Executive summary

Plastics are used in a wide range of applications across the world due to their high versatility, durability and relatively low cost. The use of plastics can also reduce GHG emissions by, for example, extending food shelf life or reducing the weight of vehicles. However, the plastic industry has not borne the cost of plastic externalities; on the contrary, it has benefited from public subsidies, for example in regards to oil exploration.

1. Bauer, F. et al. (2023). Petrochemicals and climate change: Powerful fossil fuel lock-ins and interventions for transformative change

The objective of this report is to define a package of far-reaching policies and estimate how, if implemented globally and concurrently, this could minimise the impacts of mismanaged plastics and plastic releases into the environment, including microplastics, by 2040. Two scenarios – the Business-as-Usual Scenario (current trajectory) and the Global Rules Scenario – are presented to depict two possible states of the plastic system by 2040. The Global Rules Scenario represents a future in which common global rules based on the international legally binding instrument would trigger a far-reaching package of policy interventions across the plastic lifecycle, adopted in all geographies. The analysis estimates the impact of these policy interventions on plastic stocks and flows, as well as on environmental, economic, and social implications. These policy interventions are not presented as the only set of policies that could achieve similar outcomes. Instead, the Global Rules Scenario simply models a package of far-reaching policies to showcase the level of reach needed to make a significant impact.

This section presents the report’s main insights from the modelled scenarios:

Business-as-Usual Scenario

Without global action, the annual levels of mismanaged plastics would continue to rise and could almost double from 110 million tonnes (Mt onwards) in 2019 to 205 Mt by 2040, an 86% increase. Annual production of virgin plastics would increase from 430 Mt in 2019 to 712 Mt by 2040, a 66% increase. GHG emissions from the plastic system could further increase from 1.9 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) per year in 2019 to 3.1 GtCO2e by 2040, an increase of 63%. This trajectory is incompatible with the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement.

