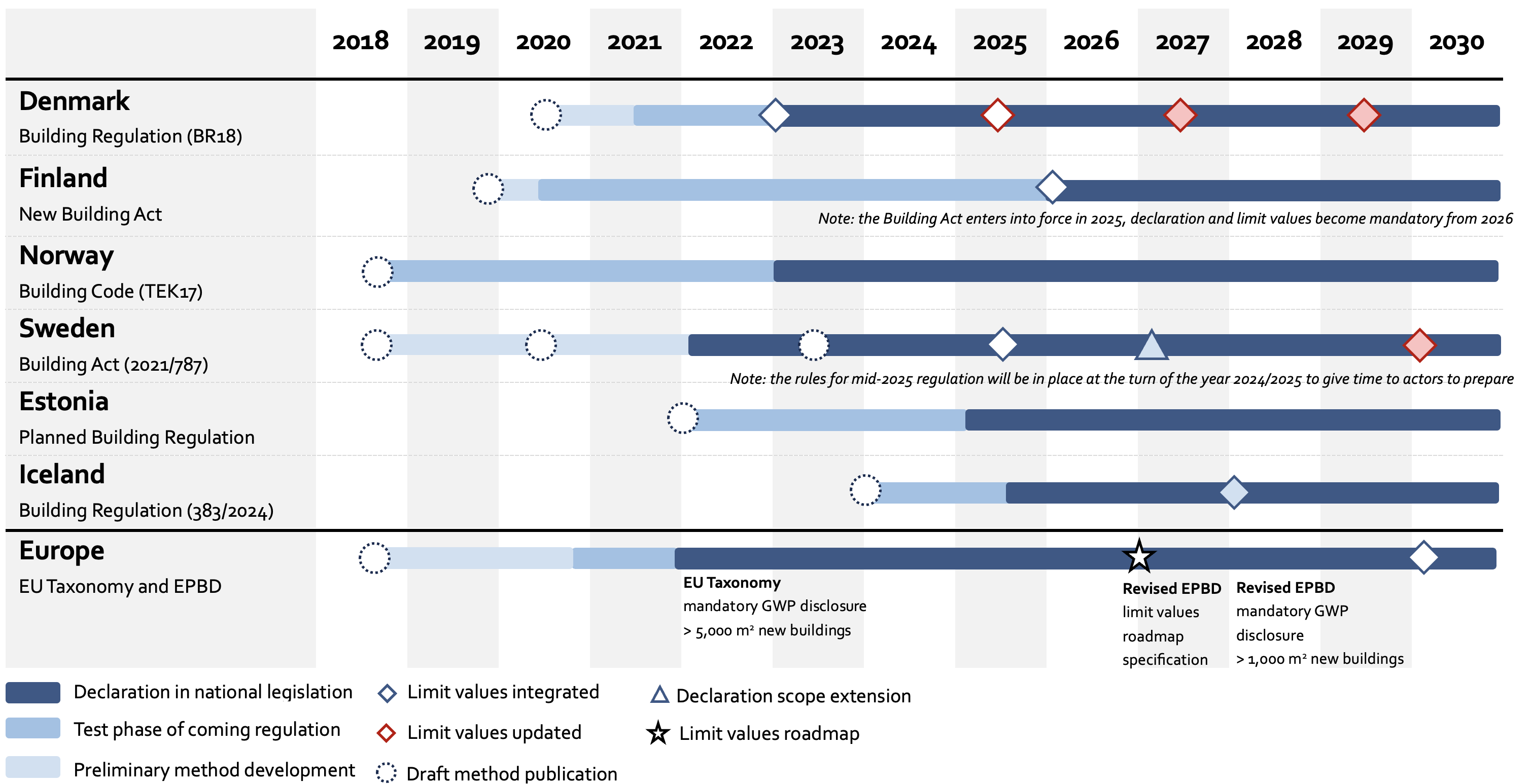

- In all Nordic countries and Estonia, mandatory carbon declarations (with or without limit values) are planned to be introduced by the beginning of 2026. The beginning in mandating carbon declarations was made by Sweden in 2022, the first carbon limit for large buildings was placed by Denmark in 2023.

