4. Outlook

This chapter will sum up and address open questions to be answered in future projects. Some of these questions have not been looked at in depth in this report but are still added as a reminder.

A sector under uncertainty

From a current perspective, it is hard to imagine a world without waste incineration, even in the long run. Assuming landfill as primary handling of waste should stop on a global scale, and with material recycling rates at the desired level, waste incineration capacity still might be needed to take care of hazardous waste streams and/or mixed streams that are difficult to recycle.

The future scale of the sector, however, is unclear and highly dependent on political choices and incentives, which will ultimately have a high impact on the importance of chemical recycling, material recycling and CCS. Investments in these new or expanding technologies have to be made under uncertainty, which highlights the need for clear guidelines and long-term policies.

Cost-driven risk of illegal waste handling

High gate-fees (caused by high CO2 prices) may open up for less serious actors entering the market. This risk has been highlighted by waste management actors and a recent abuse scandal in Sweden

Potential impact of CCUS on total incineration capacity

Whether CCUS technologies are deployed on a large scale in waste incineration may be a decisive factor for the sector’s future: even if circularity goals are met, the chances for a completely carbon-neutral waste sector seem slim without CCUS, given the predicted hard competition for renewable feedstocks. Once a capture facility is installed and running in at a waste incineration plant, it is fair to assume that this plant has a higher chance of survival even if incineration capacity as a whole should decline, both due to the ability to operate carbon neutral (or, in fact, carbon-negative if biogenic CO2 is captured and stored permanently instead of reentering the value chain) and considerable capital lock-in effects.

Purity requirements in chemical or material recycling

Due to the potentially long lifetime of plastic materials produced in the past, hazardous impurities in recycling streams will present a problem even when their use should be discontinued in virgin materials. Setting a reasonable threshold to the effort of separating these materials from more benign and thus easily recyclable materials will be an own optimization task.

Human behavior

Ambitions on sorting of municipal household waste are high and reality is way below the set targets in most Nordic countries; progress is necessary to improve the sorting of household waste using a combination of behavioral change, policy measures and technical development. Common efforts in identifying successful measures implemented could be an effective way for the Nordic countries to collaborate. Research projects addressing these aspects include WECOS (Waste-to-Energy in Sweden’s circular economy – Collaborative system dynamics modelling), a project which “aims at improving strategic decision-making regarding the production, use, and re-use of household waste and energy infrastructure through a model platform integrated with quantified human behavior.

WECOS: Waste-to-Energy (WtE) in Sweden’s circular economy – Collaborative system dynamics modelling https://mesam.se/projekt/wecos-waste-to-energy-wte-in-swedens-circular-economy-collaborative-system-dynamics-modelling/

