4. Findings of work package 2: Use of health services in another Nordic or Baltic country

Work package 2 (WP2), in the project Achieving the World’s Smoothest Cross-Border Mobility and Daily Life through Digitalisation funded by the Nordic Council of Ministers, focused on questions related to the use of health services in another Nordic or Baltic country. The project started by conducting a baseline study.

This work package presents an overview of the current capabilities of the Nordic and Baltic countries when it comes to the exchange of healthcare data, different structures, ongoing development actions in the field, and plans concerning ePrescriptions and patient summaries. Moreover, there are many technical and semantic interoperability challenges related to current exchange practices of ePrescriptions and patient summaries. In general, the countries are using different systems and databases for different purposes, such as ePrescriptions, vaccinations, health records and social welfare. Moreover, the content of the patient summary data sets significantly varies between the countries, but standardised fields or a minimum data set are usually found. In some countries, the compilation of a patient summary is manual, whereas other countries compile it more automatically from different documents or source systems.

It is also important to stress that not only are citizens targets of data exchange, but they also play a central role in cross-border data exchange by allowing, or denying, their data to be shared with different stakeholders. MyData principle

Finally, the professionals at the actual implementation level testing and developing the services is essential. Additionally, the amount and quality of data depends heavily on the healthcare providers and how they update the fields. This affects the quality of the data in the systems.

4.1 The importance of cross-border exchange of health data

Continuity of care

People may need to request medical care when travelling, working, studying, or living abroad. In addition, patients in the EU have the right to utilise the closest healthcare provider regardless of the place of residence. A patient’s health information recorded in the country of affiliation, such as the medical background and related history, should be available upon request to all healthcare professionals in Europe, when a need for that information arises. Currently, the EU allows the exchange of patient summaries and ePrescriptions. The goal is to also have medical images, laboratory results and reports, and hospital discharge reports available for exchange across the EU.

Figure 16. Hot spot areas of daily life crossing the country borders in Nordic-Baltic countries

In the baseline study, certain border regions in the Nordic and Baltic countries were identified as areas of close cross-border cooperation, where daily life revolves around working, living, and consuming services on both sides of the border. Cross-border data exchange is particularly vital in border regions where the nearest healthcare facilities may be located on the other side of the border. Consequently, there is often an increased amount of collaboration between the countries’ clinical groups and hospitals.

The cross-border sharing of patient data digitally would significantly improve the availability of data. From the professionals’ point of view, the improved availability of data correlates with patient safety. It is noteworthy that the needs and requirements for health data exchange depend on the nature of cross-border mobility in the region in question.

Based on the cost-benefit analysis of healthcare data exchange,

In addition to cross-border commuting, several other reasons for mobility were further highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, including family ties and property ownership. Countries closing their borders and only allowing access on very restricted grounds that often differed between the countries caused further frustration in these areas, for the tightly integrated way they were built and strongly relied on the possibility to cross the border whenever needed.

Cross-border healthcare data exchange has its core objective in continuity of care. It includes both planned and unplanned care. Planned care refers to aspects such as intentionally traveling to another country to access specialised healthcare services where unplanned care is more of an emergency or sudden a need for healthcare during a stay in another country. For both planned and unplanned care, the capability to reliably transfer health data on personal medication, allergies, and other vital information to another country enhances the safety and continuity of care for the patient. In addition, the smooth exchange of health data can reduce the number of unnecessary double-testing and procedures, and therefore also contribute to lowered healthcare costs.

According to Laitinen, Virkki and Porkka (2022),

https://www.duodecimlehti.fi/xmedia/duo/duo17059.pdf (in Finnish)

Understanding the diverse needs of citizens for cross-border data-exchange

The results and conclusions of the cost-benefit analysis of cross-border healthcare data exchange in areas of close cross-border cooperation in the Nordic and Baltic countries offer a wider understanding of the phenomenon—how common it is in numbers, what the needs of the people are who cross borders as a part of their daily life, and how important cross-border data exchange is as a prerequisite for mobility for all.

From an equality point of view, it is essential to ensure the different user groups are accounted for and that they can access the kind of health data that is necessary for them. Gender equality is generated where ordinary decisions are made, resources allocated, and norms created.

The main objective is to ensure continuity of care – including both planned and unplanned care. As an example, where a sudden need for medical care occurs whilst traveling abroad, the transfer of relevant data should follow the patient when the care continues again at the place of habitual residence.

Acting on behalf of another person is one example of national development that would require some more European collaboration as currently the authorisation works differently in different member states. This causes potential challenges for example when a parent would need to act on behalf of their child in case of an emergency while in another EU country. Currently, the original authorisation in the child’s home country might not be visible to the authorities in another EU country and the process may be delayed while the required evidence of authorisation can be arranged.

The Nordic Council of Ministers’ programme for cooperation on disability issues between 2023 and 2027 has been endorsed. One of the focus areas is raising awareness of and breaking down barriers to freedom of movement across country borders. This is a priority area within Nordic co-operation. The EU is also making special efforts to break down barriers for people with disabilities. Activities in this focus area promote freedom of movement for people who are at risk of being hindered by different barriers due to various laws, rules, and administrative practices in the Nordic countries.

In addition, cross-border mobility of health data may contribute to better access to services at a lower cost, as the nearest pharmacy or hospital might be across the border.

Increased need for cross-border exchange of data

There is an increased need for cross-border exchange of healthcare data in the areas of close cross-border collaboration. These areas share many characteristics but as we identified in our analysis, there are several factors that affect the amount and nature of cross-border mobility, as well as collaboration between the countries. In the areas where distances are long and the population density is low, countries need to collaborate more closely and share resources to provide the necessary services, also in terms of healthcare. The extensive collaboration between the ambulance services of Finland, Sweden and Norway in the Torne Valley and the collaboration between Estonia and Latvia around the Valka-Valga region are great examples of such collaboration.

See chapter 4.4 Case examples of exchange of healthcare data

Therefore, despite regional differences, we found that there is an increased need for cross-border exchange of healthcare data and overall access to healthcare services across borders in most of the examined areas. Similar areas for close cross-border collaboration have been identified between many other European countries, which implies that there may be a more substantial need for cross-border exchange of healthcare data across the EU than expected. This is especially likely if previous estimations of needs have been based on use cases related to tourism.

