15. Agriculture, forestry and other land use

15.1 Introduction and summary

In 2021, the entire agriculture, forestry and other land use sector (AFOLU) absorbed 14.4 million tonnes of CO2e across the Nordic countries. The greenhouse gas inventory splits this sector into two different categories, the agricultural sector (as part of the effort sharing sector) and the land-use, land-use change and forests sector (LULUCF). Methane and nitrous oxide are calculated in the agricultural sector, and carbon dioxide in the land-use sector. In addition, agricultural energy use (fuels, electricity) is accounted for in the energy sector.

Net emissions from the Nordic agricultural sector were 30 million tonnes of CO2e in 2021, corresponding to 20% of the total Nordic emissions, including the LULUCF sector. Excluding the LULUCF sector, the agriculture sector is responsible for 16% of total emissions in the Nordic region. From 1990 to 2021, the GHG emissions from the Nordic agriculture sector have been reduced by 4 million tonnes of CO2e, corresponding to a 12% emissions reduction in the sector.

The Nordic countries have followed approximately the same reduction path in the agricultural sector from 1990 to 2021, with reductions of 13% in Denmark, Finland and Sweden, 11% in Iceland, and 5% in Norway. Denmark, however, has contributed almost half of the overall Nordic agricultural emission reductions in the period, because Denmark is the country that accounts for most of the total Nordic emissions from this sector.

Figure 20 provides an overview of the Nordic agricultural sector’s GHG emissions.

Figure 20: GHG emissions from agriculture across the Nordic countries 1990-2021

Source: UNFCCC. GHG data from UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/topics/mitigation/resources/registry-and-data/ghg-data-from-unfccc

The Nordic LULUCF sector absorbed 45 million tonnes of CO2e in 2021, reducing the total Nordic emissions by 23%. From 1990 to 2021, the GHG absorption from the Nordic LULUCF sector decreased by 21 million tonnes of CO2e, corresponding to a 31% reduction in the sector’s GHG absorption. This was mostly due to the reduction of the forestry sink in Finland from absorbing, on a net basis, almost 26 million tonnes of CO2e in 1990 to emitting around 0.5 million tonnes of CO2e in 2021. Sweden experienced a slight reduction of 10% in their forest sink in this period, while Norway increased their forest sink by 58%. Denmark and Iceland both have net emissions from their LULUCF sector but have reduced these emissions by 65% and 2%, respectively, from 1990 to 2021 (see Figure 21, below).

Figure 21: Net CO2 emissions from the LULUCF across the Nordic countries 1990-2021

Source: UNFCCC. GHG data from UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/topics/mitigation/resources/registry-and-data/ghg-data-from-unfccc

In Nordic Economic Policy Review 2023, the implications of targets outlined in the Fit for 55 is explored for Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. The review concludes that despite the Nordic countries having more ambitious abatement targets than the EU, EU requirements for increasing the removal of carbon in the LULUCF sector are not necessarily satisfied under current national targets

Flam, H. & Hassler, J. (2023). EU versus national climate policies in the Nordics. Nordic Council of Ministers. Retrieved from, https://pub.norden.org/nord2023-001/introduction-eu-climate-policy-and-fit-for-55.html

Across the Nordic countries, very little has been achieved with regards to reducing the emissions from agriculture, as evidenced in Figure 21, above. Most initiatives have focused on reducing emissions from agriculture by targeting the activities on the farm and, despite talk about more demand-side initiatives, these have still to be implemented. For the forestry and land-use part of this sector, initiatives have been targeted at the rewetting and/or afforestation of wetlands and peatlands, but progress is slow.

Emissions and main country challenges from the following sections are summarised in the table below.

Denmark | Finland | Iceland | Norway | Sweden | |

Emissions, 1990 Mt CO2e | 14.0 | 7.2 | 0.7 | 4.9 | 7.6 |

Emissions, 2010 Mt CO2e | 12.2 | 6.4 | 0.6 | 4.5 | 6.7 |

Emissions, 2021 Mt CO2e | 12.2 | 6.3 | 0.6 | 4.7 | 6.7 |

Development, 1990-2021 | -13% | -13% | -10.8% | -5% | -12.7% |

Development, 2010-2021 | -0.1% | -1.8% | -4.1% | +4.6% | 0.9% |

Table 11: Emissions from agriculture across the Nordic countries – a summary

Source: UNFCCC. GHG data from UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/topics/mitigation/resources/registry-and-data/ghg-data-from-unfccc

Denmark | Finland | Iceland | Norway | Sweden | |

Emissions, 1990 Mt CO2e | 6.9 | -25.8 | 9.6 | -9.8 | -46.3 |

Emissions, 2010 Mt CO2e | 2.6 | -26.0 | 9.6 | -23.8 | -50.3 |

Emissions, 2021 Mt CO2e | 2.5 | 0.5 | 9.4 | -15.5 | -41.7 |

Development, 1990-2021 | -64.6% | +101.9% | -2.2% | -57.7% | +10.0% |

Development, 2010-2021 | -3.8% | +101.9% | -2.1% | +35.0% | +17.1% |

Table 12: Net emissions from the LULUCF sector across the Nordic countries – a summary

Country | Summary of main challenge(s) |

Denmark |

|

Finland |

|

Iceland |

|

Norway |

|

Sweden |

|

Table 13: The agriculture, forestry and land-use sector across the Nordic countries – a summary of main challenges

Political concerns such as carbon leakage, regressive effects, food security and rural development have led to only small emission reductions in the agricultural sector across the Nordic countries. Furthermore, a combination of climate change, demand for land for growing farms, and an increased demand for biomass, is challenging the forest sinks in the Nordic countries.

Across the Nordic countries, the following two main challenges need to be addressed:

- emissions from organic soils and securing a future net removal in the LULUCF sector

- transforming the agricultural sector in the Nordic countries.

