8. Discussion and Conclusion

As pointed out by the EU's Scientific Council (2024), most policy instruments traditionally have been technology-focused and aimed at the supply side. There are however several examples of demand-side policy instruments, e.g. carbon taxes on fossil fuels.

In addition to the direct effects linked to individual behaviour (like driving or heating and cooling your house), changed behaviours can potentially impact emissions ‘upstream’ (activities that produce consumer goods, including from imported goods) as well as ‘downstream’ (e.g. emissions arising from waste disposal). This also means that changes in behaviour can impact ‘embodied’ emissions in imports as well as domestic production (Grubb et al., 2020).

Moran et al. (2020) estimates that opportunities from changes in consumer behaviour could reduce the EU’s overall carbon footprint by about 25%. Thus, substantial reductions, crucial for reaching nationally as well as internationally set mitigations targets can be achieved with existing technologies already in place. This is also in line with a Swedish study focused on food, holiday travels and furniture (Carlsson-Kanyama et al., 2021). The original call from the Nordic Council of Ministers suggested to limit the study to policies targeting consumption of electronics, food, textiles and home furnishings (or rather emissions of GHGs and other air pollutants stemming from this consumption). This turned out to be immaterial since very few policies were this specific. In order to conduct a broad survey and report substantial results, we had to broaden our scope to other categories of consumption.

New Policy Instruments May Be Politically Sensitive

Consumption-oriented policies could be necessary as well as cost-effective ways to reduce emission. They are however less common, partly because it is politically sensitive to point at individual behaviour and how these behaviours should change.

Acceptance of policy instruments is necessary for their implementation. This acceptance is needed both among decision-makers and the general public (Ewald et al., 2022; Coleman et al., 2023). Acceptance of policy instruments can increase if multiple instruments are combined, e.g. in packages containing both carrots and sticks. Combining reduced consumption, or reduced emissions from consumption, with other goals, such as improved health and lower household expenditures, can also be effective as a driver of change (Tobi et al., 2019). For example, there might be more positive response from a message highlighting the health aspects of a certain diet, rather than focusing on its environmental effects. Additionally, the order in which policy instruments are introduced can affect how they are received and their effectiveness (Meckling et al., 2017). In this project, we compiled policy instruments aimed at consumption and analysed them in terms of effectiveness and feasibility, to ultimately provide policy recommendations.

Consumer-based policy faces several challenges in design and implementation. One challenge is the political risk associated with targeting households and private consumers, i.e. to tell individuals what to do and place responsibility of action and the potential economic burden on households instead of companies and governments. Consumption based policies thus have a potential for controversy (Schanes et al., 2019; Grubb et al., 2020). Thus, consumer policies have to be transparent and supported by the same democratic processes, public debate and critical scrutiny of their costs and benefits as are other policy instruments.

One example of a recent public debate over a consumer policy is when the Nordic Council of Ministers’ secretary general Karen Ellemann launched the idea of a tax on meat and sugar coordinated across all Nordic countries. Ellemann (2024, our translation) argues: “If the Nordic countries jointly implement these types of policy measures, it can increase public acceptance, which often poses a challenge. Acting together can also reduce the risk of trade simply shifting across borders and simplify things for the food industry by having similar regulations and conditions in all Nordic countries”. The value of this proposal, however, was immediately disputed by Finland, Norway, and Sweden’s Ministers of Agriculture (Essayah et al., 2024, our translation): “A Nordic meat tax is completely the wrong approach.” The ministers continued: “Developing a meat tax would hit Nordic agriculture hard – to the detriment of both farmers, the climate, and consumers.” This example illustrates the political sensitivity around introducing consumer policy targeting food.

It is however interesting to note that all the Nordic countries have a significant number of consumption-oriented taxes and other policy instruments in place which have widespread acceptance. One example is the VAT which in some countries also is differentiated between different product groups. Other examples include taxes on alcohol and tobacco products. In addition, there are other types of policy instruments for these products including regulations on when and how the products can be sold and on advertising. Among the environmentally oriented consumer-oriented policies there are CO2 taxes on fuels and bans on certain hazardous chemicals. All these policy instruments have, in general, a high acceptance in the Nordic countries. This suggests that it should be possible to increase the number of consumer-oriented policies for environmental purposes.

