7. Results

Consumption-Oriented Policy Mapping

Mapping the Academic Literature

Our literature review found a growing body of academic literature (n=113) that addresses consumption-based greenhouse gas emissions and related policies in the Nordic context. Most articles focus on quantifying emissions and highlighting unsustainable consumption levels requiring policy interventions. The current literature lacks specific policy implementation discussions.

This literature review includes only articles discussing policy measures (n=16). None of these articles focus on policy comparisons or the evaluation of existing policies, though some introduce methodologies for assessing policy impacts. Policy recommendations vary and often stem from studies targeting specific areas like food, transport, or consumption of durable goods (e.g. Clarke et al., 2017; Heinonen et al., 2022; Kirikkaleli et al., 2023).

Several articles quantify potential GHG emission reductions from specific policies. Consumption-based accounting identifies emissions sources and policy intervention areas overlooked in territorial inventories, such as international transport and imported products (e.g. Clarke et al., 2017; Isenhour & Feng, 2016; Kirikkaleli et al., 2023). Schmidt et al. (2019) observe stable overall consumption-based emissions in Sweden from 1995 to 2014 but noted a shift towards embodied emissions in imports. They recommend policies targeting high-emission products or advocating for changes in production processes through international technology transfer (Schmidt et al., 2019). Since 2014, the consumption-based emissions have decreased in Sweden although slower than the territorial emissions as noted above.

The most common policy recommendation is to implement demand-oriented measures to complement other strategies. Studies propose using demand-oriented policies to raise awareness among consumers and policymakers (e.g. Dawkins et al., 2019; Heinonen et al., 2022), but warn against overemphasizing consumer responsibility (Dawkins et al., 2023). Isenhour & Feng (2016) highlight that an extensive focus on consumption-based GHG emissions in Sweden has had marginal policy implications, noting political sensitivity and resistance to demand-oriented measures at higher policy-making levels.

Wood et al. (2018) develop a framework to estimate GHG reduction potential for various consumption-based policies, using Multi-Regional Input-Output tables. Westin et al. (2019) propose a method to evaluate the impact of planned actions on consumption-based environmental footprints. Heinonen et al. (2022) suggest considering GHG intensity per monetary unit to avoid rebound effects from monetary savings spent on carbon-intensive categories.

Few articles discuss economic impact, feasibility, or political and societal acceptance. Schmidt et al. (2019) argue that consumption-reducing policies may disproportionately impact economically vulnerable individuals. Dawkins et al. (2023) found that 40% of Swedish households face risks from food price hikes and transportation costs, while high-income households are responsible for most air travel emissions. They call for transitional assistance policies targeting high-emission demographics and supporting vulnerable groups based on measures of environmental effectiveness, social equity, and political feasibility.

Ottelin et al. (2018) find that Nordic welfare states have more equal carbon footprints among their citizens compared to other countries, but also contribute to high carbon and material footprints. They suggest green investments supported by carbon pricing, although they acknowledge regressive effects on low-income groups. Returns from carbon taxation could fund low-carbon infrastructure and welfare services, or education and green investments to mitigate these impacts (Ergon et al., forthcoming; Ottelin et al., 2018).

Mapping Non-Academic Literature

In addition to academic articles, non-academic literature was also mapped as part of this research. We used the Nordic Council of Ministers periodical report “Use of Economic Instruments in Nordic Environmental Policy” as a starting point to map policy literature. Since the report collects information on environmental policy in all Nordic countries, it was most effective to begin with the latest report, covering the years 2018–2021 (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2023b). We also examined national publications concerning all studied countries. These publications include national communications, and biennial reports to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, several years), as well as reports related to the development of emission and policies to reduce emissions published by national environmental protection agencies and statistical agencies. We further examined reports from Mistra Sustainable Consumption (see Table 4).

Policy Instruments Longlist

We compile all identified policies in a longlist. Similar policy proposals have been merged into generic categories. Specific policy proposals, such as exact designs and levels of proposed carbon tax, have not been included as specific policy measures. Rather, they have been included in the policy measure category. This has allowed us to compile, and briefly describe, approximately one hundred policy proposals. An absolute majority of the identified policies are consumption-oriented (i.e., directly targeting consumer behaviour). In some cases we have added measures which are not explicitly consumption-oriented, but which have been characterised in the literature as key to reducing consumption-based emissions.

We have relied extensively on previous mappings (see Table 4). The Carbon-Cap project is an important source for our policy measure descriptions (see Grubb et al., 2020). To save space the longlist presented here does not include references. For the full record, we refer to the online appendix which is available in the form of an Excel file. Our hope is that making our full mapping available and editable will support future research and policy analysis.

Table 6. The longlist: Consumption-oriented policies in the Nordic countries (in use today, previously used, or discussed)

Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

Product labels | Information instruments | Requirement to provide information on product labels on emissions of greenhouse gases and other air pollutants. |

Negative labelling | (inf) | Food products with negative labelling that signals if there is an environmental or health problem with the product |

Positive labelling | (inf) | Ecolabelling or certification can reduce the environmental impact in two ways; by the producers changing their production in order to be eco-labelled and by the labelling changing the consumers' choices. |

Environmental declaration | (inf) | Forms of environmental declaration include energy declaration on the energy performance of houses, but also graded labelling (e.g., traffic-light colours + letters) which combines negative and positive labelling |

Information campaign | (inf) | Information campaigns that inform consumers on products and behaviour that cause high emissions of greenhouse gases and other air pollutants. |

Promotions for vacationers in the home country | (inf) | Campaigns to increase the status of vacationers in the home country, such as cottage vacations, active vacations or learning vacations such as summer courses. |

Consumer guides and dietary advice | (inf) | Mandatory information available to consumers on environmental and health effects of food items and diets. |

Environmental education | (inf) | Develop pedagogical materials that can help teachers increase students' knowledge about food and its environmental impact. |

Energy and climate advice | (inf) | Energy and climate advice is a free service that helps consumers become more energy-smart and reduce their energy use. Energy and climate advisors help the consumer with questions about heating, energy efficiency, transport, energy costs and much more. |

The hourly measurement reform | (inf) | The purpose of the hourly metering reform is to give electricity users incentives to change their consumption pattern and thus shift part of their electricity consumption from times of the day when the electricity price is higher to times when the price is lower. |

Energy labelling | (inf) | Energy labelling shows how energy-demanding a product is. The energy class is shown on a scale from A to G, where A is the best, and with arrows from green to red. |

Product location at point of sale | (inf) | Low carbon products are given preferential placement at retail stores, internet sites, etc |

Rankings and award campaigns | (inf) | Product manufacturers and/or sellers are given publicly celebrated awards for low carbon performance through government, trade or third-party organisations |

Approved technology lists | (inf) | List of specific low carbon technologies that are given preferential procurement |

Graduated tax on advertising | (inf) | Size of VAT on advertising increases with increasing carbon implications, within each class of products. |

Advertising regulation | Regulatory & Administrative Instruments | Advertisement restrictions regarding where, when or how products or services with high emission intensities can be marketed. |

Business emission agreements/allowances | (reg&admin) | Businesses are required to acquire allowances for Scope 1 & 2 (at least) emissions, generally with trading |

Requirements for improved sustainability | (reg&admin) | Successively increased demands are placed on food sold in the grocery store to be sustainable, for example through targets/requirements relating to climate, biological diversity, health and social aspects. |

Public procurement | (reg&admin) | Requirements that public agencies must choose low or zero emission products or services when available. |

Reduce emissions from public employee business trips | (reg&admin) | Reduce the number of long-distance business trips by public employees in the state, regions and municipalities. For example, by setting goals and guidelines for reduced business flying, technology for remote meetings and individual bonuses for reduced flying. |

Linking public procurement to national climate change acts | (reg&admin) | Legal requirements to consider national climate goals in all public procurement |

Consumer carbon budget/personal carbon allowances | (reg&admin) | Consumers are provided an annual carbon budget and cannot exceed this, perhaps (but not necessarily) with allowance for trading; note that this budget might be either for individual categories, or might be specified as an aggregate emissions and consumers can choose how to allocate the budget across categories |

Flight rights | (reg&admin) | Consumption is regulated by allocating emissions rights to consumers, in this case for flights, in order to reduce emissions from flying. |

Consumption rights for meat | (reg&admin) | Regulate meat consumption by distributing consumption rights for meat to the consumer, in this way the total volume of meat sold is regulated, but the consumer can choose to use his consumption right or to sell it on. |

Regulatory standards | (reg&admin) | Regulation of emissions from products. |

Reduction obligation for aviation fuels | (reg&admin) | Blending of biofuel into jet fuel, with timed quotas for the proportion of biofuel that must be mixed in time. The reduction option may also include the blending of synthetic aviation fuels and be broadened to include increased efficiency as a requirement. |

Sector trade body standards | (reg&admin) | Voluntary product performance standards set by trade organisations and to be followed by all outlets in that trade |

Licenses | (reg&admin) | License is required either to sell or purchase high carbon products |

Supply chain procurement requirements | (reg&admin) | Consumer-facing outlets establish embodied carbon requirements on intermediate producers, with refusal to procure unless the requirements are met |

Voluntary agreements by trade organisations | (reg&admin) | Trade organisations adopt voluntary commitments to reducing embodied and/or usage carbon of products offered to consumers |

Required recycling | (reg&admin) | A ban on disposal (including landfilling and incineration) of products and materials that can be reused or recycled is introduced. |

Sale of leftover food | (reg&admin) | Offer a range of things based on leftover food from restaurants or commercial kitchens. |

Extended producer responsibility | (reg&admin) | Producers have responsibility for collecting and recycling products at end of use. |

Product ban | (reg&admin) | Products are banned based on criteria of embodied and/or usage carbon |

Prohibition of certain vehicles in urban zones | (reg&admin) | An environmental zone limits the type of vehicle that may be driven within a specific area. |

Ban on short flights | (reg&admin) | A short-haul flight ban is a prohibition imposed by governments on airlines to establish flight connections over short distances. |

Shop product choice | (reg&admin) | Point of sale operators voluntarily restrict products to lower embodied and/or usage products |

Waste targets, requirements and/or prices | (reg&admin) | Product recycling is motivated through waste policies that place either a requirement for, or a price on waste generation |

Deposits on purchased goods | (reg&admin) | Deposits are initiated to enhance recycling of goods to reduce raw materials requirements |

Repair checks and repair funds | (reg&admin) | Consumers get access to repair vouchers when purchasing certain product groups which can be redeemed to reduce the price of repairs or upgrades to the product. |

Minimum price limits | (reg&admin) | Very low prices are banned to remove from markets products that have less incorporation of externalities |

Limits on percentage ownership or use | (reg&admin) | Nations or municipalities restrict the number of a given product (such as cars) that can be purchased and/or owned (note: some nations such as Singapore have applied this instrument for vehicles, but none have applied it in other products/sectors) |

Extension of product lifetime | (reg&admin) | Enhancement of product lifetime, including removal of planned obsolescence, and ban on disposal of unsold and functional products. |

Ban on disposal of unused products | (reg&admin) | Companies are prohibited from disposing of unsold and functional products and are required to instead resell, donate or reuse products. |

Information on service life and repairability | (reg&admin) | Introduce requirements for labelling with expected lifespan of goods within durable goods, linked to a lifespan guarantee. One example is the EU initiative for Digital Product Passport |

Minimum requirements for repairability | (reg&admin) | The possibility of repairing many goods is very limited or non-existent today. Minimum repairability requirements would require manufacturers to design products to be taken apart and repaired. The minimum requirement can also be supplemented with a requirement for the producers to inform the consumer about how long they will provide spare parts. |

Extended right of complaint | (reg&admin) | Extend the statutory period for right of complaint, which would give companies an incentive to sell goods with better quality |

EU Eco-design for Sustainable Products Regulation | (reg&admin) | The proposal establishes a framework to set eco-design requirements for specific product groups to significantly improve their circularity, energy performance and other environmental sustainability aspects. It will enable the setting of performance and information requirements for almost all categories of physical goods placed on the EU market (with some notable exceptions, such as food. |

Carbon tax | Economic instruments | The carbon tax is levied on most fossil fuels in proportion to their carbon content, this could be expanded to include also e.g. CO2 from fuels used for fishing and agriculture. |

Fuel and vehicle taxes | (econ) | Key policy instrument for reducing consumption-based emissions but is extensively covered in previous literature. |

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism | (econ) | Importers who bring certain types of goods (CBAM goods) into the EU from third countries are obliged from 1 January 2026 to declare embedded emissions of greenhouse gases in the goods and to purchase certificates corresponding to the embedded emissions. This policy measure could also be used for other types of goods. |

Consumption taxes | (econ) | Many countries have consumption taxes based on emissions of greenhouse gases on petrol and diesel. This could be expanded to other product categories. |

Excise duties | (econ) | Introduce point taxes to reduce or redirect consumption from environmentally harmful or unhealthy goods and services. |

Flight tax | (econ) | Tax on air travel tickets |

Frequent flyer tax | (econ) | Progressive tax on air travel, with an increasing tax the more you fly. |

Taxes on unsustainable food | (econ) | Taxes on meat and dairy products so that the price for the consumer is increased to reduce the consumption of these and thus also the climate impact. |

Bonus-malus systems | (econ) | A bonus-malus is a system where products with relatively low emissions of carbon dioxide are rewarded at the time of purchase with a bonus, while products with relatively high emissions of carbon dioxide are charged with a higher tax. |

Bonus-malus system for flights and trains | (econ) | Introduce a system with an integrated air-train tax, where increased taxes (malus) on air travel are used to direct subsidies (bonuses) to train travel. Such a system can even out the price difference to flights and increase demand for train travel. |

Bonus-Malus system for home decoration | (econ) | Products with a low environmental impact and a long lifespan are stimulated by a lower fee, while goods with a higher environmental impact and a shorter lifespan are charged a higher fee (for example through VAT differentiation). |

Cash compensatory measures | (econ) | Environmental taxes risks being regressive (i.e. effecting people on low income more). Targeted, compensatory measures have been proposed to address this. |

Fee & dividend for climate-harming consumption | (econ) | Environmental taxes risk being regressive (i.e. affecting people on low-income more). Targeted, compensatory measures have been proposed to address this. Policy packages can combine e.g. consumption taxes with a refund targeted specifically towards low-income households. |

Subsidy | (econ) | Subsidies directed at purchases of low emission products which have the potential to grow and push out technologies or practices with higher emissions. Subsidies can be targeted towards novel technologies and products as well as established ones. |

VAT differentiation | (econ) | Regulate the VAT so that it is, for example, lower on services and used goods, which would benefit, for example, repairs over new purchases. |

Subsidize repair services | (econ) | Subsidize repair services to increase the profitability of these companies/organizations and, by extension, speed development. Can happen e.g. through reduced tax or VAT. |

Investment subsidies | (econ) | For instance, investment subsidies which reduces demand for high carbon products, for instance subsidies for electric vehicles or home batteries for solar power |

Industry subsidies | (econ) | Key policy instrument but outside the explicit scope of this mapping |

Remove climate-damaging subsidies for aviation | (econ) | For example, municipalities and regions that currently support, or own local airports can remove subsidies and deny new construction or expansion of runways. |

Abolish animal subsidies | (econ) | Abolish subsidies for animal consumption, such as the "school milk allowance". |

Subsidies on sustainable food | (econ) | Subsidize products and thereby lower the price for the consumer to get a consumer to choose a product with less climate impact than one with a higher impact. |

Tax deductions for sustainable services/products | (econ) | Tax deductions can for instance, be given to companies/organisations which work with upcycling products |

Subsidize second-hand sales | (econ) | Subsidize second-hand sales to increase the profitability of these companies/organizations and, by extension, speed up development (1). Can, for example, be done through reduced tax or VAT, or through forms of municipal support in the form of financing premises for second-hand sales (2). |

Energy efficiency | (econ) | Measures directed at lowering electricity or other power demand from private households* |

Tax reductions for home instalation of green technology | (econ) | * |

Support for certain environmentally-enhancing installations in single-family houses | (econ) | * |

Support conversion from oil heating in residential buildings | (econ) | * |

Investment support solar cells | (econ) | * |

Product user fees | (econ) | A fee is attached at point of sale based on carbon associated with subsequent use |

Refund mechanism | (econ) | Part of the price of purchase is refunded based on the product re-entering the recycling stream |

Preferential finance terms | (econ) | finance terms on loans – including credit cards – tied to carbon implications of product choice within a given category of goods. |

Finance policy | (econ) | Key policy instrument but outside the explicit scope of this mapping |

EUs sustainable finance taxonomy | (econ) | Key policy instrument but outside the explicit scope of this mapping |

Enabling recycling | (econ) | Facilitate for consumers to re-cycle products and materials at end of use. |

Enabling product sharing | (econ) | Creation of the infrastructure to enhance the ability of consumers to share products rather than purchase individual items. |

Spaces for sharing | (reg&admin) | Requirement that developers set aside space for the sharing economy |

Mandatory metering | (Enabling) | Requirement of metering for at least heat and electricity in buildings, and potentially for automobile use |

Infrastructure improvements | (Enabling) | Key policy instrument but outside the explicit scope of this mapping |

R&D and innovation policy | (econ) | Key policy instrument but outside the explicit scope of this mapping |

Work time reduction | Employers and other organizations can choose to facilitate sustainable lifestyles by offering the opportunity to reduce working hours (with a corresponding reduction in wages). | |

Targets and accounting of consumption-based emissions | (reg&admin) | Set targets for consumption-based emissions where emissions outside the country's borders are also included. |

Climate calculations for consumers | Tools that calculate individual climate impacts from transport, housing, consumption and food and provide inspiration for how you can live more sustainably. | |

Consumption-based Paris-compliant 1.5* carbon budgets as a climate policy framework. Calculated for the European Union | ||

International cooperation | Key policy instrument but outside the explicit scope of this mapping. High-income countries can direct investment and technology transfer to developing countries for their decarbonization | |

The Green Climate Fund | Key policy instrument but outside the explicit scope of this mapping. The UN Green Climate Fund is currently the world's largest multilateral fund to help developing countries finance climate mitigation. | |

Tax free shopping | Enabling increased consumption | Norway Customs Regulations. Tax free - possibility to bring in goods duty free for personal use (encourages flying rather than the opposite) |

Conditioning tax deduction for home repair | Tax deductions can be made for costs for home-repair if the work increases energy efficiency or reduces overall use of resources and materials. | |

Reduce incentives for commuting to work by car | Tax deductions for expenses from commuting to work should be neutral in relation to way of transport. | |