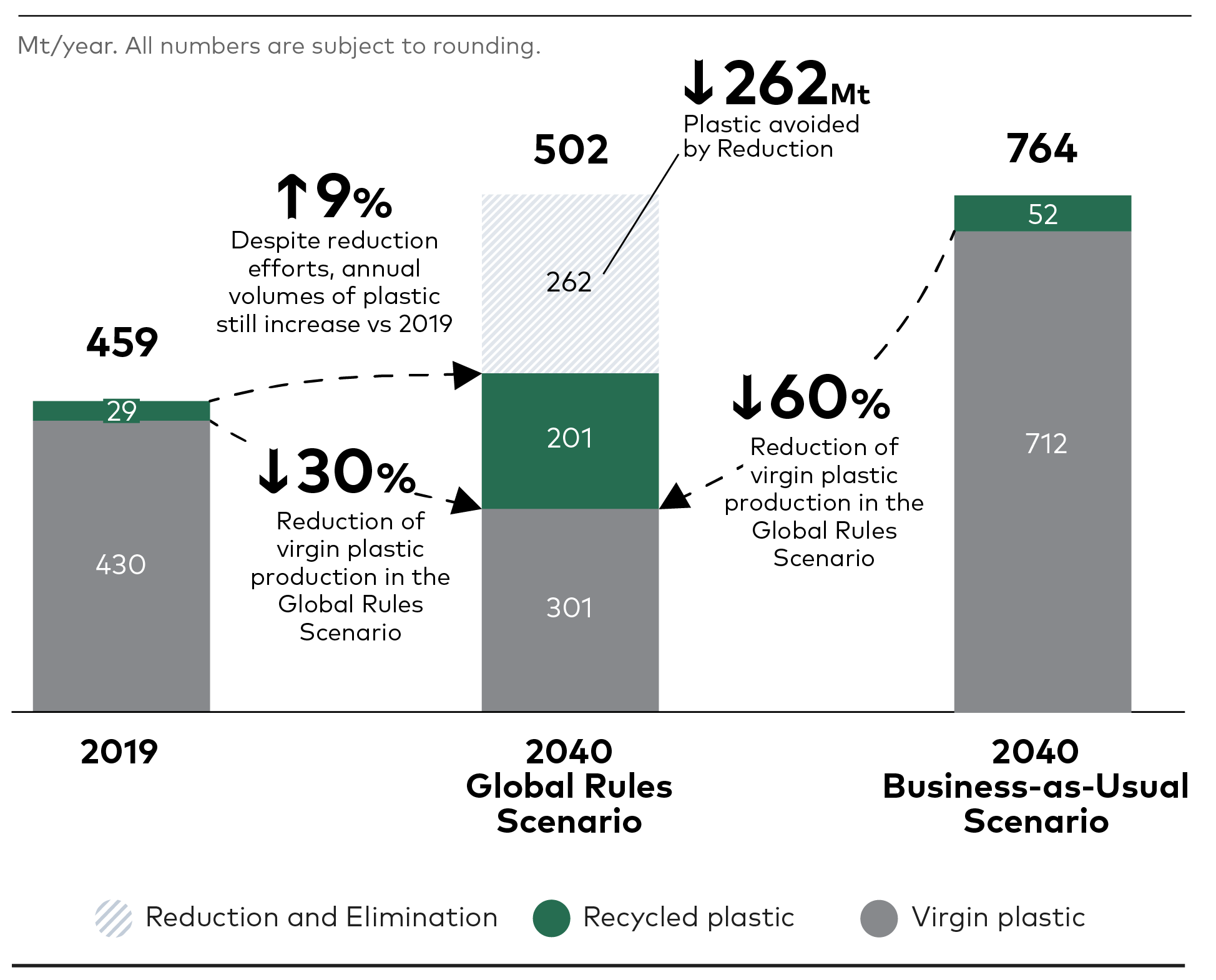

The world produced ~460 Mt of plastics (430 Mt estimated to be virgin and 29 Mt recycled) and generated 385 Mt of plastic waste

Plastic waste, in the context of this report, encompasses any plastic volume that has ended its use-phase or that has been lost or released during any other phase. This would include any plastic no longer in use-phase, microplastic releases, mismanaged pellets, or loss of fishing / aquaculture gear.

In the Business-as-Usual Scenario, the annual volume of plastics entering the system could rise from 460 Mt in 2019 to 764 Mt by 2040 (712 Mt virgin and 52 Mt recycled). As production and consumption increase, annual plastic waste generation could grow from 385 Mt in 2019 to 646 Mt by 2040. This trend is driven by population and consumption growth, which are also proportionally higher in regions that currently lack the necessary resources and infrastructure to manage waste, thus exacerbating the consequences of an already flawed plastic system over time.

FAST FACTS

↑ 86%

increase in annual mismanaged plastic volumes by 2040

(Business-as-Usual relative to 2019)

↑ 66%

increase in annual virgin plastic production by 2040

(Business-as-Usual relative to 2019)