Conclusions from the Policy Delphi

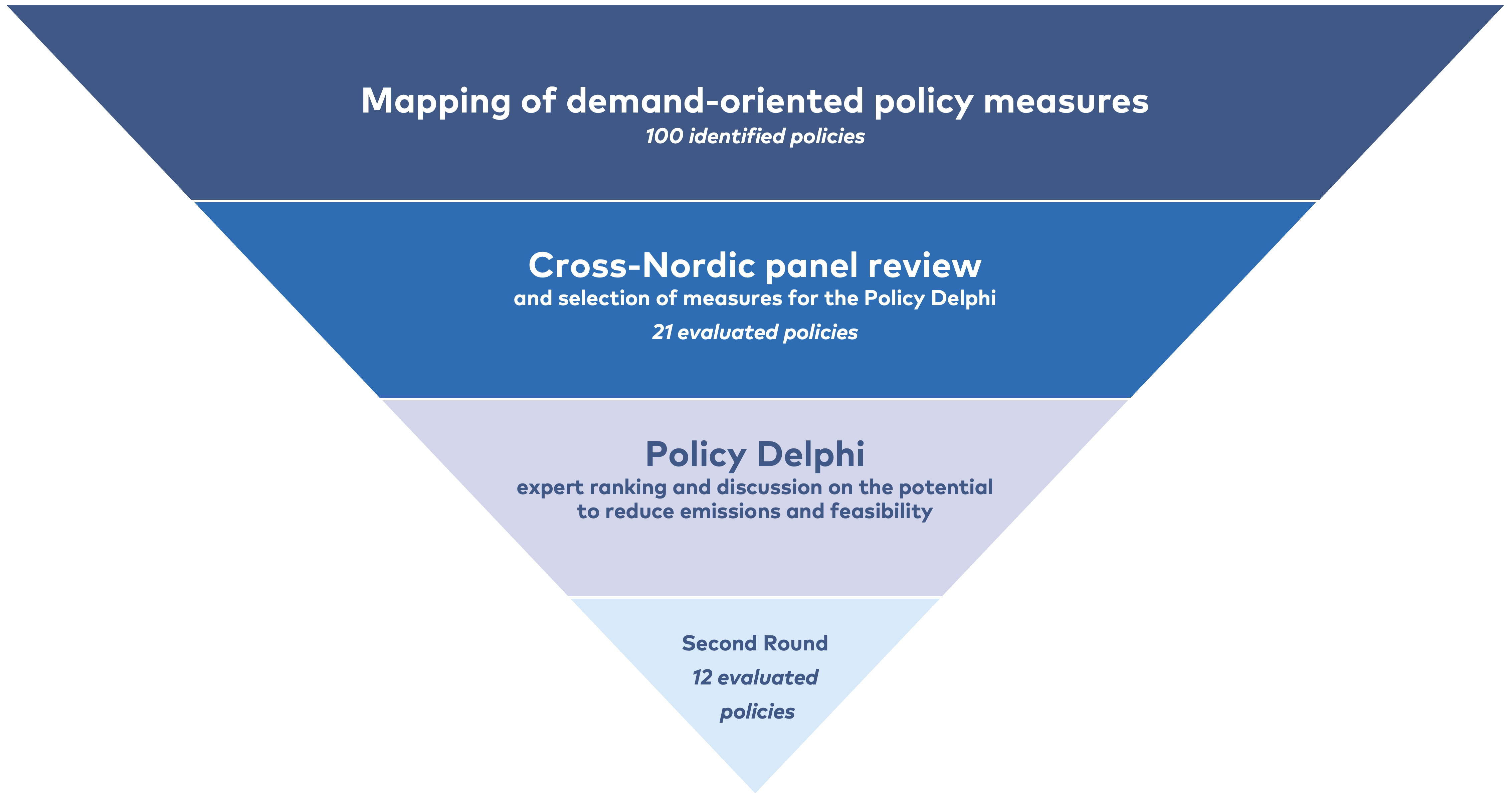

In the process of identifying effective and feasible policies, we assembled a longlist of policies that are either in use today, have previously been used, or have been discussed in the Nordic countries. This list contained approximately 100 policies which are briefly described in Table 6. A cross-Nordic panel (listed as the authors of this report) was used to review the mapping and select 21 policies with high potential and feasibility for the Policy Delphi. In the Policy Delphi, 23 experts were invited in two consecutive rounds to rank policies according to their potential to reduce emissions and their feasibility.

Figure 14. From the longlist of policy measures to the shortlist of policies identified as most promising through a review of Nordic experts and a two round Policy Delphi.