Policy Delphi

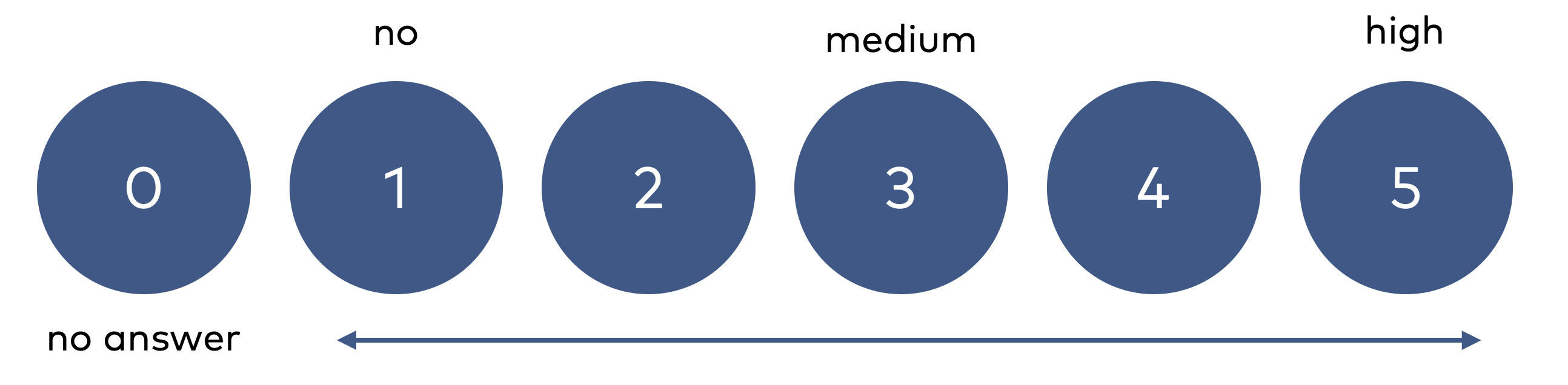

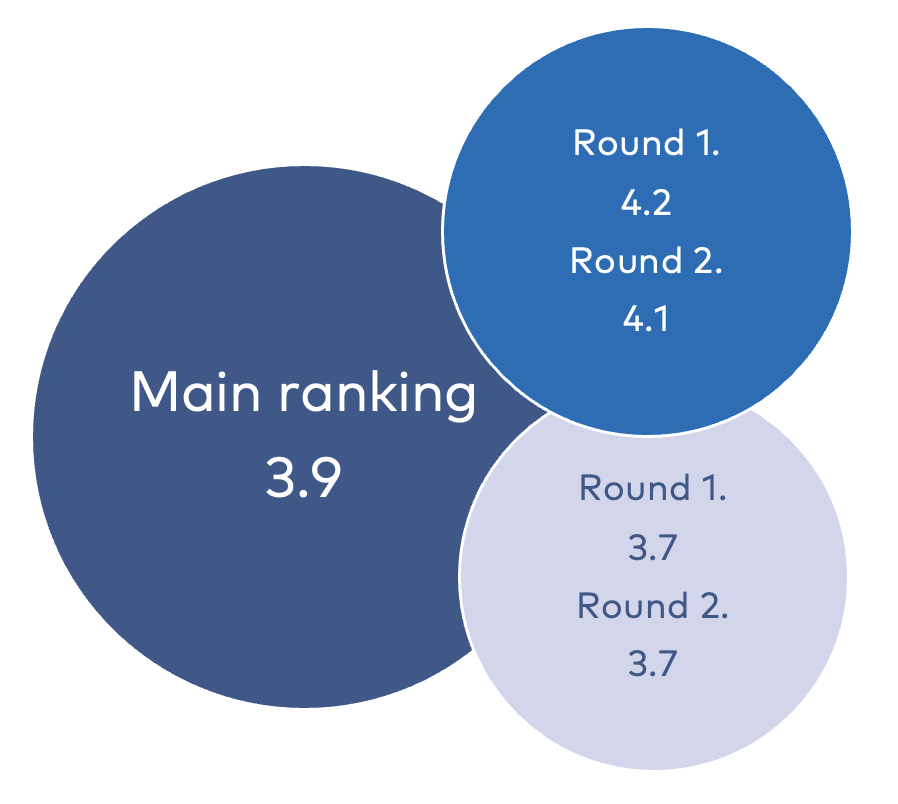

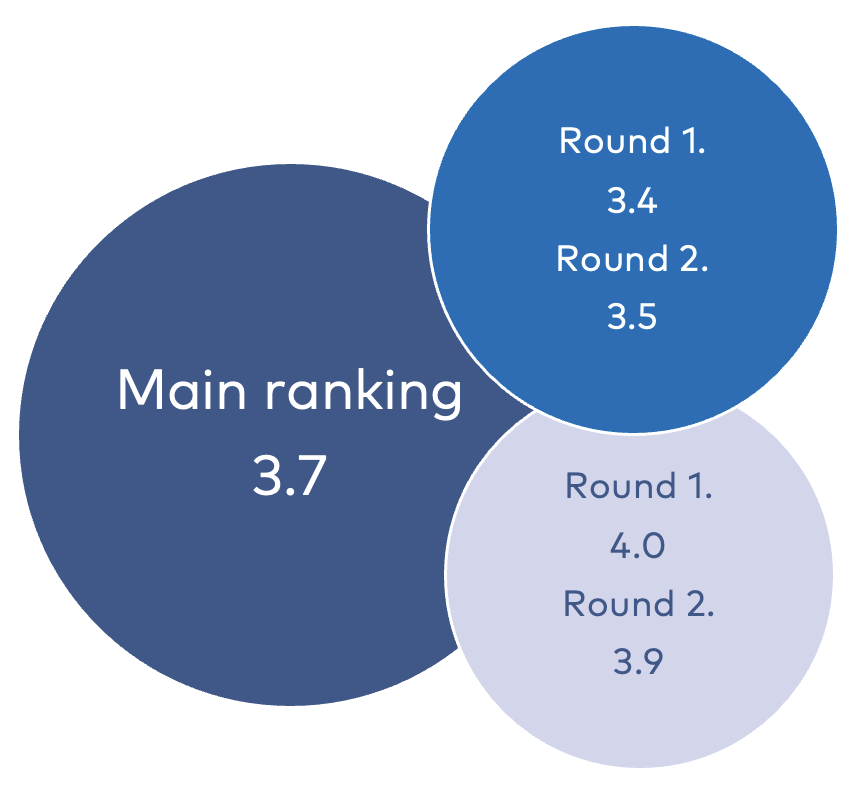

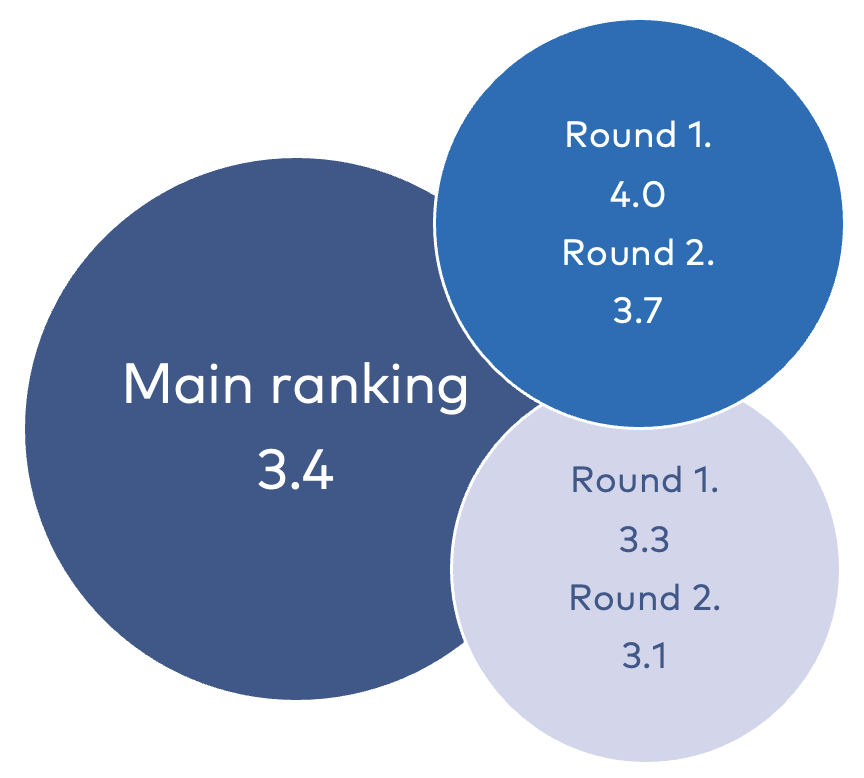

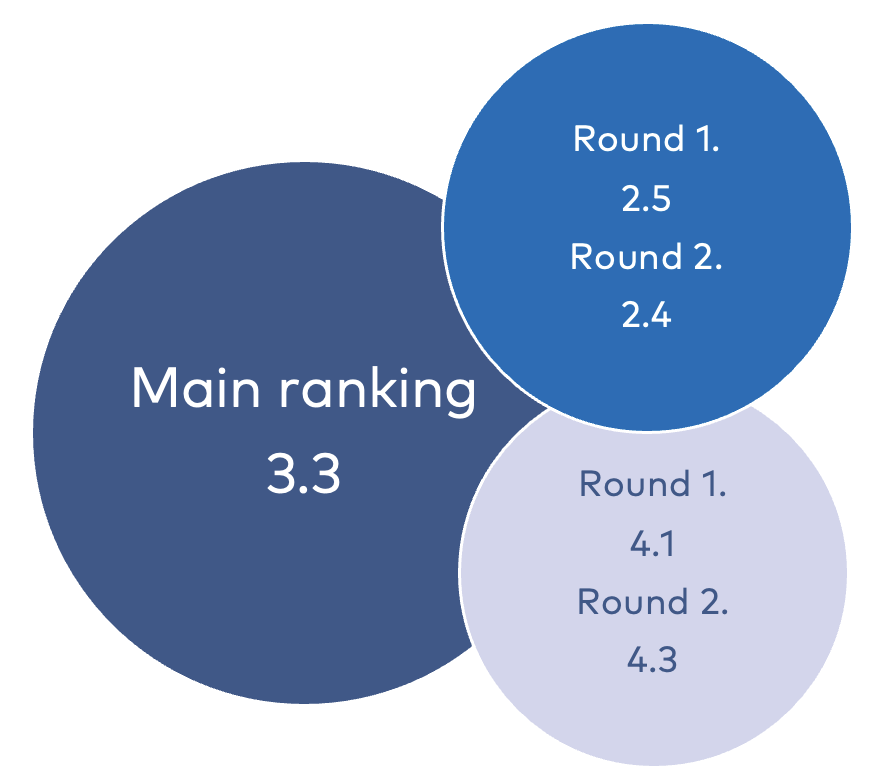

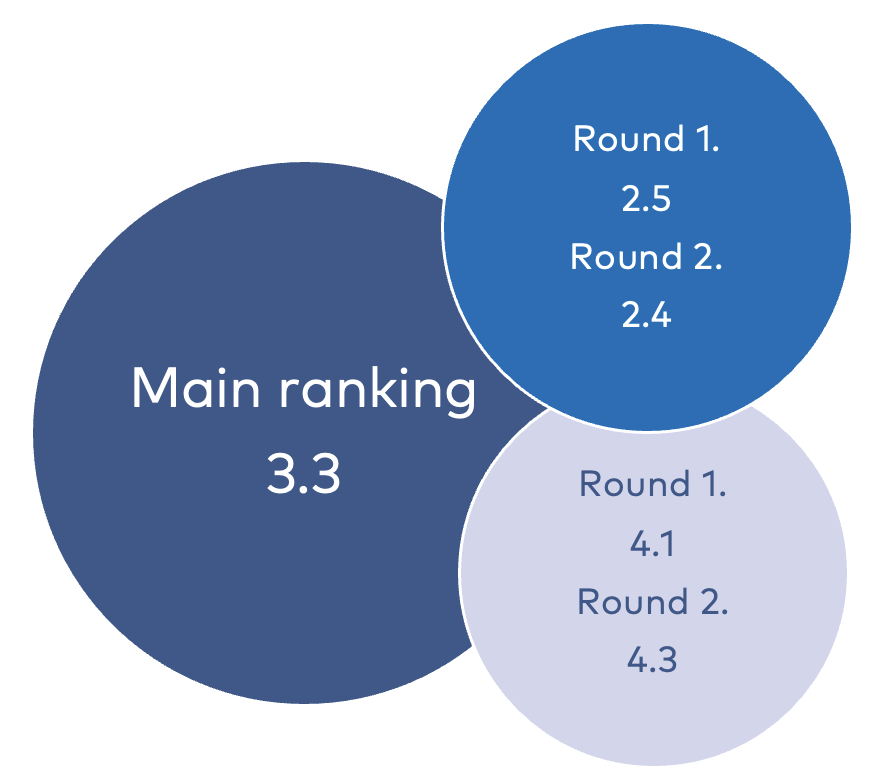

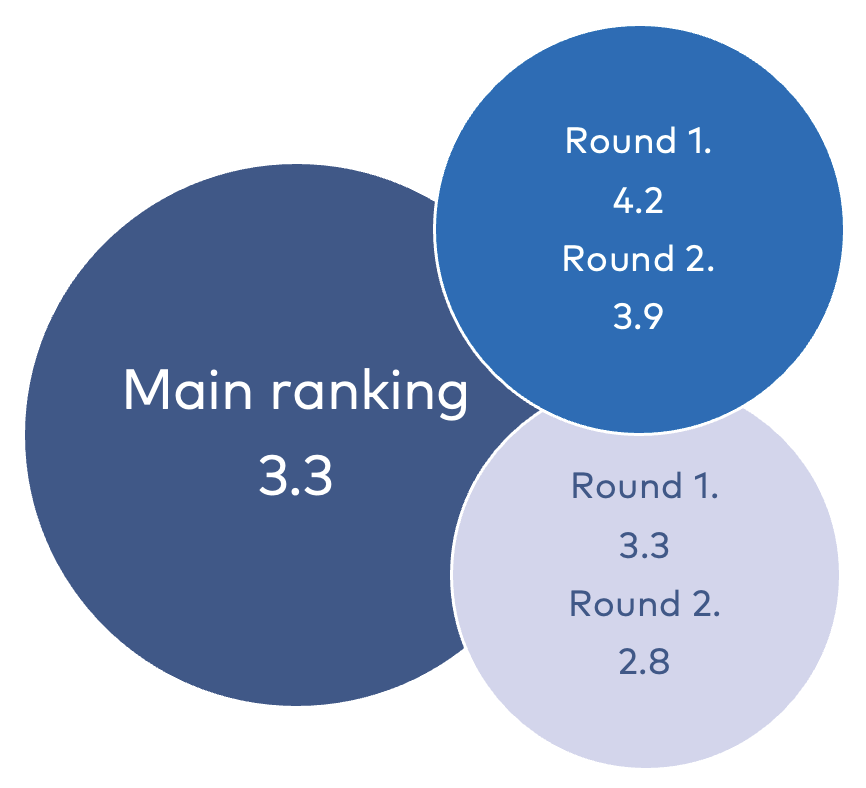

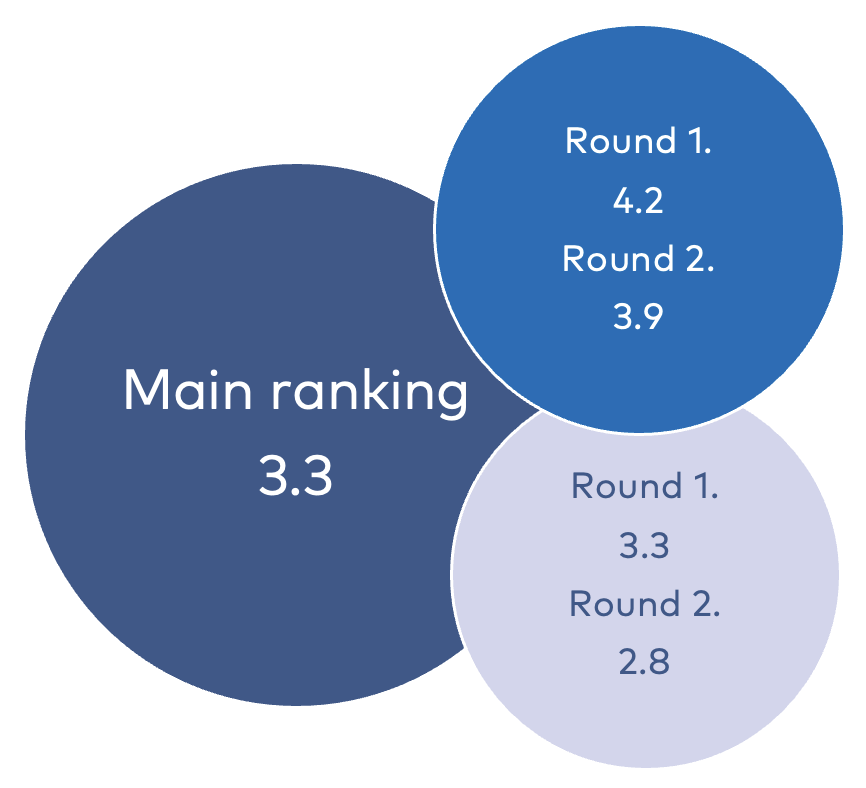

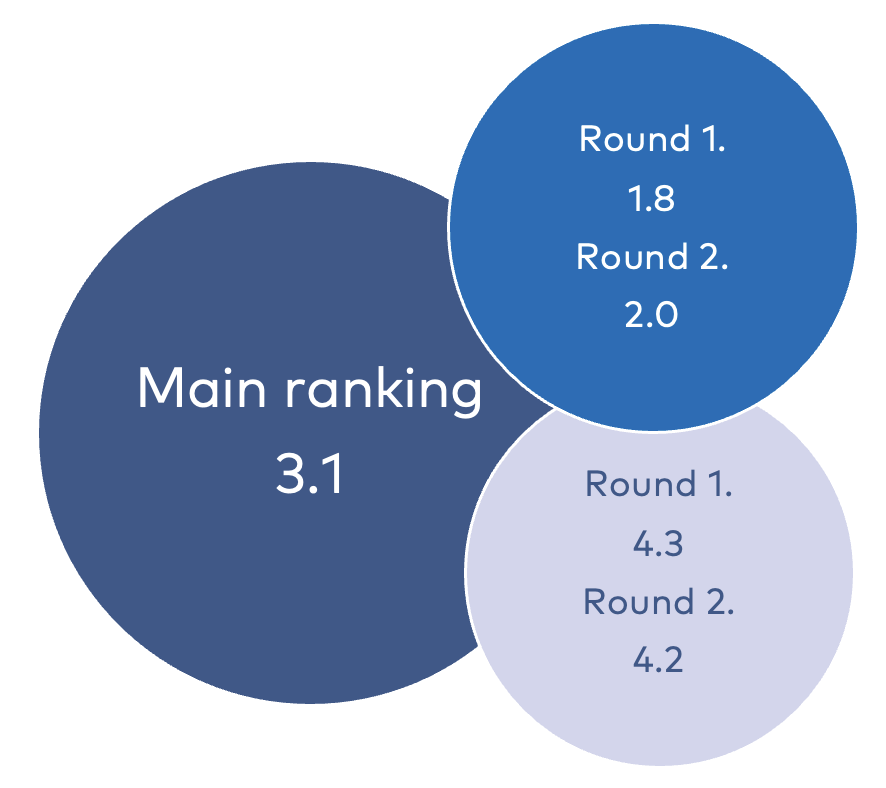

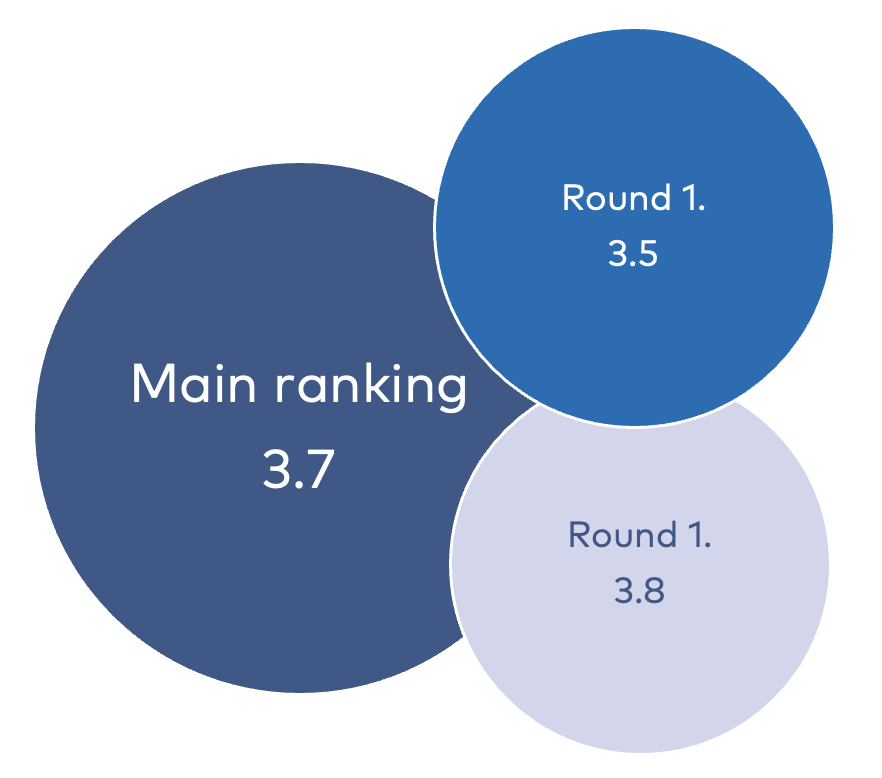

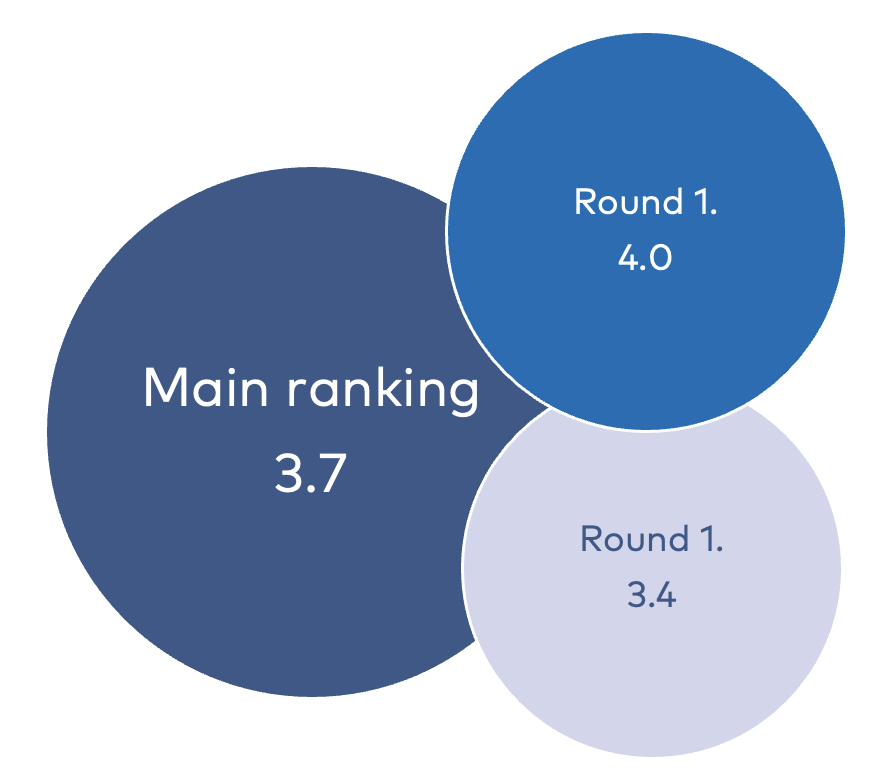

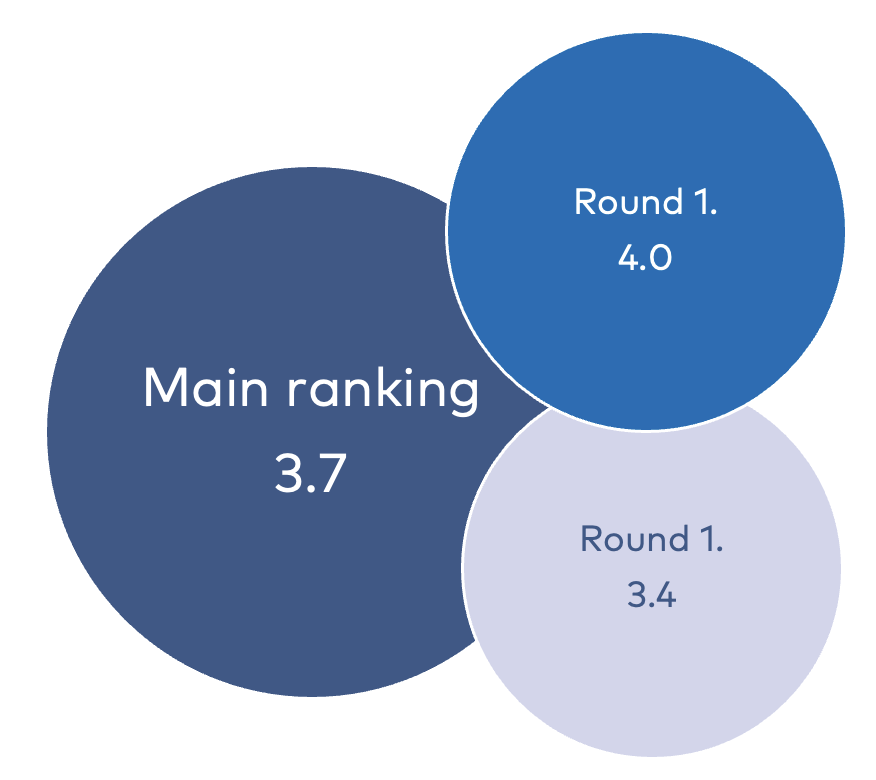

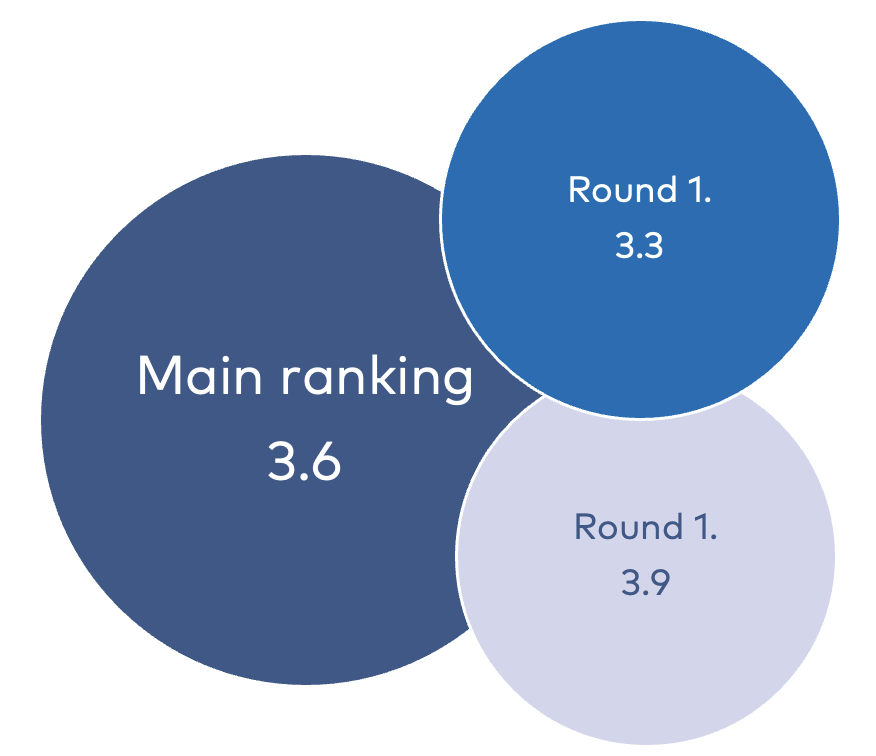

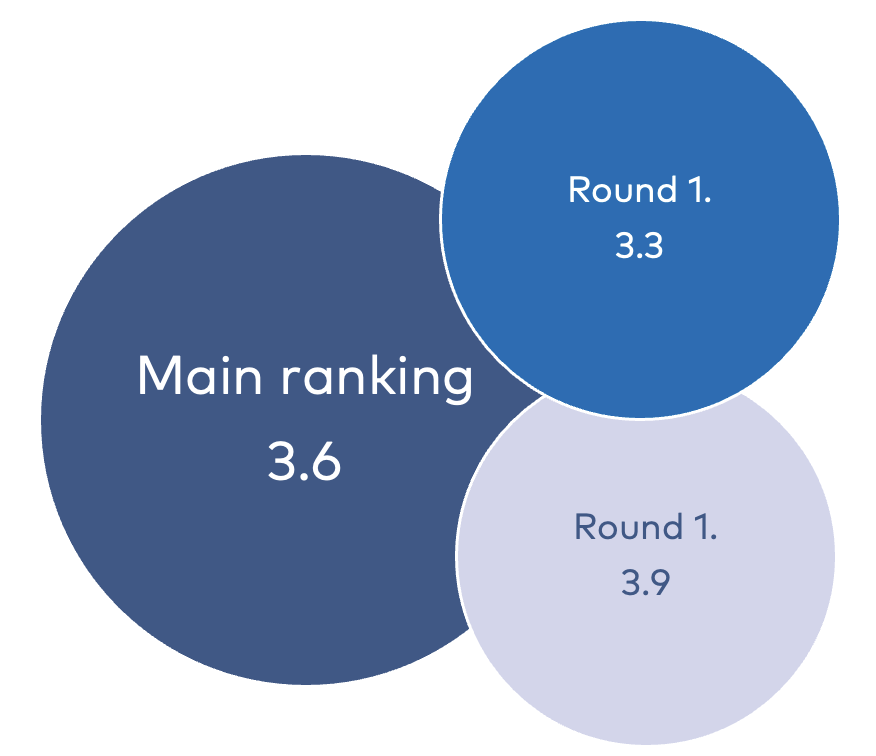

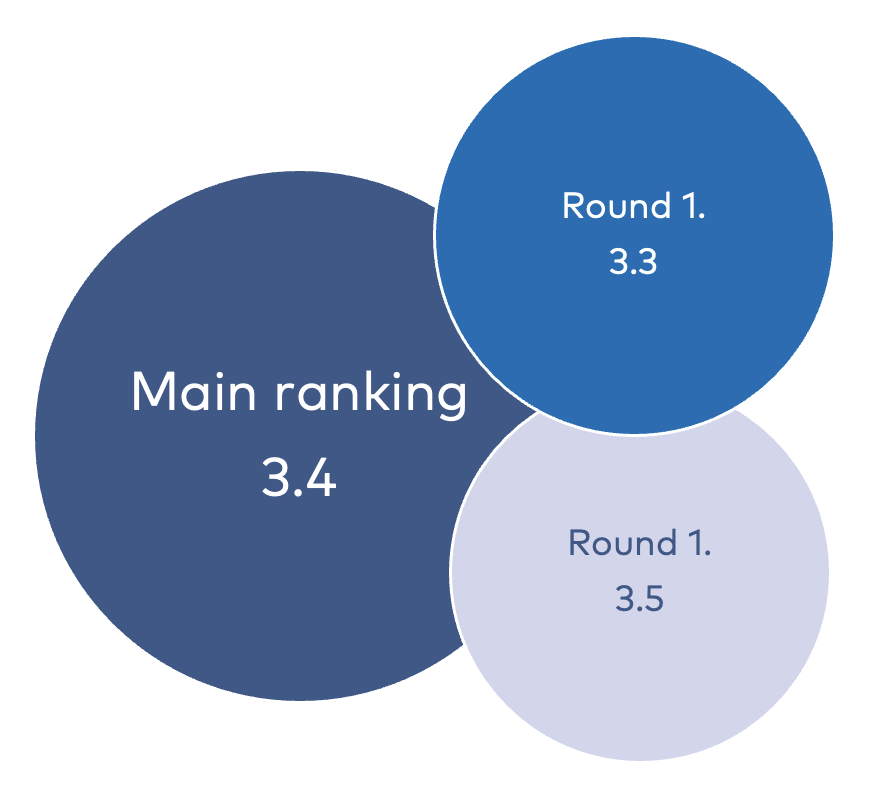

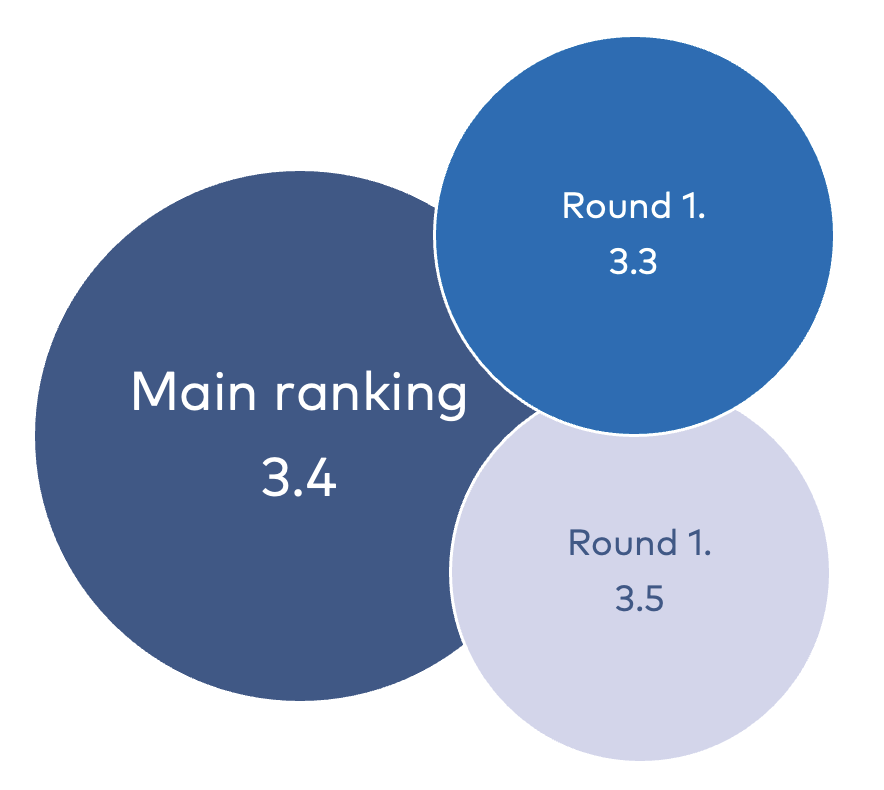

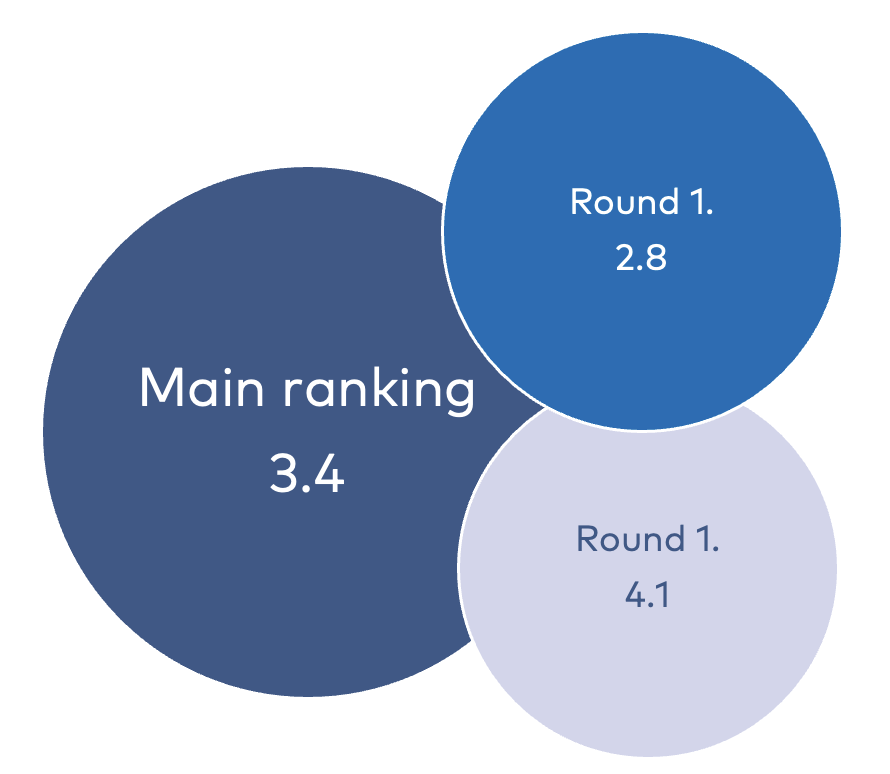

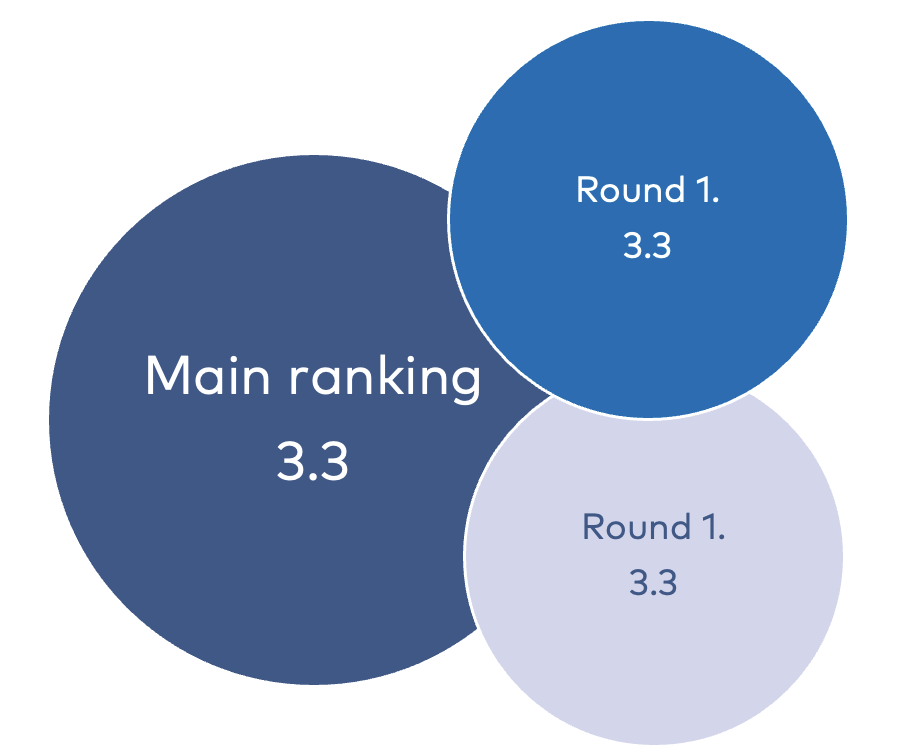

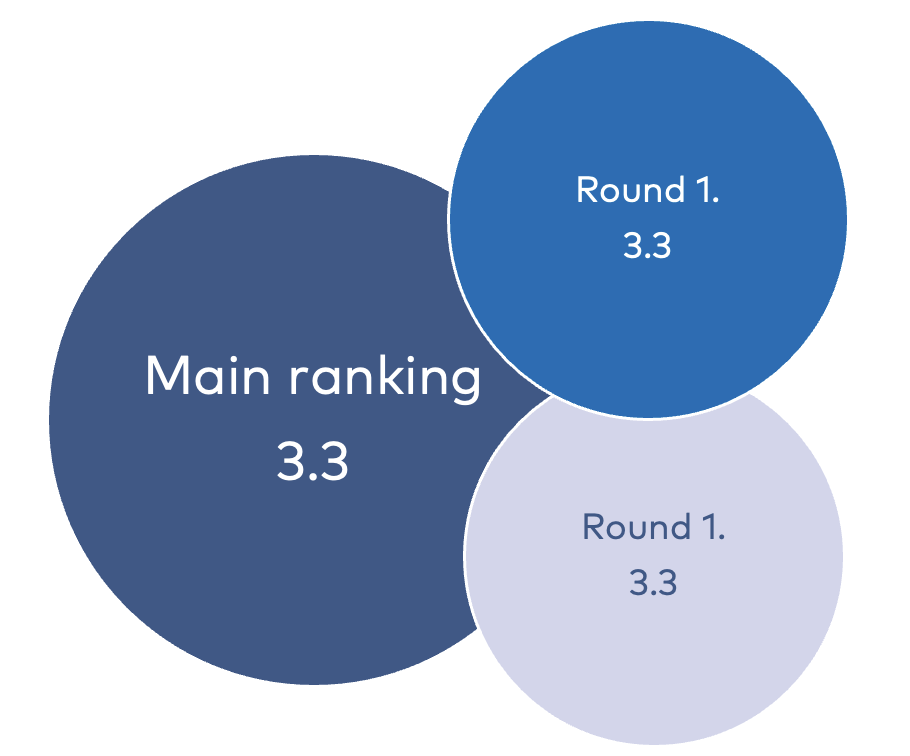

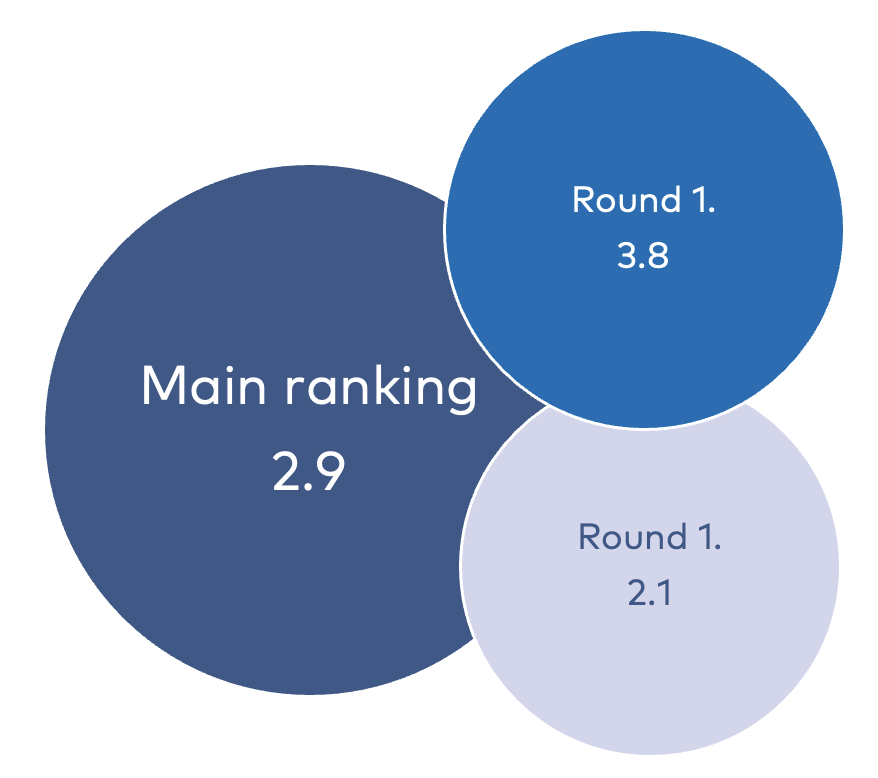

The Policy Delphi was conducted in two rounds. In round 1, the Nordic expert panel was asked to rank each policy according to their potential to reduce emissions, as well as their political feasibility (i.e. the likelihood for a policy to turn from idea into applied politics). Rankings were made 1–5, where 5 indicates a large potential to reduce emissions/high feasibility (see figures 11 and 12).

Figure 11. Rankings 1–5, 0 indicates missing values.

Figure 12. Rankings are presented in means for “potential to reduce emissions”, “feasibility” and combined scores of both.

Figure 12. Rankings are presented in means for “potential to reduce emissions”, “feasibility” and combined scores of both.

Round 2.

The selection of policies for the second round was based on high rankings regarding potential to reduce emissions and feasibility. For strategic reasons, the selection covered policies from different categories and policy instruments that are most relevant at the national level. Consideration was also given to the comments from round one, where participants observed that some listed policies were very similar.

