3. Findings of work package 1: Studying in another Nordic or Baltic country

Work package 1 (WP1), in the project Achieving the World’s Smoothest Cross-Border Mobility and Daily Life through Digitalisation funded by the Nordic Council of Ministers, focused on questions of data exchange related to studying in upper secondary level education and higher education in another Nordic or Baltic country.

3.1 Supporting student mobility and digital services for studying abroad

The European Commission and the European data strategy

In the Nordic-Baltic countries the mobility of students is good but the data concerning these mobilities still moves from one country to another partly manually and requires someone to document the required information again in another IT system. Most digital services are still planned and implemented today within one country, and cross-border digital services are an exception, although it could potentially have a significant role in improving work efficiency, productivity, and even sensibility in the public sector. Trusted cross-border digital services could significantly reduce the administrative burden of both students and educational institutions.

As digitalisation advances everywhere, it is also the expectation of the citizens that digital services are available, and that they would significantly simplify the old analogical processes. Citizens interested in studying abroad in neighbouring countries or in another EU Member State expect smooth and flexible digital services before, during, and after their studies (period abroad). It is also good to recognise, that increased student mobility also lowers the threshold later of working in another country, which potentially increases the mobility of labour as well.

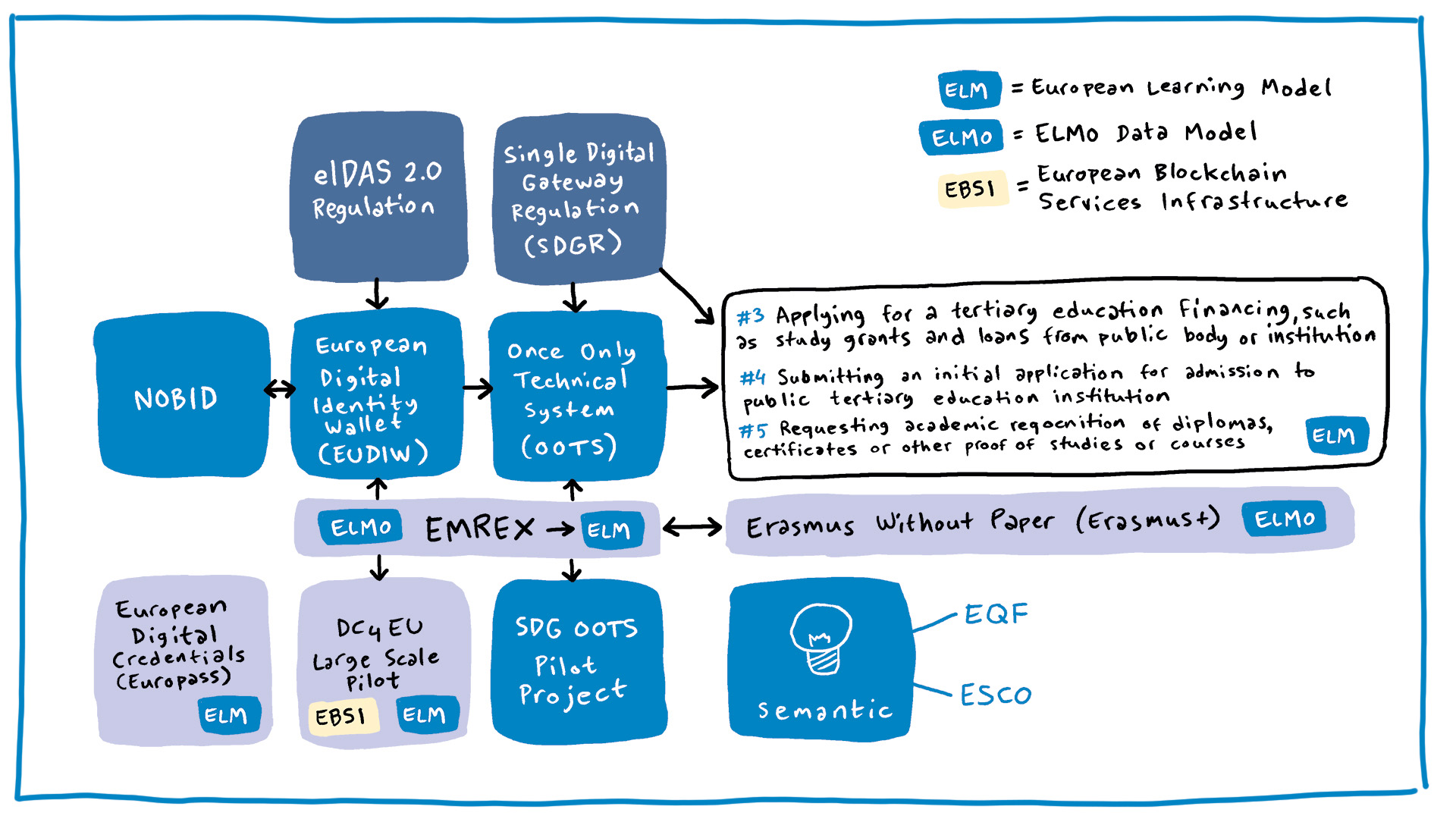

The need for cross-border digital services has been recognised on a European level and there are several ongoing projects to support student mobility and the digital services for citizens studying abroad. EMREX, European Digital Credentials, Single Digital Gateway (SDG) and its Once Only Technical System (OOTS) European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDIW) and one of its large-scale pilots Digital Credentials for Europe (DC4EU) (see more on pages 14, 15 and 16), and Erasmus Without Paper are examples of international actions that have been or will be implemented to develop digital services supporting student mobility. We will discuss these shortly in this chapter.

The range of benefits from improved interoperability and public sector cooperation is extensive: there is an obvious reduction in cost, time, energy, and unnecessary administrative burden for citizens, businesses, and the public sector itself.