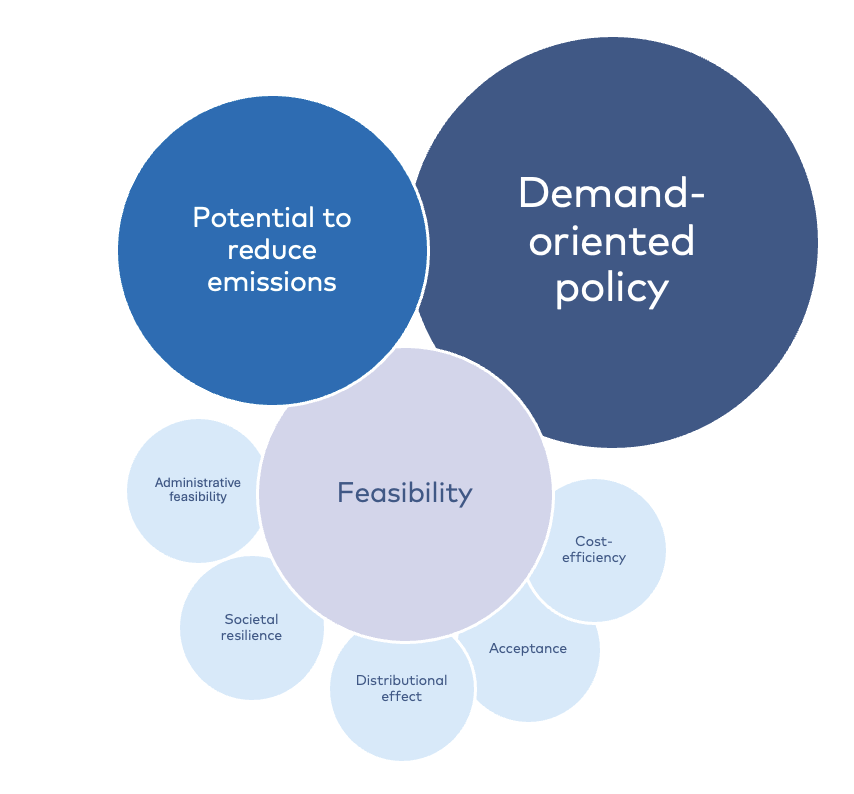

When considering the potential to reduce emissions and the feasibility of the different policies, the respondents were instructed to consider distributional effects, feasibility and legal constraints, as requested by the Nordic Council of Ministers. They were also asked to consider efficiency in reducing emissions, cost-effectiveness, and acceptability. In Figure 15, we have modified the model illustrated in Figure 1 in the introduction to include these aspects. The model also illustrates that acceptance is closely linked to perceived distributional effects and, in turn, the feasibility of a policy instrument. Thus, according to the respondents, the policies most interesting in terms of reducing emissions of GHGs and other air pollutants scored relatively high in most of the aspects of Figure 15.

Figure 15. Policy for Consumption-Based Emissions (extended version)

Not all policies that were highly ranked by the experts were selected for the second round. One example of a policy scoring high on both potential to reduce emissions and feasibility was the CO2 border duty CBAM (Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism). This policy is however not a national competence - it is decided upon at EU-level. Following this, CBAM was not included in round 2 of the Policy Delphi. Neither was Conditioning tax deduction for home repairs. This policy suggestion will not result in increased expenses for the government. On the contrary, it is an example of reducing a subsidy for activities causing emissions. The proposed policy thus has the potential to save governmental expenses as well as to reduce emissions. However, following comments from the experts, it was seen as too difficult to discriminate between home improvement investments that will decrease, or increase, emissions/related environmental impacts associated with building.

The 12 policies in round 2 are fairly evenly distributed across different categories of policies (see Table 7). Three can be categorised as information policies. Four of the policies concern taxes and three are examples of subsidies. One policy, fee and dividend, qualifies for both the tax and the subsidies categories. Three policies are categorized as regulations. These three are rather different. A ban on short flights does not have much in common with regulatory standards or public procurement. This is a simple and straightforward way of categorising, but one could argue that the categorization should be done differently. For example, reduced incentives for commuting to work by car is, of course, as much a regulation as a reduced subsidy or tax deduction, and public procurement could not be performed without taxes.