Expected benefits

The benefits to be gained from the cross-border exchange of healthcare data are clear and supported by previous research. The benefits have been studied on several occasions over the years, and in accordance with the results of this study, it has been clear for some time that there is a strong need for exchanging healthcare information between the Nordic and Baltic countries. The most cited benefits include improved patient safety and quality of care, as well as patient access to care, especially in terms of unplanned urgent care. Additionally, improved cross-border exchange of healthcare data could result in cost savings due to a decrease in manual requests for information processes, as well as in the form of not needing to perform unnecessary double tests and scans.

Cost-benefit analysis of cross-border healthcare data exchange in the Nordic and Baltic countries, p. 30

4.2. Frameworks, initiatives, and standards

This chapter assesses the most relevant standards and frameworks in the field of cross-border data exchange in health services. It must be noted that the European Health Data Space (EHDS) and the European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDI Wallet) (see EUDI Wallet on page 14 for more information) are currently only at a stage of legislative proposal, and even after the negotiations and consultations on the new regulation, there may be room for different means of implementations in practice. In the following chapter, the Handbook will shortly introduce the essential frameworks and initiatives related to cross-border healthcare data exchange. These standards should be considered as the basis for work. (See chapter 2.1 Standards and frameworks for more information).

The European Health Data Space (EHDS)

EU citizens’ rights to access and control of their healthcare data, as well as free mobility of information are considered to be some of the key benefits of the EHDS. Patient access to their own electronic health records (EHRs) is becoming an essential part of healthcare systems. According to the Commission’s 2030 Digital Compass, by 2030, all citizens could have access to their electronic medical records, also 80% of citizens could use an eID solution.

The European Health Digital Service Infrastructure (eHDSI), also known currently as the MyHealth@EU Infrastructure is a central initiative for developing service infrastructure for cross-border health data exchange between the EU countries, and it is part of the EU4Health programme

Contact points of each Member State create the foundation for information exchange in healthcare services. Each of these contact points must perform the minimum requirements for interoperability. On the other hand, each of these contact points are the implementing entity, who integrate the national healthcare services according to eHDSI standards and prepare it for exchange.

eHDSI enables the exchange of ePrescriptions and eDispensations as well as patient summaries electronically between the EU countries, through National Contact Points. Since the maturity of national solutions is variable across the EU, the focus of the MyHealth@EU has been on including only most necessary requirements. Additional desirable features that could improve the infrastructure have been identified and included in an EHDS proposal. The consistent and synchronised implementation of services across different countries has been challenging, but the implemented services are in operational use while still maintaining security and safety.

Finland and Estonia are currently the only two Nordic-Baltic countries successfully sharing ePrescription information using the eHDSI.

The European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDI Wallet)

One of the EUDI Wallet pilot projects, POTENTIAL

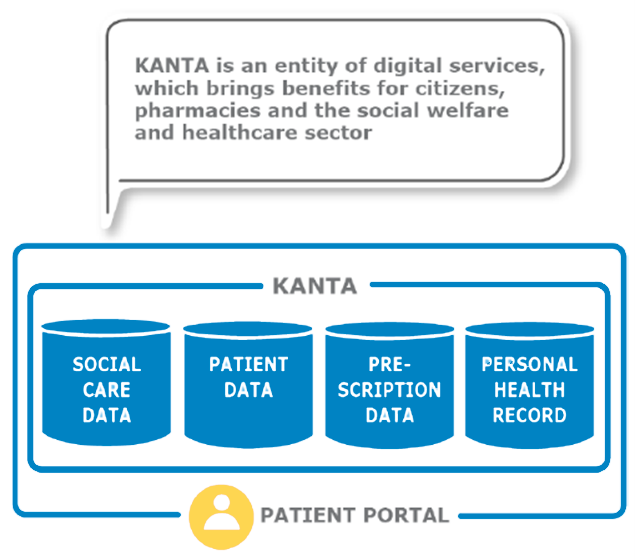

Interoperability is the most essential element. An illustration of this is the nationwide Finnish Kanta Services, which incorporates technical solutions to enable system interoperability, especially in Europe. Commonly accepted international standards should bear high priority both in operation and system design. In addition, it is feasible for all parties to aim for active participation, and to share one’s own knowledge and insights.

A patient summary is an identifiable dataset of essential and understandable health information that includes the most important clinical facts. The dataset is intended mainly for unplanned care; however, it can be used to provide planned medical care in the case of citizens mobility. The patient summary is a vital objective of the free movement of patients across the borders.

Standards are an important enabler of health data exchange. However, standards do not include all aspects of interoperability in the situation where they are implemented. Utilising standards in data exchange improves the interoperability of systems which support various work processes.

A patient summary is a standardised set of data that includes the most important health and care related facts required to ensure safe and secure healthcare. In international patient summary (IPS) standards, a patient summary is defined as an electronic health record extract containing essential healthcare information about the subject of care.

International Patient Summary Implementation Guide: https://build.fhir.org/ig/HL7/fhir-ips/

The IPS is building a bridge between the “home” health and care environment of the patient and any other place where the patient needs to visit a clinical professional, especially across borders. The construction of the IPS involves several standards and specifications.

International patient summary standards and specifications include guidelines and recommendations, CEN content standards, HL7 implementation guides, and SNOMED standard medical terminology, which supports semantic interoperability, and an IHE integration profile to guide implementation and enhance conformance.

Mykkänen. IPS – Standardit ja hankkeet. 18.5.2021. https://thl.fi/documents/920442/6748650/20210518_3_IPS-SoteTAOhry-Juha+Mykk%C3%A4nen.pdf/8a0fbc6c-f6d4-674a-ca2c-95b2131d8e40?t=1623991691391

The European Electronic Health Record Exchange Format (EEHRxF) is a standardised framework designed to facilitate the secure exchange of electronic health records between different healthcare systems in Europe. It is designed to help improve the interoperability of health records in the EU Member States. It also supports the European strategy for data and creation of the European Health Data Space by scaling up the secondary use of this data in research, innovation, and regulatory activities. It establishes uniform data structures, coding systems, and protocols to ensure consistency in exchanging electronic health records. It provides an infrastructure for secure data exchange, for applications including the European Patient Summary and ePrescription.

