Aerial view of windmills in Pori, Finland.

Photo: iStock

Photo: iStock

Executive Summary

The Council of the EU introduced emergency intervention measures to address high energy prices in October 2022. We describe the implementation of these measures in Denmark, Finland and Sweden and analyse the impact of the measures on the Nordic power market.

Electricity consumption, both during peak hours and in total, was reduced in the winter of 2022–2023 in the three countries. However, we cannot attribute this development solely to the emergency measures. Electricity prices were higher than in previous winters, so it is reasonable to assume that at least part of the reduction is attributable thereto. In addition, the winter was milder than usual. Moreover, it is likely that increased awareness of the situation in the power market also contributed to reducing demand.

The measures targeting electricity producers – the revenue cap in Denmark and Sweden and the profit tax in Finland – do not distort short-term production incentives, though they may distort long-term incentives to invest. To avoid negative impacts on investments, it is important to emphasize that these measures are temporary, one-time measures that were introduced as a response to an extraordinary crisis.

Background and aim of the study

The Council of the EU proposed the Regulation on an emergency intervention to address high energy prices in Europe (hereafter “the CR”) on 14 September 2022. The CR was adopted 6 October 2022 and came into effect 8 October 2022.

The aim of the CR was to mitigate the effects of high energy prices on energy consumers through three exceptional, targeted and time-limited measures:

- Reduction in electricity demand

- Cap on market revenues for inframarginal technologies in electricity generation

- Solidarity contribution from the fossil fuel sector

There was some flexibility in how the measures could be implemented. One aim of this study was to describe how the emergency measures outlined in the CR were implemented in the Nordic countries. Our focus was on Denmark, Finland and Sweden. Iceland and Norway are not EU members and thus did not implement the measures of the CR. Chapter 2 is devoted to a description of the implementation of the measures.

The second aim was to assess the short- and long-term impacts of the measures on the Nordic wholesale power market. The short-term impacts are related to incentives to produce, while the long-term impacts are related to incentives to invest in new capacity. Chapters 3–5 address the impacts of the measures.

Table S.1 summarizes the measures outlined in the CR and how they were implemented in Denmark, Finland and Sweden.

Table S.1. Overview of the implementation of the emergency measures in the Nordic countries

The Council Regulation | Sweden | Denmark | Finland | |

Reduction in electricity demand | Mandatory 5% reduction in electricity consumption during peak load hours between 1 December 2022–31 March 2023. Voluntary 10% reduction of total electricity consumption between 1 November 2022–31 March 2023. Flexible implementation and somewhat flexible definition of peak hours. |

|

|

|

Cap on market revenues | 180 EUR/MWh cap on market revenues obtained from the sale of electricity produced from specific sources between 1 December 2022–30 June 2023. | 180 EUR/MWh cap on market revenues obtained from the sale of electricity produced from specific sources between 1 March 2023–30 June 2023. Tax applied to 90% of hourly realized revenues exceeding the cap. | 180 EUR/MWh cap on market revenues obtained from the sale of electricity produced from specific sources between 1 December 2022–30 June 2023. Tax applied to 90% of monthly realized revenues exceeding the cap. | Additional 30% tax on electricity companies’ profits in 2023 above “ordinary” return on equity. The tax is levied on electricity producers and, under certain conditions, retailers. |

Solidarity contribution from the fossil fuel sector | The fossil fuel sector is levied a tax of 33% on taxable profits that exceed the average profits in the four preceding years by 20%. Applies to fiscal year 2022 and/or 2023. | The fossil fuel sector is levied a tax of 33% on taxable profits that exceed the average profits in the four preceding years by 20%. | The fossil fuel sector is levied a tax of 33% on taxable profits that exceed the average profits in the four preceding years by 20%. | The fossil fuel sector is levied a tax of 33% on taxable profits that exceed the average profits in the four preceding years by 20%. |