In the agriculture, forestry and land-use sector, we see the following opportunities for creating added Nordic value through collaboration:

- knowledge sharing on carbon pricing in agriculture – risks and incentive structures

- Nordic research on climate accounting on farms and improving knowledge on ways to reduce emissions on the farm from livestock, such as manure management – including biogas production, crop cultivation and fodder additives to reduce methane releases from ruminants

- studies on examples of how to improve the conditions for producers of plant-based proteins, both in terms of research, education and regulatory frameworks

- targetting Nordic research and innovation funds towards plant-based production.

Challenges and opportunities are described in further detail later in the chapter.

15.2. Status of the agriculture, forestry and other land use sector across the Nordic countries

In Denmark, and according to the DEA, the agriculture and forestry sector emitted a total of 15.9 million tonnes of CO2e in 2021, accounting for 34% of Denmark’s total CO2e emissions. Agricultural processes alone emitted 12.1 million tonnes of CO2e, while land use for forest resulted in a removal of -3 million tonnes of CO2e. In 1990 the sector emitted 23.2 million tonnes of CO2e, and thus from 1990 to 2021 the total CO2e emissions from the sector was reduced by 32%

Energistyrelsen (2023, April). Klimastatus og -fremskrivning, 2023. Retrieved from, https://ens.dk/sites/ens.dk/files/Basisfremskrivning/kf23_hovedrapport.pdf

The Danish parliament has set a political target for the agriculture and forest sector at a 55-65% reduction of GHG emissions in 2030 compared to 1990 levels, not including emissions related to the energy consumption in the sector

Regeringen (2021, October 4). Aftale om grøn omstilling af dansk landbrug. Retrieved from, https://fm.dk/media/25302/aftale-om-groen-omstilling-af-dansk-landbrug_a.pdf

Energistyrelsen (2023, April). Klimastatus og -fremskrivning, 2023. Retrieved from, https://ens.dk/sites/ens.dk/files/Basisfremskrivning/kf23_hovedrapport.pdf

Furthermore, EU targets require reductions in emissions from Denmark’s agriculture and forest sector. According to EU’s Effort Sharing Regulation, Denmark must reduce emissions by 50% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels. The DEA estimates that Denmark has an accumulated additional reduction demand of 16 million tonnes between 2021-2030. Additionally, the DEA expects Denmark’s obligation in the LULUFC sector to be 9 million tonnes short in the period 2026-2029 and 2 million tonnes short in 2030.

Energistyrelsen (2023, April). Klimastatus og -fremskrivning, 2023. Retrieved from, https://ens.dk/sites/ens.dk/files/Basisfremskrivning/kf23_hovedrapport.pdf#page=26

In the DEA’s scenarios for reaching climate neutrality by 2050, emissions from the agricultural and forest sector account for up to 80% of residual emissions. Depending on the scenario, agriculture and land-use emit 11.1-3.3 million tonnes of CO2e, while forests emit 0.5 to -3.4 million tonnes of CO2e

Energistyrelsen (2022, September 23). Resultater for KP22-scenarier. Retrieved from,https://ens.dk/sites/ens.dk/files/Basisfremskrivning/resultater_for_kp22-scenarier_23-09-2022.pdf

Statsministeriet (14. december 2022). Regeringsgrundlag 2022, Ansvar for Danmark. Statsministeriet. Retrieved from, https://www.stm.dk/statsministeriet/publikationer/regeringsgrundlag-2022/