3.2 European standards and frameworks of educational data

The creation of interoperable European, or even Nordic-Baltic digital services requires common standards, frameworks, and regulations. While one standard would always be the best option, different standards can coexist

The level of digital maturity varies between countries, and interoperable solutions are presently deficient. Currently, possibly the most substantial challenge is accepting the incompleteness as part of any interoperable digital services development project. European Commission is seriously working on regulation and standards in several fields, and funding for development projects building common building blocks and other reusable materials, products, and services can be obtained from several sources (see chapter 2.1 Standards and frameworks).

See handbook Chapter 2.3 Potential funders

We believe we have reason to state that while one standard would always be the best option different standards can coexist. There is always different scope for the different initiatives going on, and with that also at least partly different needs for data formats.

Figure 8. Connections between standards, data models, and current pilot projects in the context of cross-border data exchange of educational data (conception by Work package 1: Studying in another Nordic or Baltic country

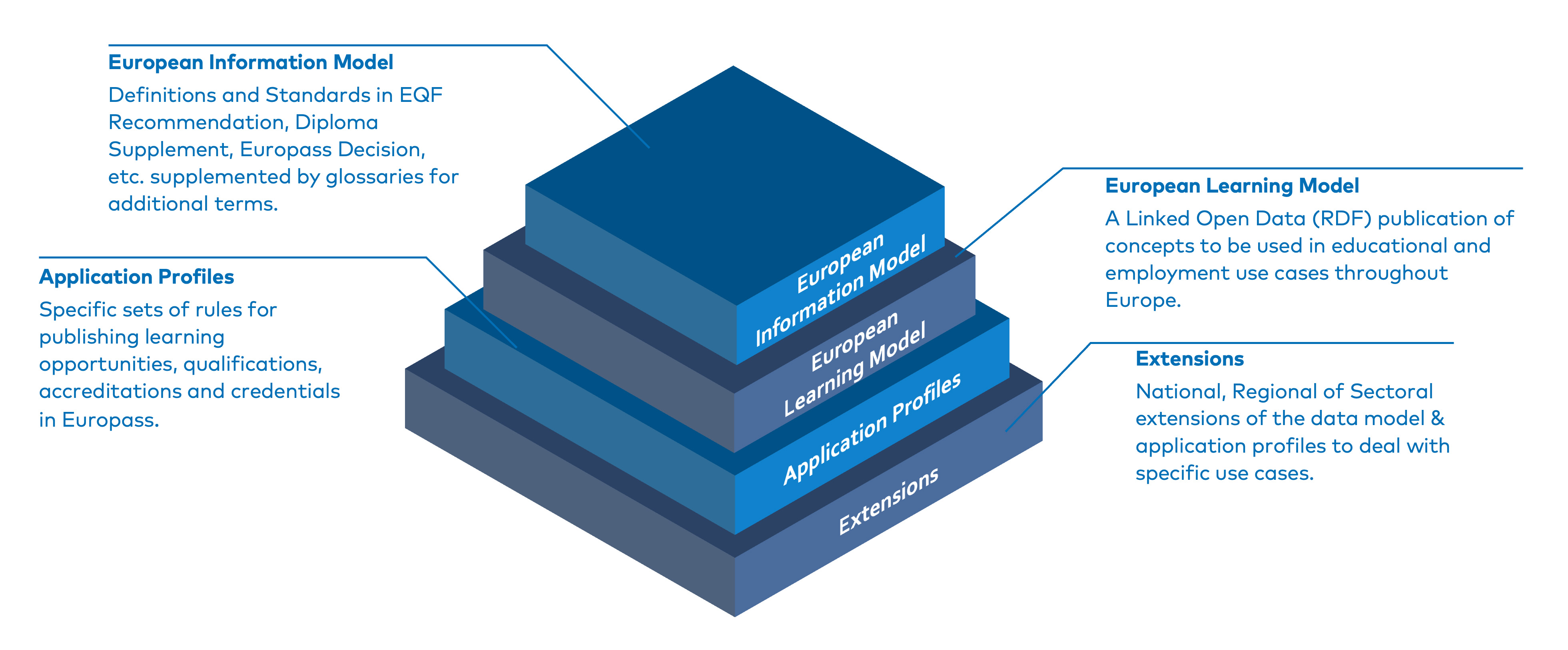

The European Learning Model (ELM)

The latest version ELM v3, launched in 2023, is targeted for all education and employment stakeholders in Europe. The ELM data model is built on open standards, the W3C Verifiable Credentials Data Model, and aligned with other models, including being fully compatible with ELMO and the EBSI Diploma Use Case. It is also linked to existing frameworks and classifications, for example EQF and ESCO.

