1. Introduction and Background

The transformation of the Nordic countries' economies towards sustainability is gaining momentum on a broad front. In all Nordic countries, new cleantech companies are emerging, and established industries are transitioning their production to limit their impact on the surrounding environment. At the same time, a significant portion of the Nordic countries' environmental impact is caused by our consumption, both from domestic goods and services, and from imports, where production often takes place in countries with weak environmental regulations.

The Nordic Council of Ministers expresses this as follows: “Nordic consumption must change if SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals) are to be achieved.” They continue: “Nordic consumption has a huge environmental and climate footprint in other parts of the world. The Nordic Council of Ministers is working to turn this around and make the Nordic Region the most sustainable region in the world” (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2023a).

Climate targets are usually based on territorial emissions, i.e. emissions occurring within the country’s geographical borders. Territorial emissions are also reported to the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) and negotiated in international agreements. However, the consumption-based emissions of greenhouse gases

The most important greenhouse gases are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and F-gases (HFC, PFC, SF6 and NF3, which are used as e.g. refrigerants).

Politically, focus has lately been on climate change and emissions of GHGs. This is also mirrored in coverage in the media. However, much of what is said about climate and GHG emissions also holds true for other air pollutants like carbon monoxide (CO), ozone (O3), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2) and particulate matter (PM). Consequently, addressing one environmental problem could at the same time address other problems. Conversely, some climate mitigation strategies risk exacerbating other environmental issues, e.g., driving biodiversity loss. Reduced territorial emissions might in some cases also increase consumption-based emissions if dirty production is moved to countries with less environmental regulation. Nevertheless, addressing climate and other air pollutants could bring a range of non-environmental co-benefits to society. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2023, p. 31): “Many options are available for reducing emission-intensive consumption while improving societal wellbeing. Socio-cultural options, behaviour and lifestyle changes supported by policies, infrastructure, and technology can help end-users shift to low-emissions-intensive consumption, with multiple co-benefits.” Thus, the IPCC identifies challenges as well as expresses hope. This report delivers insights into how policies can support behaviour and lifestyle changes necessary to achieve a low-emission society.

Goals, main focus, delimitation and content of report

The overall goal of the project is to map out policy instruments to reduce consumption-based emissions (climate-impacting emissions and other air pollutants) on the national level in the Nordic countries. The project will also analyse policy instruments in terms of effectiveness, feasibility and distributional effects. Additionally, we will describe how consumption-based emissions have developed over time in the Nordic countries. The initial focus of the project, following the call from the Nordic Council of Ministers, was on policies targeting consumption of food, electronics, textiles and home furnishings. These consumption areas contribute significantly to emissions (both climate-related and other air pollutants) (Fauré et al., 2019). However, most policy instruments are not specific to particular product groups. The policies discussed here are therefore, in general, more broadly adaptable. Existing policies, as well as policies discussed but not implemented, or previously implemented but later phased out, are also studied.

Consumption–oriented policy options are here defined as actions by policymakers to change consumer behaviours. Note that such policy instruments may target individual behaviour, as well as the retail companies that market goods to consumers. Thus, the policy instruments may be directly consumer-based, or retailer-based, and may also influence consumption choices of industries in supply chains e.g. the choice of materials (Grubb et al., 2020). Policy instruments can also target public consumption. We have chosen consumption-oriented as a broad-scope term but recognize that this definition is similar to demand-oriented policy measures (which is a common term in some literature) (Grubb et al., 2020).