Currently, the main challenge is individual code systems varying between Member States, which prevent advanced interoperability. Mapping or harmonization of individual code systems to common European code systems is therefore a subject that needs closer attention. Moreover, it is important that Member States are encouraged to participate in eHDSI trial periods, where it is possible to get feedback from the professionals in another Member States that supports the development.

4.3. Networks and stakeholders

The majority of the expert interviews stated that the development of the cross-border data exchange aims to achieve active cooperation between stakeholders. This chapter provides an insight into the key networks and stakeholders who could be utilised when working on this topic. Well-functioning information systems on the national and local level are the starting point, which function as a foundation for further development for international integration, harmonisation, and co-operation. Ultimately, these same administrative bodies and developers are often engaged in subsequent cross-border projects, or national and regional infrastructure is reused for international information exchange. The healthcare sector has a strong foundation through the European regulatory framework, which is further expanding through the regulatory proposal for European Health Data Space regulation. This proposal aims to develop cross-border healthcare data exchange.

The eHealth Network

Currently the subgroups of the eHealth Network play a preparatory role, and they are focusing on producing evidence and recommendations to support the network’s activities. The activities are financed through various EU-wide projects. For example, the X-eHealth project intends to produce a guideline on the exchange of electronic health records that ultimately needs to be approved by the eHealth Network.

The eHealth Network may be perceived as relatively complicated due to the multiplicity of actors involved. Both decision-making bodies as well as the preparatory subgroups are important functions of the network. Active participation in the network’s functions is essential for ensuring coherent EU-level guidelines and regulations on health data exchange and use.

The eHealth Network (eHN) consists of members from the European Commission and from all EU Member States and Norway. Norway is an observer, and the Chair of eHealth Network may give observer status to national authorities responsible for eHealth of EEA/EFTA countries and of accession countries. The eHealth Network is voluntary to all Member States, and it provides a platform of Member States’ authorities dealing with eHealth. The eHealth Network meets twice a year.

The eHealth Network’s subgroups:

- The eHealth Network Subgroup on Semantics (Semantic SG) prepares recommendations on the use of certain standards against established criteria and based on the guidelines for accepting semantic resources as European semantic standards. It administers the Common European Network of Health Semantic Services. Additionally, the Subgroup on Semantics provides the strategic decisions regarding semantics to eHealth Network.

- The eHealth Network Technical Interoperability Subgroup (Tech IOP SG) aims to address technical interoperability.

- The eHDSI Member States Expert Group (eHMSEG) is a permanent subgroup

- The eHealth Operational Management Board (eHOMB) The eHealth Operational Management Board (eHOMB) is composed of representatives of internal services of the European Commission and the eHMSEG Chairs. It oversees the provision of services and takes tactical and operational decisions on the eHDSI.

All aspects affecting the data exchange are made interoperable. Additionally, the awareness on matters relating to cross-border data exchange is important. Belief in EU-wide capability is one key aspect in this respect, and people holding authority in the decision-making organization must understand the benefits in the big picture. Only then the interoperability may be reached.

The EU4Health Programme (EU4H)

The X-eHealth project aims to build the foundations for advancing the integration of eHealth services into the already-existing European Cross-Border Patient Summary. It aims to do so by developing the basis for a workable, interoperable, secure, and cross-border Electronic Health Record Exchange Format (EEHRxF) and accelerate its implementation through the standardisation and harmonisation of health data.

DG-SANTE3 (Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety) develops and carries out the Commission’s policies on food safety and public health. Among others, DG SANTE aims to build a strong European Health Union to protect and improve public health, and to ensure Europe’s food is sustainable and safe.

The Nordic Committee of Senior Officials for Health and Social Affairs (ÄK-S) of the Nordic Council of Ministers (NCM) established the Nordic Council of Ministers’ eHealth Group in 2011 to ensure knowledge transfer between the Nordic countries, and to help to strengthen the global leadership position of the region in the eHealth area.

The scope of the eHealth Group emphasises the current political priorities at national levels and in the EU framework. The eHealth Group is both a central forum for knowledge transfer between the Nordic countries as well as a platform for the joint formulation of strategic initiatives to enable communication of a common Nordic view.

The group has a rotating chairing country. Finland is the chair during 2023–2024, and the goals set for the period are

- Sharing of knowledge and best practices in e-health in Nordic countries, around issues like digital health structures in different Nordic countries, quality of data, interoperability at all levels of eHealth services, supporting the work of professionals through digitalisation

- Strengthening cooperation on relevant topics

- Influencing EU level development with a common Nordic voice

- Strengthening of the Nordic position in EU cooperation making it possible to stress Nordic priorities

There are two sub-groups operating under the Nordic e-Health Group: the eHealth Standardisation group and the Nordic Council of Ministers eHealth Research Network.

The main tasks of the eHealth Standardisation group are to serve as an arena for enhancing Nordic understanding, knowledge sharing, and to engage in collaboration on specific eHealth standardisation issues, and participation and positioning towards the ongoing international work on standardisation at the European and global level.

The Nordic Council of Ministers eHealth Research Network (NerN) works on eHealth indicators to advance the eHealth monitoring activities and systems in the Nordic countries. The work should also be shaped by the Nordic objectives and actions: the Nordic region being the most sustainable and integrated region in the world. The work should head towards systematic eHealth monitoring and appropriate collaboration with the OECD, EU and WHO. Primary objective: To develop and pilot an updated set of indicators that can be used to assess and compare the impact of national-level digital health programmes in the Nordic countries.

4.4 Case examples of exchange of healthcare data

This chapter provides and insight of case examples of exchange of healthcare data between Finland and Estonia, with a case example of extensive collaboration around the Valka-Valga region, a case example from the region between Finland and Sweden, and a case example from the Nordic Baltic Interoperability project case Alva.