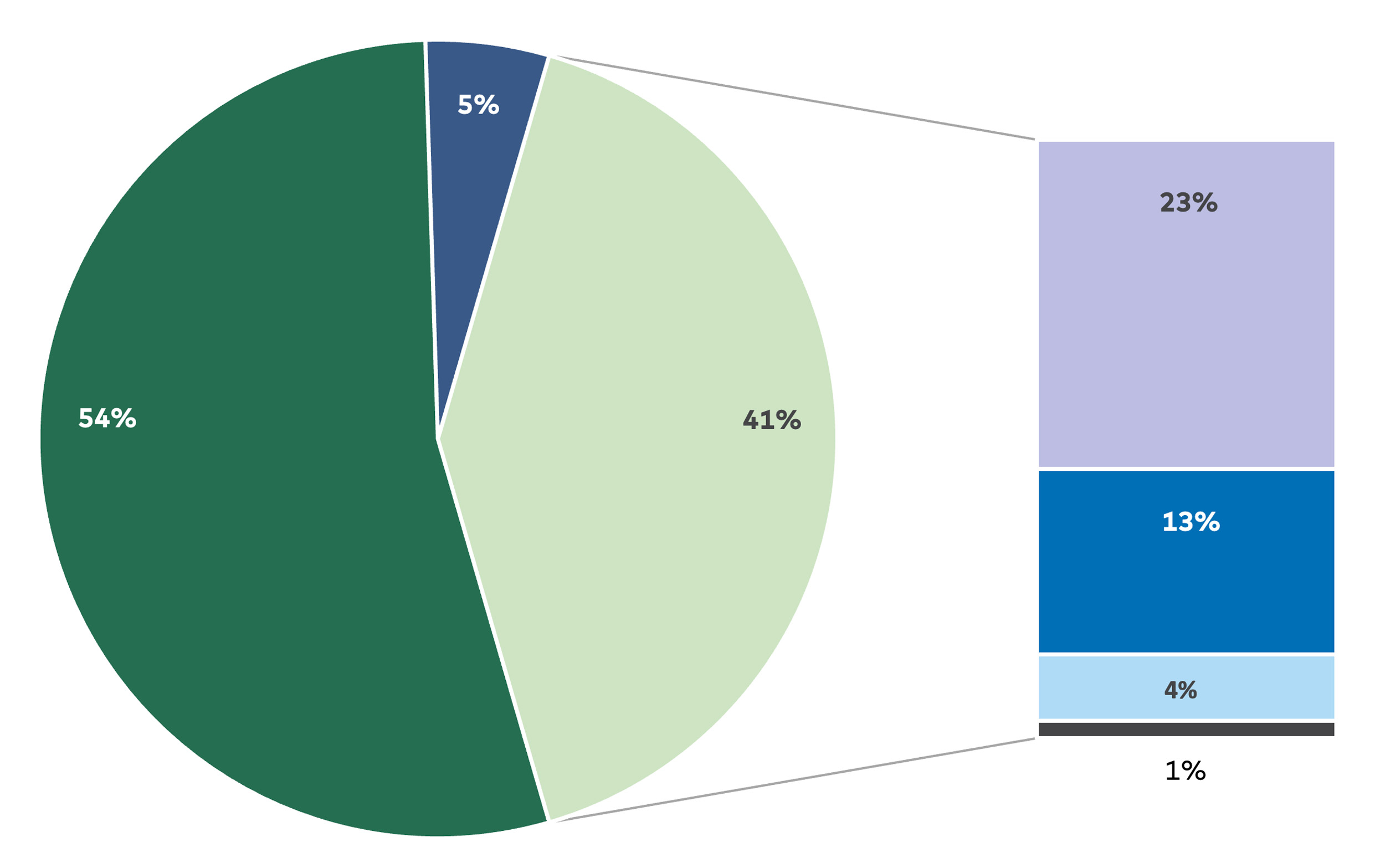

About a quarter of all emissions in Finland come from agriculture

Note that this includes all agricultural emissions - not only those under the Effort Sharing Regulation categorized as "Agriculture".

Lehtonen, H., Saarnio, S., Rantala, J., Luostarinen, S., Maanavilja, L., Heikkinen, J., Soini, K., Aakkula, J., Jallinoja, M., Rasi, S., Niemi, J. (2020). Maatalouden ilmastotiekartta – Tiekartta kasvihuonekaasupäästöjen vähentämiseen Suomen maataloudessa. Maa- ja metsätaloustuottajain Keskusliitto MTK ry. Helsinki. Retrieved from, https://www.mtk.fi/documents/20143/310288/MTK_Maatalouden_ilmastotiekartta_net.pdf/4c06a97a-c683-1280-65ba-f4666132621f?t=1597055521915

Figure 22: The distribution of agricultural emissions in LULUCF, effort sharing and energy sectors (2021)

Source: Ympäristöministeriö Helsinki (2022). Ilmastovuosikertomus 2022. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/164392/YM_2022_24.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

The Icelandic agricultural sector was responsible for 4% of total emissions in Iceland if including emissions from LULUCF, but 13% if excluding emissions from LULUCF. Total emissions from the sector have declined by 10.7% since 1990, trending slowly downwards largely due to a reduction in the number of livestock (sheep) in the country

Keller, N., Helgadóttir, Á.K., Einarsdóttir, S.R., Helgason, R., Ásgeirsson, B.U., Helgadóttir, D.,Helgadóttir, I.R., Barr, B. C., Thianthong C. J. Hilmarsson, K.M., Tinganelli, L., Snorrason, A., Brink, S.H. & Þórsson, J. (2023, April 14). National Inventory Report. Emissions of Greenhouse Gases in Iceland from 1990 to 2021. Environment Agency of Iceland. Retrieved from, https://ust.is/library/Skrar/loft/NIR/ISL_NIR%202023_15%20april_on_web.pdf

The LULUCF sector is instrumental in reaching climate neutrality but is also the culprit for significant GHG emissions, as the sector was responsible for 67% of net emissions in 2021. Forestry sequestered 509 thousand tonnes in 2021 with slowly increasing sequestration quantities since 1990 as more has been planted and older plantations mature to higher sequestration stages. Emissions have remained somewhat stable in other land-use categories since 2010

Keller, N., Helgadóttir, Á.K., Einarsdóttir, S.R., Helgason, R., Ásgeirsson, B.U., Helgadóttir, D.,Helgadóttir, I.R., Barr, B. C., Thianthong C. J. Hilmarsson, K.M., Tinganelli, L., Snorrason, A., Brink, S.H. & Þórsson, J. (2023, April 14). National Inventory Report. Emissions of Greenhouse Gases in Iceland from 1990 to 2021. Environment Agency of Iceland. Retrieved from, https://ust.is/library/Skrar/loft/NIR/ISL_NIR%202023_15%20april_on_web.pdf