- The Nordic countries use a limited number of life cycle modules at first implementation to provide industry and investors with a manageable and agreeable method at an affordable cost while preparing them for the decarbonisation transition. However, the EPBD agreement on life cycle completeness according to the full scope of Level(s) requires EU countries to include all stages.

- Aligning with the EPBD implementation, most Nordic countries will need to extend their declaration requirements to all buildings by 2030.

- Some Nordic countries are eager to expand their regulatory requirements to renovations. It is proposed to be incorporated into Sweden’s carbon declaration in 2027 while a stakeholder panel in Denmark recommends a carbon regulation pathway beginning in 2025. Norway already has such a requirement in place.

- Although Denmark initially introduced one limit value for all building types, accompanied by exception rules for specific conditions, differentiation has been adopted for the limit values valid from 2025, as the 40 percent average tightening may begin to put pressure on the way we build.

- Countries with existing carbon regulation require post-completion reporting for achieving a permit for operation, an approach that Finland will most probably follow for its regulation to be effective in 2026. Iceland’s soon-to-be-effective regulation additionally requires carbon reporting at the building permit level, which must then be updated at operation permit level, a practice Estonia is also considering

The Nordic countries and Estonia have initiated a range of governmental activities for planning and implementing carbon declarations and limits for buildings, while industry-led initiatives have helped strengthening the process and general awareness (Table 5). Sweden started mandating carbon declarations in 2022, the first carbon limit for large buildings was introduced by Denmark in 2023, other countries will follow as shown in Table 6. In all Nordic countries and Estonia, mandatory carbon declarations (with or without limit values) are planned to be introduced primo 2026, four years after the pioneering regulation in Sweden. The countries have adopted different timelines for testing the method prior to implementation. The processes and experiences from early implementation of requirements in Nordic countries can provide learnings for other countries. Whole-life carbon limits for buildings are novel and complex and require some preparation of the building sector; a preparation which starts with whole-life carbon assessment competences and routines on the one hand, and cutting carbon emissions by adapting buildings and the construction value chain on the other. The main rationale for national pathways of progressively decreasing limit values is therefore to achieve actual decarbonisation of the building stock, while balancing societal and economic consequences The following chapters show the progress of how the different countries have planned to gradually expand the scope of assessment and the building types underlying carbon regulation.

Table 5. Public policy and industry-driven initiatives related to carbon limits of buildings (as of June 2024)

Government-driven initiatives | Industry (private) initiatives | |

Denmark | National Strategy for Sustainable Construction (2021): Voluntary Sustainability Class for preparing mandatory requirements. Roadmap for carbon declarations and limits for new buildings with progressively decreasing carbon limits by 2023, 2025, 2027, 2029. Background analyses. Carbon regulation in the Danish Building Regulations, sections 297-298 (2023): Mandatory carbon declarations of buildings < 1,000 m2 and carbon limits of buildings > 1,000 m2 | Reduction Roadmap 2.0 (2022): CO2 reduction roadmap for the Danish building sector, initiated by engineering and architectural firms, which aims to align the Paris agreement and the building regulation. Byggeriets Handletank (2024): Proposal for environmental regulation of the Danish construction industry including revised carbon limit values. Green Building Council Denmark’s Certification Manual, 2025: New certification manual for “DGNB Renovation and new build” as a public hearing proposal and pilot project. It includes fewer, but stricter criteria, enhanced focus on performance and promoting renovations and aligning with EU taxonomy |

Estonia | Long-term strategy for building renovation, 2020: strategic plan to renovate 22% of eligible buildings by 2030, 64% by 2040 and 100% by 2050. | Green Tiger Construction Roadmap 2040: construction roadmap that comply with Estonia’s climate goals and secure a stable supply within the construction sector, also suggesting the introduction of limit values in 2027 |