Case: ePrescription in Finland and Estonia

Within the healthcare sector, Finland and Estonia are currently the only two Nordic-Baltic countries that are successfully sharing ePrescription information across borders through eHDSI. Finnish ePrescriptions have been used in Estonia already since 2019,

The successful adoption of cross-border ePrescription and eDispensation has been made possible by the pre-existing eHealth services and data infrastructures and continuous development in both countries. Cross-border health data exchange would be extremely difficult without a functioning nation-wide health service infrastructure. In addition, the EU Commission’s financial assistance for Member States to set up cross-border health services is also granted with the pre-requisite that certain national services enabling cross-border health data exchange are already in place. The Finnish Kanta Services and Estonia’s equivalent, eHealth Estonia, are examples of such system; they are sets of national digital health and social care record systems that provide citizens and healthcare professionals with secure access to patient information and health records. These systems share similar goals for their functions but are tailored to the specific needs and contexts of their respective countries, with differences in implementation, features, and operation. Recent research examining the implementation of the Kanta Services in Finland has described the central building blocks of such a large-scale nationwide development process

Figure 17. Finnish Kanta, core services

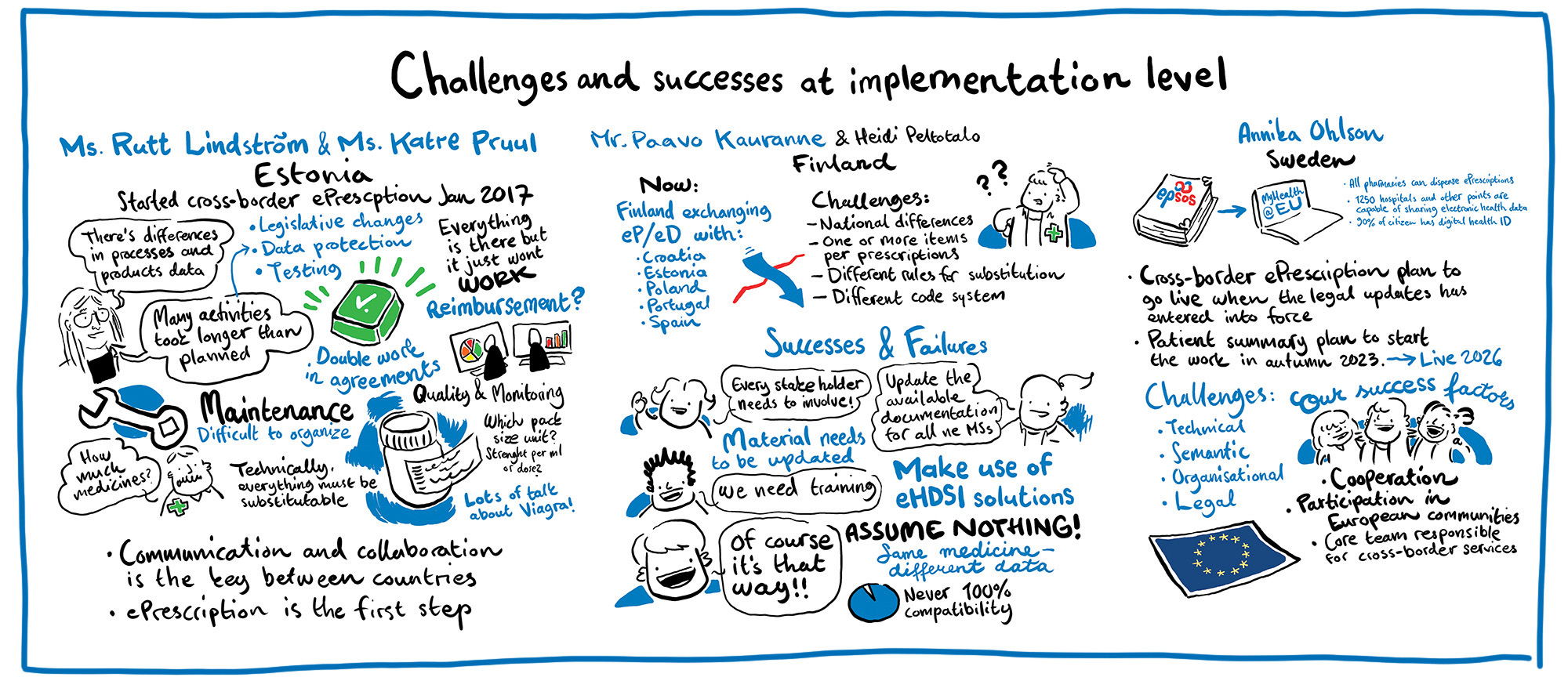

As a part of this work package, a seminar on the successes and challenges in the implementation of cross-border ePrescriptions between Finland and Estonia was organised. The following section presents the lessons learned from the workshop.

Lessons learned from Finland on the implementation of ePrescriptions

Nella Savolainen, Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Lessons learned from Finland on the implementation of ePrescription/MyHealth@EU 29.6.2022

- An existing centralised health service infrastructure, such as the Kanta Services in Finland, has made the implementation of cross-border services easier, because a centralised service makes it possible to implement the solution only once.

- Ensuring interoperability between national codes and the common EU code lists is difficult.

- Testing periods are challenging and they require resources and time. Currently, the use of the ePrescription service is rather limited, yet it requires a lot of work to implement and maintain it.

- Progress is slow, and even minor changes take time and resources.

- The standardised development cycle enables controlled progress and the development of services. Also, the cooperation between representatives of other Member states mainly worked well, and assistance is available on request from the eHealth Network.

- Consistent mapping, measuring and documentation of the process has enabled successes in implementing services.

- Training and information materials for professionals are crucial to bridge the gap between national and cross-border practices.

- Information about cross-border ePrescriptions must be provided to citizens (see examples of the Kanta Services instructions for citizens).Examples of Kanta Services instructions

- Cultural change is needed for health professionals to encourage adopting behaviors and mindsets that are consistent with cross-border requirements and processes, and for citizens to be more actively involved in the process.

- It is highly unlikely to achieve 100% compatibility of services; aim for the highest possible compatibility!

- Technical implementation is not enough; understanding the processes and functioning of ePrescription and eDispensation in other countries is key. Constant communication, collaboration and agreements between countries are needed

- Although challenging, testing of services should be done in cross-border context in addition to national context to identify user cases and potential pitfalls

- It is important to constantly monitor the experiences of users and professionals

Figure 18. Live illustrations from a workshop on challenges and success at implementation level

Customers and professional experiences on ePrescriptions

Related use cases and end-user benefits of cross-border ePrescription use have been studied over the past few years (e.g., Jõgi, 2021

Jõgi, R. (2021). Cross-Border e-Prescriptions – the First Experience of the Pharmacists in Estonia and Finland

Kangosjärvi et al, 2023: https://dosis.fi/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/090-107_Dosis_123_Kangosjarvi.pdf

Jõgi et al, 2023: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37014689/

When asking customers, most respondents in the study have been satisfied with the ePrescription, stating that being able to purchase prescription medicines across the border made short- and long-term traveling between the countries easier and more accessible.