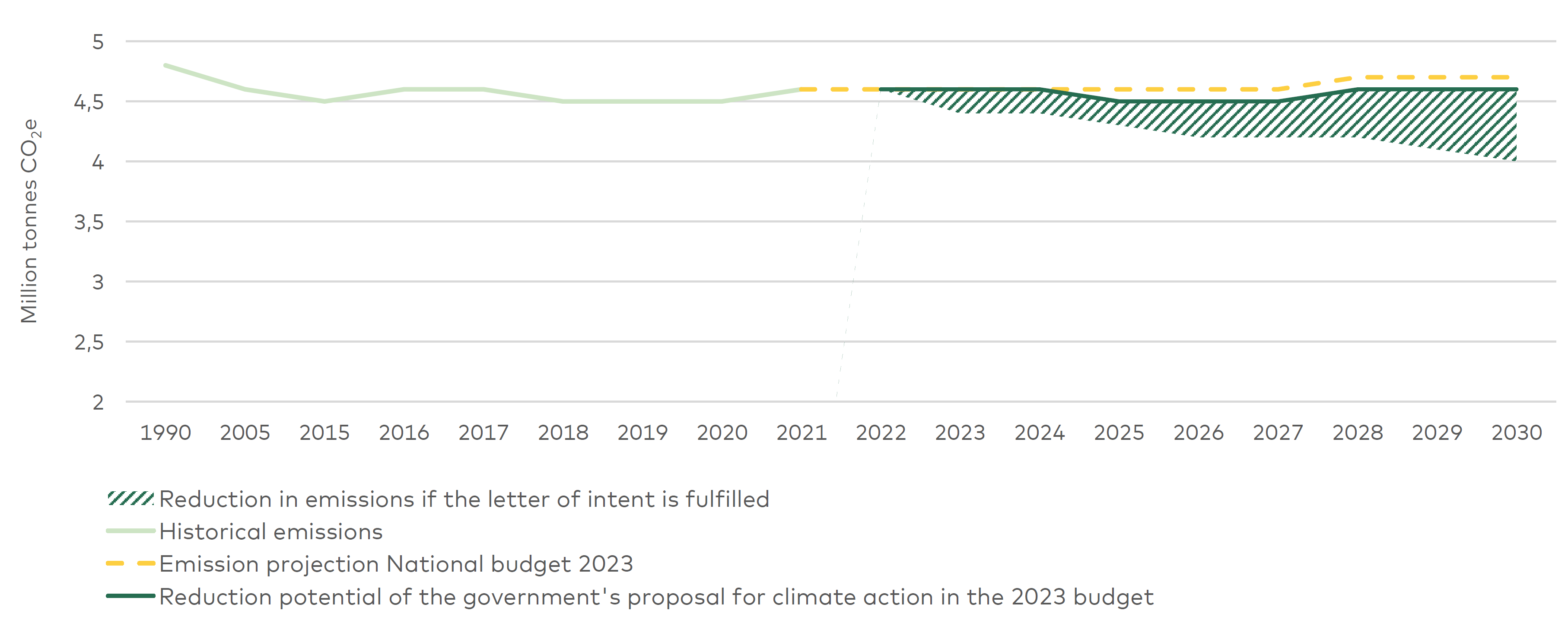

Agriculture was responsible for 9% of Norwegian GHG emissions in 2021, where the main sources are methane and nitrous oxide from ruminants and fertilizer use

Miljøstatus (2023). Norske utslipp og opptak av klimagasser. Norwegian Environment Agency. Retrieved from,

https://miljostatus.miljodirektoratet.no/tema/klima/norske-utslipp-av-klimagasser/ [Accessed 20.05.2023].

Figure 23: Historical GHG emissions from agriculture 1990-2021, with projections and mitigation effect of measures until 2030, million tonnes of CO2eq. (Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2022)

Source: Regeringen (2022). Regjeringens klimastatus- og plan. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/regjeringens-klimastatus-og-plan/id2931051/

Removal and release of GHG (mostly CO2) from land-use and land-use changes are included in Norway’s GHG accounting and reporting to the UNFCCC. Forest growth has generated a sizeable CO2 sink, which has increased since 1990, even after CO2 emissions from other land-use changes that release carbon are subtracted. In the ‘50s and ‘60s major tree planting campaigns led to a growing forest biomass over the last decades (some 70% of the carbon is contained in the soil). On the other hand, more land-use for infrastructure such as buildings and roads, and new agricultural land, such as draining of swamps, have contributed to emissions of GHG. Altogether, the net removal (the sink) of GHG from forest and other land-use was estimated at 20 million tonnes of CO2e in 2020.

In Sweden, GHG emissions from the agricultural sector were 6.7 million tonnes in 2021. The emissions, which mainly consist of methane and nitrous oxide from animal feed digestion, manure handling and nitrogen conversion in agricultural land, have remained at about the same level since 2005 but have decreased by 13% since 1990.

Agriculture's emissions from the use of fossil fuels in tractors and other work machinery, fossil fuels for heating premises, for stationary equipment such as grain dryers and changes in carbon stocks linked to agricultural land use are reported in other sectors.

During the period 1990–2021, the land-use sector reported an annual net removal of between 35 and 50 million tonnes of CO2e, with a decreasing trend in the last decade mainly linked to a reduced growth in living biomass on forest land. According to the tightened LULUCF regulation, the net removal in the Swedish LULUCF sector must end up at a level that is approximately 4 million tonnes of CO2e higher in 2030 compared to the average level during the base period (2016–2018), which means a total net removal of 44 million tonnes in 2030.

The largest net removals occur through the storage of carbon dioxide in trees on forest land (25 million tonnes in 2021), mineral soil (16 million tonnes in 2021) and the storage of carbon in harvested wood products (9 million tonnes).

The development of net removal is associated with very large uncertainties. A 2023 assessment by Swedish EPA includes four different scenarios for the LULUCF sector, with different assumptions about harvesting levels and biomass growth, illustrating the sensitivity of the results

Naturvårdsverket (2023). Underlag till regeringens kommande klimathandlingsplan och klimatredovisning. NV-08102-22. Retrieved from, https://www.naturvardsverket.se/499a4f/contentassets/4c414b0778e9409fb2836fc4d3dc6259/underlag-till-regeringens-kommande-klimathandlingsplan-och-klimatredovisning-2023-04-13.pdf

The largest net emissions in the LULUCF sector occur from peatlands with drainage ditches on forest land, arable land and land exploited for buildings and infrastructure. Peatlands with drainage ditches on forest and agricultural land are estimated to cause an annual emission of just over 9 million tonnes of CO2e.

15.3. Pathways towards climate neutrality in the agriculture, forestry and other land use sector

Initiatives already implemented for reducing the GHG emissions in the Danish agriculture and forestry sector are limited. Projections from the DEA estimate that the current agreed policies will lead to a reduction of 0.5 million tonnes of CO2e between 2021 and 2030 when implemented. In this projection the agriculture and forestry sector will make up 52% of the expected emissions in 2030

Energistyrelsen (2023, April). Klimastatus og -fremskrivning, 2023. Retrieved from, https://ens.dk/sites/ens.dk/files/Basisfremskrivning/kf23_hovedrapport.pdf

Klimarådet (2023). Sektorvurderinger, Baggrundsnotat til Klimarådets Statusrapport 2023, kapitel 3. Retrieved from, https://klimaraadet.dk/sites/default/files/paragraph/field_download/Baggrundsnotat%20Sektorvurderinger.pdf

The agricultural agreement passed in 2021 contains a strategy to implement a carbon tax for the agricultural sector. The intention to introduce a tax on GHG from agriculture and land-use is included in the Government’s Coalition Agreement, but the concrete design is still to be decided on the grounds of an expert group’s recommendations, which are expected to be presented in the autumn of 2023. The tax is estimated to potentially reduce GHG emissions from the sector by 5 million tonnes of CO2e in 2030. However, as the concrete design of the carbon tax remains unknown, it is not possible to estimate which reduction potentials the tax will realise.