Plastics

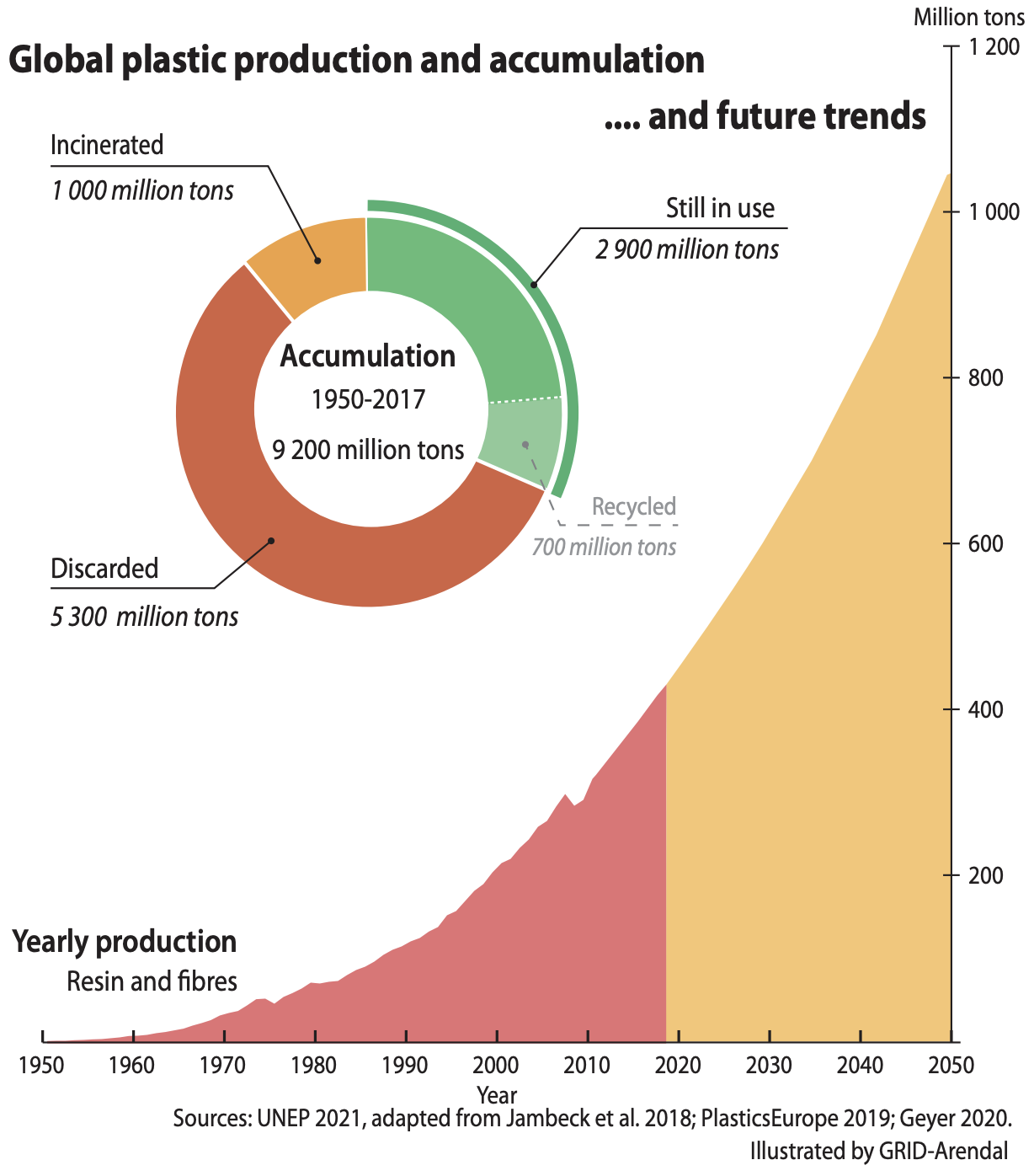

The global plastics market is expected to increase drastically in the coming decades, reaching a level of above 1 billion tons per year,

United Nations Environment Programme (2021). From Pollution to Solution: A global assessment of marine litter and plastic pollution. Nairobi.

Figure 25 Global plastic production and accumulation - historically and forecast

The cumulative global production of primary plastic between 1950 and 2017 is estimated to 9200 million tons (see Figure 25) and forecast to reach 34 billion tons by 2050.

Geyer, R. (2020). Production, use, and fate of synthetic polymers. In Plastic Waste and Recycling (pp. 13–32). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817880-5.00002-5

Plastics cause the highest share of fossil CO2 emissions from waste incineration – a fact that needs to be addressed if both national, Nordic and EU emission goals are to be reached. Higher recycling rates are the obvious answer to the question of how to reduce said emissions but are hard to achieve without substantial changes in the design, construction and production of new products containing plastics.

To achieve the necessary rates, a series of prerequisites need to be fulfilled:

- Recycling friendly product design.

- Increased (or, in fact, exclusive) use of recycled or biogenic plastics.

- A fair division of the cost incurred by these goals.

- Improved sorting technologies, leading to little or no reject to incineration facilities.

- A controlled way of handling hazardous materials in plastics, e.g., by forbidding these materials in new plastics and using waste incineration or chemical recycling to handle remaining hazardous materials from old plastics

In Denmark and Sweden – where the waste incineration sector is included in the EU ETS system – gate fees for waste management companies are rather high. There is a relatively high burden on materials being of service and use to society (in particular plastics) at the end of the value chain. Extracting fossil fuels for plastics and material production on the other hand is comparatively cheap. In case the cost for producing plastics do not incorporate the whole lifecycle cost in the near term, it can be expected that plastic volumes will increase heavily instead of decline.

Bauer, F., Tilsted, J. P., Deere Birkbeck, C., Skovgaard, J., Rootzén, J., Karltorp, K., Nyberg, T. (2023). Petrochemicals and Climate Change Governance: Powerful Fossil Fuel Lock-Ins and Policy Options for Transformative Change Work Plan. Retrieved from https://portal.research.lu.se/en/publications/petrochemicals-and-climate-change-powerful-fossil-fuel-lock-ins-a

To recycle or not to recycle

Current recycling goals are formulated under the assumption that once waste has been produced (i.e., the first steps of the waste pyramid are not applicable), material recycling is the best option from an environmental point of view. Future progress in e.g., chemical recycling technology might challenge that view.

District heating without combustion?

It is, in theory, possible to adapt district heating networks in a way that phases out combustion-based heat supply, e.g., by using heat pumps. In that case, the resulting additional electricity demand and the flow temperatures necessary in a district heating network (typically above 80 °C in existing networks) are challenges to be solved. Generally, the deployment of low-temperature district heating networks will probably be necessary to increase the use of non-combustion heat sources. In that context, the long-term effects of the updated Energy Efficiency Directive

The economic viability of such systems will have to be evaluated considering the continued delivery of electricity (and thus, availability of relatively high-grade heat) from CHP plants.

The Nordics providing waste services for Europe?

As was pointed out before, the Nordic countries are well-suited for specializing in waste incineration and thus potentially taking care of other countries’ waste. However, relying heavily on imports when planning national or Nordic capacity needs is a risk in itself as it is not sure that other European countries would want to rely on the Nordics to solve a strategic national problem. That being said, the current Nordic incineration capacity already exceeds the domestic waste production as mentioned earlier. A situation constituting a substantial amount of waste import would therefore in no way be an unusual one to handle for the Nordic waste incineration sector.