Table 7. Categorizing the twelve policies in Policy Delphi round 2

Policy | Labelling or other information | Tax | Subsidy, dividend or tax deduction | Regulations including ban | Climate related | Other air pollutants |

Frequent flyer tax | X | X | X | |||

Product labels | X | X | X | |||

Advertising regulation | X | X | X | |||

Fee & dividend to low-income households | X | X | X | X | ||

Ban on short flights | X | X | X | |||

Carbon tax | X | X | X (indirectly) | |||

Consumer guides & dietary advice | X | X | X | |||

Consumption taxes | X | X | X | |||

Subsidies to increase demand for low emission products | X | X | X | |||

Reduce incentives for commuting to work by car | X | X | X | |||

Public procurement | X | X | X | |||

Regulatory standards | X | X | X |

Reduced incentives for commuting to work by car do not result in increased expenses for the government. On the contrary, it most likely would save tax money as well as reduce environmental damage. As practiced in Sweden today, the tax deduction for commuting by car is a textbook example of a perverse incentive

All twelve policies in round 2 of the Policy Delphi are related to climate. All of them impact at least indirectly other air pollutants as well. This is because, as discussed above, many airborne pollutants stem from the combustion of fossil fuels. Targeting transportation, e.g. flying or commuting by car, will have positive effects beyond the reduction of GHGs emissions. Policies that increase demand for biofuels could be an exception, since the incineration of biofuels emits air pollutants including NOx and PM.

One reflection is that several of the 12 policy options do not directly target consumption. Another reflection is that some policies focus directly on greenhouse gases and only indirectly on other air pollutants. Of course, general policies such as public procurement, regulatory standards and consumption taxes, could be geared towards any environmental issue. A third reflection is that out of the studied policies, quite a few policies target transportation (see Tables 6 and 7 above), which initially was not a main objective of this study. Two out of the twelve policies directly concern flying – a frequent flying tax and a ban on short flights. Few policies in the compilation of policies directly target food consumption, electronics, textiles or home furnishing, which were specified areas of consumption to study following the call. Whether this is a sign that these areas are neglected, or if they are covered in other ways in environmental policy, is out of the scope of this study.

Pros and Cons of Consumption Taxes

When using economic policy measures, such as taxes, it is generally accepted that it is most cost-efficient to place the tax on emissions. This approach provides both producers with incentives to reduce emissions and consumers with incentives to lower their consumption of high-emission products, as these become more expensive due to the emission tax. If consumption is taxed instead of emissions (for example, taxing beef instead of methane emissions) it does not directly incentivize producers to mitigate emissions.

However, there are several exceptions where consumption taxes are worth considering (Morfeldt et al., 2023). One example is when international agreements prevent the taxation of emissions. This is the case for international aviation. Another example is when monitoring costs related to emissions are prohibitively high (Schmutzler and Goulde, 1997), as may e.g. be the case with methane emissions from the agricultural sector.

Especially for small, open economies, such as the Nordic countries, it is also important to consider that emission taxes can lead to decreased competitiveness for domestic producers, resulting in increased imports and job losses, but not necessarily any reduction in global emissions. These “leakages” can, at least in part, be reduced by providing subsidies to farmers and other producers, as has been proposed in Denmark along with a methane tax (Svarer, 2024). The leakages can also be reduced by taxing consumption instead of emissions.

It is also important not to conflate the relatively high consumption taxes required to generate substantial emission reductions with high societal costs. When collecting consumption taxes, other taxes can be reduced or the tax revenues can be used for subsidies or other purposes benefitting society. The same is true for emission taxes. It is unclear how the economy and employment would be impacted by high consumption taxes on, for example, beef and air travel, which would depend on how the tax revenue is spent (this could include corresponding reductions in income taxes and/or increases in transfer incomes or public consumption.)

Policy Recommendations

Our main message is that available consumption-based emissions statistics and trends motivate and support policy action. This action could be further supported by improved statistics, clear policy ambitions and Nordic cooperation. Furthermore, our mapping shows that there is no lack of possible options for policymakers that seek to reduce consumption-based emissions. Here we have used Nordic experts to identify a longlist of current and potential consumption-based policies, to rank and evaluate 21 different policies, and to identify a number of particularly promising policies, detailing possible barriers and enabling aspects. We recommend further analysis to combine promising policies in actionable and effective packages.

Improve Statistics and Set Clear Ambitions

Across Nordic countries, we see a number of efforts to publish consumption-based GHG emissions statistics. Sweden has been at the forefront for many years, publishing data on consumption-based GHG emissions as part of its official statistics. Finland and Denmark also publish annually official consumption-based GHG statistics. The Norwegian Environmental Agency published its first estimation of consumption-based emissions in 2024, while Iceland relies on research estimates. Consumption-based emissions accounts of other air pollutants are lacking in most studied countries. The capacity to compare emissions statistics across the Nordic countries is limited, as the consumption-based GHG emissions statistics are produced using different methods and databases. Better statistics could improve this situation on the EU and international levels and efforts are underway in this direction (Guilhoto et al., 2023).