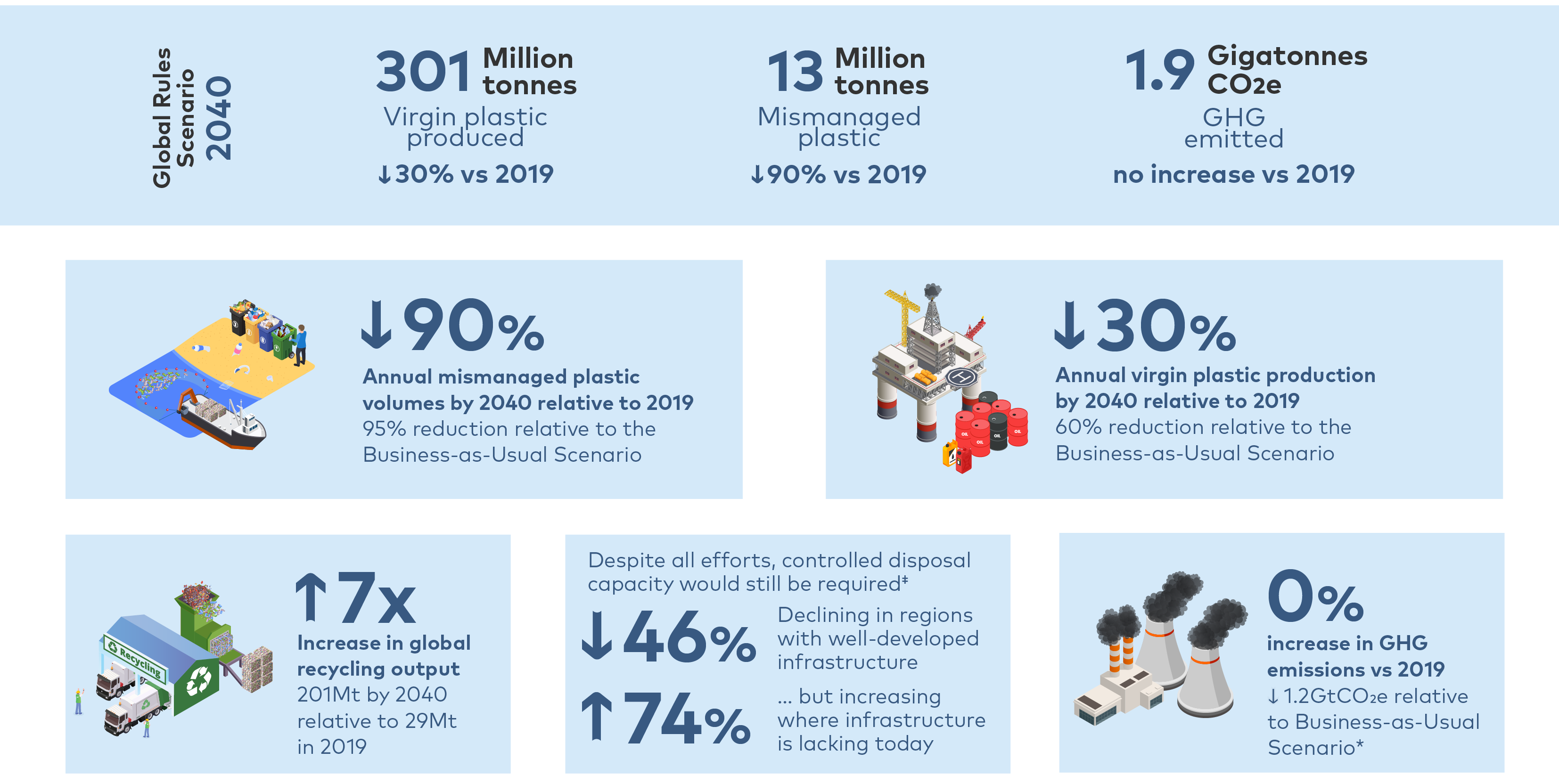

Global Rules Scenario

A set of far-reaching policies across the plastic lifecycle, adopted globally, could reduce annual mismanaged plastic volumes in 2040 by 90% relative to 2019. This set of policies would reduce annual volumes of virgin plastic production in 2040 by 30% relative to 2019. A reduction of this level would be needed to address the issue of mismanaged plastics through solutions across the plastic lifecycle, rather than simply expanding waste management.

The Global Rules Scenario would reduce annual volumes of virgin plastic production and consumption by applying targets, fees and demand reduction policies; eliminating avoidable single-use plastics on certain applications; mandating substitution where alternative materials would yield better impacts; and expanding safe reuse, recycling, durability and repair. By 2040, annual virgin plastic production would decrease by 30% relative to 2019 levels, equivalent to a 60% reduction relative to the 2040 levels in the Business-as-Usual Scenario. When counting both virgin and recycled plastics, annual production by 2040 would still result in an increase of 9% relative to 2019 levels (with a significant increase in the share of recycled plastics), as expected population and consumption growth outpaces reduction levers in some regions. Figure 1 below displays these results.

↓ 90%

reduction in annual mismanaged plastic volumes by 2040

(Global Rules Scenario relative to 2019)

↓ 30%

reduction in annual virgin plastic production by 2040

(Global Rules Scenario relative to 2019)

FIGURE 1

Annual plastic production under the Business-as-Usual and Global Rules Scenarios

The Global Rules Scenario would result in a 30% reduction in annual virgin plastic production by 2040 relative to 2019 levels.