Finland | New Building Act (in force from 2025): to come into effect on 1 January 2025, including measures to streamline the construction process, promote a circular economy and digitalisation, improve the quality of construction and comprehensively address climate change through building legislation. It has been proposed that the carbon declarations and limit values will become mandatory from January 2026. Helsinki initiative: Helsinki municipality has placed a carbon footprint limit for new residential buildings at 16kgCO2e/m²/year) in a 50-year timeframe. The City of Turku has decided to follow Helsinki and will implement the same limit value starting from January 2025. The Circular Economy Green Deal: Government initiative, with Green Building Council Finland (FIGBC) facilitating construction and building sector and further supporting companies in actions taken. Particularly, it is a strategic commitment model, where operators voluntarily commit to goals and measures promoting reduction of natural resource and a carbon-neutral circular economy | |

Åland | Strategy for Sustainable Construction - A sustainable and attractive Åland building stock with a healthy indoor environment (Expected in 2024) | Bärkraft (Åland) Network: network working towards a common goal of a viable and sustainable region, focusing on renovation, renewable materials, energy efficiency and waste reduction, among others. |

Iceland | Icelandic Sustainable Constructions Roadmap to 2030 part III, 2023: a roadmap, which contains reduction targets within the building industry and 74 planned actions to reduce the carbon footprint. It requires a reduction from building materials by 55%, a reduction during the construction stage by 70%, a reduction during the use stage by 55% and a reduction in the end-of-life stage by 88% to 95%. Regulation on an amendment to the building regulations (2024): According to this amendment, as of September 1, 2025, it will be mandatory to carry out life cycle analyses for new buildings in scope categories 2 and 3. | |

Norway | Byggteknisk forskrift, TEK17, §17 (2022): describes the regulations on technical requirements for buildings in Norway and includes a chapter (i.e., 17) with the LCA requirements for buildings. It also forbids use of fossil energy in new buildings. Regulations prohibiting the use of mineral oil for heating buildings: In 2020 it was forbidden to use fossil oil in existing buildings. In 2022 it was forbidden to use fossil oil to temporally heat buildings under constructions. Climate partnership, 2023: a climate partnership with stakeholders from the construction sector to develop a knowledge base through workshops. In 2024 Norway started to evaluate if regulatory measures to reduce climate footprint, including limit values should be implemented | FutureBuilt: innovation programme intended to showcase the most ambitious projects that can push the sector to get aligned with the Paris agreement carbon targets. It includes a defined criteria set for buildings with specific whole life cycle limit values and that are dynamic with ever more stringent limits depending on construction year. The programme has several large municipalities and various authorities as partners but is also widely used by private real estate actors. DFØ’s reference buildings: The public procurement authority (DFØ) has compiled a set of reference buildings of standard construction methods. These buildings are used to calculate reference limit values that are widely used in the sector (BREEAM NOR among others). |

Sweden | Act on Climate Declarations for Buildings (2021): it came into effect on 1 January 2022. The Act applies to new buildings for which planning permission is sought from that date onwards. Boverket limit values: the national board of housing, building and planning (Boverket) proposes a GHG limit value for carbon declarations on new buildings in the construction sector for the earliest by July 2025. As of June 2024, the Swedish Housing Authority agreed that the new rules will come into force on 1 July 2025, with a transition period until mid-2026 when one could choose between applying all new regulations or older regulations. The specific rules will be in place at the turn of the year 2024/2025 in order to give the actors the opportunity to prepare. | Fossilfritt Sverige (Fossil Free Sweden): Collaborative effort among companies, municipalities, regions and organisations to accelerating the pace of the climate transition. 22 different business sectors have developed roadmaps for fossil-free competitiveness. The construction and civil engineering sector strives for a 50% reduction of GHG emissions until 2030. National Procurement Authority: this Authority has criteria for procurement on lowering the climate impact from buildings. For example, the climate impact from each project must be at least 40% lower than the calculated baseline solution for the project or not exceed 235 Kg CO2e per m2 of gross floor area. |