Kangosjärvi et al, 2023: https://dosis.fi/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/090-07_Dosis_123_Kangosjarvi.pdf

When asking pharmacists in both Estonia and Finland, most agreed that the cross-border ePrescription system improved access to medications. However, interfering factors, such as ambiguities or errors and technical problems in the system, can reduce access to medications. The respondents had received sufficient training and were informed of the guidelines; however, they felt that the content of the guidelines could be improved.

Jõgi et al, 2023: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37014689/

ePrescription in numbers

In Finland 2022 cross-border dispensations:

- 5000 foreign ePrescription dispensing events in Finland

- 9000 Finnish ePrescription dispensing events abroad

Figure 19. ePrescription in numbers, Paavo Kauranne, presentation in Tallinn 2023

Case: Twin cities of Valga (Estonia) and Valka (Latvia)

Another case example provides insight to the cross-border use of services. Valga and Valka are in the border area between Estonia and Latvia. The cities are working towards developing the two cities to become one for its inhabitants, regardless of their nationality.

Case: Torne Valley (Finland and Sweden)

This case example takes place in the border region between Finland and Sweden, centred around the twin cities of Tornio and Haparanda. The Torne Valley area has special characteristics by the everyday phenomenon of working and purchasing goods and services on both sides of the border.

Characteristics of healthcare services in the Torne Valley area:

- Crossing the border to access private healthcare services is common in the area, however utilising public healthcare services across the border for planned care is less common

- The area has a high degree of collaboration between emergency services of different countries to ensure both patient safety as well as timely and efficient delivery of the services

Especially in the Northern areas of lower popular density, such as the Torne Valley area, ensuring smooth daily life and on the other hand reasonable use of resources requires close cross-border collaboration. Usually, the distances between patients and care providers are long, and thus, the emergency services have an increased need to collaborate closely. The ability to share information between the responding units and hospitals in the two countries is crucial for improving patient safety in the field. Patient safety would be improved further if the patient’s medical history, such as previous medical procedures, diagnoses, and allergies were available to the care provider multi-nationally. This is especially true in terms of unplanned, urgent care. Having adequate information on the patient’s medical history would also make it easier to provide high quality of care, which would help to increase trust amongst patients and ultimately result in better service.

One of the best practices is to do a lot of testing with different countries. It helps identify challenges especially language related. Also, when implementing new services, you must know your users – find out whether there are people who would use the services and whether there are other countries using it.

- From Sweden to Finland: 50-60 per year

- From Finland and Norway to Sweden: 100-150 per year

Figure 19. Case: Torne Valley. Ambulance missions in the Torne Valley area

The ePrescription service is not yet in use between Finland and Sweden, although access to ePrescriptions would significantly help to reduce the number of errors concerning medication purchased abroad and thus offer better overall medication safety. It would also improve the accessibility of healthcare, as well as better commitment to medical treatment when staying abroad, or residing in border areas. Developing cross-border healthcare data exchange would improve the overall cross-border mobility for all groups, including those with disabilities or chronic conditions that require regular monitoring or medication, for example in terms of being able to work or study across borders.

Case: Alva

To illustrate the possibilities and challenges that the sharing of health data in the Nordics presents, the Nordic Interoperability Project (N!P) created the Alva case. Alva is a Swedish diabetes patient in the near future, and we follow her journey through the Nordic region and see how shared health data is affecting her travels.

Through these above-mentioned interoperability showcases it is possible to spark discussions and better understand the different needs of all citizens in different stages of life. It is essential to ask about and understand the different requirements of user groups to avoid creating realities that are discriminatory for some. Cross-border mobility is no exception and it represents a situation where all people must have equal power and opportunities to influence their lives and contribute to the development of society. Although matters of health data exchange are often discussed in largely technical terms, the solutions are developed ultimately to serve people equally and make their lives easier.

Cross-border mobility of health data enables more equal opportunities for all, but only if it is designed and implemented in a way that serves all its user groups without leaving anyone behind. Showcases such as Case Alva serve to remind that the goal of development work is to enable all patients to live and act in an open, seamless, cross-border healthcare ecosystem.

Figure 20. Screenshots from the webpage of project Nordic Interoperability, Case Alva

4.5 Key take-aways

1. Functioning and interoperable national and regional systems

Well-functioning national information systems are the starting point and foundations for further development for international integration, harmonisation, and co-operation. A policy-level commitment and investment in the process is vital to ensure successes in national and cross-border implementation. Ultimately, the same administrative bodies and developers are often engaged in subsequent cross-border projects.

Long-term development work is needed both on the national and on international level, and smooth cross-border health data exchange requires both national and international cooperation. There are many actors involved in health data exchange on a national level, but for international health data exchange especially the national authorities play a big role in driving the development forward. Regional cooperation in development is essential in ensuring interoperability.