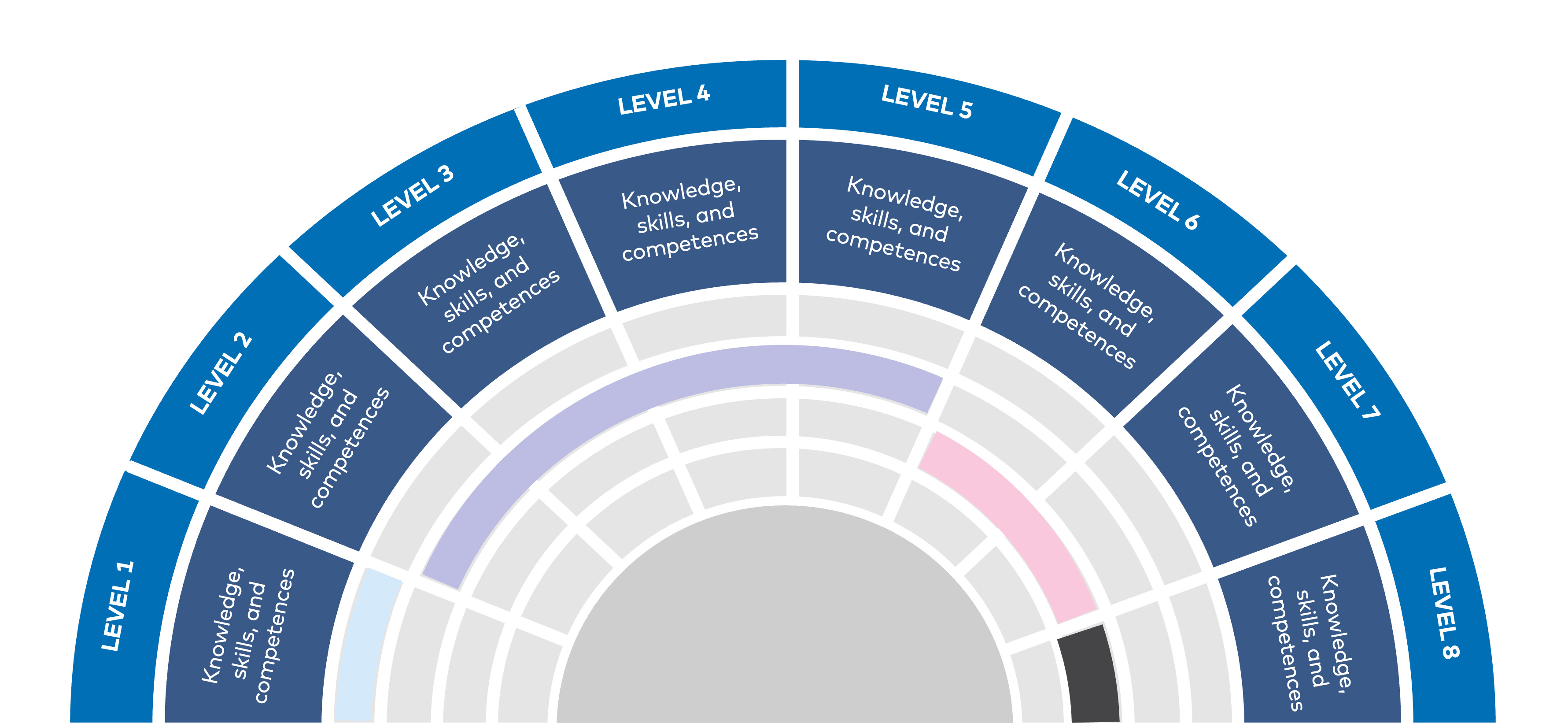

Figure 9. Four levels of ELM.

Picture adapted from https://europa.eu/europass/en/news/upcoming-launch-european-learning-model-v3. Cited 26.7.2023.

Picture adapted from https://europa.eu/europass/en/news/upcoming-launch-european-learning-model-v3. Cited 26.7.2023.

ELMO XML is a data format for the exchange of mainly educational credential information. It is based on the CEN standard EN 15981–2011 EuroLMAI. EuroLMAI is a data model describing assessments, primarily diplomas, diploma supplements, and transcripts of records for higher education. Elmo XML is an open-source data format, and the latest official version is available at EMREX GitHub repository.

EMREX

The initial goal of EMREX was to make student mobility processes easier. The student was placed in the driver’s seat of their own digitised educational credentials, allowing the student to decide which information to share digitally with whom. This MyData principle has given also new possibilities to utilise EMREX. For example, Norwegian employers use EMREX to receive applicants’ educational credentials into their recruitment systems. In Finland, EMREX has been used as an educational credential transmitting tool between education providers within Finland.

See chapter 3.4 Experiences from real-life environments

All development that will be done has to concentrate on systems and standards. They must be clear, set on common standards, and further interoperability. Constant introduction of new instruments might be less beneficial than developing interoperability of existing systems.

The Erasmus Without Paper (EWP)

Both EMREX and EWP are platforms for the electronic exchange of data for higher education institutions. Both may be used to transfer transcripts of records, diploma supplements, and course catalogues in different user scenarios: EWP supports education institutes’ administrative staff and administrative processes, while EMREX provides a set of electronic services to students.

DC4EU

The aim of the Single Digital Gateway (SDG)

Once Only Technical System (OOTS)

The SDGR regulatory procedures in Annex II focus on three life events/procedures concerning educational data that should be accessible across the EU by using OOTS.

Title of the procedure in Annex II | Expected output |

#3 Applying for tertiary education study financing, such as study grants and loans from a public body or institution | Decision on the application for financing or acknowledgement of receipt |

#4 Submitting an initial application for admission to public tertiary education institution | Confirmation of the receipt of application |

#5 Requesting academic recognition of diplomas, certificates or other proof of studies or courses | Decision on the request for recognition |

As a concrete step towards OOTS, for example, the Nordic Council of Ministers has launched the SDG OOTS Proof-of-Concept (PoC) pilot project

ESCO

The Europass Digital Credentials Infrastructure (EDCI) is being developed by the European Commission. The idea is that organisations will be able to implement the issuance of digital credentials for free. This supports the shift from paper-based certificates to digitally signed credentials. The EDCI data model, ELM, is aligned with the ELMO XML standard.

The European Qualifications Framework (EQF)

I can see that digital credentials are here to stay; we see the value for all in these. Also, keep the student in mind, more than anything else when developing cross-border data exchange within the study sector.

