Chapter 1: Introduction

Frederik Forrai Ørskov

The concept of Nordic added value has increasingly come to serve as a guiding principle of inter-ministerial Nordic co-operation and its related institutions since the mid-2000s. Whether as a description of the rationale behind Nordic co-operation as a whole, a justification for the significant amounts of taxpayer money invested in institutions operating at a Nordic level, or an assertion of the continued significance of Nordic co-operation in the face of increasing European integration and global challenges, Nordic added value has become the English-language concept of choice.

In addition to its frequent appearance as a celebratory shorthand in official speeches, there have been significant attempts to operationalise the principle of Nordic added value and have it serve as a focal point in efforts to reform Nordic co-operation, prioritise the allocation of funding, and align efforts in the various branches and institutions of Nordic inter-ministerial co-operation and associated political goals. As a result, the institutions, projects, and actors involved in Nordic co-operation have increasingly been tasked with accounting for the Nordic added value in their work.

In short, Nordic added value is generally perceived as a description of the effect of joint Nordic efforts that could not be obtained if those same efforts were carried out at a different level than the Nordic. With reference to an oft-invoked slogan, Nordic added value is meant to identify areas where the Nordics are stronger (when working) together and describes the outcome of joint efforts in those areas.

However, despite its frequent usage, appearing in “almost all Nordic cooperation programmes,”

Que Anh Dang, “‘Nordic Added Value’: A Floating Signifier and a Mechanism for Nordic Higher Education Regionalism,” European Journal of Higher Education 13, no. 2 (2023): 147.

Tuire Liimatainen, “Nordic Added Value in Nordic Research Co-Operation: Concept and Practice” (Oslo: NordForsk, 2023), 57.