Table 6. Timeline of carbon declaration and limit values integration (as of June 2024). The existing and proposed limit values follow different methodologies. More details can be found in Table 15. The symbols filled with colours indicate that the exact date of introduction of the indicated activities is still open and subject to political negotiations

2.4.1 Trajectory to full life cycle scope

Two distinct strategies are observed in order to facilitate the adoption of carbon declarations and limit values at the time of their introduction. (a) First introducing a declaration without limit value, and then introducing a fairly ambitious limit value after some years of evaluation (i.e. Swedish approach), or (b) introducing a limit value early in the process, but ensuring that the first-generation limit value can most often be met by conventional building solutions without adaptation efforts; limit values will then have to be reduced over time (i.e. Danish approach) – see Table 7.

Table 7 Detailed planned integration of carbon declaration and limit values for the two Nordic countries (Denmark and Sweden) with concrete suggestions in place (status as of June 2024). For each country, the top layer shows an overview of the limit value(s)-related plans, while the bottom layer provides the planned activities for declarations. Most decisions from 2025 are still open to political negotiations.

2022 | All new buildings A1-A5 | |||

1/10 buildings to perform better New buildings > 1,000 m2 12 kgCO2e/(m2 yr.) A1-A3, B4, B6, C3-C4 | 2023 | |||

All new buildings A1-A3, B4, B6, C3-C4 + D | ||||

2024 | ||||

17/20 buildings to perform better New buildings/Extensions > 50 m2 Extensions for small houses > 250 m2 4-8 kgCO2e/(m2 yr.), building type dependent Average: 7.1 kgCO2e/(m2 yr.) A1-A3, B4, B6, C3-C4 Construction process: 1.5 kgCO2e/(m2 yr.) A4, A5 | 2025 | 1/2 buildings to perform better New buildings > 100 m2 180 kgCO2e/m2, 1-or 2-family houses, A1-A5, ~3,6 kgCO2e/(m2 yr.) for 50 years RSP 330-460 kgCO2e/m2, building type dependent, A1-A5, ~6,6-9,2 kgCO2e/(m2 yr.) | ||

2026 | ||||

~ 10% ↓ Likely inclusion of outdoor areas** Potential extension to further life cycle modules (B1, B2, C1, C2) following European developments** | 2027 | New buildings and deep renovations A1-A5, B2, B4, B6, C1-C4 | ||

2028 | ||||

~ 10% ↓ | 2029 | |||

2030 | 15% ↓ 1-or 2-family houses 25% ↓ other building types | |||

* Initially planned tightening to “1/3 buildings to perform better” **still open to political negotiations | ||||

Unlike the Netherlands and France, which already have undergone a preparatory and evaluation process, the Nordic countries use a limited number of life cycle modules at implementation. This decision is a compromise between preparing industry and investors for the decarbonisation transition on the one hand and introducing an agreeable and manageable method at affordable cost on the other. Denmark already announced the consideration of two additional modules (A4 and A5) in the 2025 assessment scope (new rules to come into force on 1 July 2025), and Sweden plans to extend the current system boundary with more life cycle modules towards a more complete life cycle scope in the future (new rules to be in place at the turn of the year 2024/2025 and come into force on 1 July 2025), while Finland and Iceland are planning to include the most relevant modules from the beginning. The EPBD agreement refers to the total life cycle, Annex III (The European Parliament and The Council of The European Union, 2024), which is likely the prospect for the member state implementation, at least regarding carbon declarations. A more detailed view on this aspect is provided in the method-focused Section 4.2.