Figure 10. EQF framework in nutshell

3.3 Networks and stakeholders

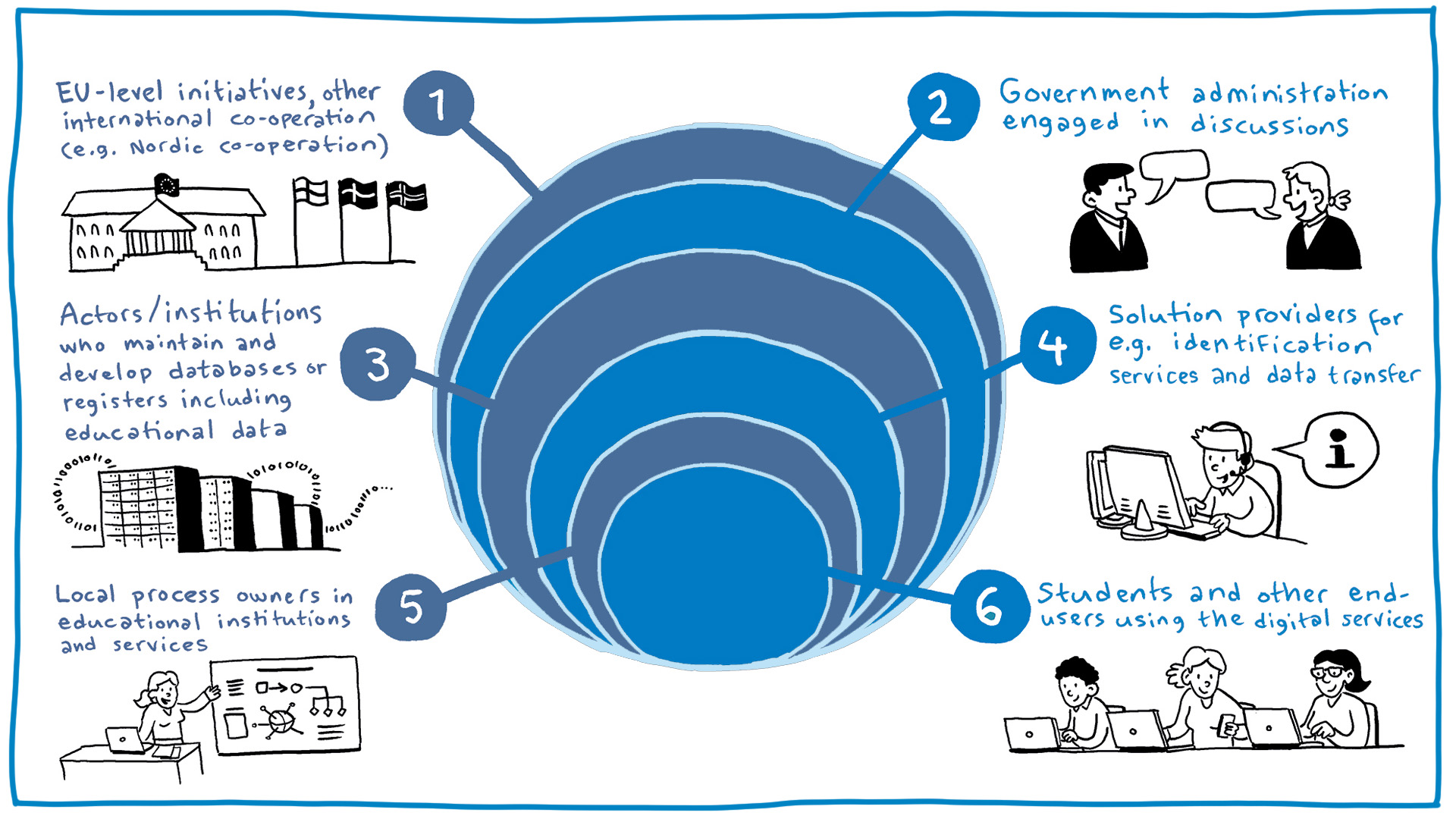

Cooperation with other relevant projects, stakeholders and networks is an essential success factor in projects related to cross-border data exchange. Numerous projects and plans to improve digital services for students are ongoing or previously implemented at the national, Nordic, and Baltic countries, and EU level. The challenge is, who should you turn to when you have development ideas, requests for cooperation or further questions? When developing cross-border digital services we recommend engaging and following stakeholders on these different levels.

Figure 11. Levels of stakeholder engagement in cross-border data exchange projects

To begin with, it is essential to find the right people from each country in scope who possess deep knowledge of the practices, processes, key responsible parties in the country as well as the country-specific challenges, strengths, concerns, and other viewpoints to the project execution and outcomes.

- Monitor EU-level initiatives, other international cooperation (e.g. Nordic Co-operation). To identify possible interdependencies and get an overall picture of the context in question, we recommend that you familiarise yourself with this policy-level view.

- Keep government administration engaged in discussions, as the ministries are responsible for policy level decision-making including resources and national steering also in the field of education and digitalisation.

- Cooperate with actors/institutions who maintain and develop databases including educational data across borders. This level includes governmental agencies responsible for education and digitalisation under the ministerial level, for example. In many countries, there are also joint and centralised IT/data service providers for higher education institutions. For example, CSC in Finland, Sikt in Norway and established in 2023, VPC (Higher Education and Science Information Technology Shared Service Center) created by four universities in Latvia.

- Work with solution providers. For example, in the development of digital services, identification and data transfer solutions play a role in the processes and use cases. To find relevant stakeholders and to establish close relationships with these actors, is important and sometimes a critical factor for a project’s success.

- Coordinate well with local process owners in educational institutions and services. The benefits of the smooth cross-border data exchange of educational credentials are realised mostly in this level in the local processes.

- Engage students and other end-users in the digital service development. At its best, engagement begins from the very start of development work: users should be included in the planning of the new functionality or system and the related processes. When properly implemented, engagement is also an excellent method to allocate scarce resources based on needs.