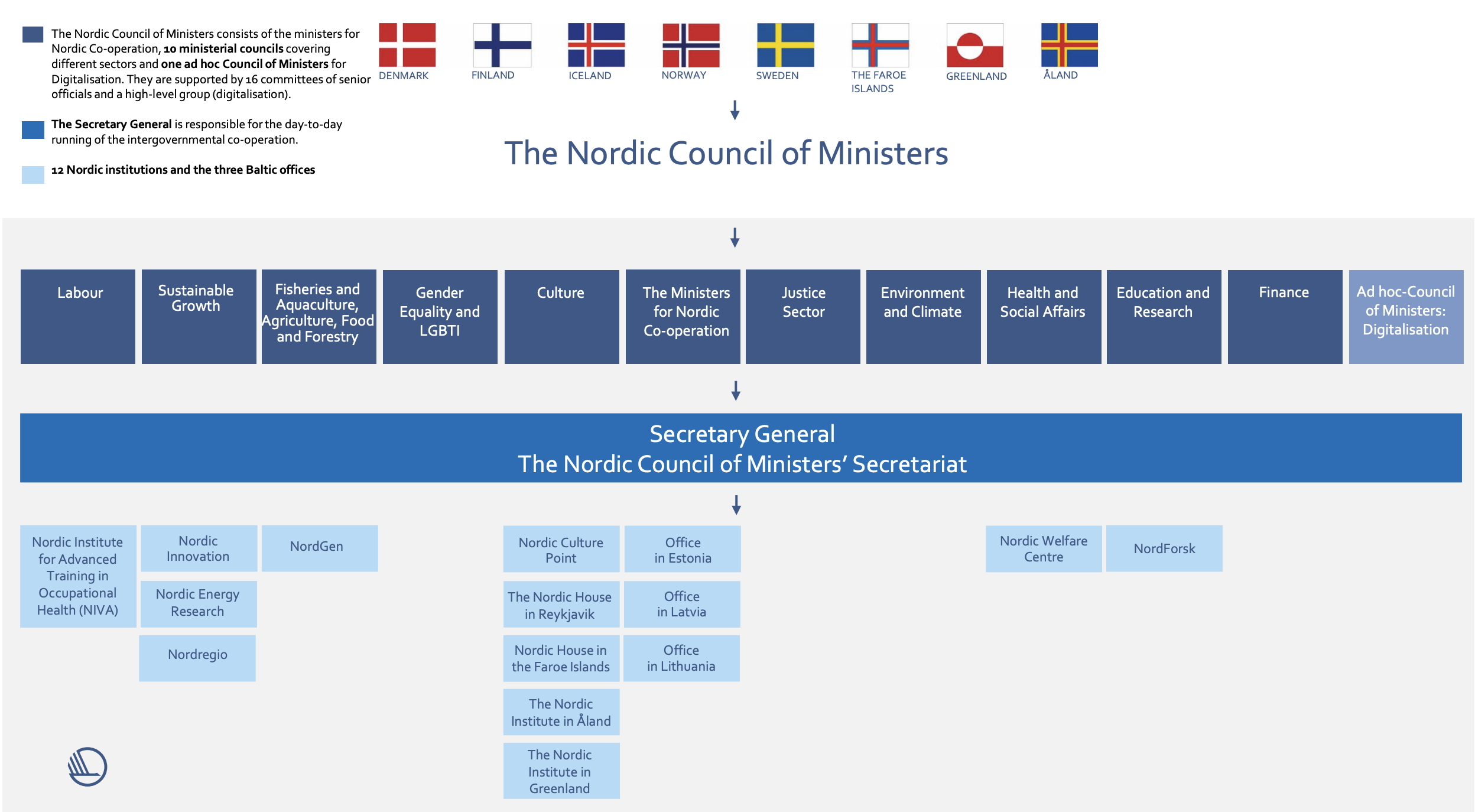

Figure 1 Organisational diagram for the Nordic Council of Ministers. Reproduced from: https://www.norden.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/Organisationsdiagram.pdf

In assessing the prominence of Nordic added value in Nordic co-operation practices today, the fluidity and multi-dimensionality of the concept is both a strength and a weakness. It is a strength because it has contributed to the concept’s broad circulation and continuous re-application within the different sectors of Nordic co-operation, where different actors and audiences can simultaneously find things to treasure in (their interpretations of) the concept.

For a similar point on the notion of the Nordic model, see Haldor Byrkjeflot, Mads Mordhorst, and Klaus Petersen, “The Making and Circulation of Nordic Models: An Introduction,” in The Making and Circulation of Nordic Models, Ideas and Images, eds. Haldor Byrkjeflot et al. (London; New York: Routledge, 2021), 3.

On some of the difficulties involved in the Nordic Council of Ministers’ inter-sectoral work, see Ulf Andreasson and Truls Stende, “Tvärsektoriellt arbete i Nordiska ministerrådet,” Internal Report (Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers, n.d.).

Given the close association frequently drawn between Nordic added value and the very legitimacy of Nordic co-operation, a clearer understanding of the concept will help to clarify the sense of purpose within the institutions of Nordic co-operation – but if the baby is not to be lost with the bathwater, this understanding must reflect the holistic and changeable nature of Nordic co-operation.

Starting points

The 2023 NordForsk-report Nordic added value in Nordic research co-operation: Concept and practice, written by Tuire Liimatainen, recommended that efforts be made to promote “a holistic understanding of the concept and its various interpretations,” not just in Nordic research co-operation but also as part of “a broader discussion of the objectives of Nordic co-operation” that should preferably involve “a comparative discussion of the operationalisation of Nordic added value in different joint institutions.”

Liimatainen, “Nordic Added Value in Nordic Research Co-Operation,” 58.

Currently, the strategic objectives of Nordic co-operation are largely outlined in the Vision 2030 agenda for Nordic co-operation, adopted by the Nordic prime ministers in 2019. The high priority accorded to the implementation of Vision 2030 across all sectors of Nordic co-operation prompts an exploration of the meanings and uses of Nordic added value in relation to the ambitions outlined in the vision, and of the appropriate role of the concept in the pursuit of these ambitions. According to the Vision 2030, the institutions of Nordic co-operation must work towards making the Nordic region the most sustainable and integrated region in the world by 2030 by pursuing three strategic priorities:

- A green Nordic region, prioritising efforts to promote the green transition of the Nordic societies and a shift towards carbon neutrality and a sustainable economy.