Demand reduction measures in the Nordic countries

The Council Regulation stipulated two demand-reduction measures:

- A mandatory 5% reduction in consumption during peak load hours

- A voluntary 10% reduction target in total electricity consumption

One of the key issues the authorities had to determine was which hours should be considered peak load hours. In Sweden, peak load hours were defined as three hours each morning and three hours each afternoon on weekdays. In Finland and Denmark, peak hours were defined as two hours in the morning and two hours in the afternoon on weekdays. The comparison period for the peak hour consumption reduction was the monthly consumption as forecasted by the transmission system operators (TSOs), while the reference period for the total consumption reduction was the average consumption in the corresponding months in the five-year period 2017–2022.

All three countries introduced measures to reduce demand; however, these were introduced before the CR. Most of these measures can be characterized as command-and-control measures and information campaigns. For instance, public institutions in Sweden and Denmark are required to implement energy-saving measures, such as reducing indoor temperatures in buildings and switching off lights, ventilation, screens, electronic devices, etc., where possible. Moreover, there are information campaigns, such as “Every kilowatt-hour counts” in Sweden and “Down a Degree” in Finland, apprising public institutions, businesses and households about energy saving possibilities.

In addition to information campaigns and command-and-control measures, demand reduction schemes were introduced by the TSOs in Sweden and Finland.

- In Sweden, a flexibility procurement scheme was introduced in November 2022. Under this scheme, large consumers were compensated for shifting their power demand from peak load hours to other periods. In total, 75 MW were procured under the scheme. In spite of its name, the scheme was not particularly flexible: eligible consumers were compensated for reducing consumption during certain hours, regardless of the situation in the power market. The scheme was closed in February 2023, as the total reduction of electricity demand in the rest of the market was sufficient and made the procurement scheme unnecessary.

- In Finland, Fingrid introduced a voluntary power system support procedure. Fingrid entered into agreements with about 50 companies and public entities that agreed to reduce their demand in a power shortage. If the risk of a blackout or brownout occurs, Fingrid will contact them by text message the day before to warn them about the risk. The companies and public entities will only be asked to activate the emergency measures when there is a real need. They are not compensated for this other than through price effects in the market. Fingrid has pointed out that an important part of the scheme is the identification of potential measures and the education of the employees of the participating companies.

Data have revealed that electricity consumption was reduced in the winter months of 2022–2023 in all three countries. Peak-hour consumption was reduced well beyond the target of 5%: 8.3% in Finland, 9.1% in Sweden and 10.2% in Denmark. Figure S.1 shows the reduction for each month. The reduction of total electricity consumption has also been considerable in all three countries (see Figure S.2), especially in January and February.

Figure S.1. Average consumption reduction during peak hours, December 2022–February 2023

Source: Vista Analyse, based on reports from the TSOs

Source: Vista Analyse, based on reports from the TSOs

Figure S.2. Total consumption reduction, November 2022–March 2023

Source: Vista Analyse, based on reports from the TSOs

Note: Figures have been temperature-adjusted for Sweden and Finland (December–February).

Source: Vista Analyse, based on reports from the TSOs

Note: Figures have been temperature-adjusted for Sweden and Finland (December–February).

A thorough analysis of the different measures’ impacts on consumption is outside the scope of this project, as data became available only towards the end of the assignment. Therefore, we cannot distinguish between the effects of individual measures and the effects of prices. On average, electricity prices were slightly below 250 EUR/MWh in Denmark, Finland and Southern Sweden in December 2022 and around 100 EUR/MWh in January 2023. Moreover, the winter of 2022–2023 was relatively mild, contributing to lower demand in Finland and Sweden. However, there are two interesting points to note:

- A large reduction in demand occurred in January, when prices were significantly lower than in December. This may imply a time lag in demand reduction, which may have been due to either more information becoming available and increased awareness of the prices or to more possibilities for reducing demand over time. In addition, total electricity consumption was reduced the most in Denmark, where electricity demand is independent of temperature.