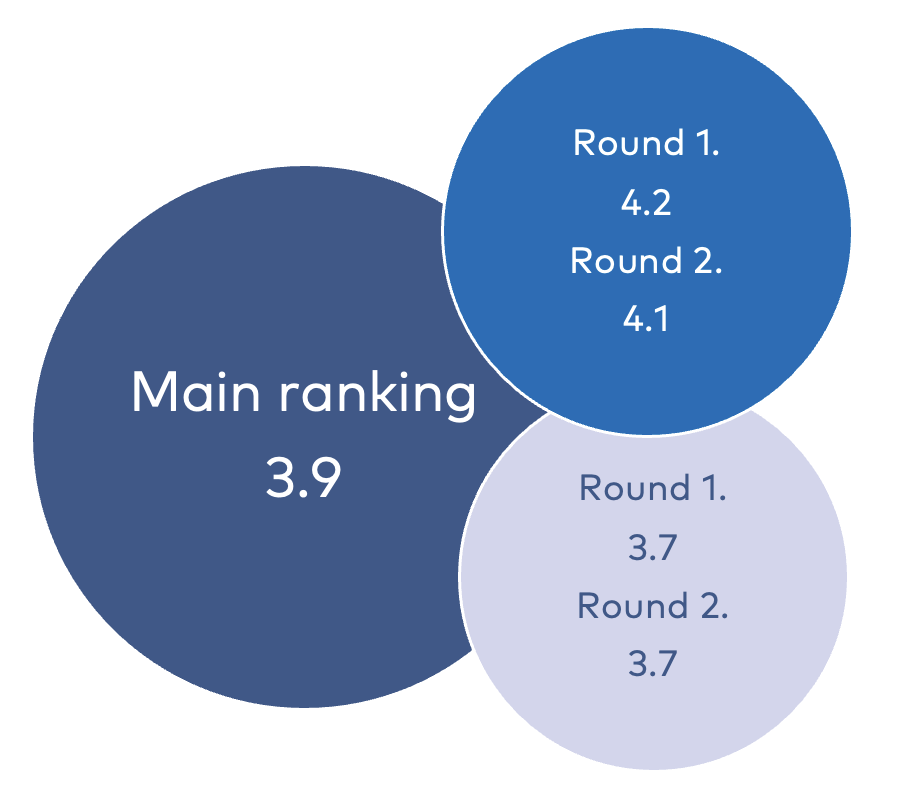

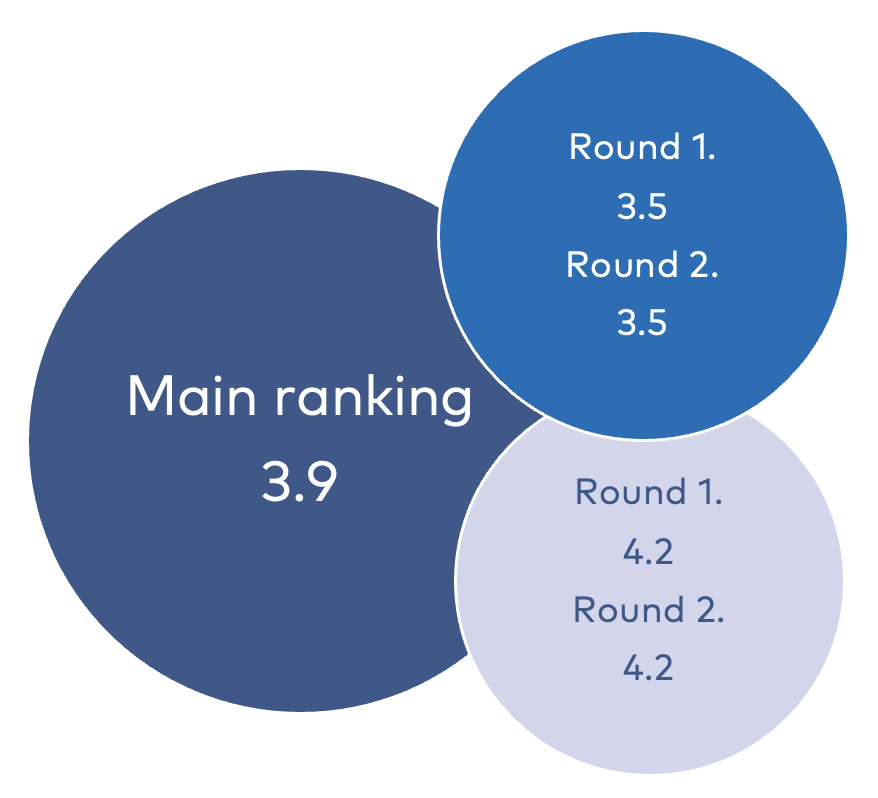

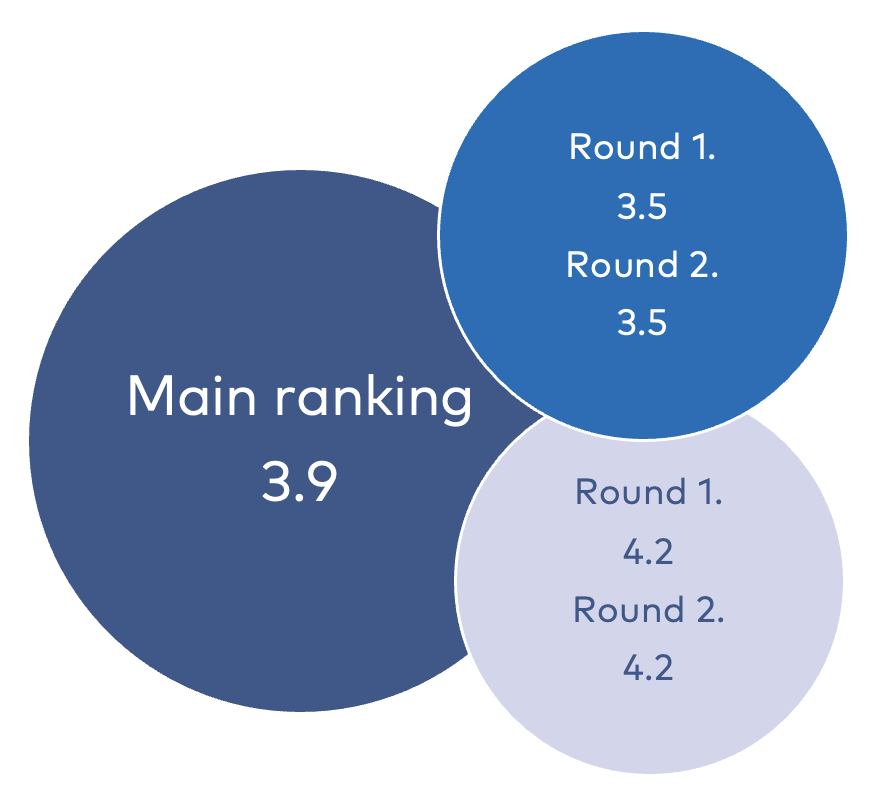

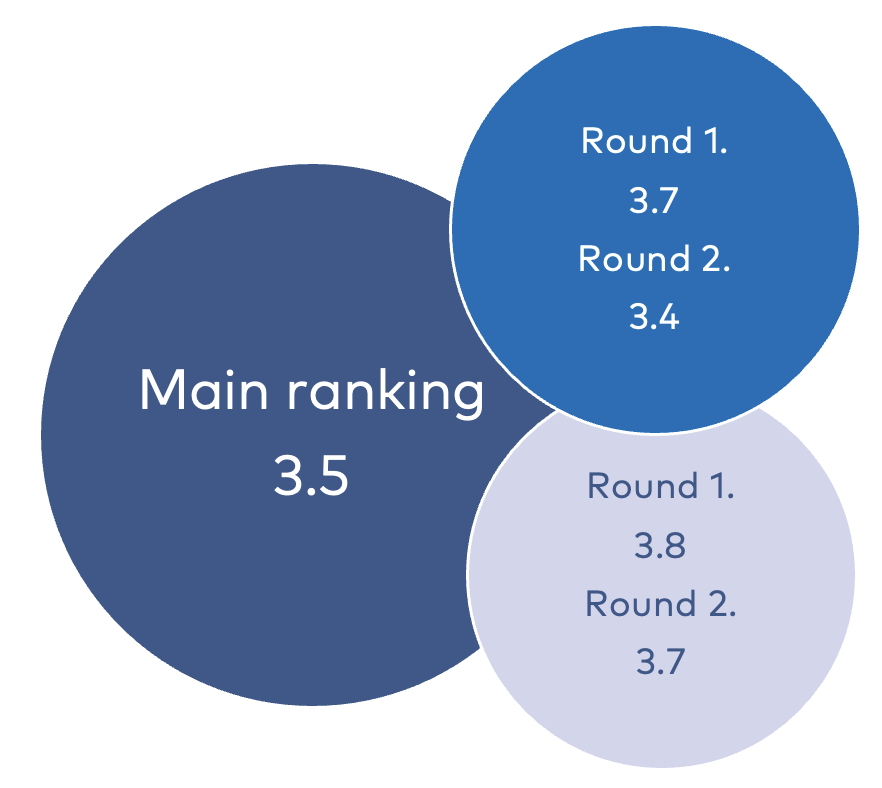

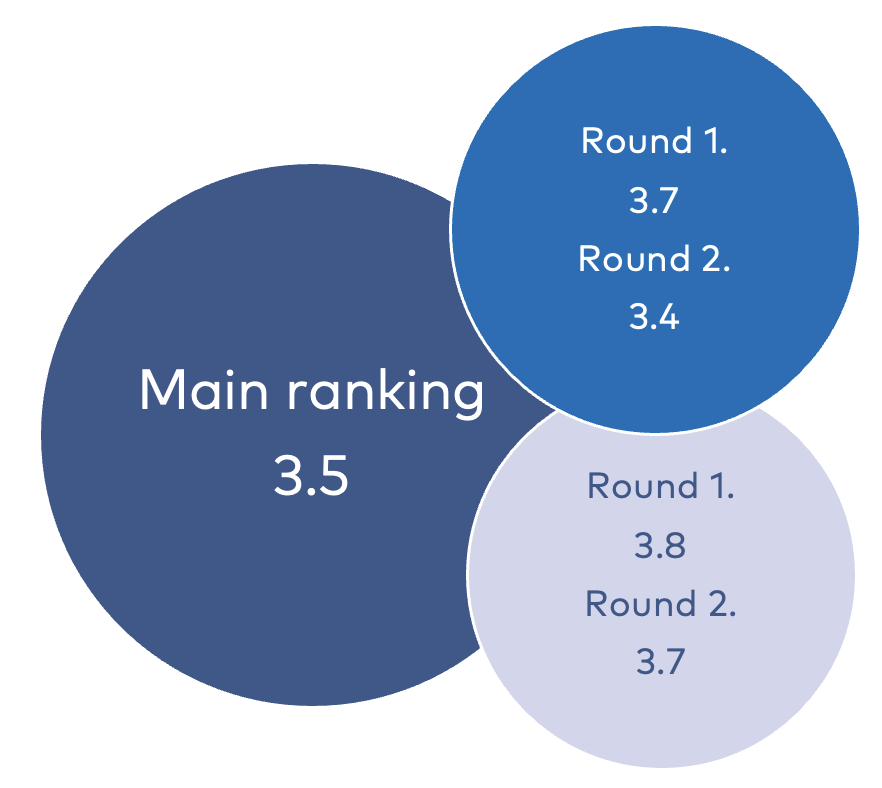

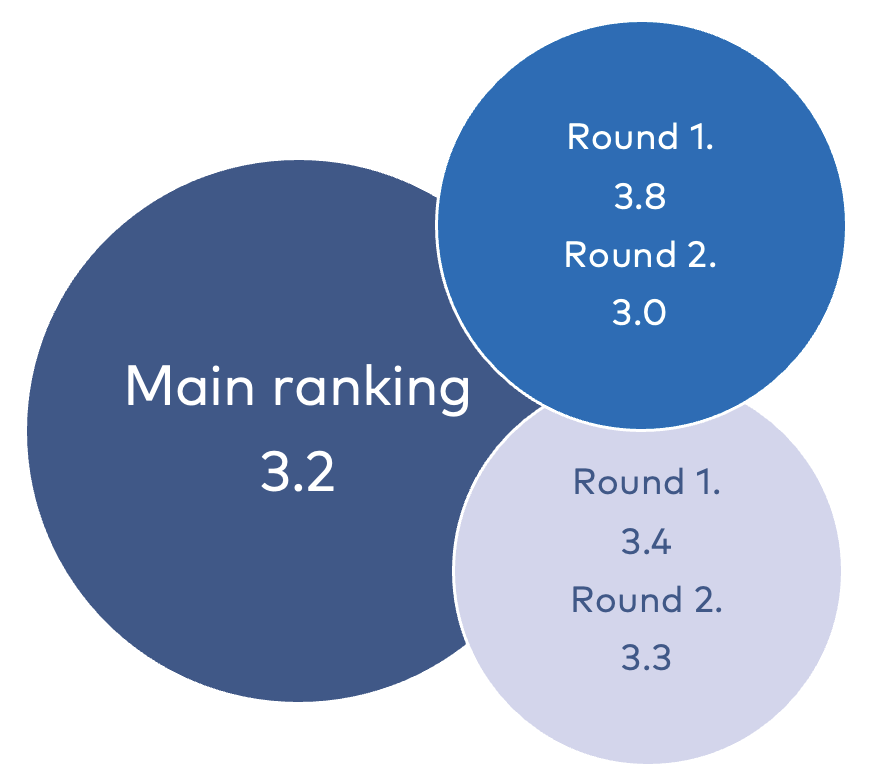

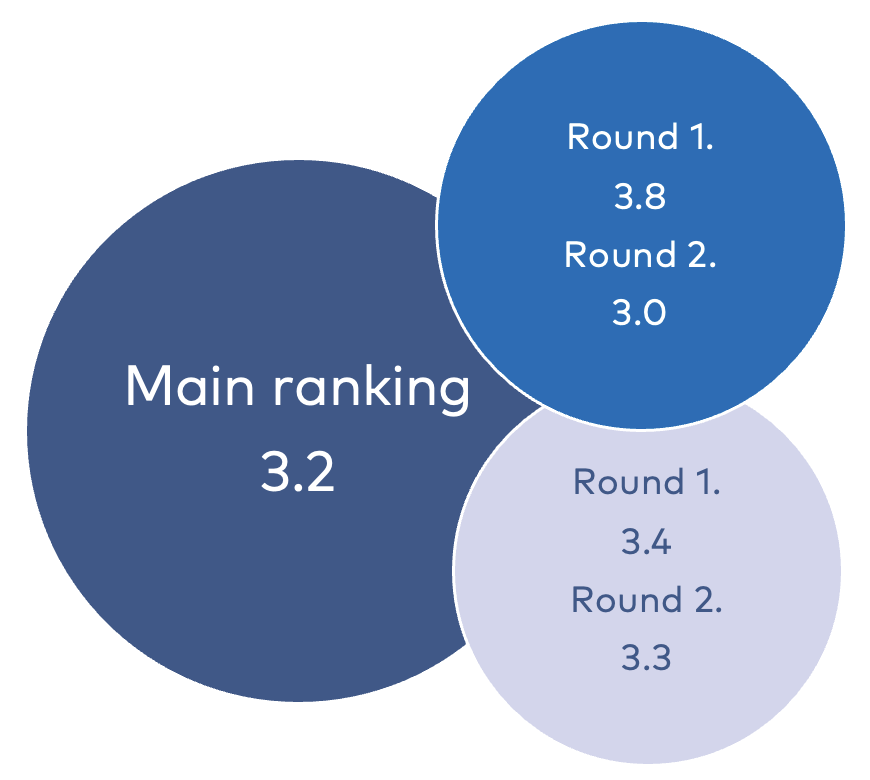

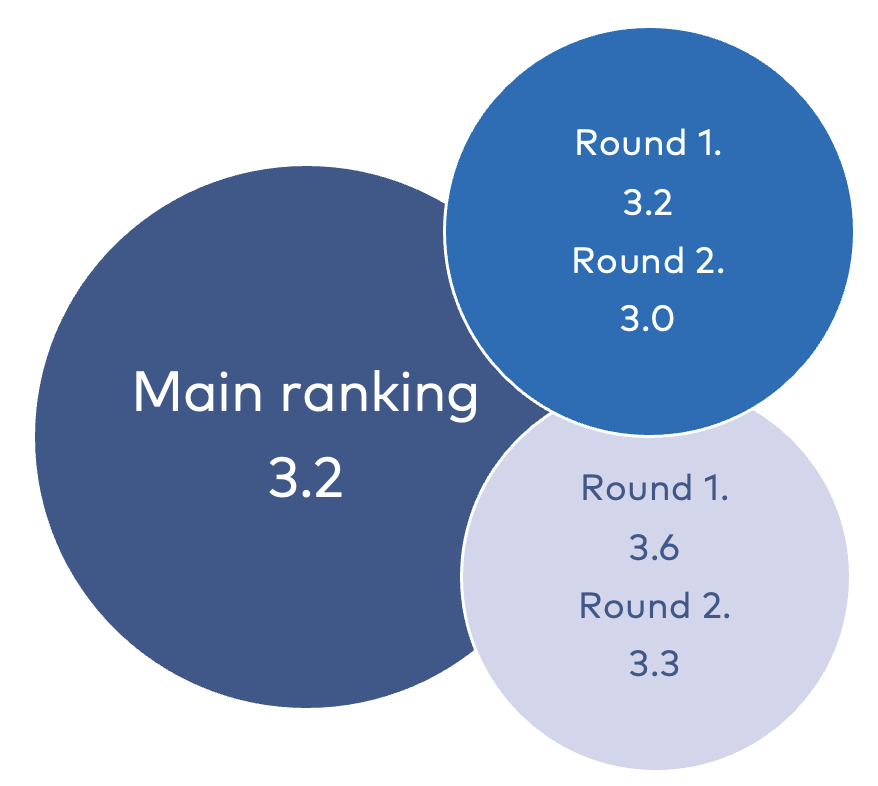

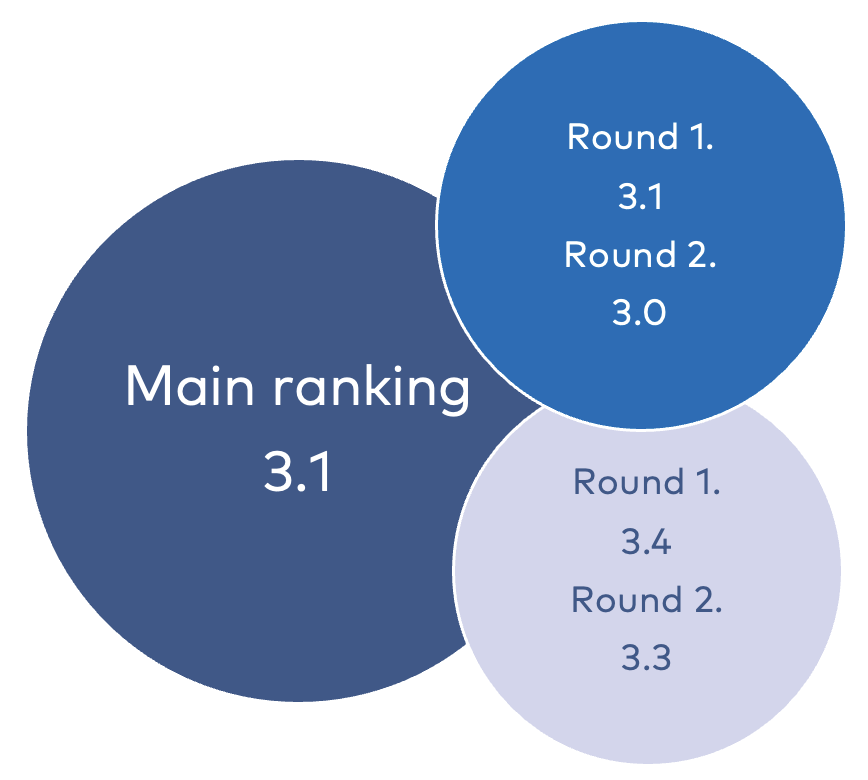

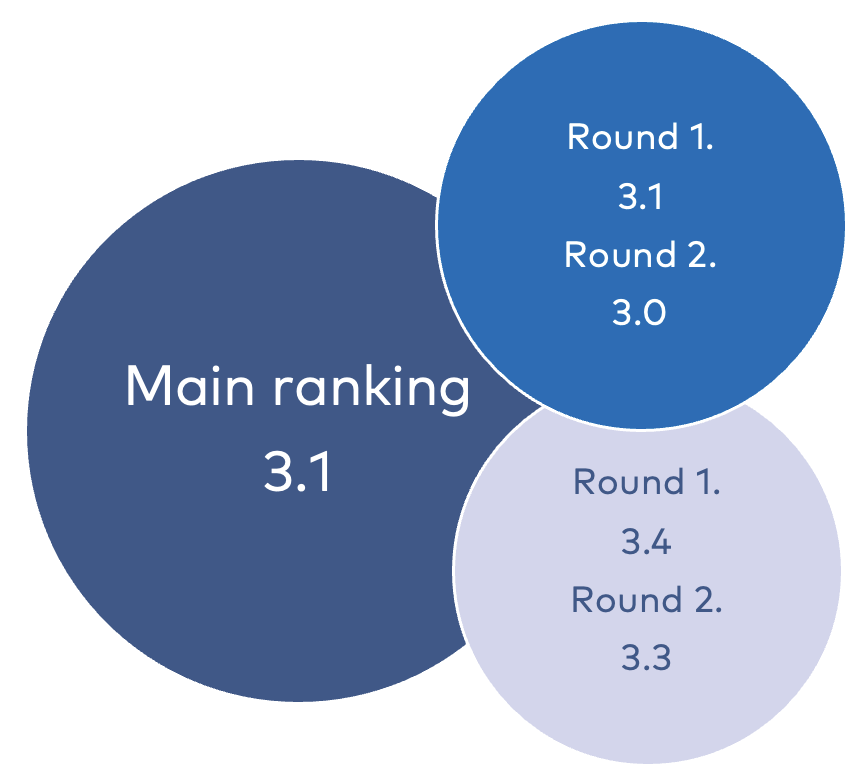

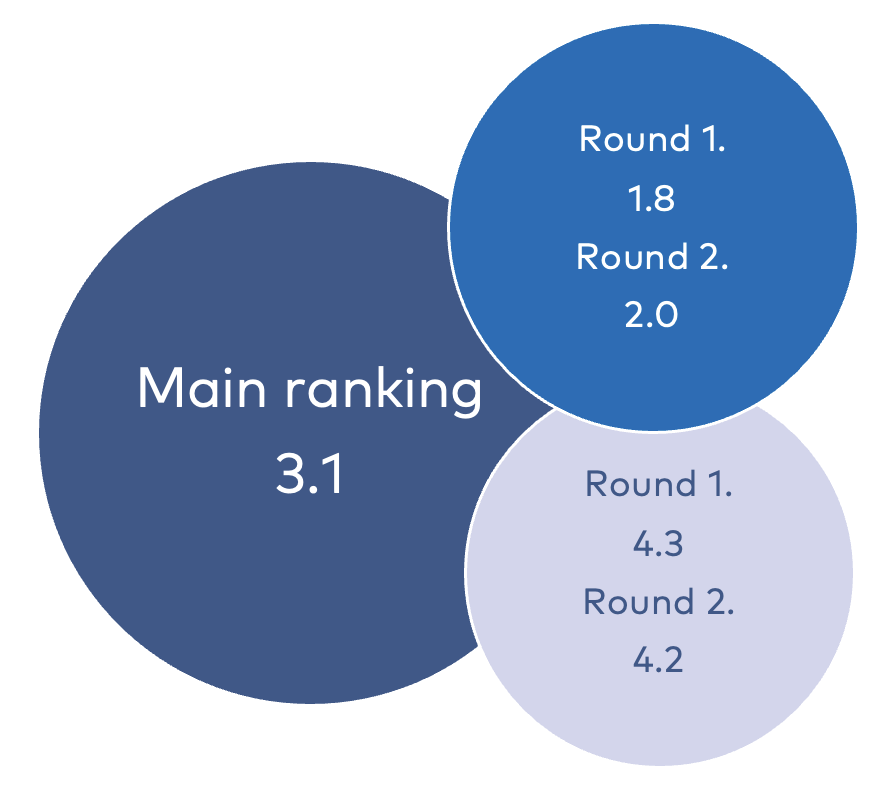