In all Nordic countries, there are policies in place to reduce the consumption-based emissions of GHGs and other air pollutants. In Sweden, a target has been proposed by the parliamentary Environmental Objectives Committee to have a negative global climate impact by 2045. Similarly, the Danish Council on Climate Change (2023) has proposed setting national benchmarks for reducing consumption-based emissions. Moreover, clear national ambitions could support local targets already being put into place, for instance by Swedish municipalities.

Pursue Nordic Cooperation

Emissions imported to the Nordics, to a high degree, originate from major trading partner countries, including Germany, USA, and China. A non-negligible amount of exported and imported emissions are inter-Nordic (e.g., circa 4% of Sweden’s consumption-based GHG emissions originate from Denmark, Finland and Norway combined). In this way, the Nordic climate transitions are interconnected. If production-based emissions in one Nordic country are reduced, it will help the other Nordic countries to reduce their consumption-based emissions. Correspondingly, failure to transition key exporting industries may have repercussions in importing countries. For example, Sweden’s steel exports and Denmark’s exports of agricultural products are important not only for Sweden and Denmark, but also for the importing countries. Furthermore, if the Nordic countries can uphold a leadership position on climate, increased Nordic trade is also likely to reduce consumption-based emissions, as these imports will be less emissions intensive (e.g., compared to imports from China).

To attain leading positions, ambitious consumption-based climate policies are necessary. These include consumption taxes on high GHG-emitting items including beef and air travel. Implementing these taxes in one country may lead to tax avoidance strategies by consumers or companies, such as purchasing meat or flying from neighbouring countries. However, the impact of such avoidance strategies should not be exaggerated, as they typically require additional time and effort compared to local purchases. Minimizing this issue is possible by aiming for tax harmonization among the Nordic countries.

Take Advantage of the Longlist of Possible and Promising policies

Both the IPCC (2023) and the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change (2024) underscore the need for demand-oriented climate mitigation, supported by the statistics presented in this report. In our mapping, we have identified around one hundred consumption-oriented policy measures that can be used to reduce emissions (see Table 6). This broad spectrum of policies indicates that there is no silver bullet, but ample opportunity to select multiple policies which support each other in broader policy-packages. Circumstances and political priorities vary across and within the Nordic countries, but the wide set of policies shows that there are many ways forward.

Areas of policy measures include informational, regulatory, administrative and economic policies. The debate on sustainable consumption could benefit from acknowledging the wide range of means to reduce demand and consumption-based emissions, which does not limit itself to informational campaigns or raised consumption taxes. Moreover, most of the identified policy measures have been implemented in some form, showing that consumption-based policies are not a new arena for environmental policy-making. Potential policy strategies, including policy packages, would have to be supported by clear conceptions of how policies would interact, and how they should be package.

Using expert rankings and commentary, we have identified particularly promising policies (see method section on the Policy Delphi method). The policy instrument which was awarded the highest overall ranking was regulatory standards. National laws that regulate pollution produced by a particular production process, or product, is a common and well-proven policy approach. Yet, this is an approach which the experts find worth developing further, because it has a high potential to reduce emission and because of its high feasibility. Regulatory standards are also possible to harmonize on a Nordic level. It is an area where the EU is moving ahead with, e.g., the Ecodesign Directive. Public procurement is awarded a similarly high ranking. Policies which target public procurement to achieve sustainability objectives are in place in all the Nordic countries, yet the experts see great potential for emissions reduction in using such instruments more.

Two instruments which are of EU, rather than national, competence was selected for the first round of the Policy Delphi because of their high relevance for decreasing consumption-based emissions. These instruments were also highly ranked by the experts. However, they were excluded in the second round to give space to deepen the analysis of national policy instruments. One of the instruments was Extension of Product Lifetime, which is understood as having high public acceptance while also bringing the co-benefit of reducing material demand. The second instrument was the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms which, has gotten a lot of attention in recent years and “will apply in its definitive regime from 2026, while the current transitional phase lasts between 2023 and 2025” (European Commission, no date).

Highlighting the need, not only to implement instruments targeting emissions, but to remove perverse incentives encouraging increased emissions, the experts rank reduced incentives for commuting to work by car highly. Road transport makes up a large portion of the consumption-based GHG emissions, and negatively impact air quality and health in cities.