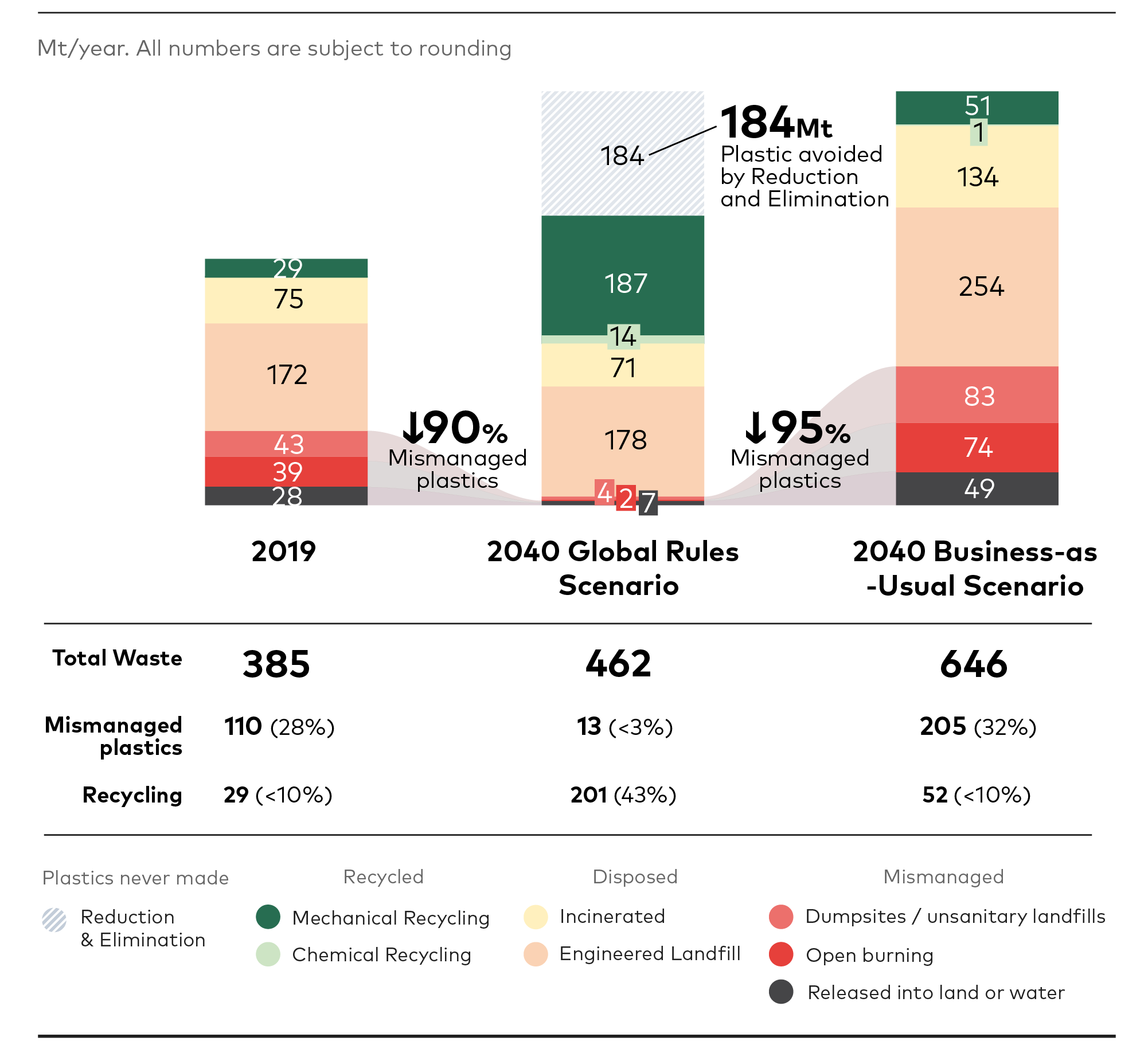

The Global Rules Scenario would prevent 184 Mt of plastic waste annually by 2040. These policies could also result in an increase in recycling output to 201 Mt by 2040, relative to 29 Mt in 2019. This is equivalent to global recycling output increasing sevenfold by 2040. However, to achieve these results, the policy package laid out in the Global Rules Scenario would need to be implemented across all jurisdictions. If some large countries did not engage in this level of adoption, the result would significantly worsen.

Despite the scale-up of reduction and recycling, some plastic waste still would not be prevented or recycled. This volume is estimated in the Global Rules Scenario at 249 Mt of plastic waste in 2040, which would thus be subject to controlled disposal.

Controlled disposal prevents plastic waste from being mismanaged and includes engineered landfills (but not dumpsites), incineration with energy recovery and plastic-to-fuel technologies.

The annual volumes of mismanaged plastics in 2040 would decrease by 90% relative to 2019 levels and by 95% relative to the 2040 levels in the Business-as-Usual Scenario. However, 13 Mt of mismanaged plastics would remain annually by 2040, with 4 Mt ending up in dumpsites, 2 Mt burned in the open and 7 Mt released into land or water. Out of these 7 Mt released into land and water environments, microplastics would represent 5 Mt. Figure 2 below displays these results.

x7

increase in global recycling output by 2040

(relative to 2019)

Plastic volumes ending in controlled disposal

(2040 Global Rules Scenario relative to 2019)

↓ 46%

Declining in regions with well-developed infrastructure

↑ 74%

… but increasing where infrastructure is lacking today

FIGURE 2

End of Life fate of plastic waste in 2019 and 2040 in the Business-as-Usual and Global Rules Scenario

The Global Rules Scenario would result in a 90% reduction in annual mismanaged plastic volumes relative to 2019 levels

The Global Rules Scenario would result in an estimated 1.9 GtCO2e per year by 2040, which is equivalent to 2019 levels but would represent a mitigation of GHG emissions from the global plastic system of 40% relative to the 2040 levels in the Business-as-Usual Scenario (3.1 GtCO2e). This decline in the Global Rules Scenario compared with the Business-as-Usual Scenario would mainly be driven by a decline in virgin plastic production. To achieve full alignment with the Paris Climate Agreement, further reduction in virgin production or additional decarbonisation levers would be needed beyond the reduction and circularity expansion outlined in the Global Rules Scenario.

~ 0%

increase in GHG emissions by 2040

(Global Rules Scenario relative to 2019)

A key driver to reduce plastic production and consumption is a shift away from single-use plastics

The results in the Global Rules Scenario would be achieved through a package of 15 far-reaching policy interventions across the plastic lifecycle, structured across five pillars. The set of policies selected draws on submissions from UN member states and other organisations ahead of INC-2, interviews and open consultations. The next infographic summarises these results and presents the policy interventions. This report’s approach to determining the scale of each pillar is discussed in the report (see Box 5).

The Business-as-Usual Scenario would lead to a substantial increase in plastic production, mismanaged plastics and GHG emissions

The Global Rules Scenario involves 15 global policy interventions

Assumed to be legally-binding, concurrent, implemented across all regions, and across the plastic lifecycle:

The Global Rules Scenario would result in…

‡The Global Rules Scenario would result in controlled disposal (landfill and incineration) decreasing by 2040 relative to 2019 levels in regions that currently have well-developed waste management infrastructure. However, in regions currently lacking infrastructure, despite all efforts, the scenario would result in increased controlled disposal. * Further intervention is required to meet the targets set by the Paris Climate Agreement.