2.4.2 Trajectory to full coverage of building types

In the Nordic countries, most new buildings are being built for residential purposes, however, offices, institutions and other uses also have a considerable share of new construction and may therefore have significant climate impacts. While building typology, construction method and subsequent climate impacts are varying considerably within the individual use categories of i.e., schools or apartment blocks, building use, meaning the delivered function, is applied as the categorisation factor for carbon regulation in the Nordic countries. The remaining justified variation within each use category (i.e., urban area versus country-side school) should be considered by other means, for instance through an allowance for components with extraordinary high climate impacts, as in the case of the Danish Building Regulations.

Currently, Denmark includes all at least partially heated building uses except for agriculture. However, carbon limits only apply for buildings above 1,000 m2 in the initial implementation phase. According to the new agreement (effective May 2024) for 2025 limit values, all types of new buildings are covered, whether heated or unheated, with the exception of socially critical buildings and unheated buildings under 50 m2. Norway excludes detached homes and other small homes like semi-detached houses, town houses and small terraced houses. Finland excludes single family homes in the beginning. Sweden has detailed rules excluding industrial and agricultural buildings, buildings constructed by private individuals without business purposes, as well as buildings necessary for safety and defence. In Iceland, all new buildings are subject to the new requirements, except for small new constructions such as storage facilities, summerhouses, cabins, detached garages and guesthouses.

The latest limit value studies in Sweden (Boverket, 2023) and Denmark (Tozan, et al., 2023) demonstrate a significant difference in climate impact level dependent on building use, which suggests individual limit values for building uses (see Table 8). A differentiation would secure an appropriate balance between reduction goals and decarbonisation potential in each use category. Accordingly, Denmark introduced differentiated limit values for building types from 2025 to ensure that buildings with a lower climate impact are as motivated to reduce emissions as those with a higher climate impact. This aligns with the current EPBD proposal, which specifically includes all energy-consuming buildings and requires carbon limit roadmaps separated into different building uses.

Table 8. Building uses and sizes covered by the current and proposed requirements (as of June 2024). Note: Iceland plans to include limit values in its regulation by 2028, however it has not been determined whether these will initially focus on a limited number of building types and sizes. Therefore, the table only provides information about the upcoming carbon declarations in this case.

Building TYPE | Denmark | Estonia | Finland | Iceland9 | Norway | Sweden | Europe (EPBD) |

Single-family home | ✓ | ✓ | ✓1,2 | ✓ | |||

Other residential building | ✓ | O | O | ✓ | ✓ | ✓1,2 | ✓ |

Office | ✓ | O | O | ✓ | ✓ | ✓1,2 | ✓ |

Retail and restaurant | ✓ | O | O | ✓ | ✓ | ✓1,2 | ✓ |

School and daycare | ✓ | O | O | ✓ | ✓ | ✓1,2 | ✓ |

Laboratory | ✓ | O | O | ✓ | ✓ | ✓1,2 | ✓ |

Hospital and health | ✓ | O | O | ✓ | ✓ | ✓1,2 | ✓ |

Sports facilities | ✓ | O | O | ✓ | ✓ | ✓1,2 | ✓ |

Cultural and other public | ✓ | O | O | ✓ | ✓ | ✓1,2,8 | ✓6 |

Religious | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓1,2 | |||

Industrial | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓6 | |||

HOLIDAY cottages5 | from 2025 | ✓4 | ✓1,2 | ✓ | |||

Other | ✓7 | O | ✓ | ✓ | ✓1,2 | ✓6 | |

Renovation projects | ✓ | ✓ | O3 | ||||

Size of buildings | 2023-2025: > 1,000 m2 From 2025: > 50 m2 for unheated buildings; > 250 m2 for extensions of single family, terraced and holiday houses | unspecified | no size requirement, except for warehouses, transport and communications buildings, indoor swimming pools and indoor ice rinks (> 1,000 m2) | unspecified, buildings under scope classes 2 and 3 in Building Regulation | no size requirement, just building type | > 100 m2 | 2028: > 1,000 m2 From 2030: > 50 m2 |