Klimarådet (2023). Sektorvurderinger, Baggrundsnotat til Klimarådets Statusrapport 2023, kapitel 3. Retrieved from, https://klimaraadet.dk/sites/default/files/paragraph/field_download/Baggrundsnotat%20Sektorvurderinger.pdf

With the currently planned policies, the Danish Energy Agency estimates that GHG emission from the agriculture and forest sector are expected to reduce by 31% in 2030 compared to 1990 levels. This leaves a 24-34 percentage points residual in order to reach the 2030 target of 55-65% reduction

Energistyrelsen (2023, April). Klimastatus og -fremskrivning, 2023. Retrieved from, https://ens.dk/sites/ens.dk/files/Basisfremskrivning/kf23_hovedrapport.pdf

The Climate Council finds the current policies and strategies highly inadequate and untimely if Denmark is to reach its reduction targets for the agriculture and forestry sector. The Council estimates that implementation of further policies with a reduction potential of 5.4 million tonnes of CO2e are needed in order to meet the 2030-target of 55-65% reduction

Klimarådet (2023). Sektorvurderinger, Baggrundsnotat til Klimarådets Statusrapport 2023, kapitel 3. Retrieved from, https://klimaraadet.dk/sites/default/files/paragraph/field_download/Baggrundsnotat%20Sektorvurderinger.pdf

The reduction potential of 5 million tonnes of CO2e from the strategies of the agricultural agreement are assessed to be sufficient to meet the overall target of 70% GHG emission reduction in 2030.

The Climate Council consider the strategies to be based on immature technologies and to be limited by several political conditions, in particular that the business sectors competitive capacity must not be reduced

Møllgaard, P., Jacobsen, J.B., Kristensen, N.B., Elmeskov, J., Halkier, B., Heiselberg, P., Knudsen, M.T., Morthorst, P.E. & Richardson, K. (Febuary 2023). Statusrapport 2023. Klimarådet. Retrievde from, https://klimaraadet.dk/sites/default/files/node/field_file/Klimaraadet_statusrapport23.pdf

Furthermore, even if Denmark’s national targets for GHG emission reduction in the agriculture and forest sector are met, the reductions are inadequate for meeting Denmark’s EU commitments. The DEA estimates a residual need for emissions reduction of around 9 million tonnes of CO2e in the period 2026-2029, and 2 million tonnes of CO2e in 2030 in terms of the LULUCF-commitment. In terms of the Effort Sharing Regulation, the DEA estimates a residual need for emissions reduction of around 16 million tonnes of CO2e in the period 2021-2030.

Energistyrelsen (2023, April). Klimastatus og -fremskrivning, 2023. Retrieved from, https://ens.dk/sites/ens.dk/files/Basisfremskrivning/kf23_hovedrapport.pdf

In 2021, the then Finnish Government agreed a 29% reduction target for agricultural emissions by 2035 (-4.6 million tonnes of CO2e), compared to 2019 (when emissions totaled 16 million tonnes of CO2e).

Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (2023, May 5). Government Report on the Climate Plan for the Land Use Sector. Retrieved from, https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/164927/MMM_2023_12.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Ympäristöministeriö Helsinki (2022). Ilmastovuosikertomus 2022. Retrieved from, https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/164392/YM_2022_24.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

The Climate Change Plan for the Land Use Sector (LULUCF) sets a target for a net carbon sink to be at least -21 million tonnes of CO2e per year for Finland to reach carbon neutrality by 2035.

Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (2023, May 5). Government Report on the Climate Plan for the Land Use Sector. Retrieved from, https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/164927/MMM_2023_12.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke) (2023, March 15). Kasvihuonekaasuinventaario 2021: Maataloussektorin ja maankäyttösektorin nettopäästöihin ei merkittäviä muutoksia verrattuna joulukuussa 2022 julkaistuihin ennakkotietoihin. Retrieved from, https://www.luke.fi/fi/seurannat/maatalous-ja-lulucfsektorin-kasvihuonekaasuinventaario/kasvihuonekaasuinventaario-2021-maataloussektorin-ja-maankayttosektorin-nettopaastoihin-ei-merkittavia-muutoksia-verrattuna-joulukuussa-2022-julkaistuihin-ennakkotietoihin

Finland's sink challenge, i.e. increasing the LULUCF net sink and creating technological sinks, is significant. The net sink would need to be increased by at least 19 million tonnes by 2035 compared to the 2021 level. The land-use sector’s climate plan (MISU) strengthens the sink by an estimated 5 million tonnes. The difference to the sink target, 14 million tonnes, would have to be implemented with additional measures. Cost-effectiveness would justify the reduction of soil emissions from agriculture, the reduction of forest loss to a minimum and the increase of continuous cover forest management on peatland forests, where it is suitable in order to reduce the need for maintenance of the ditch network.

Even if these measures were implemented, there would remain a significant gap, according to a preliminary estimate, of about 8 million tonnes. The net sink gap could be filled by regulating the amount of logging, which immediately increases the LULUCF net sink. In addition, a complementary option is to produce negative emissions from biogenic flue gases with the help of technological sinks. The state can encourage the reduction of felling of forests either by applying measures to reduce supply (e.g. amendments to the Forestry Act and positive incentives to extend the cycle time) or to regulate demand (e.g. a carbon tax on the use of wood or an emissions trading system). Voluntary contractual arrangements between the state and the forest industry are also possible

The Finnish Climate Change Panel. (2023). Suuntaviivoja Suomen ilmastotoimien Tehostamiseen. Retrieved from, https://www.ilmastopaneeli.fi/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/ilmastopaneelin-julkaisuja-1-2023-suuntaviivoja-ilmastotoimien-tehostamiseen.pdf

In Iceland, the overall strategy for mitigation in the agricultural sector is to enable farmers to reduce the climate footprint in all of their operations, to improve data collection and to enhance research in efforts that reduce emissions, such as improved feed or use of fertilisers. The climate action plan includes five initiatives geared towards agriculture: climate friendly agriculture which aims at helping farmers reduce emissions from their own operations, including sequestration, carbon neutral beef production, increased domestic vegetable production, improved handling of fertilisers and improved feeding of livestock to reduce enteric fermentation. Four of the five initiatives are implemented, but the action “improved feeding of livestock” has gone through preliminary testing. According to the Environmental Agency the results from these tests are not promising