- A competitive Nordic region, prioritising efforts to promote green growth in the Nordic region through knowledge, innovation, mobility, and digital integration.

- A socially sustainable Nordic region, prioritising efforts to promote inclusivity, equality, and interconnectedness in the Nordic region through shared values, cultural exchange, and welfare.Nordic Council of Ministers, “Our Vision 2030 | Nordic Cooperation,” accessed October 18, 2023, https://www.norden.org/en/declaration/our-vision-2030.

These priorities presuppose significant efforts in all sectors of Nordic societies. Is the principle of Nordic added value geared to stand at the centre of such a wide-ranging, multi-sectorial process, encompassing all branches of Nordic co-operation and, by extension, Nordic societies? And does it exacerbate or help resolve the tensions that can arise from efforts to address the substantially different ambitions and priorities outlined in Vision 2030? That is, most obviously, potential tensions between the aim of stronger regional integration that has traditionally been at the heart of Nordic co-operation on the one hand, and the much newer goal of leveraging the framework of Nordic co-operation as a driver of sustainability on the other.

Notably, Nordic added value is not explicitly mentioned in the Vision 2030 document. If Vision 2030 set outs the overall direction for Nordic co-operation, there is a need to consider if and in what form Nordic added value – as a central operational concept as well as an institutionalised way of articulating the legitimacy of Nordic co-operation – relates to the priorities outlined in Vision 2030.

The challenges of Nordic added value

Liimatainen’s report explored how Nordic added value has been conceptualised and practiced in the Nordic research co-operation facilitated by NordForsk. It found that, at policy level, the contemporary meaning of Nordic added value can be defined as:

The positive effects of joint Nordic efforts that strengthen the Nordic region as a cultural and historical community, and as a locally and globally competitive and sustainable welfare society.

However, the report also found that the operationalisation of the concept Nordic added value presented several challenges relating to its pragmatic use in Nordic co-operation.

This section is largely based on Liimatainen, 23–25; see also Emilia Berg, “Sharing is Caring: The Official and Practical Understanding of the Concept Nordic Added Value in the Field of Social and Health Policy,” (MA Thesis, University of Helsinki, 2023).

- Nordic added value is a value-based concept, articulating cultural, social, and economic value-systems. This presents challenges when the concept is operationalised because:

- Value-based concepts tend to be prone to ambiguity, vagueness, and abstraction, not least because the notion of “value(s)” warrants both concrete/material and abstract/immaterial interpretations.See also Daniel Tarschys, The Enigma of European Added Value: Setting Priorities for the European Union, vol. 4 (Sieps, 2005); Claes Lennartsson and Jan Nolin, “Nordiska kulturfonden: en utvärdering och omvärldsanalys 2008” (Nordisk ministerråd, 2008).

- Value-based concepts are difficult to differentiate from supposedly contrasting value-based concepts (how, for example, do Nordic values exactly differ from supposedly European or Western values?).Klaus Petersen, “Nordiske Værdier: Et Kritisk Reflekterende Essay,” in Meningen Med Föreningen: Föreningarna Norden 100 År, ed. Henrik Wilén (Föreningarna Norden, 2019), 79.

- Value-based concepts contain an inherent tension in the process of translating between policy and practice, meaning that different interpretative possibilities are available when the overall aim of creating Nordic added value is transformed into goals for target-oriented action among different organisations and stakeholders.Kim Forss, Nordens Hus Och Institut: En Utvärdering Av Mål, Verksamhet Och Resultat (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2014), 56; Lennartsson and Nolin, “Nordiska kulturfonden,” 50; Anna Kharkina, “From Kinship to Global Brand: The Discourse on Culture in Nordic Cooperation after World War II” (PhD Dissertation, Stockholm, Stockholm University, 2013), 96–98; Dang, “‘Nordic Added Value’: A Floating Signifier and a Mechanism for Nordic Higher Education Regionalism,” 15.

