Photos: iStock and Unsplash

Concepts: The maritime sector or the blue bioeconomy?

In recent decades, the concept of the blue bioeconomy has emerged in numerous publications, replacing the conventional concept of the maritime sector or economy. In this report we use both concepts in flux. However, it is important to stress that, conceptually, the blue bioeconomy has a broader reference framework and also relates to newly emerging and often innovative practices or activities associated with the sea. A report by the Nordic Council of Ministers on “25 Cases for Sustainable Change” defined bioeconomy as follows back in 2017: “Responsible use of renewable biological resources from the land and water for the mutual benefit of business, society and nature”. It is a value-laden approach in the sense that the transition to bioeconomy is intended to create a more resource-efficient economy based on increased value added for bio-mass materials and a reduction in energy consumption. Renewable biological resources may be converted into food, feed, biofuels, bioplastics and bio-pharmaceuticals. (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2017).

That view of a responsible blue bioeconomy (which is more geared towards a circular economy than conventional approaches to the industry) corresponds to Nordic visions and the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Job generation in blue bio economy corresponds well with serveral aims in the Nordic vision

Aim 1: Promote green transition and carbon neutrality and a sustainable circular economy.

Aim 2: Securing biological diversity and sustainable harnessing of nature and oceans of the Nordic Region.

Aim 6: Together we will promote green growth in the Nordic Region based on konwledgement, innovation, mobilities and digital integration.

Aim 7: Develop competences and well functioning labour markets matching the reguriements of green transition and digital development, supporting free movement in the Nordic Region.

Figure 1. Aims of the Nordic vision connected to the blue bioeconomy

(Karlsdóttir, 2021)

(Karlsdóttir, 2021)

The modern-day blue bioeconomy includes a range of economic activities based on intelligent and sustainable use of bioresources, focusing on improved utilisation, use of novel bioresources and creation of higher-value products. Products include food, animal feed, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and various chemical compounds. A blue bioeconomy based on sustainable development means that the needs of the present are met without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Arctic Council 2021).

However, a review of milestone literature on the blue bioeconomy (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2017; European Commission, 2019, Arctic Council, 2021, Nordic Council of Ministers, 2021) reveals that the approach taken to maritime activities in society is generally gender-blind.

Furthermore, this newer conceptual framework and approach has not gone uncriticised. Albrechts & Lukkarinen (2020), for example, note that the blue bioeconomy is gaining momentum in EU policy and the strategies of various national governments and receives substantial funding; yet while the blue bioeconomy promises regional economic development and is portrayed as holistic, it involves little integration of freshwater perspectives or alternative development paths (Albrecht & Lukkarinen, 2020). Moreover, advocates of this conceptual framework and approach state they address climate change. However, it makes it necessary to question in some cases. Primarily why regional bioeconomies seem to have an easy access to public finance priorities, since it is not being proofed to be more sustainable in all cases (Albrecht, Grundel, & Morales, 2021). Thus, as claimed by Albrecht et al., there may be challenging mismatches between policy narratives, local development processes and potential.

However, our primary focus is on the gender perspective. We wish to stress that the notion of gender, women or equality, with very few exceptions (Svels et al., 2022; EMOUFA, 2023), is almost completely absent from literature on the blue bioeconomy. This failure to prioritise gender equality in the fishing industry is a challenge with respect to safeguarding local communities along the coast (Kilden, 2022).