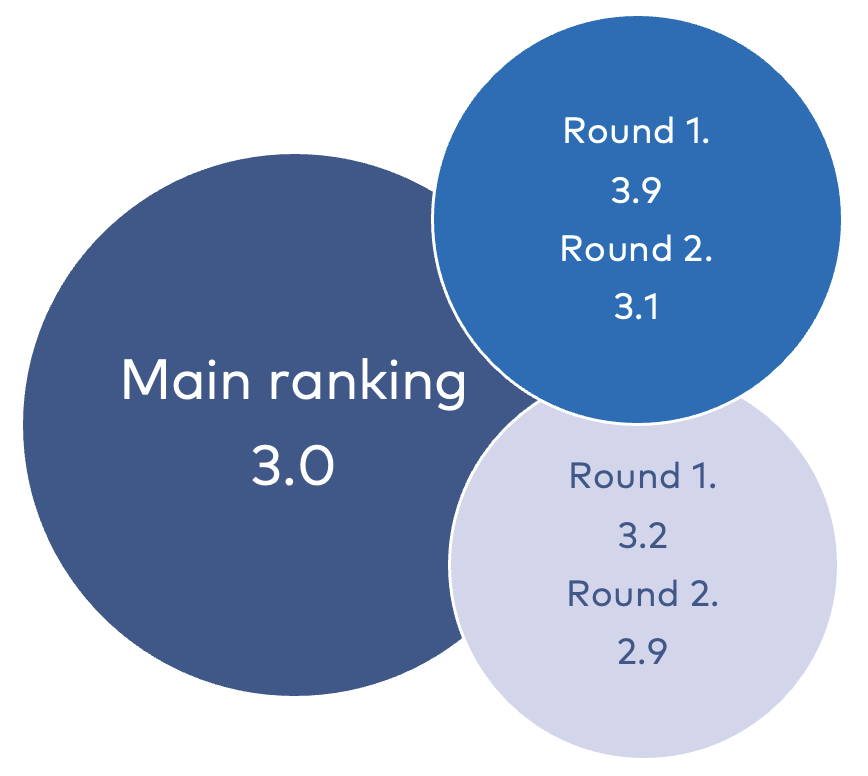

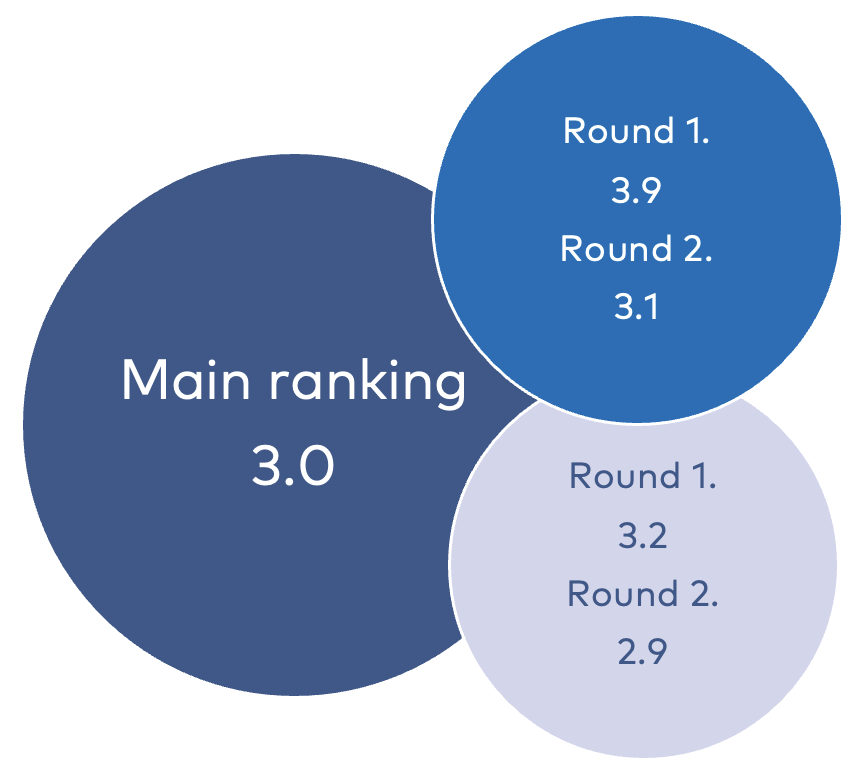

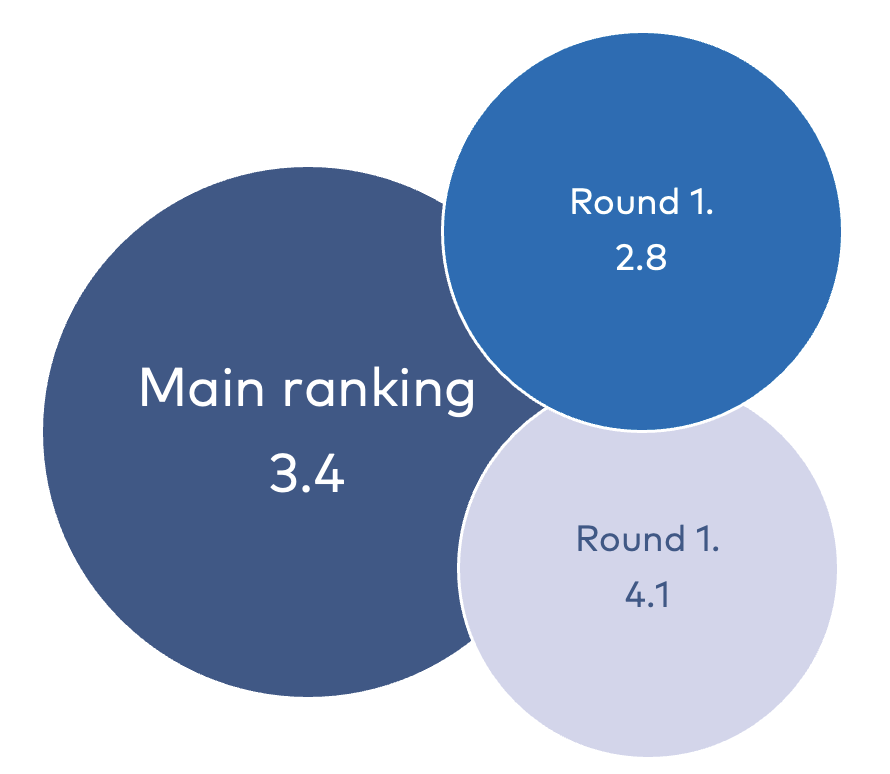

We selected twenty-one of the long listed consumption-based policies for the Policy Delphi (Table 6). Out of these twenty-one policies, twelve were ranked further in round 2. In Figure 13 the final twelve policies are listed alongside their respective mean ratings. We observe that experts take each other’s objections seriously and adjust their rankings downwards.