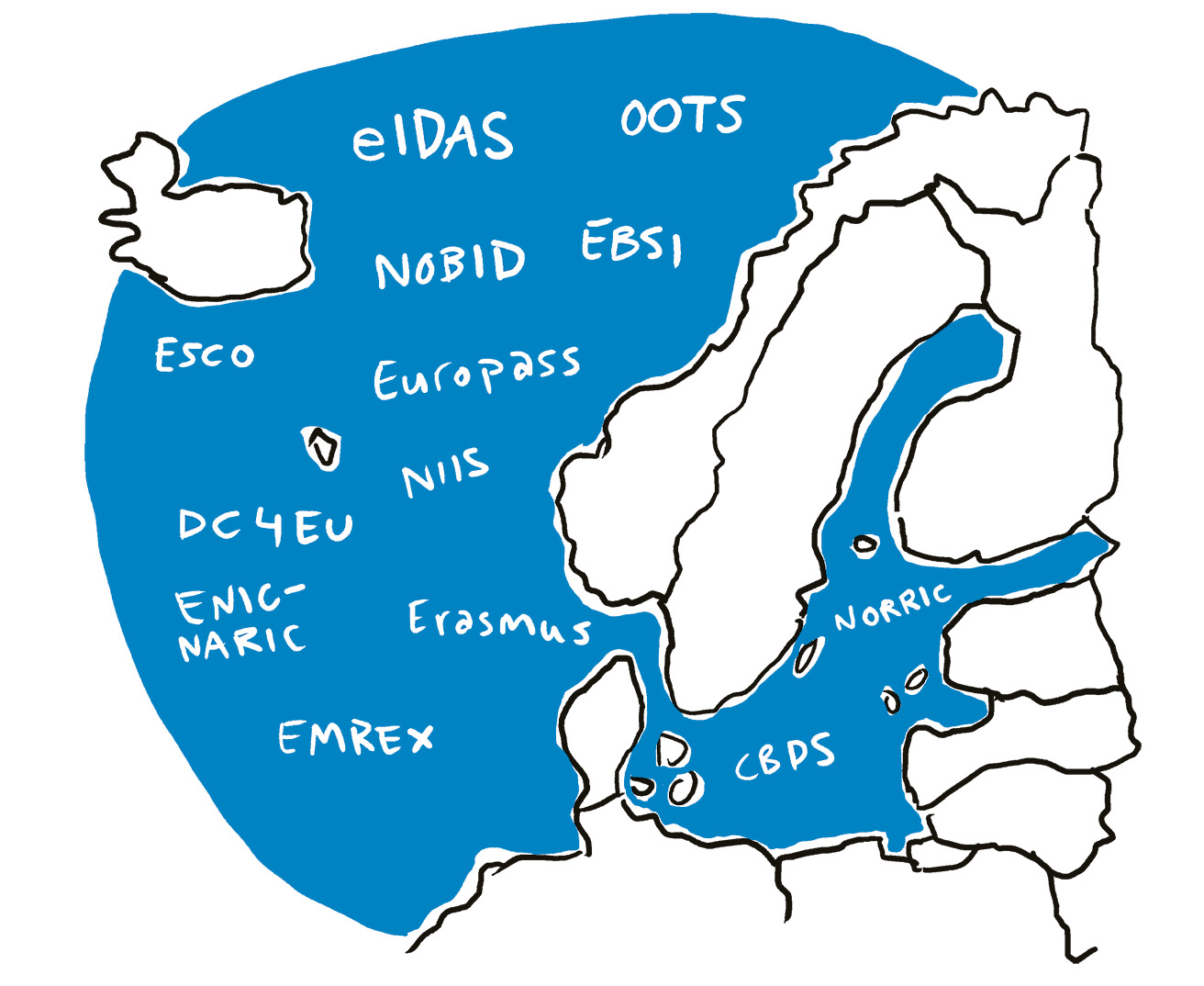

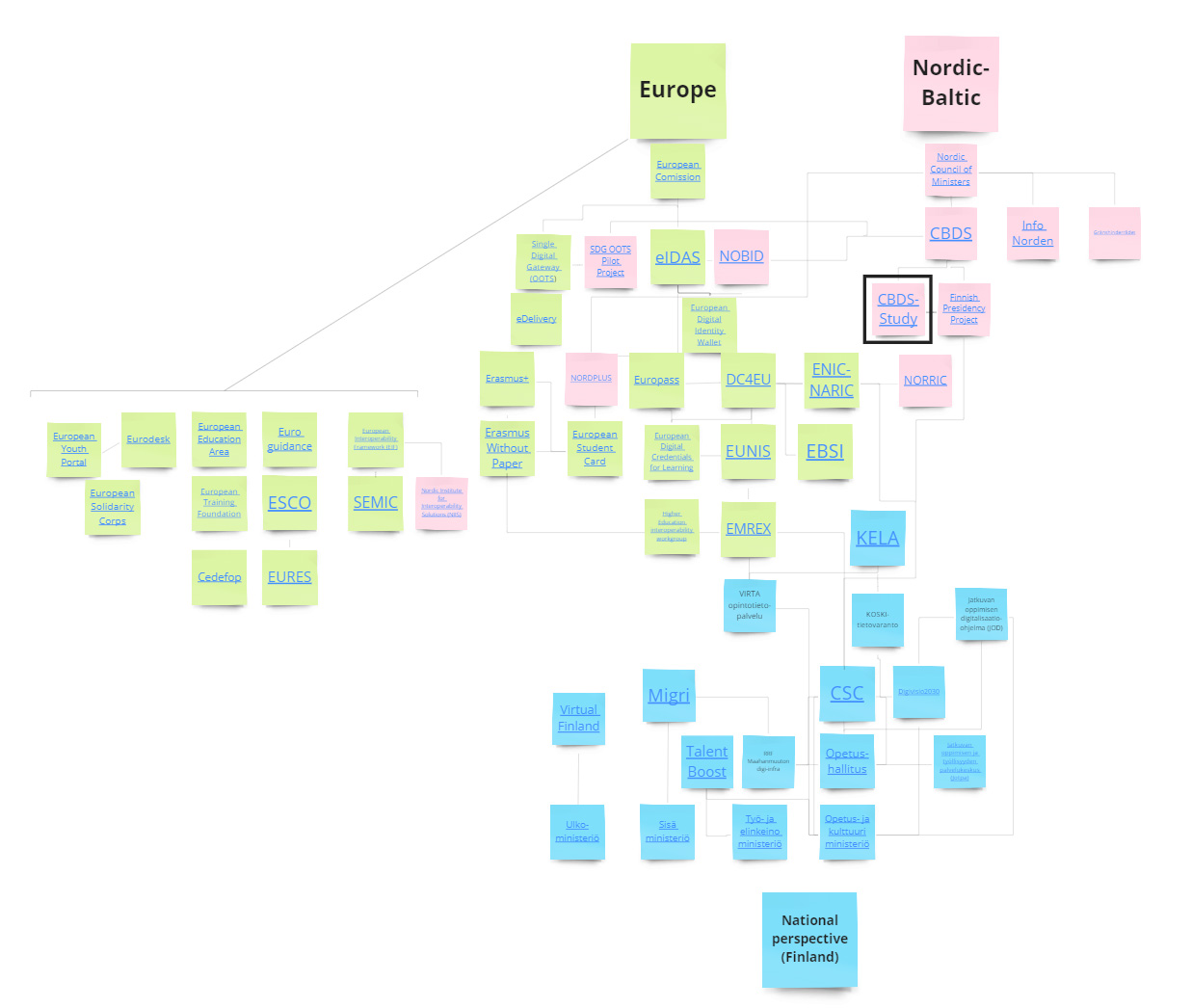

Example of a network and stakeholder map

In Figure 12, there is an example of a network and stakeholder map that was constructed in WP1 Studying in another Nordic-Baltic country by using a Miro board. It is one way to make visible the central actors, standards, and initiatives in the field of cross-border data exchange of educational data. The actors are divided and color-coded into three different categories: European, Nordic-Baltic, and national level. In this case, the national perspective is Finnish. There are also lines that mark the connections between the different actors and post-it notes contain a hyperlink to each actor’s webpage.