- The reduction of demand in peak hours in Sweden was considerably larger than the 75 MW (corresponding to less than 0.4% of peak demand) procured by the flexibility procurement scheme. Hence, the reduction in electricity consumption in the rest of the economy was significant.

Revenue cap and tax on profits

The second emergency measure in the CR involved a cap on revenues from electricity production: 90% of revenues exceeding 180 EUR/MWh were taxed. This applied to most electricity producers with marginal costs lower than the market price (the so-called inframarginal producers). The revenue cap applied until 30 June 2023.

The implementation of the revenue cap was almost identical in Sweden and Denmark and matched the requirements of the CR. The main difference was that in Sweden, tax was calculated based on the hourly day-ahead price, while in Denmark, the price obtained in the different markets (day-ahead, intraday and balancing markets) was used, and the tax was calculated as a monthly average. Hedging agreements were taken into account in both countries; thus, the actual price that the producer received was the tax base. In addition, in Sweden, the tax applied to revenues obtained between 1 March 2023 and 30 June 2023.

Both countries used the exemption possibilities available in the CR. There was a special cap corresponding to 1.3 times production costs for some high-cost producers in Sweden. In Denmark, the actual fuel prices of high-cost technologies, such as biomass- and oil-fired power plants, were taken into account. Similar to gas prices, the fuel prices of these plants recently increased.

In Finland, a profit tax was implemented instead of a revenue cap. This is a temporary tax of 30% on profits (from electricity sales) exceeding an annualized return of 10% on equity. This tax applies only to 2023; it is to be phased out after 2024.

Impacts of the revenue cap on the Nordic wholesale power market

We assessed the short- and long-term impacts of the revenue cap on the wholesale electricity markets. The main question was whether the revenue cap on inframarginal technologies would affect the incentives of power market participants. The short-term impacts were related to incentives to produce, while the long-term impacts were related to incentives to invest in new capacity.

Short-term impacts

Our main findings related to the revenue cap in Sweden and Denmark include the following:

- In principle, inframarginal producers’ incentives to produce are not affected by a revenue cap: producers will produce as long as their marginal revenues are larger than their marginal costs. Taxing only 90% of revenues exceeding 180 EUR/MWh contributes to maintaining incentives to produce.

- Special provisions for high-cost producers (biomass and oil-fired power plants) ensure that their incentives are preserved, thus ensuring security of supply.

- The way the tax was implemented in Sweden, with a day-ahead price as a reference price and hourly prices for settlements, does not influence producers’ short-term incentives. The impacts of using the monthly average price, as was done in Denmark, are not straightforward, but the incentives were preserved in Denmark as well.

- The actual prices obtained by the producer formed the tax base. Hence, if a producer had hedging agreements or power purchasing agreements (PPAs) and did not earn a market price exceeding 180 EUR/MWh, the tax did not apply. The share of hedging agreements in the Nordic market is relatively high. In particular, wind and solar producers are hedged to a large degree. Therefore, a large share of the production was not influenced by the tax, even when spot prices were high.