Reduce virgin plastic production and consumption

A significant reduction in virgin plastic production and consumption would be needed in order to substantially reduce mismanaged plastic levels. The Global Rules Scenario would result in a 30% reduction in annual virgin plastic production by 2040, relative to 2019 – equivalent to a 60% reduction relative to the Business-as-Usual Scenario. This would require policy interventions aimed exclusively at reducing virgin plastic volumes in the system.

The key policy interventions on which Pillar A is based are reduction targets, virgin plastic fees and application-specific demand interventions:

1. Targets to reduce virgin plastic volumes

calibrated by sector and local context

Targets to reduce virgin plastics volumes would signal the level of change needed to industry and governments. The reductions in virgin plastic achieved by 2040 under the Global Rules Scenario would vary geographically. Europe, the USA, Canada, Japan, the Republic of Korea and Oceania would see the highest reductions in consumption, since these regions are starting from high consumption per capita. In these regions, the Global Rules Scenario would result in a reduction in annual virgin plastics use of 51% to 63% by 2040 relative to 2019 levels. Regions such as China and Central and South America would see lower – although still significant – reductions in annual virgin plastics use, of 36% to 39% by 2040 relative to 2019 levels. This is due to lower consumption per capita today and their expected economic and demographic growth. Finally, regions with lower consumption per capita today but high forecasted economic and demographic growth – such as India, South and Southeast Asia, Africa and the Middle East – would see annual virgin plastics demand increase by ranges between 8% and 57% by 2040 relative to 2019 levels. These reductions could be aggregated to a global target, to signal the level of action required and communicate global action under a single objective.

2. Virgin plastic fees to fund solutions across the plastic lifecycle

with fees ranging from $1000 to $2000/tonne by 2040, calibrated by region

Virgin plastic fees to fund solutions across the plastic lifecycle could help to reduce the volume of virgin plastics in the system. This policy would level the playing field, internalise externalities and incentivise shifts away from virgin plastic. The Global Rules Scenario applies fees to virgin plastic volumes entering the system, calibrated by region and increasing progressively. The model follows the OECD’s Global Ambition Scenario in its Global Plastics Outlook: Policy Scenarios to 2060, with adaptations by region and set to 2040. The modelled fees vary from US$500 per tonne to US$1,000 per tonne by 2030, and from US$1,000 per tonne to US$2,000 per tonne by 2040, depending on the region.

3. Application-specific levers to reduce plastic consumption

in textiles, fisheries and aquaculture, transportation and construction

Application-specific levers to reduce plastic consumption are included for certain sectors. For example, for textiles, the Global Rules Scenario assumes a ban on the destruction of overproduced and returned items. This is already underlined in the EU’s Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles,

European Commission. (2022). EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles.

Overseas Development Institute (ODI). (2020). Phasing Out Plastics.

UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme. (2020). Single-use Plastic Bags and their Alternatives: Recommendations from Life Cycle Assessments.

Eliminate avoidable and problematic plastics and chemicals

The Global Rules Scenario would eliminate certain avoidable single-use plastic applications through bans and reuse targets. Avoidable or unnecessary plastics include plastic applications that can be reduced or replaced with non-plastic alternatives or eliminated entirely without undesirable outcomes. In the case of problematic plastics – those which present hazards or risks to human health or biodiversity, or which hinder circularity – global criteria would be required in order to determine which substances should be phased out.

The key policy interventions on which Pillar B is based are bans and reuse targets for single-use applications and phaseout criteria for problematic plastics:

4. Bans on avoidable single-use plastics

to incentivise elimination, shift to reuse models and substitution

Bans on avoidable single-use plastics would shift certain packaging applications to safe multi-serve formats, reuse or refill alternatives; or replace plastic for other materials with superior environmental performance. In the Global Rules Scenario, these bans are applied to a broad range of applications such as single-use plastic bags; food service disposables and takeaway items; pots, tubs and trays for fruit and vegetables; plastics in logistics and business-to-business applications (eg, films to wrap pallets, e-commerce plastics); and multi-material/multi-layer sachets where better alternatives exist. Before banning a single-use plastic application, it would be necessary to run a comprehensive case-by-case analysis that considers the local context to prevent unintended consequences. To this end, product LCAs could be conducted to determine whether the alternatives will improve overall environmental, health and social impacts across their full lifecycle.