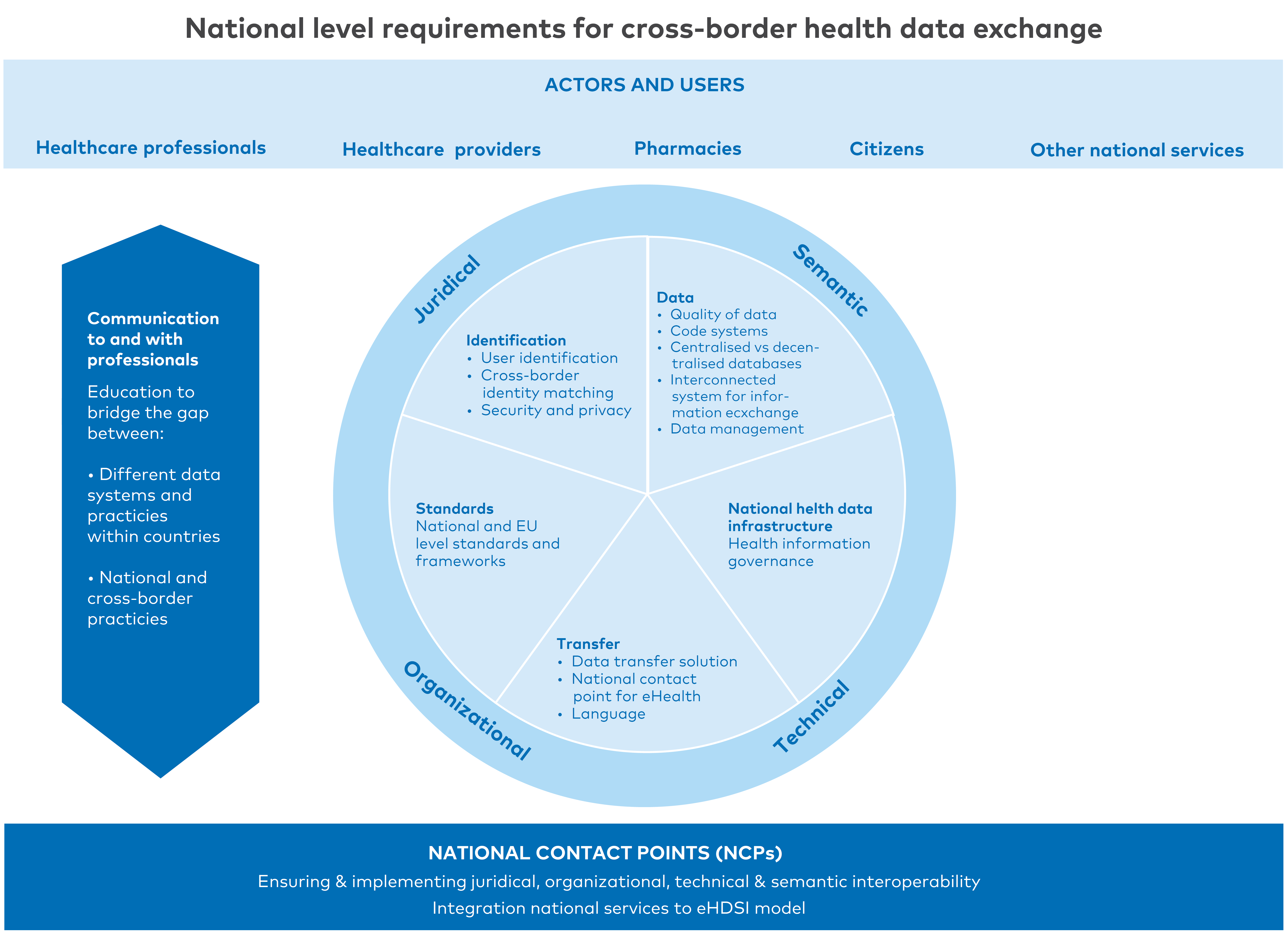

2. Overcoming barriers to developing cross-border health data exchange

Multiple factors are slow down, prevent, or constrain data access and exchange of health data. These were identified in the baseline study using the requirements on the European Interoperability Framework (EIF).

See chapter 2. The Ballpark and the key players

The key legal barriers slowing down, preventing, and constraining data access and exchange of ePrescriptions and patient summaries, are data privacy and information security-related challenges. Additionally, many countries do not have national legislation that supports cross-border health data exchange. Therefore, aligning national laws with cross-border services and identifying the need for amendments in the national legislation to ensure harmonisation on the national and EU levels creates the basis for smooth cross-border operability. Finally, political investments and prioritisation are needed to create or complement the national legislation concerning cross-border health data exchange.

It is worthwhile encouraging relevant authorities to actively participate in different types of EU-wide projects, such as joint actions. EU-projects should be utilized to support the development of relevant services and impact choices made at the EU level, as these projects are great avenues to launch initiatives and influence the outcomes. In addition, it is recommended that parties to these projects have strong willingness and capability to achieve the objectives, as this makes sure the outcomes are worth the effort and are of high quality.

In addition, available human resources and financial issues for practical development work are significant organisational barriers. Information sharing between countries about different funding options and instruments available can be beneficial. Furthermore, establishing a national core team responsible for cross-border services can be beneficial for more effective coordination of and ensuring interoperability in national and cross-border services.

Annika Ohlson, Swedish eHealth Agency, Sweden – Cross-border services 22.8.2023

Semantic work is the core when it comes to smooth cross-border health data exchange. Sufficient alignment and translation of terminologies, code systems and mappings both nationally and internationally are needed to have enough detail in data sets that are commonly understood in different countries. The eHealth Digital Services Infrastructure (eHDSI) especially seems to be a key initiative for the cross-border exchange of ePrescriptions and patient summaries. Besides the semantics, patient-accessible electronical health records (PAEHR) and e-identification are also important themes that need to be considered in future development work.

Benchmarking, knowledge sharing, and common prioritisation between countries are important aspects for further development. Common international standards are key to successful data exchange, and it applies to multiple aspects of health data exchange, including data privacy protection and security methods, encryption, identity management and identification, technologies, and semantic issues.

Concrete actions to improve knowledge sharing could be to gather statistics or knowledge on what kind of information is found in different countries. Measuring and documenting processes provide essential information to further develop national and cross-border services and are a key to success.

Vesa Jormanainen, Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Challenges, and successes at policy level: electronic prescription and Nationwide Kanta Services in Finland since 2010 22.8.2023

See chapter 2.2 Networks and Stakeholders

Communication, training and briefing materials provided to the professionals play a key role in describing the similarities between national workflows and the corresponding eHealth@EU workflows, paving the way to the smoother cross-border operations in daily practice.

3. Effective collaboration between Nordic and Baltic countries

Effective collaboration between the Nordic and Baltic countries is key when implementing cross-border health data services. Utilising the existing platforms and creating opportunities for dialogue are important for facilitating learning and enabling successes in cross-border health data exchange. Furthermore, fostering a common Nordic-Baltic voice is valuable in encouraging closer Nordic cooperation in EU-policies.

Some Nordic and Baltic cooperation structures have already been established to strengthen collaboration on digitalisation, but cross-border development would benefit from further strengthening the collaboration in the region. Development activities are potentially significantly more productive when putting our collaborative strengths together and building interoperable processes and systems.

4. The role of professionals in the implementation of the operational services

In addition to policy-level commitment and investment to cross-border health data exchange, the role of professionals at the actual implementation level testing and developing the services is essential. Their feedback and experiences should be followed-up and used continuously in further development of the services.