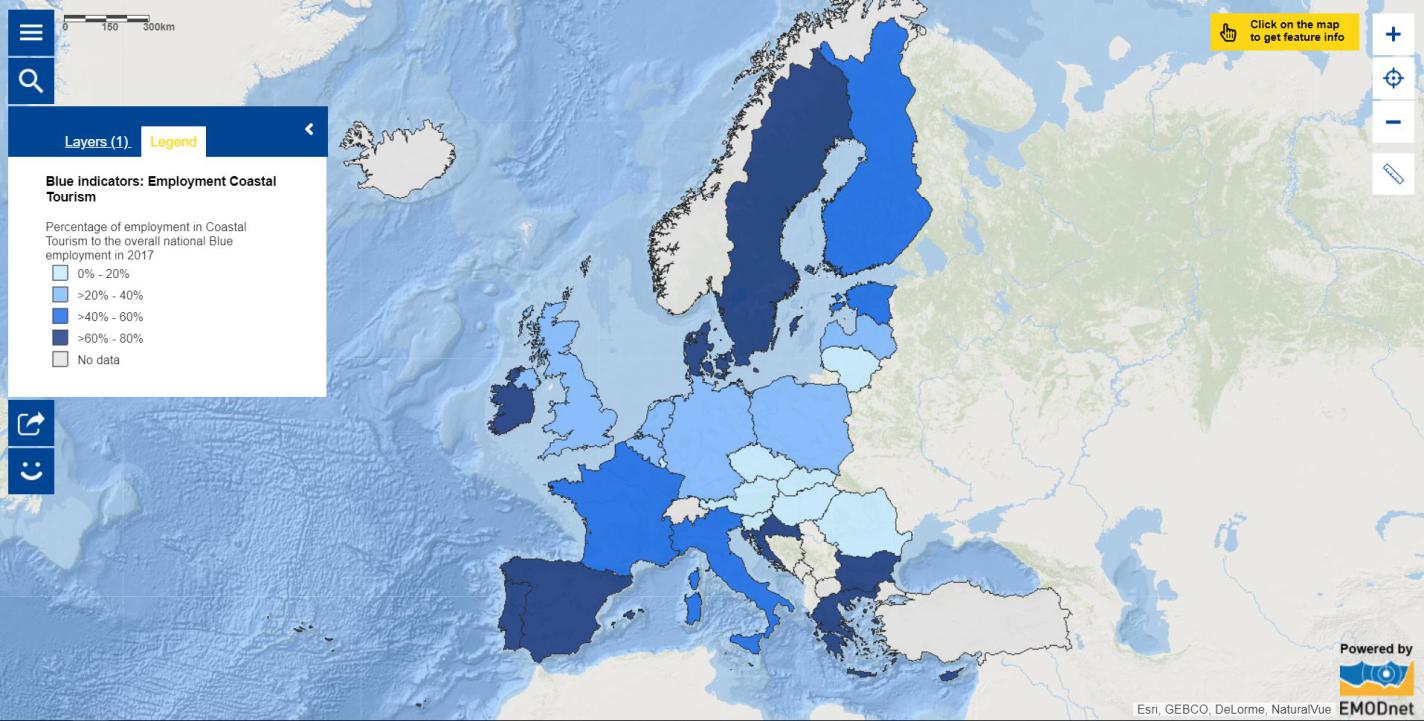

While we would have liked to study the place of women in the blue bioeconomy, due to the timeframe and scope of the project, we have had to focus on women in the maritime sector. One way to identify women’s role and influence is to look at value chains. It is important to broaden the conventional view of fisheries and aquaculture since the presence of women is substantial in all the various layers and dimensions of the blue bioeconomy, up through the relevant value chains. For example, according to a recent study produced by the EU, coastal tourism continues to generate the largest share of employment and gross value added (GVA) in the EU blue economy (European Commission, 2023; Iceland, Norway Lichtenstein grants, 2022). If the maritime sector is extended to the blue economy sector, Finland, Åland, Sweden and Denmark would increase in importance in that sector compared to Norway, Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands.

Figure 2. Employment in coastal tourism.

Source: European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet)

Source: European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet)

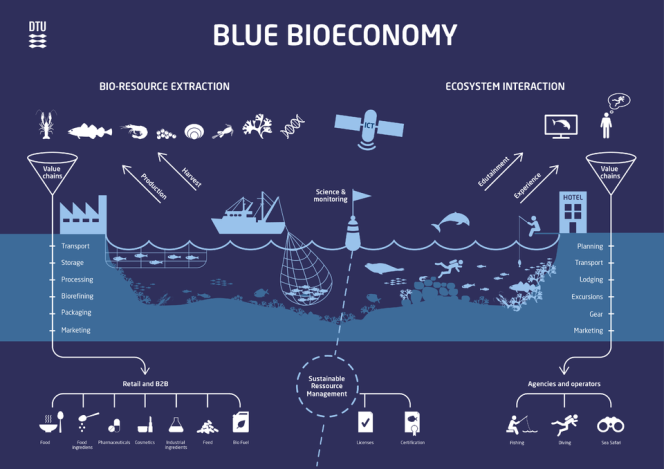

Figure 3. An overview of the blue bioeconomy.

Source: DTU-Aqua 2019

Source: DTU-Aqua 2019

The blue bioeconomy works with living resources, ecosystem goods and services provided by the sea for human use, value chains and interaction chains from sea to land (and vice versa).

The graphic above distinguishes between three main types of value chains: 1. The extraction of life-based resources (bio-resource extraction) and 2. Human uses that are non-extractive (ecosystem interaction). The former includes the hunting and harvesting of living resources (fishing and bio-prospecting) or their production (various forms of aquaculture). This describes the value chain of extractive uses from harvest/production to transport (some parallel, some serial). While it produces value, it also impacts on the ecosystems and species in question and their resilience and capacity to reproduce. The non-extractive, latter types of uses include experiential and educational aspects (edutainment, experience). These may have impacts and need infrastructure, which in turn provide further opportunities for value creation (but also have environmental and societal impacts). 3. Science and monitoring support evaluation and knowledge-based planning and management e.g. through the provision of licences and the certification of marine uses.

There are also other value chains, e.g. related to energy and non-living resources. Marine space may be regarded as an important prerequisite (raising the question of whether it can be considered an ecosystem service).

The representation of women varies highly from one value chain to another, but also along value chains. If, for example, women’s engagement in coastal tourism activities is included, we have to broaden the horizon beyond just the maritime sector. The argument holds weight that a broader view of the maritime sector (or seafood sector) should be taken to capture the important efforts of women in coastal regions of the Nordic countries and provide a genuine overview of the numerous women involved across the value chain. The focus needs to be widened to encompass the entire broader value chain now often coined the blue bioeconomy.