Figure 13. Highest to lowest overall ranking (round 2)

Figure 13. Highest to lowest overall ranking (round 2)

For each of the studied policies in round 2 we show the rankings assigned by the 23 participating experts, using bar diagrams (below). The diagrams highlight the relationship between potential to reduce emissions and feasibility rankings but they also show the spread of rankings assigned by the experts.

Regulatory Standards

Regulation of emissions, energy use, material use, etc, related to the production of products.

Regulation of emissions, energy use, material use, etc, related to the production of products.

The use of regulatory standards is ranked high among experts, especially in terms of potential to reduce emissions. As one expert puts it: “Feasible and effective since it puts demands on producers - same rules for all and long-term change, often acceptable for companies (as well as consumers).” In the words of another expert: “Strong instrument!”

Participating experts discussed examples, including EU’s requirements related to cars and the Ecodesign directive. They believe public acceptance would be high, e.g.: “It could be a way to mimic the effect of a much higher carbon price with potentially less public backlash.” However, even if the general population is in favour of legal standards, these could be “met by resistance from producers.” To prevent production from moving to countries with looser regulations, “regulations must also include imported goods, and produced goods from other countries.” Another objection is that there is a risk of rebound effects, i.e. that “the reduced emissions lead to an increase in the demand for the products.”

Others commented that monitoring would be a challenge and that the use of regulatory standards is “feasible with some products, not with many.” They observed that while regulatory standards work well for specific examples, such as cars and aluminium, the conditions of production for these goods may be difficult to replicate. They are often situated within the administrative boundaries of the regulatory body (e.g. EU) and dominated by a few producers. Thus, ”[i]mplementing and monitoring similar regulations in economy-wide scale for all product classes which are manufactured in a less geographically or producer condensed manner would be far more difficult and the related costs/uncertainties would be extremely high.”

+ same rules for all

+ generally high feasibility and potential to reduce emissions

- works better for few large producers than for many small

- risk for production moving to other countries

+ same rules for all

+ generally high feasibility and potential to reduce emissions

- works better for few large producers than for many small

- risk for production moving to other countries

Public Procurement

Requirements that public agencies must choose low or zero-emission products or services when available.

The mean ranking for public procurement is among the highest of all policies, especially concerning feasibility. Mean rankings did not change between the two rounds but remained high. The overall mean score of this policy measure is explained by an above-average ranking of potential to reduce emissions together with a high ranking of feasibility.

A new report from the Nordic Council of Ministers (2023c) suggests that public procurement policies related to food could benefit population health and the environment. Experts point at both direct and indirect effects of such policies. Some experts suggest that there may be limited direct effects but substantial indirect effects, e.g.: “Only 2–3% of food sales are to schools, hospitals, etc in Sweden, and the climate impact per meal in schools are already MUCH lower that private meals (…), however the indirect effect could be substantial. If kids were served only vegan food in 12 years it would make them used to it.”

The general message is that public procurement is a “relatively feasible measure that is currently underused” and that is important to not only focus “on GHG emissions (and other air pollutants) but also the impact of other harmful substances (e.g. pesticide use) and loss of biodiversity.” Experts mentioned that sectors other than those studied in this report might be more important in terms of reducing emissions: “Most important sector in terms of CO 2 from public consumption is likely the use of cement in infrastructure” , a sector with large emissions and with already existing low emission alternatives.

However, some concerns were raised. One expert observed that existing regulations could limit green public procurement: “Our experience is that sometimes the laws need to be revised to allow the procurement.” Another raised concerns about the importance of price in procurement: “ it also tends to be that price dominates no matter what other criteria exist.”

+ generally high feasibility and potential

+ substantial indirect effects

- “Feasibility depends on the political parties in office”

+ generally high feasibility and potential

+ substantial indirect effects

- “Feasibility depends on the political parties in office”

Reduce Incentives that Promote Commuting to Work by Car

Tax deductions for expenses related to workers’ commutes should be neutral in relation to transportation type.

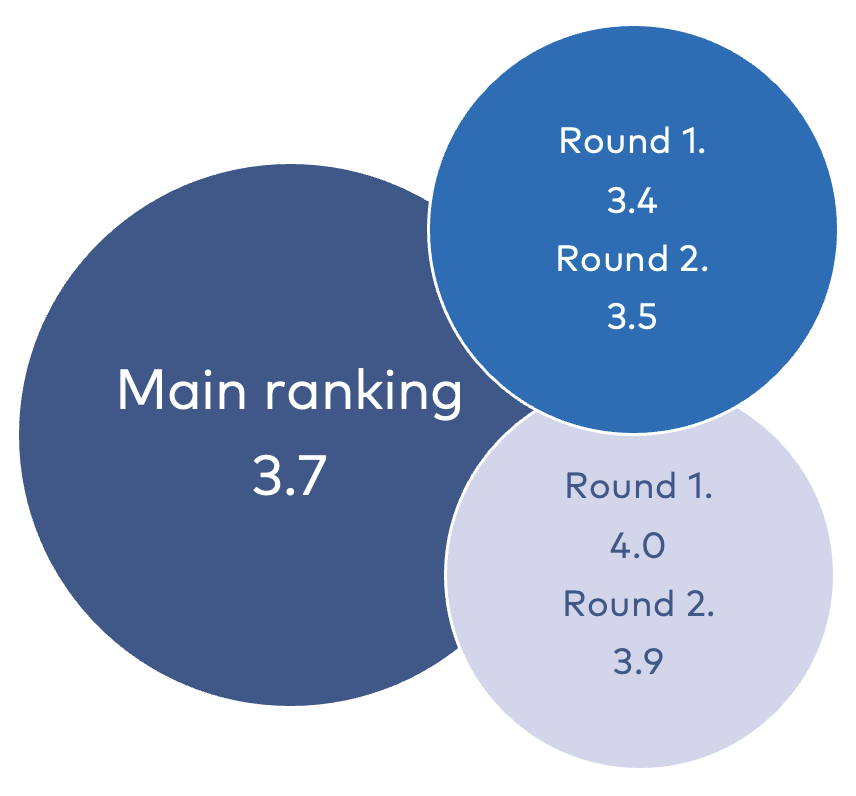

The ranking for potential to reduce emissions marginally increased between round 1 and round 2. However, the ranking for feasibility marginally decreased. Mean ranking remained high, at 3.7, in both rounds.

There is a general agreement that a system of subsidizing commuting by car, especially subsidizing it more than commuting by public transport, is problematic. As one respondent expressed it: “ [i]t is somewhat crazy that car use is subsidized beyond public transport and active modes. ”

Others raised concerns that policy changes that reduce incentives to commute by car might have distributional effects. This concern was expressed by one expert as: “[t]his initiative is key but may have distributional effects in areas where public transport are weak” and by another as: “Needs to be considered how this will effect people in more sparsely populated areas.” Thus, offering alternatives to using your own car is crucial. “Making it easier, cheaper, and more favorable to travel by public transportation” has changed the way people travel in Norway. “Oslo has made large changes, with a huge effect the last decades to remove cars from the city with a combination of initiatives. Tax might be favorable, but not the most visible and effective one in changing travel behavior.”

It was noted that the distributional effect of this policy might be progressive, which might help with acceptance and perception of fairness. The current commuting policy design favours men, since men are overrepresented among those commuting by car. Thus, as one expert noted, changing the incentives for commuting is important for gender equality.

Although the potential to reduce emissions might not be huge, there is a general agreement that a changed policy is desirable: “Maybe it is not the biggest potential as it is debatable how much this motivates commuting by car, but the signal might matter and it should be feasible enough.” For example, in Denmark this is already in place: “In Denmark, the deduction is purely based on the distance to work and not related to the mode of transportation, which shows that it's feasible to do.” One objection against a purely distance-based policy is that low-emitting means of transport should be prioritized and subsidized higher, alternatively, high-emitting means of transport should be taxed higher. Following this, the deduction should not be neutral in relation to transportation type.

The general response is that the suggested policy is “feasible and should be undertaken to even out the playing field.” One respondent expressed doubts in that: “in the car-dominated world we live in, the reality would be that not many political parties would be willing to campaign for this.”

+ “it is a weird subsidy that should be removed”

- those affected are likely to oppose

- low political feasibility in Sweden

+ “it is a weird subsidy that should be removed”

- those affected are likely to oppose

- low political feasibility in Sweden

Subsidies to Increase Demand for Low-Emission Products

Subsidies designed to increase consumer demand for low-emission products have the potential to push out technologies or practices with higher emissions. Subsidies can be targeted towards novel technologies and products as well as established ones.

Subsidies rank among the highest in both rounds, with a somewhat lower mean ranking in the second round. However, expert comments suggest there are several potential challenges with subsidies (if not supported by other policy measures). One argument is that while subsidies might help introduce new low-emission products by compensating for initial competitive disadvantages, they are not as effective as consumption taxes on high-emission products. A combination of subsidies and taxes could be more effective. Here, the expert group is quite split on whether subsidies targeting electric vehicles (EVs) are successful or not. Some noted that EV subsidies largely have gone towards affluent consumers, and one expert suggested that EV subsidies should be restricted to supporting small and low-cost EVs. Another expert observed a high risk of lobbyism playing a role in defining most technologies as “low-emissions” to gain subsidies. In general, there are several comments suggesting that existing fossil subsidies should be removed. Several experts, influenced by comments in the first round, favour a bonus-malus construction, where high-emission products and activities are taxed, to finance subsidies for low-emission products and activities.

+ generally high feasibility and potential

+ removal of fossil subsidies a potentially effective measure

- risk of subsidies benefitting affluent consumers and marginally better technologies

+ generally high feasibility and potential

+ removal of fossil subsidies a potentially effective measure

- risk of subsidies benefitting affluent consumers and marginally better technologies

Consumption Taxes

Many countries have consumption taxes based on emissions of greenhouse gases on petrol and diesel. This could be expanded to other product categories.

The mean ranking of this policy measure decreases between rounds 1 and 2.

One expert argued that consumption taxes can shift consumer behaviour. This expert observed that consumption taxes can shift consumer behaviour without putting domestic producers at a disadvantage, since imported goods would have the same tax. However, in the case of the Danish agriculture sector, which has a large export of food, calculations indicate that such taxes are significantly less effective in reducing emissions than production taxes. Therefore, to achieve the same reduction in emissions, consumption taxes would need to be much higher, likely facing resistance from both the public and commercial sectors. Others point to the possibility of compensating affected companies or people (in the case of regressive distributional effects), either by direct paybacks (see fee-and-dividend) or by making sustainable options more affordable. One expert stresses that consumption taxes should be implemented across all Nordic countries because of the significant cross-border shopping. There has been an interesting debate on an all Nordic taxation of meat and sugar which we will return to in Chapter 8: Discussion and Conclusion.

+ significant potential to reduce emissions

- possible unequal distributive effects

- low public acceptance (but possible to counteract)

- strong opposition from producers

+ significant potential to reduce emissions

- possible unequal distributive effects

- low public acceptance (but possible to counteract)

- strong opposition from producers

Consumer Guides and Dietary Advice

Mandatory information on the environmental and health effects of food items and diets directed at consumers.

The change between the two rounds is marginal, with a slight decrease in the estimation of the potential to reduce emissions and a slight increase in the feasibility ranking. Overall, the potential to reduce emissions was judged to be low, while the feasibility was judged to be high. Several experts noted that this type of guide and advice is already common but has limited effects on consumer behaviour. One expert observed that while foods with lower environmental footprints are often healthier, health arguments often have a stronger impact on behaviour. Others add that this measure could affect public meals, such as school lunches. Some argued that producers can be influenced towards more environmentally friendly production methods. Another aspect raised by respondents is that including environmental aspects in dietary advice might be sensitive amongst agricultural interest organisations.

There has been a lively debate about the recently updated Nordic Nutrition Recommendations (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2023c; 2024). We return to this in the report’s Chapter 8: Discussion and Conclusion. See also Consumption taxes above.

+ judged as highly feasible and possible to build on existent policies

+ has the potential to influence public meal providers and producers

- low direct potential to change the behavior of consumers

- resistance from agricultural interest organisations

+ judged as highly feasible and possible to build on existent policies

+ has the potential to influence public meal providers and producers

- low direct potential to change the behavior of consumers

- resistance from agricultural interest organisations

Carbon Tax

A carbon tax is currently levied on most fossil fuels in proportion to their carbon content. The tax could be expanded to include CO2 from fuels used for fishing and agriculture.

In a review of the consumption-based emission footprint literature, Ottelin et al. (2019) found that carbon pricing is the most widely supported policy recommendation. However, there is an extensive discussion on the regressive effects of carbon pricing (Ottelin et al., 2019; Dawkins et.al, 2023).

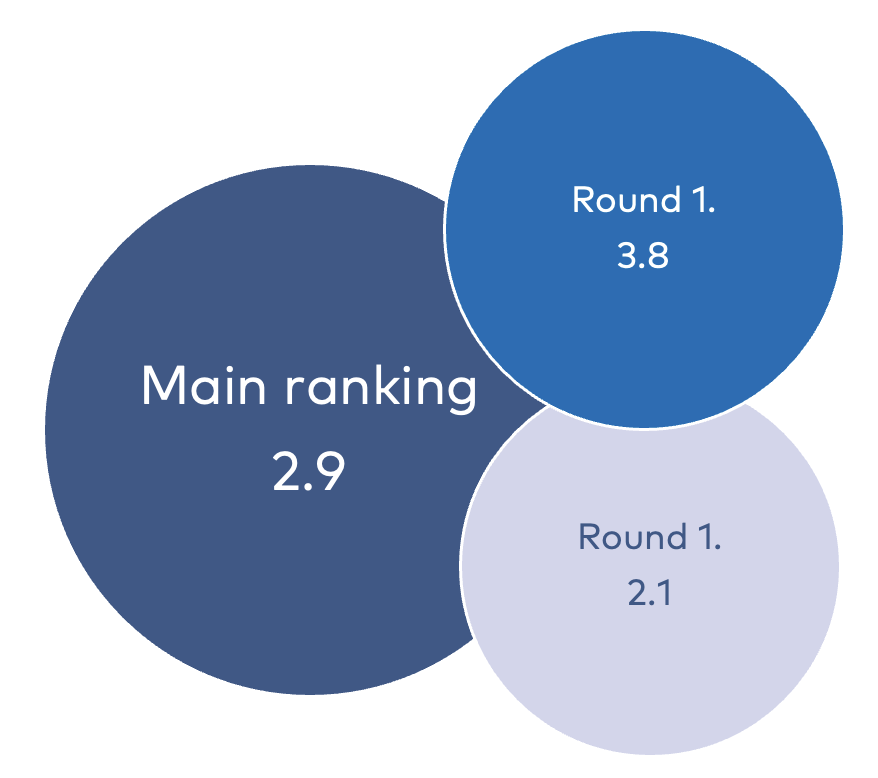

Next to a ban on short flights (see below) carbon taxation is the measure which falls most in the overall ranking between the first and second round (from 3.7 in round 1 to 3.3 in round 2). This ranking should be interpreted with caution because experts use competing definitions of carbon tax. Some experts interpreted the carbon tax as a proposed tax levied at agriculture, linked to current discussions about removing tax exemptions related to diesel used by farmers. Others interpreted the carbon tax as more extensive. With a focus on carbon taxation in the agricultural sector, several experts stress the importance of including taxes for other greenhouse gases (e.g., methane). Their concerns underscore the challenge of accurately measuring and monitoring other greenhouse gases in agriculture.

The comments indicate that most experts consider carbon taxes potentially effective in reducing emissions. The drawbacks include possible feasibility issues, resistance from affected sectors, and public acceptance. Some experts stressed these drawbacks more forcefully and argued that the levels needed for carbon taxation to be effective are rarely implemented and that the tax often has many exceptions.

One expert notes that a carbon tax is not aimed at consumers directly but, for instance, at fuels used in the agricultural or fishing industry. However, because of the common assumption that producers pass the costs of production on to consumers, carbon taxes are often included in classifications of demand-oriented policy measures. Some experts asserted that an EU-wide carbon tax would be preferable to prevent losses in competitiveness and carbon-leakage. Another expert argued that an EU wide tax very unlikely would pass the EU parliament since decisions regarding taxes need consensus.

+ high potential to reduce emissions (if applied to several sectors)

- risks strong resistance from affected sectors (and in the EU parliament)

- difficult to measure and monitor GHG emissions in agricultural production

+ high potential to reduce emissions (if applied to several sectors)

- risks strong resistance from affected sectors (and in the EU parliament)

- difficult to measure and monitor GHG emissions in agricultural production

Ban on Short Flights

A short-haul flight ban is a policy governments impose on airlines to eliminate flights over short distances.