In Figure 12, there is an example of a network and stakeholder map that was constructed in WP1 Studying in another Nordic-Baltic country by using a Miro board. It is one way to make visible the central actors, standards, and initiatives in the field of cross-border data exchange of educational data. The actors are divided and color-coded into three different categories: European, Nordic-Baltic, and national level. In this case, the national perspective is Finnish. There are also lines that mark the connections between the different actors and post-it notes contain a hyperlink to each actor’s webpage.

Figure 12. An example of WP1’s network and stakeholder map in the context of cross-border data exchange of educational data 2021−2023

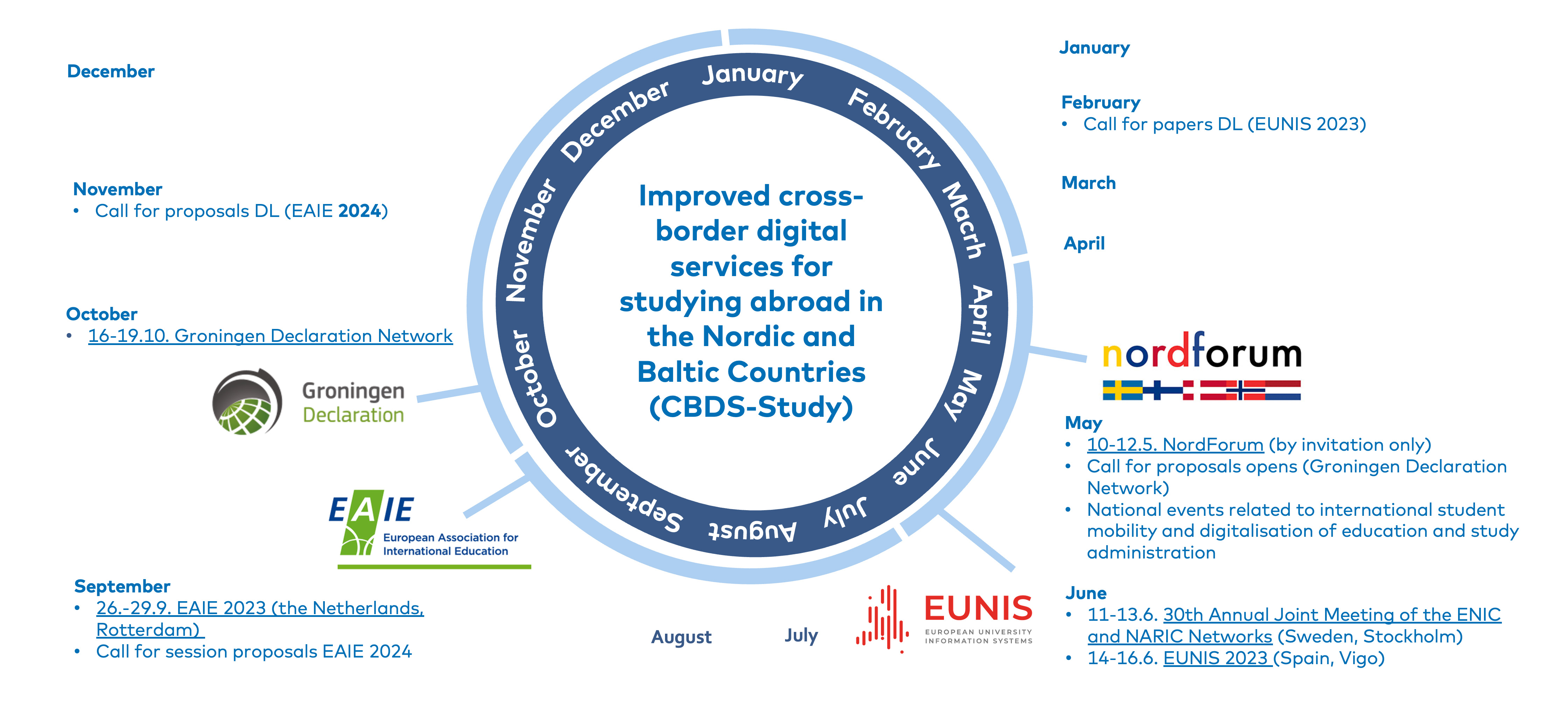

Example of a network and events annual clock

The events organised by the networks in the context of the project are the best arenas for connecting people and other projects, gaining new perspectives, changing good practices, and disseminating project results. For the Nordic-Baltic data exchange of educational data projects, the relevant networks, and their events to follow might be such as EUNIS

The events organised by the networks in the context of the project are the best arenas for connecting people and other projects, gaining new perspectives, changing good practices, and disseminating project results. For the Nordic-Baltic data exchange of educational data projects, the relevant networks, and their events to follow might be such as EUNIS

Figure 13. An example of a networks and events annual clock

3.4 Case examples of the exchange of educational credentials and interoperability in practice

In this chapter, we would like to introduce three case examples of interoperability in exchanging educational credentials. Two examples are related to EMREX − a technical solution for transferring verified educational credentials electronically mentioned earlier in chapter 3.2. The third case describes the use of an EBSI blockchain in practice.

Case EMREX & Finnish Metropolia University of Applied Sciences

Metropolia University of Applied Sciences in Finland has, amongst the first Finnish higher education institutions, introduced an electronic service based on EMREX.