| |||||||

A great interest in learning more about the climate impact of deep renovations is observed in Nordic countries, with Boverket proposing to include deep renovation projects such as building remodelling or repurposing in the carbon declaration in Sweden from 2027, a requirement already in place in Norway. A stakeholder panel in Denmark has recommended a pathway for carbon regulation starting with carbon declarations of large renovations in 2025 and eventually leading to limit values by 2027. However, discussions and analyses are ongoing and no official policy for additional carbon regulation of renovations has been issued. The rationale for excluding deep renovations in the initial stages of regulation implementation is based on simplifying the workload of building supervision and streamlining the permit process. However, excluding renovation construction from carbon assessments could undermine the environmental impact of the renovation construction market and impede the development of new low-carbon innovations. Consequently, this could have a significant impact on the achievement of carbon neutrality goals set at both national and EU levels.

2.4.3 Compliance control regime

The envisioned decarbonisation goals for construction can only be achieved when minimum carbon limits are met. Thus, an appropriate compliance control regime is a must when planning carbon regulation. The need for verification and sanctions for infringement depends on the specific regulation approach including the required reporting stage (building permit or use permit), the detail of reporting requirements and who is authorised to check them. Key reporting elements include the building component inventory, operational energy calculations, scenarios, environmental data and the calculation procedure.

In order to avoid the risk of infringement, both sides of the compliance regime, the construction value chain and the building authority, have to be considered for achieving an efficient procedure. This is achieved by balancing the reporting requirements with the expected stakeholder preparedness. A way of reducing reporting workload, the risk for error in reporting and the need for external verification is narrowing down the methodological choices to the necessary minimum. Professional tools can improve reporting feasibility and ensure quality in the assessment workflow. Here, a part of the quality management is delegated to the tool providers. Since the EPDs are only available for parts of the construction product supply, generic environmental data for building products can fill the data gap and simplify the modelling process. Table 9 gives an overview on similarities and differences in control regimes for building carbon regulation in the Nordic countries.

In all participating countries, control routines are about to be developed as the requirements are being implemented. Sweden has published information about their process for supervision. Since the building life cycle spans require data from different sources and actors, the balance between effective and feasible procedure will take several years to test and refine. Countries with existing carbon regulation require post-completion reporting for achieving a permit for operation. Iceland’s regulation, effective from September 2025, will require carbon reporting at the building permit stage, which will then need to be updated at the operation permit stage. Estonia is also considering a similar approach. No country requires the use of a specific official tool.

Table 9. Relevant factors for correct reporting and compliance control (in force or planned)

Denmark | Estonia | Finland | Iceland | Norway | Sweden | |

BR18 | Proposed | Proposed | Proposed | TEK17 | Boverket | |

Reporting stage | As-built | Building permit | As-built | Building permit + As-built | As-built | As-built |

Technical compliance control | 10% of cases checked | Not yet decided | Not yet decided | Random checks | Yes | 10% of cases checked** |

External verification | No | Not yet decided | Not yet decided (possibly BIM file) | LCA result is handed in an excel format to HMS* | No | No |

Market-based tools allowed | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Environmental product database | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

*Iceland’s Housing and Infrastructure Agency ** Boverket proposes that 100% of carbon declarations are controlled when limit values are introduced (Boverket’s report 2023: 24). This can be achieved by comparing the digitally registered climate impact with the reference value for the building type, i.e., comparing the calculation base submitted by the developer with the calculation base for the reference building, and then performing a reasonability assessment for the correct calculation. | ||||||

Being a keystone in carbon declarations, the systematic reporting of the building fabric demands for a harmonised building classification system that would be beneficial for ensuring that impacts and quantities are assigned to building parts in a uniform manner. Today, all countries have different systems, while some use a variety of systems. The correct use of classification is a precondition to being able to perform control and related delivery notes and other product documentation to the model.