Paavo Kauranne, Kela, Cross-border eP/eD with Finnish Kanta-services 22.8.2023

Cultural change needs to be supported in the daily operations of professionals working with cross-border health data exchange. They need to be encouraged to adopt behaviours and mindsets that are consistent with new requirements and processes.

Comprehensive training and available up to date information and materials on cross-border health data practices are essential to ensure the capacity of health professionals to implement and provide cross-border services, and to bridge the gap between national and cross-border practices.

5. The role of citizens

In all planning and development of cross-border health services, it is central to recognise the citizens role as active actors in creating and using health data, not just targets of data use.

On the national level it is important to ensure the participation of citizens and patients and ensure that citizens’ have access to more and higher-quality health information, e.g. by developing a health information portal, ensuring citizens’ access to their own patient records, health information and log data. It further important to develop electronic services (booking of appointments, electronic discussions, electronic document transfer, online consultation) as well as enhance interactive electronic services.

In addition to health professionals, citizens must also have the relevant and up to date information on cross-border health services and how their data is handled and available to them, to be able to be actively involved in their care. Cross-border health data exchange adds another layer to health service and health data utilisation, and it is crucial for citizens to actively give or deny consent for cross-border health data sharing for the implemented services to function efficiently.

It is also important to monitor the attitudes and experiences of citizens regarding data sharing. For this reason, the project “Achieving the World’s Smoothest Cross-Border Mobility and Daily Life through Digitalisation” supported the publication of the results of the NCM project titled, “A Nordic survey to monitor citizens’ use and experience with eHealth”

Eriksen J, Hjermitslev C, Vehko T, Harðardóttir G, Koch S, Faxvaag A, et al. (2023). A Nordic survey to monitor citizens’ use and experience with eHealth. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers.

Figure 21. National level requirements for cross-border health data exchange

References

- Nordic Council of Ministers. (2021). Baseline study of cross-border data exchange in the Nordic and Baltic countries. Available: https://www.norden.org/en/publication/baseline-study-cross-border-data-exchange-nordic-and-baltic-countries. Cited 7.7.2023.

- Valtioneuvosto. (2015). MyData – A Nordic Model for human centered personal data management and processing. Available: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-243-455-5. Cited 29.8.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). eHealth Network. Available: https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/eu-cooperation/ehealth-network_en. Cited 29.8.2023.

- eHealth Network. (2023). Guideline on the electronic exchange of health data under Cross-Border Directive 2011/24/EU. Available: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-06/ehn_guidelines_eprescriptions_en.pdf. Cited 15.5.2023.

- Kela. (2023). System for electronic exchange of information EESI. Available: System for electronic exchange of information EESSI | About Kela | Kela. Cited. 28.8.2023.

- European Commission. (2013). Towards a more digital social security coordination: Commission proposes steps to make it easier for Europeans to live, work and travel abroad. Available: Towards a more digital social security coordination: Commission proposes steps to make it easier for Europeans to live, work and travel abroad - Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion - European Commission (europa.eu). 8.9.2023.

- World’s Smoothest Cross-Border Mobility and Daily Life Through Digitalisation. (2023). Cost-benefit analysis of cross-border healthcare data exchange in the Nordic and Baltic countries. Available: https://wiki.dvv.fi/display/WSCMD?preview=/117377490/235526906/Cost-benefit%20analysis%20of%20cross-border%20healthcare%20data%20exchange%20in%20the%20Nordic%20and%20Baltic%20countries_31052023.pdf. Cited 28.7.2023.

- Laitinen, T., Virkki, A. & Porkka, K. (2022). FinOMOP: terveystietojen kansainvälinen harmonisointi. Kansainvälisen harmonisointistandardin käyttöönotto on keskeistä suomalaisten terveystietojen tehokkaalle yhteiskäytölle. Duodecim. Available: https://www.duodecimlehti.fi/xmedia/duo/duo17059.pdf. Cited: 5.6.2023.

- Knosp, B. (2020). Informatics Playbook – Chapter: 6 Understanding Data Harmonization. Available: https://playbook.cd2h.org/en/latest/chapters/chapter_6.html

https://playbook.cd2h.org/en/latest/index.html. Cited: 5.6.2023.

- Nordic Welfare Centre. (2023). Nordic Programme for Co-operation on Disability Issues 2023–2027. Available: https://nordicwelfare.org/en/disability-issues/nordic-programme-for-co-operation-on-disability-issues-2023-2027. Cited 15.8.2023.

- Nordic Welfare Centre. (2023). Nordic Programme for Co-operation and disability issues 2023-2027. https://nordicwelfare.org/en/disability-issues/nordic-programme-for-co-operation-on-disability-issues-2023-2027/. Cited 28.7.2023.

- See chapter 4.4 Case examples of exchange of healthcare data

- World’s Smoothest Cross-Border Mobility and Daily Life Through Digitalisation. (2023). Cost-benefit analysis of cross-border healthcare data exchange in the Nordic and Baltic countries. Available: https://wiki.dvv.fi/display/WSCMD?preview=/117377490/235526906/Cost-benefit%20analysis%20of%20cross-border%20healthcare%20data%20exchange%20in%20the%20Nordic%20and%20Baltic%20countries_31052023.pdf. Cited 28.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2022). European Health Data Space. Available: https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/european-health-data-space_en. Cited: 15.5.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). Europe’s Digital Decade: digital targets 2030. Available: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/europes-digital-decade-digital-targets-2030_en. Cited 28.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). EU4Health programme 2021-2027 – a vision for a healthier European Union. Available: https://health.ec.europa.eu/funding/eu4health-programme-2021-2027-vision-healthier-european-union_en. Cited 29.9.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). Electronic cross-border health services. Available: https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/electronic-cross-border-health-services_en. Cited 29.9.2023

- European Commission. (2023). EU Digital Identity Wallet Pilot Implementation. Available: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/eudi-wallet-implementation. Cited 28.7.2023.

- POTENTIAL. (2023). Project website. Available: https://www.digital-identity-wallet.eu/. Cited 28.7.2023.

- DC4EU. (2023). Project website. Available: https://www.dc4eu.eu/. Cited 28.7.2023.

- HL7. (2022). International Patient Summary Implementation Guide. Available: https://build.fhir.org/ig/HL7/fhir-ips/. Cited 28.7.2023.