For the student, the new service makes the educational credential transfer process much easier. Earlier, the educational credential transfer process has heavily relied on paper documents and their manual processing and verification. This leads to human error and requests for supplementary and additional information occur quite often. EXREX enables the cross-border exchange of educational credential information in a machine-readable format and reduces the administrative burden for the process. It also substantially increases the reliability of the data as it is hard to destroy or change it in any way during the transfer process.

The solution can be used between higher education institutions between different countries as well as within one country.

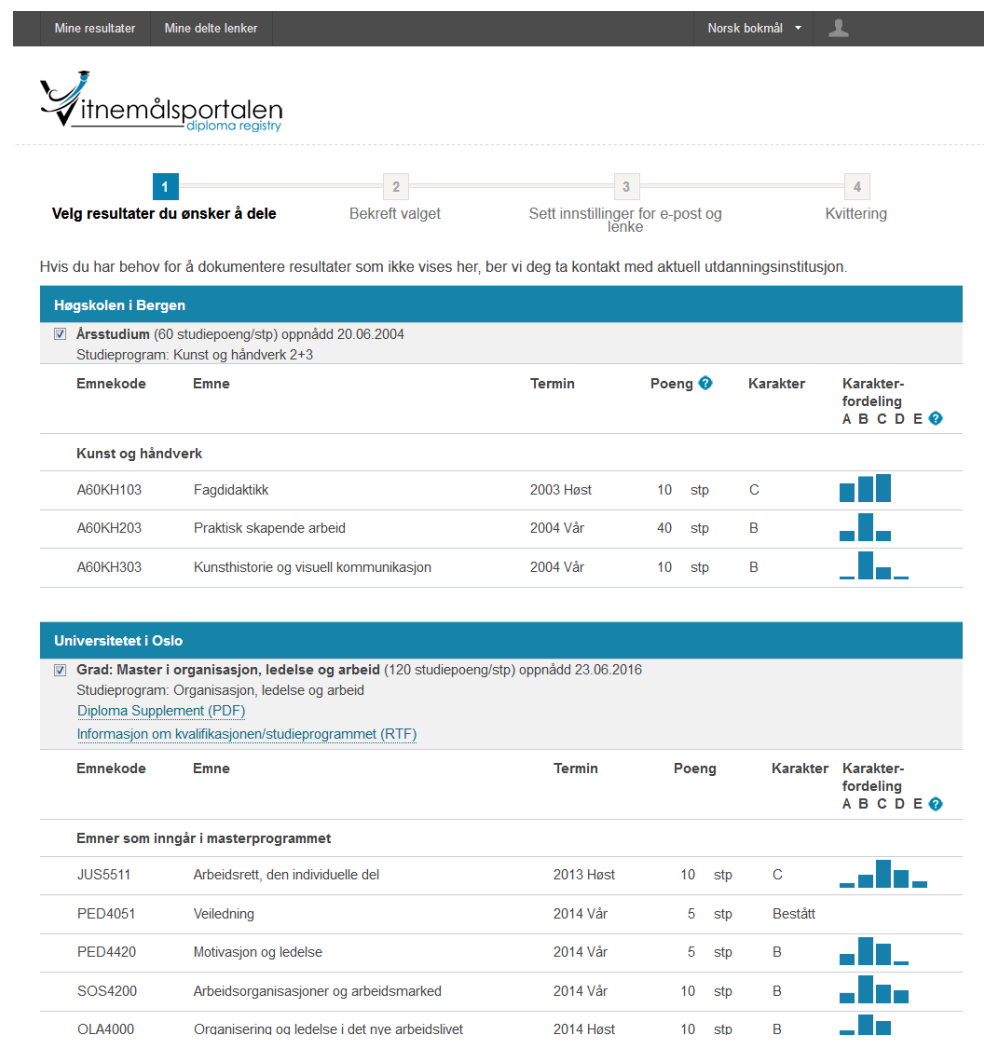

Case EMREX & Norwegian Diploma Registry

Norway is a forerunner in utilising EMREX. The Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research’s commissioned Norwegian Diploma Registry

The amount of EMREX sharing has multiplied in last couple of years, since growing number of recruitment services are connected to the Diploma Registry using the EMREX protocol. Additionally, the production of paper versions of transcripts of records has been reduced to a minimum.

At the beginning of 2023, the Norwegian Diploma Registry was already in use for example in recruitment systems, education admission systems, licenses, and authorisation applications. Norwegians already have plans to expand the scope and utilise EMREX also for other kinds of education, knowledge, and skills, such as vocational education, professional certificates, language tests, driver’s licenses and more.

Figure 14. Vitnemålsportalen https://www.vitnemalsportalen.no

Case EBSI – MicroBlock in Tampere University and DLTnode in Kaunas University of Technology

The University of Tampere has engaged itself in a two-year EBSI blockchain research project, led by the European Commission, which is being co-developed between different type of institutions around Europe. By connecting to the EBSI-blockchain infrastructure, European higher education institutions enable the sharing of cross-border education credentials, both European Student Identifiers and Micro-Credentials.

The project is running simultaneously with a project that is taking place in Kaunas University of Technology in Lithuania. The objective of the EBSI blockchain research project is to standardise the use of EDCL-based digital credentials and their data, such as developed competences. The standardisation focuses on the exchange and recognition of the credentials. It also ensures the simplicity and reliability of the cross-border issuance and verification of digital credentials. It also allows flexible study pathways for learners. In practice, student should be entitled to request an individual Academic ID and Micro-Credential from their home institution. Second, a student could apply for a course in another institution by sharing their individual Academic ID and Micro-Credential. Subsequently, after the Academic ID and Micro-Credential has been verified by the institution offering the desired course, the student is able to enrol on that course, and entry to that course can be granted. Consequently, the receiving institution may receive and share the Micro-Credential, allowing it to share it with the home university and transfer data, such as the progress, grades or other necessary information related to the study abroad.

3.5 Key take-aways

In chapter 3, we have introduced some European standards and frameworks of educational data and ways to engage with different stakeholders and networks. In addition, case examples related to the exchange of educational credentials and interoperability in practice have been presented.