Helgadóttir, Á.K., Einarsdóttir, S.R., Keller, N., Helgason, R., Ásgeirsson, B.U., Helgadóttir, I.R., Barr, B.C., Hilmarsson, K.M., Thianthong, J.C., Snorrason, A., Tinganelli, L. & Þórsson, J. (2023, March 15). Report on Policies, Measures, and Projections. Projections of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Iceland until 2050. Environment Agency of Iceland. Retrieved from, https://ust.is/library/Skrar/loft/NIR/0_PaMsProjections_Report_2023_WITH%20BOOKMARKS.pdf

The strategic focus in the climate action plan is to emphasize mitigation and sequestration in the LULUCF sector beyond specific baseline emissions, acknowledging the physical difficulty in transforming the sector to a net negative state. In this regard, the climate action plan defines 6 actions related to the sector that are all being implemented. The actions are: enhanced planting efforts in forestry that are to be enhanced further in 2025; expanding revegetation efforts; restoration of wetlands; wetland conservation; improved mapping of grazing land and land-use; and improved bookkeeping. Efforts in soil reclamation/revegetation have shifted towards reclaiming key native ecosystems such as birchwood and wetlands. National plans for forestry and land/soil reclamation have been devised and benchmarks for sustainable land-use are being introduced. However, setbacks have been experienced in wetland restoration as GHG credits created are not formally certified by third party. Changes in the expected reduction in net emissions from the LULUCF sector in 2030 and 2040, according to the Environmental Agency

Helgadóttir, Á.K., Einarsdóttir, S.R., Keller, N., Helgason, R., Ásgeirsson, B.U., Helgadóttir, I.R., Barr, B.C., Hilmarsson, K.M., Thianthong, J.C., Snorrason, A., Tinganelli, L. & Þórsson, J. (2023, March 15). Report on Policies, Measures, and Projections. Projections of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Iceland until 2050. Environment Agency of Iceland. Retrieved from, https://ust.is/library/Skrar/loft/NIR/0_PaMsProjections_Report_2023_WITH%20BOOKMARKS.pdf

Norway has some programmes where farmers can get support for environmental measures to increase biodiversity on their land. In 2020 a new law that prohibited cultivation of swamps for agricultural purposes was adopted. In 2019 the farmers’ federations made a broad agreement with the government to reduce GHG emissions by 5 million tonnes of CO2 by 2030, including GHG emissions related to land-use changes, transportation and energy use. The most important measures are improved animal feed and breeding practices in addition to carbon storage, such as through biochar use. The government will also support measures to change peoples’ diet in a more climate-friendly direction. There are fewer plans after 2030, but more attention given to self-sufficiency and sustainability challenges. This includes changing crops to more cereals and legumes and using more land for grazing. The dependency on soy imports for animal feed will be reduced.

In recent years, nature restoration has gained more attention. Additional measures to safeguard more carbon storage and nature conservation benign forestry practices are planned.

Klima- og miljødepartementet (2022, October 16). Særskilt vedlegg til Prop. 1 S (2022–2023), Regjeringas klimastatus og -plan. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/fad4e2d774cf45ac8ad0e8cbb1ea093f/no/pdfs/kld_regjeringas_klimastatus_og_-plan.pdf

There are currently relatively few policy instruments in Sweden that directly aim to reduce GHG emissions in the agricultural sector. The most central management takes place via the EU's common agricultural policy. For the 2014–2020 programme period in Sweden (which was extended until 2022) support has gone mainly to the environmental area, aimed at biological diversity and preservation of landscape.

Similarly, there are few policy instruments that aim to directly effect emissions and uptake in the LULUCF sector in Sweden. EU legislation is having an increasing impact on land use in Sweden, and the LULUCF sector is of great importance for both Sweden's and the EU's goals for climate and biodiversity to be reached. The European Commission’s proposal for a new regulation on nature restoration may impose additional requirements, including passive restoration of forest land and rewetting of agricultural land on drained peatland.

Support for increased carbon storage in agricultural land via the EU's common agricultural policy and within the so-called wetlands initiative, which is mainly carried out within the local nature conservation initiative but also through special funds being transferred to the Swedish Forestry Agency, is the policy instrument that has been introduced in Sweden so far with the clear objective of contributing to a reduced climate impact. In addition, there is also relatively extensive regulation in The Forestry Act which indirectly affects uptake of carbon dioxide and the release of greenhouse gases in the LULUCF sector.

The current CAP program period applies to 2023–2027. In the strategic plan for the new period, Sweden has also partially prioritised measures to strengthen the environmental and climate focus in line with the EU's higher ambitions in the area. The new orientation involves, inter alia, the introduction of new one-year environmental and climate support for intermediate crops for increased carbon storage. Designated funds for investments in measures that reduce emissions of ammonia from manure management were introduced, that can also reduce nitrous oxide emissions.

Outside of the strategic plan, it is also possible for farmers to apply for support for investment to produce biogas based on manure which leads to reduced emissions of methane mainly, but also of nitrous oxide. There is also production support. More and more biogas is produced from manure and the increase is projected to continue

Naturvårdsverket (2023). Underlag till regeringens kommande klimathandlingsplan och klimatredovisning. NV-08102-22. Retrieved from, https://www.naturvardsverket.se/499a4f/contentassets/4c414b0778e9409fb2836fc4d3dc6259/underlag-till-regeringens-kommande-klimathandlingsplan-och-klimatredovisning-2023-04-13.pdf

The latest projections indicate that emissions from the agricultural sector will decrease slightly as a result of, inter alia, a reduced number of livestock and reduced cultivated area

Naturvårdsverket (2023). Underlag till regeringens kommande klimathandlingsplan och klimatredovisning. NV-08102-22. Retrieved from, https://www.naturvardsverket.se/499a4f/contentassets/4c414b0778e9409fb2836fc4d3dc6259/underlag-till-regeringens-kommande-klimathandlingsplan-och-klimatredovisning-2023-04-13.pdf

15.4. Challenges on the way towards climate neutrality and opportunities for Nordic collaboration

In Denmark, worries about beef and dairy production moving abroad is a major challenge. If demand for beef and dairy remains high or increases, a decrease in production in Denmark will have a leakage of production and thus GHG emissions. However, GHG emissions from agriculture, including beef and dairy, must decrease while productivity increases in order to achieve the Paris Agreement and securing food for a growing population.