- Uses and interpretations of Nordic added value (as well as other concepts articulating the legitimacy and outcomes of Nordic co-operation) are highly context-dependent, meaning that they tend to depend on and change according to:

- disciplinary and institutional differences across the inter-sectoral framework of Nordic co-operation and the many policy areas it spans;

- historical, cultural, political, and geo-political circumstances;

- the levels (regional, European, or global) at which Nordic efforts address issues or are perceived to generate added value; and

- the individuals interpreting Nordic added value and their personal and professional backgrounds.

An additional challenge can be found in the fact that Nordic added value is one – by now arguably the most prevalent – concept among many that articulates the foundations and outcome of Nordic co-operation, potentially making it difficult for stakeholders to communicate with reference to the different concepts. The saturation of concepts is even greater when taking into account the many Nordic institutions that do not primarily use English as their primary working language.

Lennartsson and Nolin, “Nordiska kulturfonden,” 12.

English language concepts: | Scandinavian-language concepts (here Swedish) |

|---|---|

Nordic benefit/Nordic advantage/Nordic usefulness Nordic added value/Nordic synergy Nordic dimension Nordic affinity Nordic level Nordic competence Nordic strength (Nordic values) | nordisk nytta nordiskt mervärde/nordisk synergi nordisk dimension nordisk samhörighet nordisk nivå nordisk kompetens nordisk styrka (nordiska värderingar) |

Table 1 Examples of concepts articulating legitimacy and outcomes of joint Nordic efforts

To this end, relatively divergent understandings of Nordic added value exist across and within the individual institutions for Nordic co-operation, as do relatively broad or relatively simplified, and therefore more immediately operational, interpretations.

Liimatainen, “Nordic Added Value in Nordic Research Co-Operation,” 15–16; see also Berg, “Sharing is Caring.”

Forss, Nordens Hus Och Institut: En Utvärdering Av Mål, Verksamhet Och Resultat, 12; Lennartsson and Nolin, “Nordiska kulturfonden,” 270.

Translating Nordic added value in a multilingual framework of co-operation

As noted above, the conceptual field of Nordic co-operation increases in complexity when taking translation into account in the multilingual institutional framework of co-operation. While Nordic co-operation traditionally drew upon the high level of mutual comprehension among speakers of the Scandinavian languages, this has been changing in recent decades. English has grown in prominence both in official communication and within the institutions of Nordic co-operation. While a controversial issue and regarded as a threat to the core identity of Nordic co-operation by some, others highlight that this development levels the playing field, potentially leading to increased inclusivity within Nordic co-operation where native speakers of Finnish, Icelandic, Faroese, Greenlandic, and the Sami languages, as well as newcomers to the Nordic region, are not at risk of being regarded as “second-tier Nordic citizens” through linguistic exclusion.

Johan Strang, “The Role of English in the Nordic Language System,” in English in the Nordic Countries: Connections, Tensions, and Everyday Realities, eds. Elizabeth Peterson and Kristy Beers Fägersten (New York: Routledge, 2023), 23–46.

The rising prominence of English adds to the conceptual confusion primarily because there is no standardisation of how the concepts articulating legitimacy and outcomes of joint Nordic efforts are translated between English and the other working languages of Nordic co-operation. In practice, Nordic added value is used as the English-language equivalent for both nordiskt mervärde and nordisk nytta, disguising the subtle differences that exist between them.

Liimatainen, “Nordic Added Value in Nordic Research Co-Operation,” 15; Erik Arnold, “Rethinking Nordic Added Value in Research,” NordForsk Policy, 2011, 20–22; Dang, “‘Nordic Added Value’: A Floating Signifier and a Mechanism for Nordic Higher Education Regionalism,” 6–7.

This report deals with translation issues in the following way:

- When discussing historical debates or other issues where the usage of specific Scandinavian-language terms is significant, these are retained in the text.

- Where official translations into English exist, these are used in the report as well, but with the original Scandinavian-language term added in brackets when relevant and available.

- In other cases, the currently most common practice of translating both nordiskt mervärde and nordisk nytta (as well as their other Scandinavian and Finnish-language equivalents) as “Nordic added value” is used.

Aims and objectives

This report examines the interpretations and uses of Nordic added value across the institutional framework of official inter-ministerial Nordic co-operation by posing the following question:

- How is (and has) Nordic added value (been) conceptualised within the Nordic Council of Ministers and its different subsidiary institutions?