Furthermore, the experts see a large potential in using subsidies to increase demand for low emission products. Such subsidies could be viewed as “carrots” to choose less emission intensive products. Subsidies can reduce prices of product segments and have the potential to stimulate new markets. For instance, Norwegian EV subsidies to encourage market growth for these products could further benefit other Nordic countries.

Consumption taxes are also among the highest ranked policy measures. Consumption taxes are extensively debated in both the academic literature and political contexts, concerning levels, design and areas of application. We do not engage further in such debates here, our recommendation is limited to the expert’s opinions, which firmly establish consumption taxes as potentially very effective and a key part in broader policy strategies.

Table 8. High ranking “promising policies”

Table 8. High ranking “promising policies” | ||

Policy instruments | Mean ranking | Enabling aspects (+) and possible barriers (-) |

Regulatory standards | 3.9 | + same rules for all + generally high feasibility and potential to reduce emissions - works better for few large producers than for many small - risk for production moving to other countries |

Public procurement | 3.9 | + generally high feasibility and potential + substantial indirect effects - “Feasibility depends on the political parties in office” |

Reduce incentives for commuting to work by car | 3.7 | + “it is a weird subsidy that should be removed” - those affected are likely to oppose - low political feasibility in Sweden |

Extension of product lifetime | 3.7* | + has strong public support + possible co-benefits in reducing material use and creating new business opportunities - hard to monitor and enforce bans on planned obsolescence - trade-off with energy-efficiency gains of new products, such as new cars, fridges, etc. |

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism | 3.7* | + safeguards EU industries and jobs + incentivises exporting countries to price carbon - potential trade conflicts and negative impacts on the economy of exporting countries |

Subsidies to increase demand for low emission products | 3.5 | + generally high feasibility and potential + removal of fossil subsidies a potentially effective measure - risk of subsidies benefitting affluent consumers and marginally better technologies |

Consumption taxes | 3.4 | + significant potential to reduce emissions - possible unequal distributive effects - low public acceptance (but possible to counteract) - strong opposition from producers |

*ranking from the first round | ||

Reduce Barriers to Policy Implementation

The expert comments pinpoint a wide range of possible barriers to policy implementation. In most cases, they give directions towards how these barriers could be overcome. The most significant barrier is simply a lack of effectiveness. Experts comment that certain proposed designs of a particular policy instruments risk having little to no effect. However, in most cases there are alternative “stronger” designs of the same policy which could be effective (for example a high tax on air travel), but risk suffering from lower acceptability. Perceived effectiveness is an important aspect of gaining public acceptance, as information on the effectiveness of an instrument can increase its acceptability (see section 5).

A common theme concerns the lack of public acceptance of certain policies, although such concerns vary considerably between individual experts. Informational measures that are viewed as weak instruments in isolation, are viewed as an important complement to increasing the acceptance of other policy approaches, and therefore imperative to include in broader policy packages.

Concerns are raised in relation to policies which risk disproportionately affecting low-income groups, or other groups such as rural population. This concern echoes the literature on public acceptability, which underlines perceptions of distributional fairness as key. Possible means of compensation and exemptions that would benefit certain groups are proposed. However, as emphasized at several instances in this report, compensatory policies cannot be evaluated in isolation. For example, in Sweden environmental taxes account for 4.4% of total tax revenues, Norway 4.6%, Iceland 4.6%, Finland 5.8%, and in Denmark 5.9% (OECD, no date), all slightly below the OECD average country and pinpointing that such taxes (environmental tax includes resource tax, energy tax, transport tax and pollution tax) play a marginal role in affecting general economic inequalities.

Importantly, the expert comments depart from the typical focus on public acceptance, instead noting the role of political and commercial resistance. Although there are plenty of examples of policies affecting consumer demand in place, targeting consumers is understood as politically sensitive among policymakers (Isenhour & Feng, 2016). Moreover, in several cases experts observed that particular commercial interests stand to lose if demand for their products is reduced. They are therefore likely to resist policies aimed at reducing consumer demand.

It should be noted that both the long and shortlist of high-ranking promising policies include both carrots and sticks. These can be combined in policy packages for increased acceptance and effectiveness. When developing policy packages, a general guideline would be to include:

- Policies that punish the currently worst alternatives.

- Policies that support the currently best alternatives. Care must be taken to make sure that people most impacted by punitive policies can benefit from supporting policies.

- Policies supporting more long-term sustainable solutions.

- Information campaigns and tools that support such policies.

This report provides many suggestions that can be used in such packages.