Conducting LCAs was not part of this report, which instead leveraged past studies to determine what bans would be applicable and whether the outcome would be elimination, shift to reuse or substitution

5. Reuse targets for avoidable single-use plastics

between 15% to 100%, calibrated by applications

Reuse targets for avoidable single-use plastics would promote the scaling of new delivery models that replace single-use plastic packaging with alternatives that are used across multiple consumption cycles. The Global Rules Scenario leverages similar ranges to those reuse targets discussed under EU Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation drafts,9 for example, assuming reuse targets for 2040 between 15% and 25% for beverages containers (sodas, water, alcohol) and household products (eg, cleaning, personal care). The scenario assumes higher targets than those in the European Union drafts for other categories, for example, 100% for plastics used in logistics and transport packaging. Takeaway food and beverage containers (which also fall within the scope of single-use bans) either would be eliminated or would shift to safe reuse models. These targets would rest with final distributors (retailers and food service providers).

6. Phaseout criteria for problematic plastics, polymer applications and chemicals of concern

including bans and moving to ‘safe lists’ progressively

Problematic plastic products, polymer applications and chemicals of concern would be phased out according to common global criteria encompassing all those that create hazardous conditions, pose a risk to human health or the environment, impede safe reuse or recycling, or have high likelihood of releasing into the environment. For example, for several groups of chemicals used in plastic products (eg, bisphenols, flame retardants and phthalates), there is evidence pointing to human health hazards.

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and Secretariat of the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions. (2023). Chemicals in plastics: a technical report.

USA Plastic Pact. (2021). Problematic and Unnecessary Materials Report.

Kenya Plastic Pact. (2022). Problematic & Unnecessary Plastics Items List.

Expand safe circularity via reuse, durability and recycling

Products would be redesigned to scale safe reuse, durability, repair, and recycling with common design rules, adjusted for local contexts. In the Global Rules Scenario, the world’s recycling output would increase sevenfold by 2040 relative to 2019 levels, requiring collection rates to reach more than 95% globally by 2040 and recycling rates to range between 15% and 67% for specific plastic applications. To support this, extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes would be implemented, with fees designed to operate on a net cost basis towards the development of the necessary infrastructure. These policies could impact the livelihoods of workers in the informal sector, so controls would be required for a just transition.

After reducing the volumes of plastic in the system (Pillars A and B), the Global Rules Scenario prioritises the expansion of circularity in those plastics that remain. The key policy interventions on which Pillar C is based are product design rules, waste collection targets, EPR schemes and protections for the informal sector:

7. Design rules for safe reuse, repair, durability and cost-effective recycling

calibrated by application and by local context

Design rules for safe reuse, durability, repair and cost-effective recycling in local contexts would be introduced under the Global Rules Scenario. These rules should ensure that plastic products in all sectors of the economy are designed for safe reuse and recycling. The rules would differ by plastic application. For example, for packaging, the Global Rules Scenario assumes improvements in sorting and recyclability due to better designs following the Golden Design Rules,

Consumer Goods Forum (CGF). (2021). Golden Design Rules For optimal plastic design, production and recycling.

8. Targets for collection and recycling rates

including segregated collection for plastics

Targets for collection and recycling rates would seek to maximise collection of plastic waste and increase the supply of recycled plastics. The Global Rules Scenario would result in waste collection rates of more than 95% across all geographies for all sectors considered. In low and middle-income countries, substantial development and resources would be needed to reach these levels. Globally aligned targets towards this goal would send an important signal to central governments, local authorities and the private sector.

The Global Rules Scenario prioritises safe mechanical recycling as the main method of recycling (prioritised over chemical recycling), resulting in a global plastics recycling rate of 43% by 2040 (compared to less than 10% in 2019). The Global Rules Scenario would expand recycling infrastructure capacity to 201 Mt globally (compared to 29 Mt in 2019). Chemical recycling technologies are still in development and present drawbacks such as higher energy consumption, lower material-to-material yields, increased GHG emissions and greater investment requirements that could create ‘lock-in’ effects, disincentivising better solutions in the future. For plastic waste that is not suitable for mechanical recycling, the Global Rules Scenario includes limited use of chemical recycling, which would account for approximately 3% of the total plastic waste generated in 2040. Because of the risks and uncertainty associated with chemical recycling, a Global Rules Scenario without chemical recycling was also modelled (see Box 4).

9. Modulated EPR schemes applied across sectors

with fees of $300 - $1000/tonne calibrated by region and by product

Modulated EPR schemes applied across all sectors are applied under the Global Rules Scenario, calibrated by region and product, to promote better designs and fund solutions across the plastic lifecycle. Fees should be defined to account for the costs of infrastructure in the local context, calibrated by application, and should operate on a net cost basis, to incentivise better designs and penalise the use of hard-to-recycle materials or designs. The fees modelled vary per product and region, but range from US$300 per tonne to US$1,000 per tonne by 2040, starting in 2025 and increasing gradually. Common rules within a global framework would also help to harmonise national approaches while still allowing for context-specific adaptation.

UNEP. (2023). Turning off the Tap: How the world can end plastic pollution and create a circular economy.