Furthermore, net emissions from land-use were 5.1 million tonnes in 2021, mostly from cultivating wetlands. As a part of the agricultural agreement from 2021, it was decided to take 100,000 ha wetlands out of production. The DEA expects emission from land-use to decrease by 1.4 million tonnes from 2021-2030, which is driven mainly by taking wetlands out of production. However, this process of taking out wetlands has proven to be more difficult and slower to implement than planned.

Klimarådet (2023). Sektorvurderinger, Baggrundsnotat til Klimarådets Statusrapport 2023, kapitel 3. Retrieved from, https://klimaraadet.dk/sites/default/files/paragraph/field_download/Baggrundsnotat%20Sektorvurderinger.pdf

Emission reductions in Finnish agriculture face several challenges. Finnish agricultural production is predicted to remain the same as today or, with growing climate impacts, increase, as production may shift to Northern Europe. On the other hand, agriculture suffers from low profitability, which makes the take-up of new measures by farmers less probable.

Another challenge is that in some parts of the country organic peatland soils are very common and some farms are almost entirely on organic land. This makes it difficult to reduce the number of peatlands under cultivation. The structural change going on in Finnish agriculture leads to larger animal farms and regional concentration of animal production. For example, the number of cows on a milk farm has increased by 5-6% per year

Lehtonen, H., Saarnio, S., Rantala, J., Luostarinen, S., Maanavilja, L., Heikkinen, J., Soini, K., Aakkula, J., Jallinoja, M., Rasi, S., Niemi, J. (2020). Maatalouden ilmastotiekartta – Tiekartta kasvihuonekaasupäästöjen vähentämiseen Suomen maataloudessa. Maa- ja metsätaloustuottajain Keskusliitto MTK ry. Helsinki. Retrieved from, https://www.mtk.fi/documents/20143/310288/MTK_Maatalouden_ilmastotiekartta_net.pdf/4c06a97a-c683-1280-65ba-f4666132621f?t=1597055521915

Livestock production accounts for almost 90% of the agricultural emissions (excluding land-use and energy emissions). Reducing livestock emissions is thus one of the main challenges for the agricultural sector to contribute to climate targets. Without major technological breakthroughs, a substantial GHG reduction will require a reduction in livestock production

Møllgaard, P., Jacobsen, J.B., Kristensen, N.B., Elmeskov, J., Halkier, B., Heiselberg, P., Knudsen, M.T., Morthorst, P.E. & Richardson, K. (Febuary 2023). Statusrapport 2023. Klimarådet. Retrievde from, https://klimaraadet.dk/sites/default/files/node/field_file/Klimaraadet_statusrapport23.pdf

Lastly, there is a huge challenge in increasing the net sink of the LULUCF sector. 2021 was a turning point as the LULUCF sector became a net source rather than a net sink. Significant additional measures would be needed to regain the sink potential to meet the target set in the Climate Change Plan, but the political acceptability of the required steps is contested.

Iceland aims to significantly increase mitigation and sequestration in this sector by reducing emissions and enhancing sequestration. Emissions, however, dwarf sequestration which are in part legacy effects from former land management in the country. Coordinated plans in forestry and land restoration/revegetation acknowledge the need for careful planning, biodiversity protection and focus on restoring wetlands and native vegetation such as birch. The challenges to ensure effective mitigation and sequestration in the LULUCF sector include: i) effective engagement with landowners: such engagement is needed to ensure effective restoration of wetlands and improved grazing conditions for livestock; ii) possible impact on biodiversity from forestry and land-reclamation plans; iii) lack of formal third-party certification of avoided GHGs from wetland reclamation plans; iv) lack of baseline and monitoring data: to ensure effective mitigation and sequestration and to enable certification of efforts, enhanced nationwide baseline and monitoring data collection is needed.

The pathway for the agricultural sector towards lower emissions is challenging and will require simultaneous change in diets and reduction of livestock. This creates significant challenges, including: i) the impact on rural development and farming communities, ii) the need to safeguard food security and iii) emissions leakage as domestic self-sufficiency in meat and dairy production could be challenged.

For Norway, the main challenges for climate change mitigation for agriculture are scarce availability of high-quality land as well as arduous climate conditions for agriculture production. A large share of agricultural land is only suitable as grazing land for sheep and cattle, generating a sizeable methane emission given ruminants’ digestion system. Reducing imports of animal feed can reduce sustainability concerns in exporting countries and increase self-sufficiency but may lead to more methane emissions. Norway spends substantial public money on various support arrangements for agriculture (e.g. through negotiated prices on agricultural products and tariffs on competing imports). Support for farmers is also motivated by the importance of agriculture for rural settlements and for preserving culture landscapes.

The net CO2 sink of Norway’s forested areas is, for the time being, large but will be substantially reduced over the next decades due to aging trees. Avoiding many forest areas going from a CO2 sink to source is doable but will require large and long-term programs of afforestation to replace old trees and harvested wood.