A ban on short flights is, for instance, discussed by Dalhammar et al. (2022a) as a potentially strong policy measure to avoid consumption (as opposed to the dominant strategies of shifting and improving consumption).

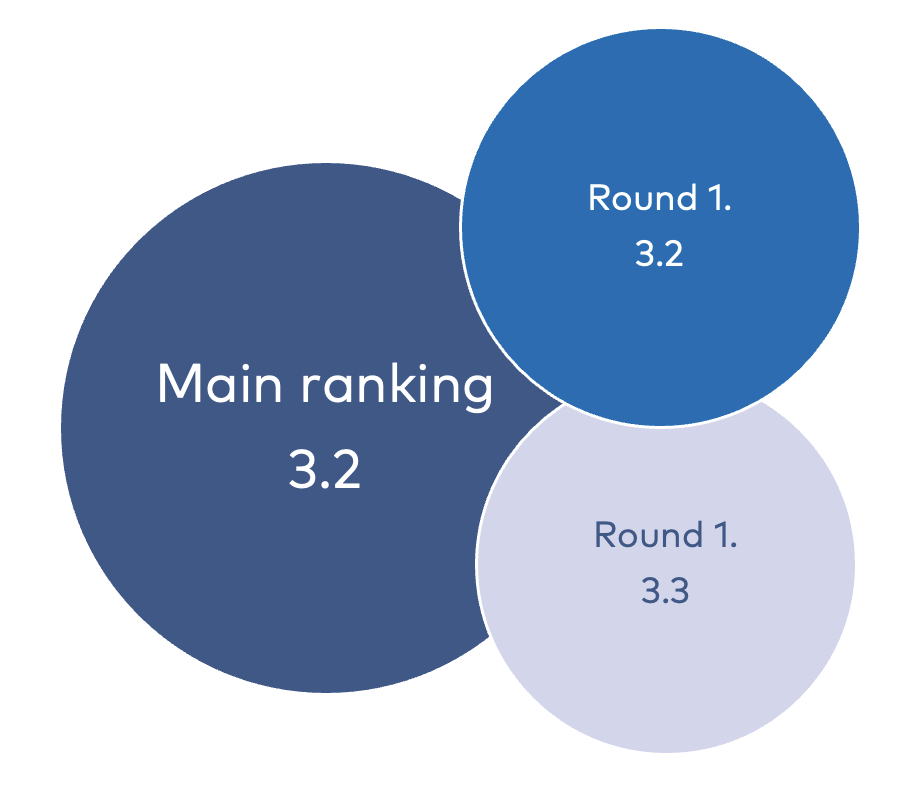

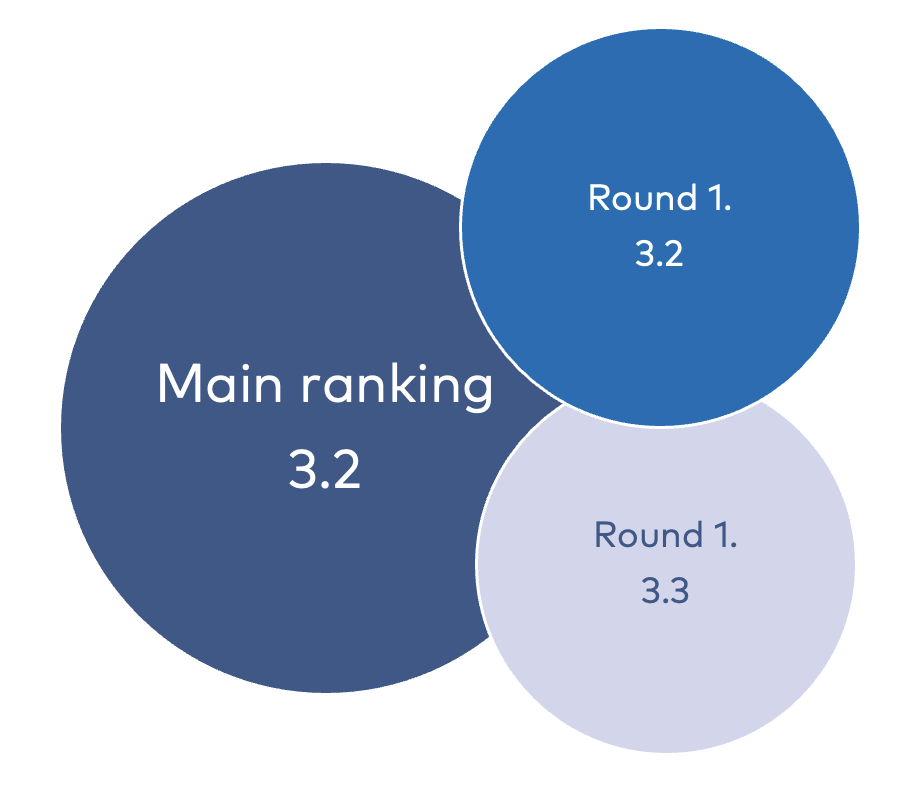

A ban on short flights is one of two policy measures which falls the most in the ranking between the first and second rounds (from 3.6 in round 1 to 3.2 in round 2). This decrease is largely explained by a drop in the ranked potential (note the missing values from respondents O and Q).

The prevailing argument against a high potential to reduce emissions is that short-haul flights represent a small part of aviation emissions. Some experts observed that the composition of aviation emissions differs between the Nordic countries, where short-haul flights are rare in Finland but more common in Norway. Some noted that effective short-haul flight bans would depend on the availability of transportation alternatives (e.g. train infrastructure). Referring to difficulties faced in France, a few experts saw major problems in monitoring and designing a ban on short flights. Most, however, judge this instrument as quite feasible with an important yet limited potential.

+ feasible on routes which are accessible by trains

- concerns a limited amount of air travel emissions

- difficulties in policy design and implementation

+ feasible on routes which are accessible by trains

- concerns a limited amount of air travel emissions

- difficulties in policy design and implementation

Fee and Dividend to Low-Income Households

Environmental taxes risk being regressive (i.e. disproportionately impacting people with low incomes). Targeted, compensatory measures have been proposed to mitigate this risk. Policy packages can combine e.g. consumption taxes with a tax refund for low-income households.

Increasingly, calls for compensation measures are raised in the context of fair transition discussions, and to create public acceptance of climate policies. Several studies indicate a high acceptance for fee and dividend policies (e.g. Ewald et al., 2022; Coleman et al., 2023). However, Matti et al. (2022), studying Swedish public opinions of fee-and-dividend in the context of air travel tax, found that this proposal was less favoured than redirecting revenues towards increased use of bio-fuels for aviation.

The expert group was split on this policy measure, although less so in the second round. The mean ranking was lowered from 3.4 in the first round to 3.2 in the second round. Those more positively inclined towards this measure underscored how it could create greater public acceptance of carbon pricing. Some argued, however, that general dividends to the whole population might create more public acceptance than focusing on low-income groups. Those more negatively inclined argued that refunds risk going towards increased consumption. Thus, rebound effects would reduce the potential to mitigate emissions slightly. One expert counter-argued that marginal spending generally has a substantially lower carbon intensity than the taxed consumption types. One category of objections to this policy measure related to administrative difficulties and national prohibitions that prevent ear-marking the use of taxes. One expert who was positively inclined about the measure argued that its feasibility is low because the Finish Ministry of Finance is very reluctant to earmark taxes.

+ increased public acceptance of carbon pricing

- risks of some rebound effects

- administrative difficulties

- political resistance against earmarking of taxes

+ increased public acceptance of carbon pricing

- risks of some rebound effects

- administrative difficulties

- political resistance against earmarking of taxes

Advertising Regulation

Advertisement restrictions place limits on the location, time, and methods by which products or services with high emission intensities can be marketed.

Advertisement regulations have for instance been analysed in relation to unhealthy and environmentally harmful food options (Statskontoret, 2019; Röös et al., 2021), and climate information on advertising for air travel (Larsson et al., 2019).

Disagreement among experts evaluating this policy measure was rather high and reflected in an extensive range of views in the comments. The disagreement did not diminish in the second round, instead, several experts noted counter arguments but decided to maintain a similar ranking. The distinguishing factor seems to be between those who see the potential of an advertisement ban as part of a bigger cultural shift and those who see a limited direct potential of regulating advertising. This dividing line also seems to pertain to banning specific forms of advertising or regulating advertising more broadly to limit its role in maintaining a consumerist culture. One expert stated that social media platforms are a context where citizens should have the option to opt out of advertising, similar to the right to deny paper junk mail in the mailbox. Another expert argued that a debate on advertising regulation could raise awareness and have an influence on its own.

+ signal value (affecting the societal debate)

- limited direct effects

- legal challenges for regulating advertisement on internet and TV

+ signal value (affecting the societal debate)

- limited direct effects

- legal challenges for regulating advertisement on internet and TV

Product Labels

Requirement to provide information on greenhouse gas emissions and other air pollutants on product labels.

Food is an area in which product labelling is common in relation to health effects. Many proposals for labelling to address environmental effects also exist (Röös et al., 2021).

Common discussions on product labelling consider whether the labelling should add positive markers to “good” products, negative markers to “bad” products or include neutral environmental declarations (Röös et al., 2021) or both of these (Thøgersen et al., 2024). A substantial scholarly debate exists on the effectiveness of product labelling in changing consumer behaviour (e.g., Majer et al., 2022; Potter et al., 2021).

The experts demonstrated broad consensus on the low potential to reduce emissions and the high feasibility of product labels in rounds 1 and 2. In round 2, the expectations for reduced emissions were slightly higher and expectations for feasibility slightly lower compared to round 1.

The expert comments did not include objections against product labelling in principal but raised several warnings about strategies that are over-reliant on changing consumer behaviour with informational approaches. One expert noted that recent research in Finland demonstrates that environmentally related information on food/lunch has less influence on consumer choices than the taste and appearance of the food. However, another expert, who ranked the policy higher than the mean value, argued that product labels can also influence producers to lower their emissions to improve the labelling. In general, the experts agreed that although product labels have little value on their own, they can be considered good additions to raise awareness and as parts of larger policy packages.

Product labels were included in the second round of the Policy Delphi, even though they received a low score in the first round, in order to analyse the expert discussion on informational policy instruments (which all received a low ranking in the first round).

+ has the potential to influence environmentally motivated consumers

+ could influence producers to lower their emissions

- has little influence on most consumer behaviour

- difficult (and possibly costly) to provide reliable emissions data on all products

- risks shifting the responsibility to the consumer and away from political action

+ has the potential to influence environmentally motivated consumers

+ could influence producers to lower their emissions

- has little influence on most consumer behaviour

- difficult (and possibly costly) to provide reliable emissions data on all products

- risks shifting the responsibility to the consumer and away from political action

Frequent Flyer Tax

A progressive tax on air travel, with an increasing tax, the more you fly.

The policy option of a frequent flyer tax was analysed by Larsson et al. (2020), which found that the Swedish public support was weak. However, this finding could be explained by the novelty of the tax, as survey answers tended to be more negative towards previously unknown proposals (Larsson et al., 2020). Matti et al. (2022) argued that a fee-and-dividend, which directs the revenues back to the public, is an alternative that could increase the support of a frequent flyer tax.

The experts raised questions about how a frequent flyer tax could be designed to increase its feasibility. Several experts commented on the possible integrity issues in registering all flights. A way to solve this problem, one expert suggested, would be to design a frequent flyer tax in such a way that the tax on one or two flights would be deductible in the yearly tax declaration. With this design, a state registry of flights would not be needed. If a person wanted to “hide“ having made a specific flight he or she could refrain from making the tax deduction. It was suggested that public acceptance of this tax could be increased if the frequent flyer tax was geared towards individuals with very large carbon footprints. Yet, it could also increase resistance from special interest groups (for instance, for business travel). Some experts discussed the challenge of establishing a tax that would be high enough to effectively reduce emissions, while being low enough to win public support (and not meet too much political resistance from special interest groups). If the tax level is too low, better-off frequent flyers could bear the cost and maintain their travel habits, while migrants flying frequently to visit family might be disproportionately affected.

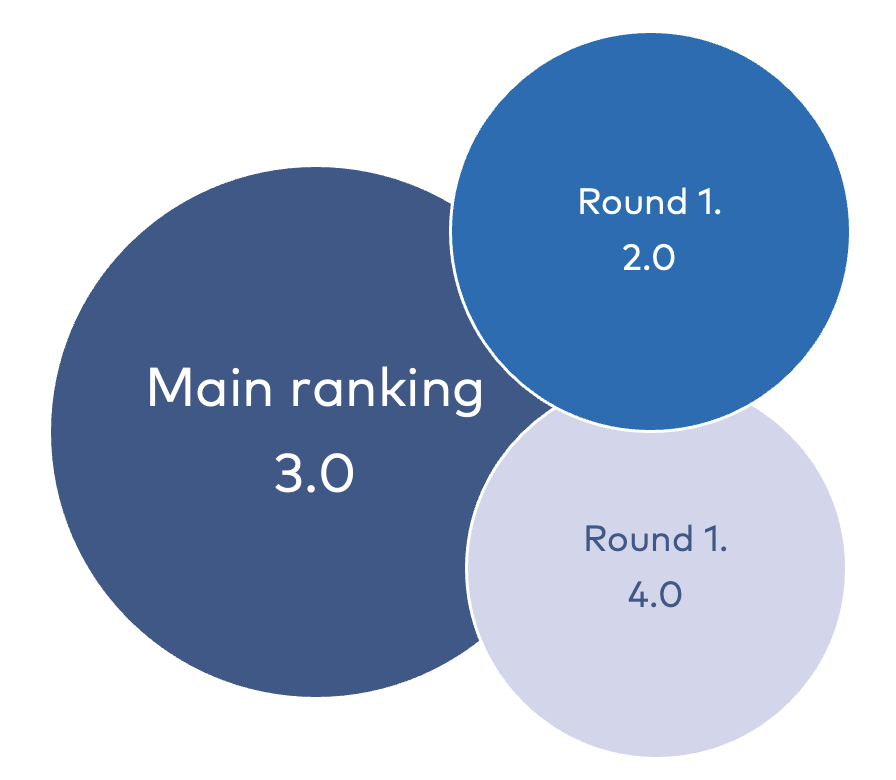

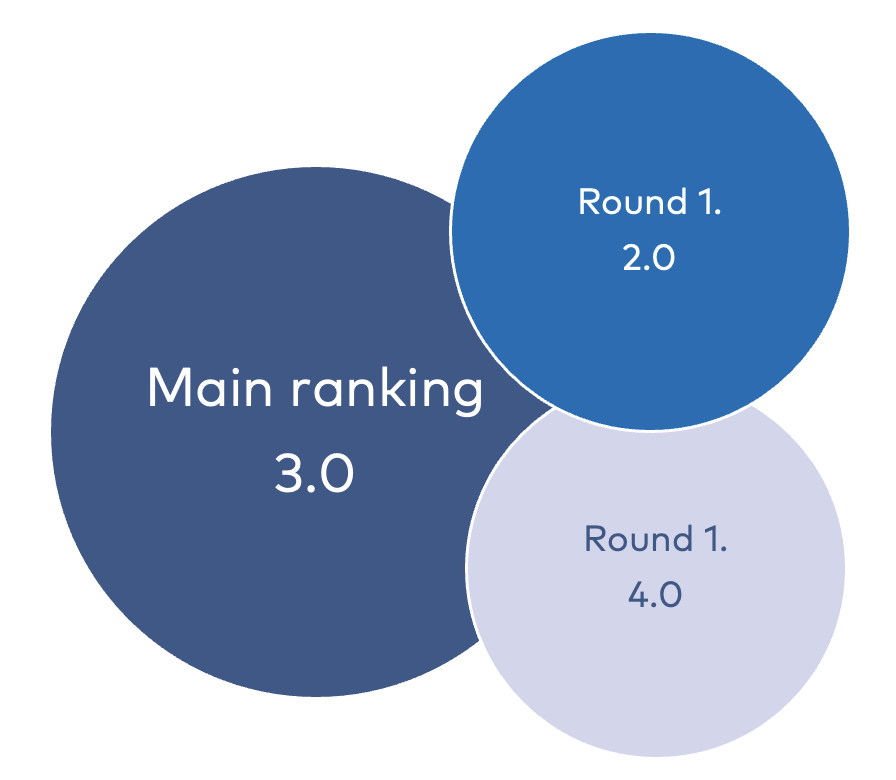

In the second round, more experts agreed that issues of monitoring the policy proposal constitute a considerable obstacle to its feasibility. Others agreed that less affluent groups would be disproportionately impacted by the tax. The mean ranking also fell from 3.5 points in round 1, to 3.0 points in round 2. Most, however, maintain that given the right design and information, a frequent flyer tax could become publicly supported because of its strong appeal to equity and fairness.

+ strong, fair transition appeal (frequent flyers can generate very large individual carbon footprint)

+ information about its content could raise the public acceptance

- integrity issues and administrative difficulties (can perhaps be solved by a tax deduction system)

- risks legitimising a one-flight-per-year norm

+ strong, fair transition appeal (frequent flyers can generate very large individual carbon footprint)

+ information about its content could raise the public acceptance

- integrity issues and administrative difficulties (can perhaps be solved by a tax deduction system)

- risks legitimising a one-flight-per-year norm

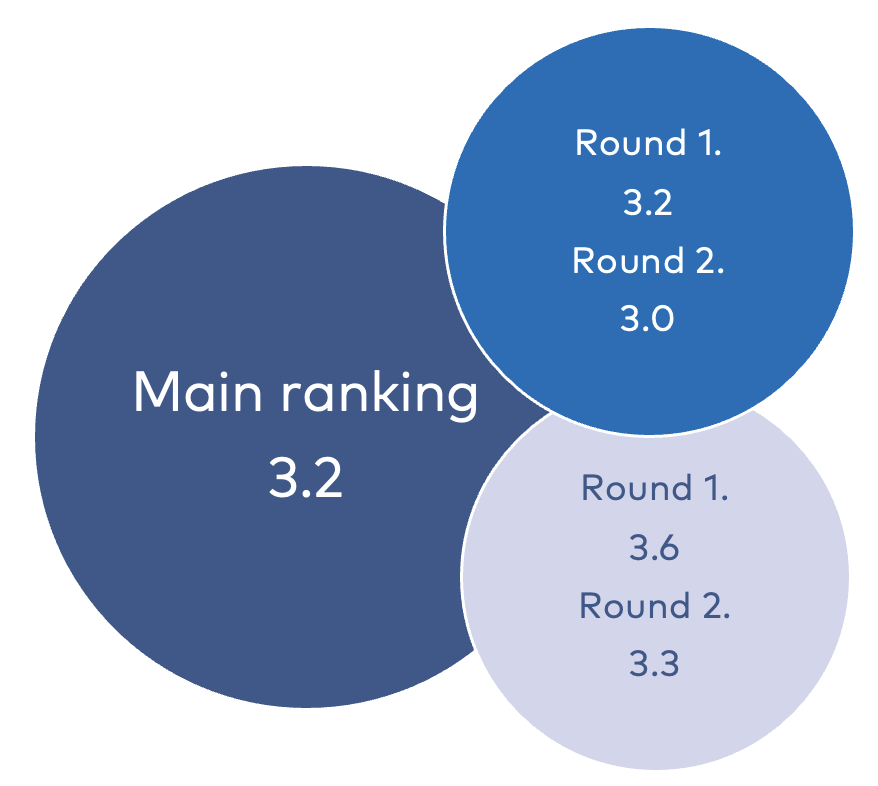

Round 1.