The report provides a qualitative analysis of Nordic co-operation practices and of different justifications for Nordic co-operation in order to contribute to discussions of how (and whether) Nordic added value can serve as a tool in the formulation of goals and activities that will allow the institutions of Nordic co-operation to:

- meet the ambitions for Nordic co-operation set out in Vision 2030;

- steer economic decisions in alignment with those ambitions;

- consolidate the political legitimacy of Nordic co-operation;

- safeguard and further develop the cultural identity, regional inter-connectedness, and shared values that make up the foundations of successful Nordic co-operation; and

- assert the relevance of Nordic co-operation in relation to politics, civil society, and the wider public in the individual Nordic countries, as well as in relation to the EU and other international and inter-regional forms of co-operation.

To this end, the report first offers a historical outline of Nordic added value’s rise to prominence among the concepts used to legitimise Nordic co-operation, before going on to look in more detail at the historical and contemporary uses and meanings of Nordic added value in the specific sectors and institutions of official inter-ministerial Nordic co-operation.

The report does not aim to look at every institution at every level of official Nordic co-operation. Most notably, the report is limited to inter-ministerial co-operation. To this end, the report does not outline how Nordic added value is and has been used and conceptualised in the inter-parliamentarian Nordic co-operation that takes place in the Nordic Council and related venues, or in the joint Nordic efforts that take place in civic society organisations outside the realm of official Nordic co-operation.

The institutions surveyed in the report, on the other hand, have been chosen so as to offer comparative perspectives on the histories, uses, and understandings of Nordic added value across the widely differing branches of Nordic inter-ministerial co-operation (see Figure 1).

It must be emphasised that the goal is not to evaluate how “well” or “poorly” the individual institutions operationalise or have operationalised Nordic added value, or what that would even mean. Being a qualitative study, the report instead aims to unpack the various dimensions that the concept has obtained or been accorded across the different sectors and institutions of inter-ministerial Nordic co-operation. The aim is to help clarify the different interpretations of the concept in an effort to guide the various sectors of Nordic co-operation, both today and tomorrow, towards common goals, and to do so in a way that does not lose sight of the fact that these sectors differ in terms of the potential value they can add to Nordic co-operation and that they operate according to different logics.

Materials and methods

The report builds on a review of relevant aspects of the research literature available on Nordic co-operation and Nordic added value, as well as on a qualitative analysis of institutional documents and interviews with central stakeholders who hold or have held relevant positions in the institutions of Nordic co-operation. The report’s analysis is inspired by methods from the field of research known as conceptual history – although methodological reflections are kept to a minimum.

The institutional documents analysed for the report have been selected by the research group based on an informed understanding of their relevance in outlining the visions, practices, and results of the different branches of official inter-ministerial Nordic co-operation. Current or former officials from the following institutions have been interviewed: the Secretariat to the Nordic Council of Ministers, the Nordic Council, the Nordic House in Reykjavik, Nordic Culture Point, the Nordic offices in Riga, Vilnius and Saint Petersburg, the Nordic House on the Faroe Islands, the Nordic Institute in Greenland, the Nordic Institute on Åland, the Nordic Council’s office in Brussels, the Nordic Welfare Centre, Nordregio, NordForsk, Nordic Energy Research, and Nordic Innovation. All interviews apart from one (with a former Secretary General of the Nordic Council of Ministers) have been anonymised to ensure that the answers were as candid as possible.

The report has been co-authored by a team of researchers. Emilia Berg has written on the Nordic Welfare Centre, Essi Turva on the Nordic House in Reykjavik and Nordic Culture Point in Helsinki, and Hasan Akintug on the Nordic Council of Ministers’ offices in the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland. Tuire Liimatainen has written on NordForsk, Nordic Energy Research, and Nordic Innovation. Frederik Forrai Ørskov and Tuire Liimatainen have co-authored the historical outline chapter and the comparative analysis and findings sub-chapter, while Frederik Forrai Ørskov has been the main editor of the report and the author of its remaining parts.