There is a need for more measures in the agricultural sector in Sweden to enable the sector to contribute to reaching the climate targets for 2030 and 2045

Naturvårdsverket (2023). Underlag till regeringens kommande klimathandlingsplan och klimatredovisning. NV-08102-22. Retrieved from, https://www.naturvardsverket.se/499a4f/contentassets/4c414b0778e9409fb2836fc4d3dc6259/underlag-till-regeringens-kommande-klimathandlingsplan-och-klimatredovisning-2023-04-13.pdf

The main challenges in reducing emissions in agriculture are that they are difficult to measure, trade-offs with other environmental objectives, consideration of food security, as well as the sector's exposure to international competition and the risk of emission leakage. The challenges mean, among other things, that it can be difficult to introduce policies that target sources of emissions directly

Swedish Environmental Protection Agency and Swedish Board of Agriculture. (2022). Jordbrukssektorns klimatomställning. Rapport 7060. Retrieved from, https://www.naturvardsverket.se/publikationer/7000/978-91-620-7060-1/

EU legislation is having an increasing impact on land use in Sweden, and the land-use sector is of great importance for achieving Sweden's and the EU's goals for climate and biodiversity. With regards to LULUCF, how the state, through various policy instruments, can ensure that the market allocates the forest resource in order to achieve the greatest possible societal benefit

Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Swedish Forest Agency, and Swedish Board of Agriculture. (2022). Förslag för ökade kolsänkor i skogs- och jordbrukssektorn. Rapport 7059. Retrieved from, https://www.naturvardsverket.se/publikationer/7000/978-91-620-7059-5/.

Across the Nordic countries, only small emission reductions have been achieved in the agricultural sector and strategies and initiatives are hard to implement due to political concerns such as carbon leakage, regressive effects, food security and rural development. This proves to be a major challenge in decarbonising the sector. A closely connected cross-Nordic issue for forestry and land-use, is the taking out of organic soils, peatlands and wetlands. Rewetting these areas, despite plans in place in some of the Nordic countries, has proven difficult and with much slower progress than originally envisioned. Furthermore, a combination of climate change, demand for land for growing farms and an increased demand for biomass is challenging the forest sinks in the Nordic countries.

Below, we have focused on two main cross-Nordic challenges for the agriculture, forestry and land-use sector:

- addressing emissions from organic soils and securing a future net removal in LULUCF

- transforming the agricultural sector in the Nordic countries.

These are described in further detail below.

15.4.1. Addressing emissions from organic soils and securing a future net removal in the LULUCF sector

The challenge

There is a cross-Nordic challenge in reducing emissions from LULUCF, but also in strengthening the sink potential in this sector. This includes reducing emissions from degraded wetlands, such as cultivated peatlands and improving the sink potential of forests.

Restoring degraded wetlands is a large challenge in many of the Nordic countries, in particular Denmark, Sweden and Finland, where reducing emissions from cultivated peatlands requires giving up agricultural land.

In Finland, since the farmed organic soils are geographically clustered, this makes taking the areas out of production politically sensitive, and with potential adverse regional social consequences. In Denmark, the goal of taking out 100,000 ha of peatland has also been challenging, taking longer than expected

Klimarådet (2023). Sektorvurderinger, Baggrundsnotat til Klimarådets Statusrapport 2023, kapitel 3. Retrieved from, https://klimaraadet.dk/sites/default/files/paragraph/field_download/Baggrundsnotat%20Sektorvurderinger.pdf

Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (2023, April 6). National Inventory Report Sweden 2023. Retrieved from, https://unfccc.int/documents/627663

In Sweden, Norway and Finland, forests play an important role as carbon sinks. However, there has been a decrease in the sink potential in both Sweden and Finland. In Sweden this is mainly due to changing weather conditions (droughts, storms) and insect infestations, and in Finland to increased logging. Furthermore, Norway also expects a decrease in the sink due to aging trees with lowering sequestration potentials. This poses a challenge in terms of using this sector to balance out emissions in the future.

Opportunities

- Knowledge sharing and research co-operation on addressing emissions from organic soils

This research could include investigations into the climate benefit of restoring wetlands, providing important knowledge for future political decisions and prioritisation of efforts. It could also cover the cost-efficiency and social acceptability of various policies to address organic soil emissions.

The research could further be expanded to alternatives to conventional farming on peatlands, e.g. paludiculture.

15.4.2. Transforming the agricultural sector in the Nordic countries

The challenge

Reductions in emissions from the agricultural sector is, as mentioned earlier, a challenging task, due to concerns about food security and growing demand from a growing global population. Across all Nordic countries there is a challenge in reducing emissions from agriculture on a farm level, in terms of emissions from handling manure, methane emissions from livestock and crop cultivation.

So far, technical solutions to the challenges listed above have been the main focus in the abatement of emissions from agriculture across the Nordic countries

Nordic Council of Ministers (2021, June 23). Nordic Food Transition, Low emission opportunities in agriculture. Retrieved from, https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1571866/FULLTEXT03.pdf

In many of the Nordic countries, livestock production accounts for a big portion of the GHG emissions in the agricultural sector due to their methane emissions. For example, in Finland, livestock production accounts for almost 90% of the agricultural emissions (excluding land-use and energy emissions). So far, there has been little development in decreasing these emissions besides increasing the productivity of the animals.

In recent years, more attention has been given to combining technical efforts with consumer-based dietary shifts, but policies are still lacking in this area across the Nordic countries. One of most promising ways to address the climate challenges in the agricultural sector is replacing the consumption of animal-based food with plant substitutes such as legumes, grains, algae and vegetables

Nordic Council of Ministers (2021, June 23). Nordic Food Transition, Low emission opportunities in agriculture. Retrieved from, https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1571866/FULLTEXT03.pdf

Opportunities

- Knowledge sharing on carbon pricing in agriculture – risks and incentive structures

- Nordic research on climate accounting on farms and improving knowledge on ways to reduce emissions on the farm from livestock, such as manure management – including biogas production, crop cultivation and fodder additives to reduce methane releases from ruminants

- Studies on examples on how to improve the conditions for producers of plant-based proteins, both in terms of research, education and regulatory frameworks

The recommendations above have also previously been recommended in Nordic Food Transition: Low Emissions Opportunities in Agriculture (2021)

Nordic Council of Ministers (2021, June 23). Nordic Food Transition, Low emission opportunities in agriculture. Retrieved from, https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1571866/FULLTEXT03.pdf

- Target Nordic research and innovation funds towards plant-based production