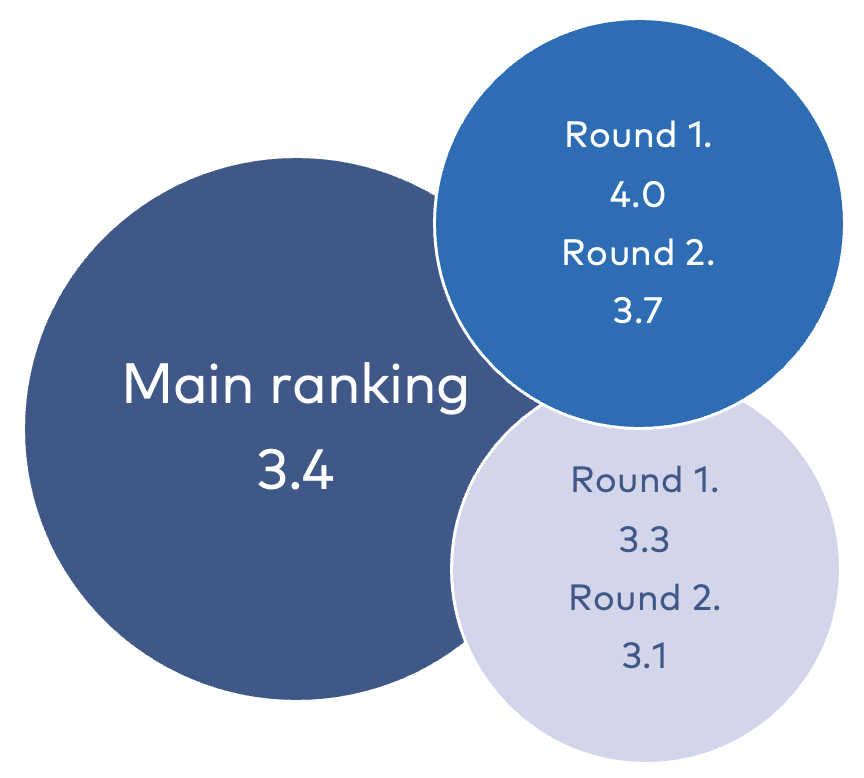

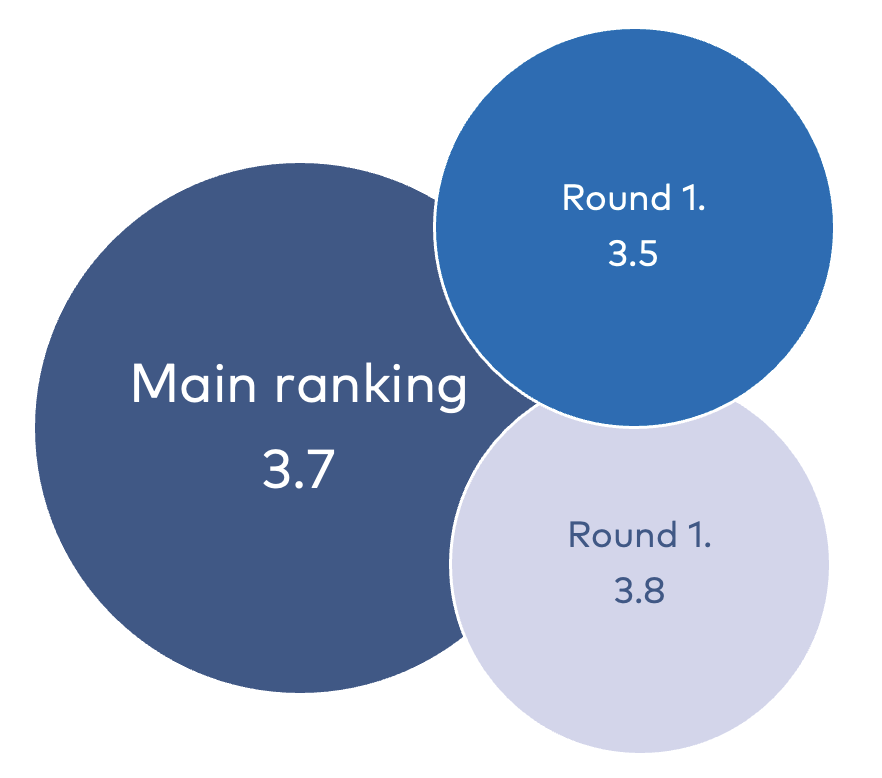

In Figure 14 and below, the results for the policy instruments that were only considered in Round 1 are presented. Comments from the Nordic expert group are summarised, including pros and cons with the respective policies. For each policy, the mean rankings of the potential to reduce emissions and feasibility estimated by the 23 experts are listed.

Figure 14. Selected policies for Policy Delphi round 1.

The policies are arranged from the lowest mean ranking (both “potential to reduce emissions” and “feasibility), “flight rights”, to the highest ranking, “extension of product lifetime”.

Extension of Product Lifetime

Enhancement of product lifetime, including bans on planned obsolescence, and on the disposal of unsold and functional products.

Ways to extend product lifetime for home furniture and textiles in Sweden are explored by Mont et al. (2021). Generally, the experts judged this policy measure as potentially effective, feasible, and necessary. This policy measure was not included in the second round of the Policy Delphi because it was judged to be best handled on the EU level (beyond the focus on national policy in this report).

+ has strong public support

+ possible co-benefits in reducing material use and creating new business opportunities

- hard to monitor and enforce bans on planned obsolescence

- trade-off with energy-efficiency gains of new products, such as new cars, fridges, etc.

+ has strong public support

+ possible co-benefits in reducing material use and creating new business opportunities

- hard to monitor and enforce bans on planned obsolescence

- trade-off with energy-efficiency gains of new products, such as new cars, fridges, etc.

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism

Importers who bring certain types of goods into the EU from third countries are obliged from 1 January 2026 to declare embedded emissions of greenhouse gases in the goods and to pay a fee corresponding to the costs for the European certificates for the embedded emissions unless they have already paid a corresponding tax or fee in the producing country. This policy measure could be used for different types of goods and for any air pollution or other environmental impact.

Climate tariffs on imported goods have been discussed for many years as a way to reduce embodied emissions and protect domestic industries from undue competition from regions with less stringent climate policy regulations (Persson et al., 2015). The joint foreign trade policy in the EU means that these discussions have led to an EU-level framework. One expert remarked that it is still uncertain if the non-EU member Norway will join the EU CBAM.

The experts’ comments underscored the expectation that CBAM regulation could protect European industries and jobs and facilitate more stringent climate policy, while pressuring countries outside the EU to price carbon. However, some experts were more cautious, warning that CBAM could cause trade conflicts and have negative economic impacts on exporting countries. One expert argued that more focus should be on collaborating with exporting countries to implement cleaner technologies (e.g., technology transfer and investments). The experts also noted difficulties in calculating embodied carbon emissions in imported goods, leading to overall issues of monitoring in any expanded CBAM regulation. Although the experts described CBAM as a key piece of legislation, it was not selected for the second Policy Delphi round based on the focus on national legislation for this report.

+ safeguards EU industries and jobs

+ incentivises exporting countries to price carbon

- potential trade conflicts and negative impacts on the economy of exporting countries

+ safeguards EU industries and jobs

+ incentivises exporting countries to price carbon

- potential trade conflicts and negative impacts on the economy of exporting countries

VAT Differentiation

Regulate the VAT so that it is lower on services and used goods, to promote repairs over new purchases.

Proposals for VAT differentiation are discussed in academic as well as non-academic publications. Examples include reduced VAT on services such as rental services, and hairdressing (Larsson and Nässén, 2019), differentiated VAT on food, based on health impact and environmental effects, including increased VAT on red meat and reduced VAT on fruit and vegetables (Röös et al., 2021).

The experts’ evaluation of VAT differentiation was generally positive. However, most experts deemed the overall potential as moderate. One expert noted that since most consumption causes emissions, a general raise of consumption taxes could be called for. Experts who have ranked the highest potential to reduce emissions (5), seemingly see a VAT differentiation as part of a larger VAT reform. Such reforms could substantially shift the cost between consumption categories towards categories with higher impacts and reduced costs on consumption categories with lower impacts. For the second round of the Policy Delphi, we have considered such proposals under the broader “consumption taxes” section. VAT differentiation was therefore not included in round 2, even though it scored fairly high.

+ already tested system (proposed in Norway and introduced and later removed in Sweden)

+ high public acceptance

- administrative difficulties and costs (making the VAT system more complicated and thus a less popular reform among tax authorities)

+ already tested system (proposed in Norway and introduced and later removed in Sweden)

+ high public acceptance

- administrative difficulties and costs (making the VAT system more complicated and thus a less popular reform among tax authorities)

Required Recycling

A ban on disposing products and materials that can be reused or recycled is introduced. The ban includes landfilling and incineration strategies of disposal.

Proposals for required recycling include requirements for the sale of leftover food (Parekh & Svenfelt, 2022). Such legislation has, for instance, been implemented in France and proposed in Norway. Experts note that regulation for waste prevention and management is favourable to implement across the EU.

Required recycling can be compared to enabling recycling, where the former has a higher potential to reduce emissions while the latter is deemed more feasible.

+ could facilitate a circular economy of recycled materials

+ should be combined with standards to increase recyclability

- landfilling of plastics could be favourable over incineration (which emits GHG, at least until Carbon Capture and Storage is in place)

- efforts to avoid waste should take precedence. This follows from the EU waste hierarchy (EU waste framework directive (Directive 2008/98/EC)

+ could facilitate a circular economy of recycled materials

+ should be combined with standards to increase recyclability

- landfilling of plastics could be favourable over incineration (which emits GHG, at least until Carbon Capture and Storage is in place)

- efforts to avoid waste should take precedence. This follows from the EU waste hierarchy (EU waste framework directive (Directive 2008/98/EC)

Enabling Recycling

Provide facilities for consumers to recycle products and materials at the end of use.

Enabling increased recycling is a commonplace proposal for sustainable consumption (Dalhammar et al., 2022b). Systems for recycling are common across the Nordic countries. The experts judge this policy measure as highly feasible, but it needs to be expanded to have a greater potential to reduce emissions. Expectations regarding the degree to which enabled recycling could reduce emissions are moderate. Several experts note that reductions in overall consumption that produce waste are more important. Moreover, longer lifespans of products, before they become waste, are also preferable.

+ an already existent and popular system which could be expanded

- moderate expectations of potential to reduce emissions

- efforts to avoid waste should take precedence

+ an already existent and popular system which could be expanded

- moderate expectations of potential to reduce emissions

- efforts to avoid waste should take precedence

Extended Producer Responsibility

Producers are responsible for collecting and recycling products at the end of use.

Proposals for extended producer responsibility (EPR) are, for instance, discussed by Schoonover et al. (2021) and Dalhammar et al. (2022b). New areas for EPR include consumer durables, such as furniture, which are not consumed often but have substantial environmental footprints. Several experts comment that the EPR is vital to promoting a circular economy. However, the policy design must facilitate production changes and not only confer extra costs to the customer. Moreover, EPR is insufficient and must be complemented by overall demand-side reductions for several types of products.

+ changes in design could increase recyclability

- needs the “right” policy design to change production and be effective

- could meet resistance from commercial interests

+ changes in design could increase recyclability

- needs the “right” policy design to change production and be effective

- could meet resistance from commercial interests

Conditioning Tax Deductions for Home Repairs

Tax deductions can be made for home repair costs if the repair increases energy efficiency or reduces the use of resources and materials.

In 2022, the cost for the ROT deduction for the Swedish government was 12 billion SEK, which is substantial. “The Swedish National Audit Office recommends that the government reduce the ROT deduction by designing it in a way that increases its cost-effectiveness in relation to the goal of combating undeclared work” (Riksrevisionen, 2023, p. 6, our translation). There is also a gendered bias to this policy. Following the Swedish National Audit Office, 60% of the tax deductions from ROT are given to men and 40% to women. Thus, our proposal is a green design of an existing policy.

One expert comments that Denmark has had a system for tax deductions in place, but it was removed in 2021. A similar system has also been discussed in Finland for many years but has not been implemented. An administrative issue that is brought up is that energy-saving renovations are often performed in combination with another refurbishment. Distinguishing renovations that conserve from those that increase energy and resources use could thus be difficult.

+ large potential in reduced carbon footprints for older buildings (in energy systems relaying on fossil energy)

- difficulties in administering deductions

- possibly unfair as it benefits homeowners, i.e. it is regressive (a critique valid also for the present ROT deduction in Sweden)

+ large potential in reduced carbon footprints for older buildings (in energy systems relaying on fossil energy)

- difficulties in administering deductions

- possibly unfair as it benefits homeowners, i.e. it is regressive (a critique valid also for the present ROT deduction in Sweden)

Information Campaigns

Information campaigns that inform consumers on products and behaviour that cause high emissions of greenhouse gases and other air pollutants.

An extensive body of research explores (and critiques) information campaigns aimed at promoting sustainable consumption (for instance, see Shove, 2010; Fischer et al., 2021). The expert judgments point at high feasibility and low potential to reduce emissions (the direct opposite of flight rights discussed below). The comments underline that information campaigns alone cannot change behaviour but may complement broader policy packages.

+ can increase the effectiveness and acceptance of other policy measures

+ high feasibility

- low potential to reduce emissions/little impact on behaviour

+ can increase the effectiveness and acceptance of other policy measures

+ high feasibility

- low potential to reduce emissions/little impact on behaviour

Flight Rights

Consumption can be regulated by allocating emissions rights to consumers. Flights rights can be used a proxy for emissions.

Flight rights, in terms of personal carbon allowances, have, for instance, been studied by Larsson et al. (2020). Their findings indicate that, at present, the Swedish public support for such a measure is low. Also, in the Policy Delphi, the experts express that the overall feasibility of flight rights is low while the potential to reduce emissions is high. This makes flight rights stand out, with the greatest discrepancy in ranked feasibility and potential. The potential to reduce emissions also extends beyond GHG, as reduced air traffic with current combustion technologies would also reduce other local air pollutants (e.g. NOx) and noise (Riley et al., 2021). Several experts note the administrative difficulties in setting up a system of flight rights and that the public registry of who travels where could be problematic regarding private integrity.

+ high potential to reduce emissions

+(-) equal rights are fair, but affluent frequent flyers could buy up quotas

- integrity issues and administrative difficulties

- low public support

+ high potential to reduce emissions

+(-) equal rights are fair, but affluent frequent flyers could buy up quotas

- integrity issues and administrative difficulties

- low public support

Cross-Cutting themes in the Policy Delphi

The iterating process of the Policy Delphi-method can be seen as a filter. Only policies that the panel of experts considered promising enough in terms of potential to reduce emissions and feasibility pass through the filter. Following this process, all 21 policies discussed in round 1 of the Policy Delphi have passed the filter once. The twelve policies discussed in round 2 have passed the filter a second time. This does not mean that other policies from the longlist are not promising. Some of them could have qualities not considered here.

Here we summarise a few key lessons from the Policy Delphi process. Very few policies are judged to have no potential or be fully unfeasible. Instead, most policies are seen as important, but have little impact on their own. The comments also make clear that many types of the included policy measures are implemented somewhere in some form at present, but that more stringent policy design and enforcement is needed.

An important issue which recurred in the comments is that of resistance/acceptance towards policy measures. Such resistance is understood equally in terms of public resistance, as in political resistance and resistance from commercial interests. At present much focus has been put on public resistance to policies, but our expert comments underline that resistance from commercial and other interests are important factors.

The question of resistance/acceptance is occurring at the level of policy proposal and policy design, in terms of implementing strong versions of policy measures, and the risk of public or commercial interests’ resistance. A fruitful direction for further exploration would be to analyse stronger versions of policy design for already existent policies (e.g. how to move from a weak to strong version of a certain policy). Relatedly, further research is needed to determine whether combinations of policy measures could make them more acceptable. That is, if a policy package consists of ‘sticks’ as well as ‘carrots,’ it could increase the feasibility of one or several measures. This question is highly relevant but outside the scope of this report.

Generally, there are low expectations on informational policy measurements. However, the fact that they have limited effectiveness on their own does not mean that they are unnecessary. It is more accurate is to call information campaigns insufficient. They should be expected to have limited impact if they are not combined with other policy instruments. In some contexts, information campaigns can be a necessary part of a policy package and/or a sequence of policy measures (for example, to create legitimacy for an environmentally progressive policy) or to convey and teach practical skills (Klintman, 2024, personal communication; Klintman, 2017). Information is seen as important to raise the public acceptance for stronger policy option. Following analysis in chapter 5 Policy and Acceptability: “Informational policies like labelling are often the most preferred type of consumer policy” .

The mean ranking of policy measures decreased in many cases in round 2 as the experts took in objections raised by others. This decrease may be read as a sign that the participating experts took the exercise seriously and allowed other experts’ comments to influence their own rankings.

Several experts noted difficulties associated with implementing consumption or carbon taxes, where consumption or businesses might move across borders. Examples include, how a Swedish flight tax could move air travel to Kastrup in Copenhagen, or Norwegian food taxes increasing boarder shopping in Sweden. This suggests that there is a need to harmonize consumption and carbon taxes across the Nordic countries. Harmonized tax levels would disincentivize shifting consumption over boarders and create equal terms of competition between Nordic businesses.