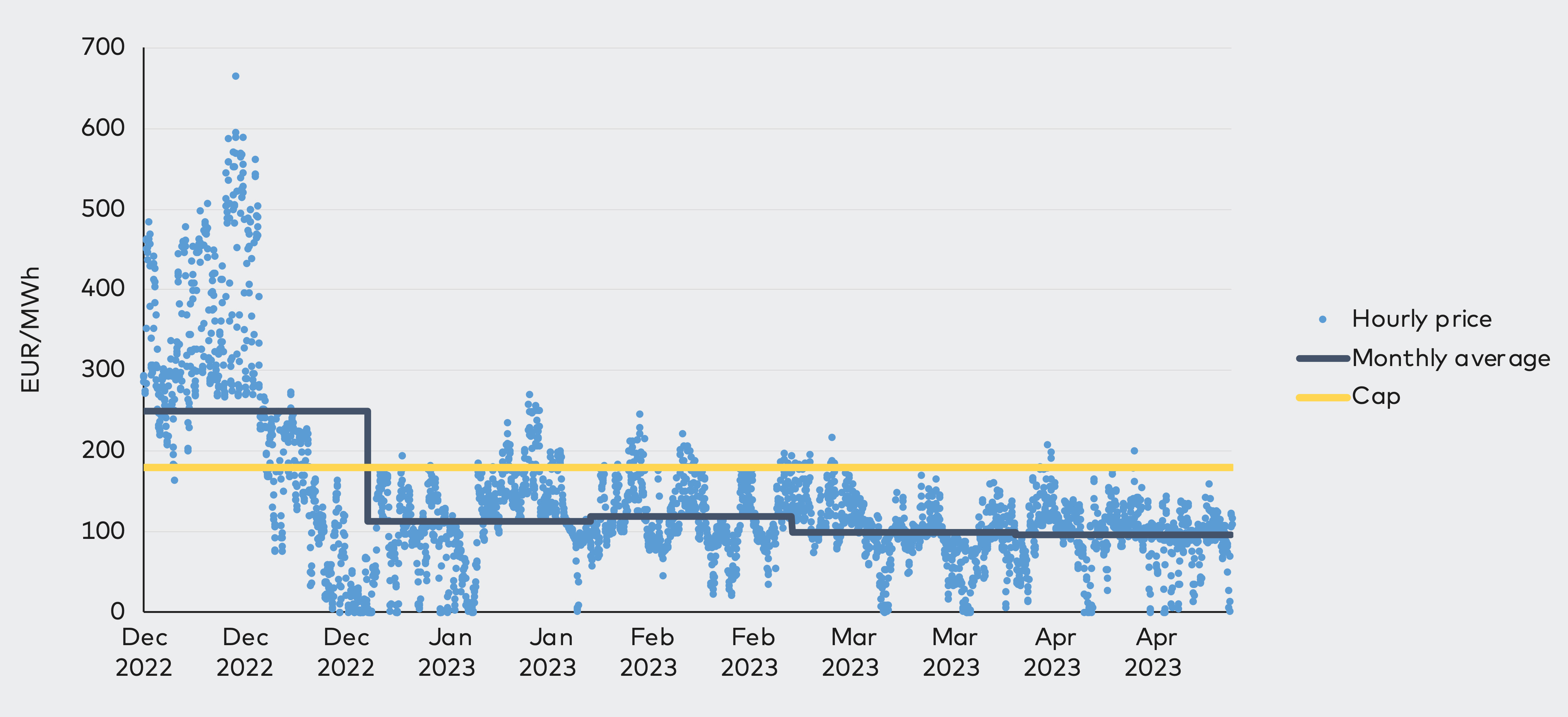

- Using the monthly average price as the tax base is likely to reduce the administrative costs of the tax. However, it also reduced tax revenue, as illustrated in Figure S.3. Recall that the tax in Sweden applied only to revenues obtained between March–June 2023.

Figure S.3. Hourly and monthly average prices in Denmark (DK1, day-ahead)

Source: Vista Analyse, based on data from ENTSO-E

Source: Vista Analyse, based on data from ENTSO-E

Our main findings related to the profit tax in Finland include the following:

- A profit tax does not distort short-term production incentives. Profit-maximizing firms maintain incentives to maximize profits, even if a share of the profits is taxed. Thus, rational agents in the electricity sector behave as before and offer the same supply in the same markets.

- A profit tax is easier to implement and has lower administrative costs than a revenue cap.

- The present profit tax implies a higher tax level in Finland than the revenue tax in Denmark and Sweden, as the profit tax was calculated to be equivalent to a revenue tax for electricity prices of 280 EUR/MWh and applies to a longer period. While this does not influence short-term incentives, it influences competitiveness and may influence long-term investment decisions.