- IPS. (2023). The International Patient Summary. Available: https://international-patient-summary.net/. Cited 15.5.2023

- Mykkänen, J. (2021). International Patient Summary – Potilastietojen yhteenvedot – standardit ja hankkeet. Available: https://thl.fi/documents/920442/6748650/20210518_3_IPS-SoteTAOhry-Juha+Mykk%C3%A4nen.pdf/8a0fbc6c-f6d4-674a-ca2c-95b2131d8e40?t=1623991691391. Cited: 15.5.2023.

- Health Information and Quality Authority. (2015). ePrescription dataset and clinical document architecture standard. Available: CDA ePrescribing Draft Standard for Trial use (hiqa.ie). Cited 29.9.2023

- HL7 International. (2023). CDA Release 2. Available: HL7 Standards Product Brief - CDA® Release 2 | HL7 International. Cited 29.9.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). Exchange of electronic health records across the EU. Available: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/electronic-health-records. Cited 28.7.2023.

- eHAction. 2023. Health Data Exchange. Available: http://ehaction.eu/interoperability-guide/health-data-exchange. Cited 19.7.2023

- European Commission. (2023). eHealth Network. Available: https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/eu-cooperation/ehealth-network_en. Cited 28.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2022). Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the council on the European Health Data Space. Available: eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52022SC0131. Cited 29.9.2023.

- MyHealth@EU. (2022). Powerpoint Presentation. Available: Présentation PowerPoint (esante.gouv.fr). Cited. 29.9.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). Electronic cross-border health services. Available: https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/electronic-cross-border-health-services_en. Cited 29.9.2023

- European Commission. (2023). EU4Health programme 2021-2027 – a vision for a healthier European Union. Available: https://health.ec.europa.eu/funding/eu4health-programme-2021-2027-vision-healthier-european-union_en. Cited 29.9.2023.

- X-eHealth. (2023). Scope of Action. Available at: https://www.x-ehealth.eu/scope-of-action/ Cited: 18.7.2023

- European Commission. (2023). Health and Food safety. Available: https://commission.europa.eu/about-european-commission/departments-and-executive-agencies/health-and-food-safety_en#responsibilities. Cited 29.9.2023.

- e-Estonia. (2019). First EU citizens using ePrescriptions in other EU country. Available: https://e-estonia.com/first-eu-citizens-using-eprescriptions-in-other-eu-country/. Cited 28.7.2023.

- Vesa Jormanainen. (2023). Large-scale implementation of the national Kanta services in Finland 2010-2018 with special focus on electronic prescription. Available: LARGE-SCALE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL KANTA SERVICES IN FINLAND 2010–2018 WITH SPECIAL FOCUS ON ELECTRONIC PRESCRIPTION (helsinki.fi). Cited. 29.9.2023.

- Nella Savolainen, Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. (2022). Powerpoint presentation: Lessons learned from Finland on the implementation of ePrescription/MyHealth@EU.

- Examples of Kanta Services instructions

- Jõgi, R. (2021). Cross-Border e-Prescriptions – the First Experience of the Pharmacists in Estonia and Finland.

- Kangosjärvi M., Koivisto A., Sääskilahti M., Timonen J. (2023). Ensimmäisiä kokemuksia rajat ylittävällä reseptillä asioinnista - kyselytutkimus Viron apteekeissa asioineille suomalaisille. Dosis 39: 90–106. (In Finnish). Available: https://dosis.fi/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/090-107_Dosis_123_Kangosjarvi.pdf. Cited 28.7.2023.

- Jõgi, R., Timonen, J., Saastamoinen, L., Laius, O., Volmer, D. (2023). Implementation of European Cross-border Electronic Prescription and Electronic Dispensing Service: Cross-sectional Survey. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37014689/. Cited 28.7.2023

- Kangosjärvi M., Koivisto A., Sääskilahti M., Timonen J. (2023). Ensimmäisiä kokemuksia rajat ylittävällä reseptillä asioinnista - kyselytutkimus Viron apteekeissa asioineille suomalaisille. Dosis 39: 90–106. (In Finnish). Available: https://dosis.fi/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/090-107_Dosis_123_Kangosjarvi.pdf. Cited 28.7.2023.

- Jõgi, R., Timonen, J., Saastamoinen, L., Laius, O., Volmer, D. (2023). Implementation of European Cross-border Electronic Prescription and Electronic Dispensing Service: Cross-sectional Survey. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37014689/. Cited 28.7.2023

- Visit Valga Valka. Website. Available: https://visitvalgavalka.com/. Cited 15.8.2023.

- World’s Smoothest Cross-Border Mobility and Daily Life Through Digitalisation. (2023). Cost-benefit analysis of cross-border healthcare data exchange in the Nordic and Baltic countries. Available: https://wiki.dvv.fi/display/WSCMD?preview=/117377490/235526906/Cost-benefit%20analysis%20of%20cross-border%20healthcare%20data%20exchange%20in%20the%20Nordic%20and%20Baltic%20countries_31052023.pdf. Cited 28.7.2023.

- Nordic Interoperability Project. Case Alva. Available: https://nordicinteroperability.com/case-alva. Cited: 15.8.2023.

- See handbook chapter 2. The Ballpark and the key players

- Annika Ohlson, Swedish eHealth Agency, Sweden – Cross-border services 22.8.2023

- Vesa Jormanainen, Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Challenges, and successes at policy level: electronic prescription and Nationwide Kanta Services in Finland since 2010 22.8.2023

- See handbook chapter 2. The Ballpark and the key players

- Paavo Kauranne, Kela, Cross-border eP/eD with Finnish Kanta-services 22.8.2023.

- Valtioneuvosto.(2007). eHealth Roadmap – Finland. Available: eHealth Roadmap – Finland - Valto (valtioneuvosto.fi). Cited: 29.9.2023.

- Eriksen J, Hjermitslev C, Vehko T, Harðardóttir G, Koch S, Faxvaag A, et al. (2023). A Nordic survey to monitor citizens’ use and experience with eHealth. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers.

- THL. (2020). Nordic eHealth Research Network (NeRN). Available: https://thl.fi/en/web/thlfi-en/research-and-development/research-and-projects/nordic-ehealth-research-network-nern. Cited: 29.9.2023.