10. Controls for a just transition for the informal sector

enhancing their labour and human rights

Controls for a just transition for the informal sector would enhance workers’ labour and human rights, as global, national and local interventions – especially the adoption of policies such as EPR and deposit return schemes – could disrupt the livelihoods of these communities. Therefore, the Global Rules Scenario assumes the adoption of these policies to ensure a just and inclusive transition for the informal sector. These should be defined through close collaboration between governments and stakeholders to ensure the inclusion of the informal sector in the waste management system and in relevant policy discussions; and to facilitate the formulation of effective policies to improve incomes and working conditions, and protect the health and human rights of this community.

International Alliance of Waste Pickers. (2023). Recommendations for potential core obligations options for the plastics treaty.

Ensure the controlled disposal of waste that cannot be prevented or safely recycled

Some plastics in use feature intricate designs that can hinder safe recycling, while some plastic waste may not be collected properly segregated to allow for recycling. In these cases, controlled disposal is the last resort to avoid mismanagement. The Global Rules Scenario would result in a 46% reduction in controlled disposal volumes in Europe, the USA, Canada, Japan, the Republic of Korea and Oceania by 2040 relative to 2019 levels. However, in regions

In low, middle and upper-middle income regions in Central, South America and the Caribbean; China; South/Southeast Asia and Eurasia; India; and Africa and the Middle East

The key policy interventions on which Pillar D is based are export restrictions on plastic waste, global standards on controlled disposal and removal programmes for legacy plastic:

11. Restrictions on plastic waste trade

to prevent exports to areas with limited capacity

Restrictions on plastic waste trade would prevent the export of plastic waste to regions with limited capacity or resources. In the Global Rules Scenario, trade restrictions are assumed to expand beyond the Basel Convention to all plastic waste exports, to prevent the transfer of responsibility from advanced waste management systems to underdeveloped systems. Exemptions may exist in the case of shared agreements and small countries and islands without sufficient capacity or scale to develop their own infrastructure.

12. Standards on the controlled disposal of waste that cannot be prevented or safely recycled

as last resort option to prevent plastic mismanagement

Standards on the controlled disposal of waste that cannot be prevented or safely recycled would be fully implemented globally to ensure that waste is not mismanaged. Landfill and incineration are the main options for controlled disposal; with landfills considered preferable in the Global Rules Scenario given lower GHG emissions and costs in comparison to incineration. Incineration of plastics can create ‘lock-in’ effects, as plants require a constant input of plastic waste to provide returns on investment over time, which can disincentivise recycling. Also, there is evidence of negative environmental impacts from incinerators due to inadequate emission controls of pollutants.

Giusti, L. (2009). A review of waste management practices and their impact on human health.

National Research Council. (2000). Waste Incineration and Public Health.

13. Mitigation and removal programmes for legacy plastics in the environment

although still prioritising solutions that prevent releases in the first place

Mitigation and removal programmes for legacy plastic in the environment should be pursued, however the Global Rules Scenario priority is on addressing the root causes of mismanagement and focuses on solutions that prevent releases to the environment in the first place. Removal programmes for legacy plastics would still have a role to play: For example, beach clean-ups are an effective way of raising awareness and may be an enabler for prevention. Data obtained from clean-ups can identify the items that are most likely to end up mismanaged and can inform policy accordingly.

Prevent the use of microplastics and reduce microplastics releases into the environment

An estimated 9 Mt of primary microplastics were released into the environment in 2019; and without effective policy, this figure is projected to increase to 16 Mt by 2040 under the Business-as-Usual scenario. Through a series of policies to prevent the use of microplastics and capture emissions, the Global Rules Scenario would see microplastic releases fall to 5 Mt per year by 2040. Although this represents an important improvement relative to 2019, further solutions and innovation would be required.

The analysis includes primary microplastics from personal care products, pellets, tyre abrasion, paints and textile use; but excludes secondary microplastics.

14. Upstream policies to reduce microplastics use and emissions

through bans, substitution, better product designs, preventive maintenance, and behavioural change

Upstream policies to reduce microplastics use and emissions should be introduced. The analysis assumes microplastics from personal care products are completely eliminated through bans on intentionally added primary microplastics. The model also estimates reduction of microplastics creation and emissions through better designs in textiles and tyres. Finally, the estimate assumes enforcement of a wide range of upstream interventions, such as practices and technologies for the application, maintenance and removal of paints.

15. Downstream policies to capture microplastics, followed by controlled disposal

prioritising capture at source over capture through wastewater treatment systems

Downstream policies to capture microplastics, followed by controlled disposal would avoid the release of microplastics into the environment. The model prioritises capture of microplastics at source, estimating the potential of enforcing certain technologies and industry practices – for example, practices to prevent the release of pellets, microplastic filters in washing machines and paint removal technologies. If capture at source is not possible, the analysis estimates the potential of downstream capture through waste and wastewater systems, although this is left as a last resort option due to requiring substantial infrastructure and investment.