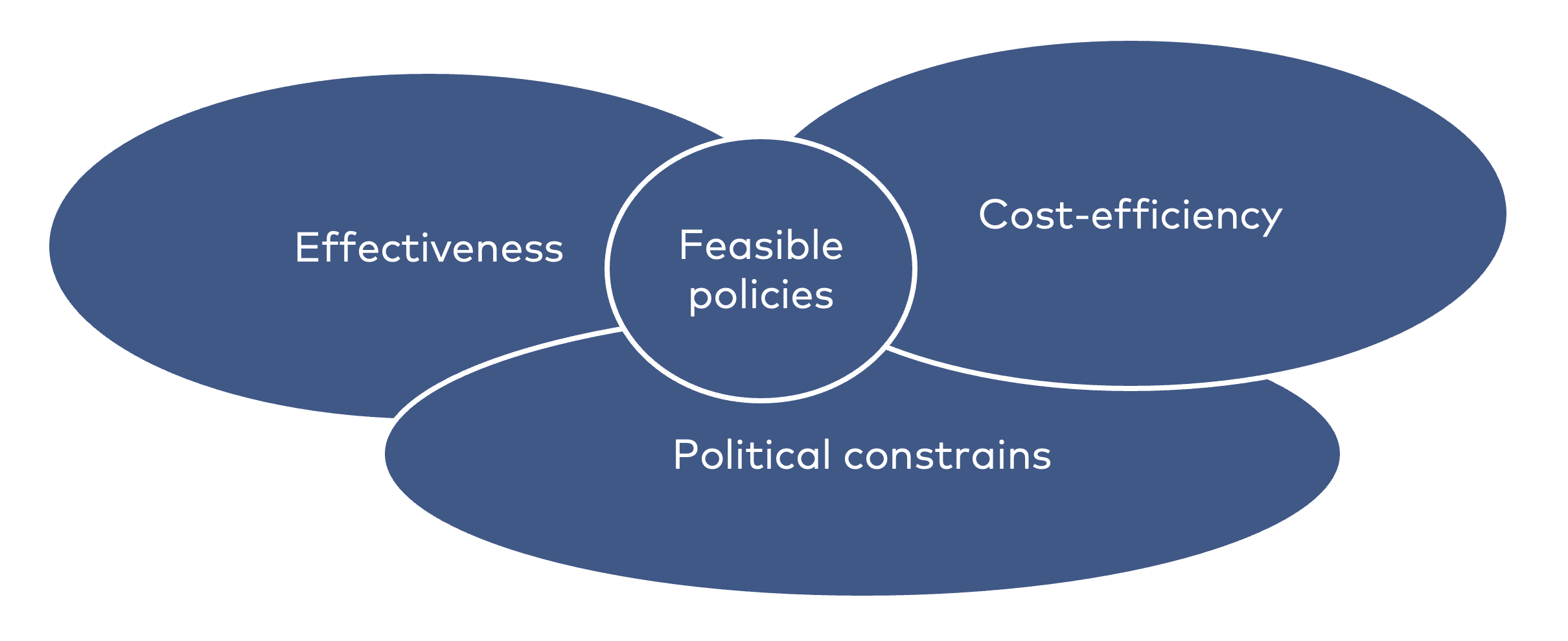

In addition to mapping policy instruments in each country, the Nordic Council of Ministers requested that "the distributional effects of the policy instruments be analysed, as well as aspects such as feasibility and [national or EU] competence". To this, we have added aspects such as effectiveness, i.e. goal fulfilment, and cost-effectiveness, as these aspects are also essential. These identified aspects together form the basis for a model, which can be found in similar combinations in models for policy analysis. For example, Figure 1 illustrates a model inspired by Jagers and Matti (2020), which places the "feasibility" of policy instruments at the intersection of effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and political constraints (or governance). Closely related to political constraints and feasibility is acceptability where low acceptability of a suggested policy could be a major constraint. We return to these issues in sections 5, Policy and Acceptability, and 8, Discussion and Conclusions, below.

Figure 1: Feasibility of Policy Instruments (based on United Nations, 2021; Jagers and Matti, 2020)

The Nordic Council of Ministers' compilations of environmental policy instruments (e.g. Nordic Council of Ministers, 2023b) provide a good starting point for this study. The recurring report "The Use of Economic Instruments in Nordic Environmental Policy" lists the majority of the Nordic countries' respective economic instruments aimed at climate-impacting emissions, other air pollutants, and various other environmental issues (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2023b). The most recent compilation covers the period 2018–2021. To avoid duplicating previous surveys, we have based our work on the Nordic Council of Ministers’ existing reports.

The present report focuses on consumption-based emissions of both GHGs and other air pollutants. As with emissions of GHGs, the majority of consumption-based emissions of nitrogen and sulfur oxides, as well as particulate matter, occur outside Sweden's borders (Palm et al., 2019). It is reasonable to assume that the situation is similar in other small, open economies, including neighbouring Nordic countries. Since a significant portion of these emissions are associated with the combustion of fossil fuels, the primary sources will largely be the same as for greenhouse gases. Consequently, policy instruments aimed at climate-impacting emissions often also affect other air pollutants, and vice versa.

As the Nordic Countries pursue a broad spectrum of climate mitigation measures, there is a need to take stock of those implemented and proposed policies which could enhance reduction of emissions of consumption-based greenhouse gas and other air pollutants. The present project aims to conduct such a broad mapping of implemented and proposed measures. This aim also corresponds to an increased emphasis on the need for policy mixes, or policy packages, in the sustainability transition literature (Salo et al., 2023; Lindberg et al., 2019). A mix of policies is viewed as instrumental in unlocking transitions, as there is no single ‘silver bullet’, neither in climate mitigation, nor in reducing emissions of other air pollutants. Here, it is suggested that policymakers need to pay attention to a broader set of mutually reinforcing policy mixes or packages. The mapping in this report, presented in Table 6, offers a broad set of instruments from which policymakers could draw inspiration.

Furthermore, the Policy Delphi method, described below, facilitates in gathering expert rankings and judgments of the potentials and drawbacks of a limited number of policies. This method allows us to identify “promising policies” that the participating experts deem to have a high potential to reduce emissions and be feasible to implement.

In section 2 of this report, calculation methods for consumption-based emissions are described. In section 3, focus is placed on the Nordic countries. Similarities and differences are discussed both in terms of calculation methods and actual consumption-based emissions in the Nordic countries. EU perspectives of consumption-based emissions and consumption-oriented policies are presented in section 4, followed by a discussion on policies and acceptability in section 5. In section 6 we present methods used, including the Policy Delphi, and material used in the report. Results are presented in section 7. The report ends with section 8, Discussion and Conclusions, which also includes policy recommendations.