Long-term impacts

The potential long-term impacts relate to incentives to invest. Investment decisions depend on expectations about future prices and cash flows. Therefore, the main question is how these crisis measures influence expectations about the future - whether investors believe that policymakers will implement a revenue cap or profit tax (or other extraordinary measures) whenever prices are particularly high. If they believe that a similar tax will be introduced in the future, the expected after-tax profitability of new investment projects will be reduced, and investments may be reduced as well. To maintain incentives to invest, it is important to emphasize that the measures were introduced as a response to an extraordinary crisis and not as regular taxes.

Electricity prices are much higher now than they were prior to 2021. Investments have been planned and carried out at much lower prices than those of today. However, uncertainty about market conditions in general – prices and taxes – may cause some investors to postpone making decisions.

It is worth noting that differences in the implementation of the measures may lead to changes in competitiveness between the countries. This could have long-term impacts, such as investments being “moved” from one country to another. Again, the negative effects on investment can be mitigated by communicating that these crisis measures are unlikely to be used again.

Hence, if investors believe that the current emergency measures are exceptional and time-limited crisis measures indeed, long-term incentives to invest should not be affected. Therefore, it is crucial that the authorities emphasize the temporary, one-time nature of these extraordinary measures.

Solidarity contribution from the fossil fuel sector

The third measure is the solidarity contribution from the fossil fuel sector. This involves a mandatory contribution of at least 33% of the taxable profits in fiscal years 2022 and/or 2023 that are higher than 20% of average profits in the four preceding fiscal years. This applies to companies with activities in the crude oil, natural gas, coal and refinery sectors. This measure appears to be less relevant for the three countries of this study, as no such companies were identified in Finland, and only a few relevant companies were identified in Sweden and Denmark.

The fossil fuel solidarity contribution is, in essence, an extraordinary tax on the profits of fossil fuel companies. A profit tax does not influence short-term incentives to produce, but it may influence long-term incentives to invest if it influences expectations about future net tax revenues. Representatives of the fossil fuel sector have argued that the solidarity contribution may reduce investments in green technologies. However, the profitability of green investments will not change because of the tax on fossil fuel companies. Other companies will invest in green technologies as long as these investments are profitable relative to other investments in the economy. Moreover, as stated, if companies are convinced that the tax is a temporary and extraordinary measure, incentives to invest will not be affected.

Conclusions

The Nordic electricity market has responded relatively well to the current crisis. The increased prices, together with information and awareness campaigns and other measures, resulted in lower demand in the 2022–2023 winter. The reduction in demand during peak hours in Sweden was considerably larger than the 75 MW procured by the flexibility scheme. Hence, the reduction in electricity consumption in the rest of the economy was significant. Based on the current data, it is difficult to distinguish between the effects of the special measures and the effects of prices.

The revenue cap on inframarginal technologies, as implemented in Denmark and Sweden, does not distort short-term incentives to produce to a significant degree. However, administrative costs may be high. Considering that power prices have been much lower in 2023 than they were in the second half of 2022, the actual tax revenue from these measures is relatively low.

A profit tax, as implemented in Finland, is theoretically better than a revenue cap. In addition, the administrative costs of a profit tax are likely to be lower.

Different tax schemes may influence the competitiveness of producers in different countries. In the long term, this could lead to investments being “moved” from one country to another.

The main potential impacts of the emergency measures relate to incentives to invest in new production capacity. If investors believe that the current emergency measures are indeed exceptional, targeted and time-limited, as stated in the Council Regulation, the long-term incentives to invest should not be affected. If, on the other hand, they expect new crisis measures to be implemented whenever prices are exceptionally high, they may hesitate to invest. Hence, it is crucial that the authorities emphasize the temporary, one-time nature of these extraordinary measures – as also stated in the Council Regulation.