Cost and employment implications

The Global Rules Scenario would yield important savings in public expenditure relative to the Business-as-Usual Scenario. The cumulative[1] public expenditure from 2025 to 2040 in the Global Rules Scenario would total US$1.5 trillion, compared to US$1.7 trillion in the Business-as-Usual Scenario. The savings would mainly accrue from reductions in plastic volumes, resulting in less plastics to collect and manage. However, this would primarily apply to regions with well-developed infrastructure; other regions would still need to invest more in expanding their waste management systems.

US$1.5tn

cumulative public expenditure from 2025 to 2040

(Global Rules Scenario)

The analysis estimates both public expenditure for governments and costs and investments required from the private sector in the Business-as-Usual Scenario and the Global Rules Scenario. Public expenditure in this analysis accounts for the costs of collecting, sorting and disposing of plastic waste. The Global Rules Scenario would result in lower public expenditure relative to the Business-as-Usual Scenario, mainly due to reductions in plastic use, and thus in the volumes to collect and manage.

However, the trends would differ by region. For regions with well-developed infrastructure,

Europe; the USA and Canada; and Japan, the Republic of Korea, New Zealand and Australia.

For regions that currently lack infrastructure,

Central and South America and the Caribbean; China; South/Southeast Asia and Eurasia; India; and Africa and the Middle East.

With regard to employment, it is estimated that both the Business-as-Usual Scenario and the Global Rules Scenario would support 12 million jobs globally by 2040. This suggests that the Global Rules Scenario could be achieved without any decrease in global employment. However, it would require a shift in jobs away from virgin plastic production; a shift in industry towards new business models (eg, reuse) and alternative materials; and improved recycling, collection and waste management systems. Importantly, this transition may not be balanced from a geographical perspective; and it would be essential to put in place controls to ensure a socially just transition, particularly in relation to vulnerable communities.

Priorities for further innovation, research and data

The extent of the issue is such that, even after implementation of the 15 far-reaching policy interventions in the Global Rules Scenario, 13 Mt of plastic would remain mismanaged annually by 2040, requiring further solutions, research, data gathering and innovation.

In the Global Rules Scenario, the impact of the 15 policy interventions is limited by technological, economic and behavioural constraints. By 2040, the scenario would still lack solutions for 13 Mt of annual mismanaged plastic, of which it is estimated that 4 Mt would end in dumpsites, 2 Mt would be burned in the open and 7 Mt would be released into land or water. Out of these 7 Mt released into land and water environments, microplastics would account for 5 Mt; this therefore remains a key area in which solutions are lacking. Innovation would thus be required to improve the design of tyres, paints and textiles to minimise microplastics emissions. The remaining mismanaged plastic volumes would comprise a mixture of all other sectors. To address this, further solutions would need to be incentivised – for example, scaling recycling and collection systems in rural areas of low and middle-income regions to overcome the challenges of remoteness and low population density. Reuse models would require private sector innovation to further reduce costs and GHG emissions. Sorting and recycling technologies should focus on improving yields. Innovation on alternative materials with better impacts and possessing comparable properties to plastic should also be explored.

Further access to information and scientific guidance and research would also be needed. The establishment of a harmonised knowledge base for taking informed action, measuring progress and refining policies would require a globally coherent approach to monitoring and reporting. At present, much of the approach to managing plastics is based on incomplete information, which constrains effective action and the scale-up of solutions. A scientific panel with the appropriate mandate could be instrumental in facilitating such harmonisation.

Paints and tyre abrasion are estimated to be the main sources of microplastic releases

Concluding remarks

To be effective, the 15 policies in the Global Rules Scenario should be complemented by enablers that would close governance and institutional gaps globally, regionally and nationally. These could relate to financial assistance, capacity building, technical assistance and technology transfer, as well as national action plans, national reporting, compliance and periodic assessment and monitoring. The results presented assume that these would be put in place; otherwise, it is unlikely that the assumptions around compliance, enforcement and effectiveness of policies estimated in the analysis could be achieved.

It is clear the current approach to tackling global plastic pollution is not working and incremental policy improvements will be insufficient to solve the problem. While most of the policy interventions proposed in this report would be taken at a national level, unlocking the necessary global adoption and international collaboration would require global rules.

It is also crucial to acknowledge that plastic pollution is a broad problem; and that critical issues such as health risks, chemicals of concern and negative impacts on biodiversity – which are not discussed in detail in this report – must also be addressed. Hence, the Global Rules Scenario is intended merely a starting point for systems change in the global plastics system, rather than as a comprehensive solution.

Yet this report shows that implementing 15 far-reaching policy interventions could take us a long way in the journey towards ending plastic pollution by 2040.

These 15 far-reaching policy interventions could take us a long way towards ending plastic pollution by 2040, requiring further efforts to address it fully