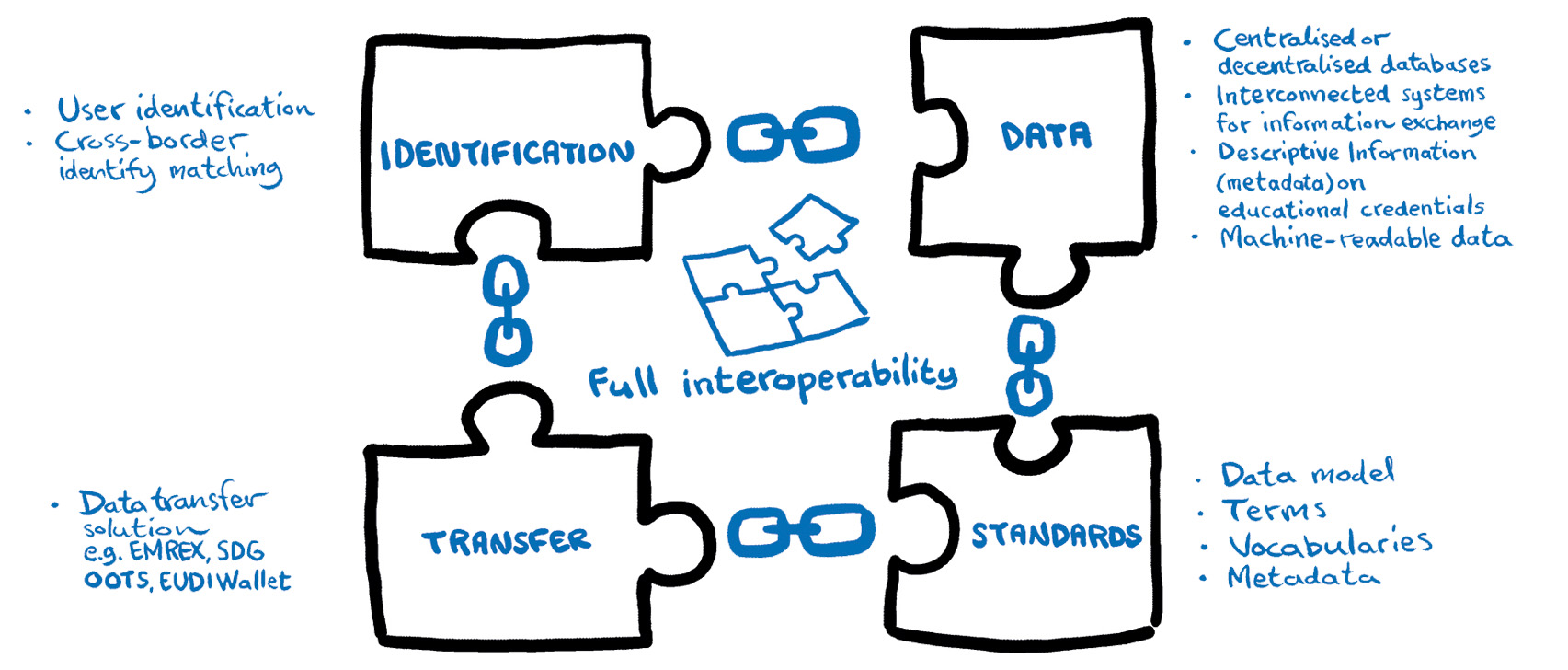

A ’cross-border by default’ principle, to which the Nordic and Baltic countries’ are committed to in all development of digital services was mentioned in the introduction of the handbook. Full interoperability in the study context could be described, for example, as a world in which the digital application for cross-border education would be easy, simple, and efficient both for the student and for the education institute. The student could seek education opportunities via information systems and portals hosted by the recipient country and digitally share information on his or her study background in the form of a transcript of records. The educational credentials would also include descriptive information about the contents of the completed studies and the information could be utilised in the student selection process.

As a key take-away, we would like to summarise the requirements for cross-border data exchange of educational credentials by describing the components that enable the smooth data exchange. The picture below tackles technical and semantic interoperability and it sets aside the soft infrastructure, practices at the educational institution level and legal issues. As long as the regulation and its interpretation along with local processes of the educational institutions vary significantly, the full potential of interoperability will not be achieved.

Figure 15. Requirements for cross-border data exchange of educational credentials. Components that enable the smooth data exchange.

In addition, these three aspects cannot be overemphasised when developing interoperable cross-border data exchange of educational credentials:

To understand the big picture of standards and frameworks is essential.

Active collaboration with stakeholders and relevant networks is the key to success.

Already functioning interoperable solutions and practices should be taken into account.

To understand the big picture of standards and frameworks is essential.

Active collaboration with stakeholders and relevant networks is the key to success.

Already functioning interoperable solutions and practices should be taken into account.

1. The big picture of standards and frameworks

It is highly recommended to get an overview of the connections between standards, data models and other related projects when starting or implementing a project in the field of cross-border exchange of educational data. Desktop research and documentation at the early stage will save time and prevent possible overlapping and double work and could help to point important collaboration instances.

It is highly recommended to get an overview of the connections between standards, data models and other related projects when starting or implementing a project in the field of cross-border exchange of educational data. Desktop research and documentation at the early stage will save time and prevent possible overlapping and double work and could help to point important collaboration instances.

2. Active collaboration with stakeholders and relevant networks

It is fundamental to find the right people, organisations, and networks from each country in scope. They possess the knowledge of the local practices and processes as well as the country-specific challenges and strengths. Events orga-ni-sed by the projects themselves and participation in more established forums, such as conferences and network meetings in the field have proven to be effective in promoting dialogue between actors. It is also crucial to find out who has the mandate to make the necessary decisions when needed.

It is fundamental to find the right people, organisations, and networks from each country in scope. They possess the knowledge of the local practices and processes as well as the country-specific challenges and strengths. Events orga-ni-sed by the projects themselves and participation in more established forums, such as conferences and network meetings in the field have proven to be effective in promoting dialogue between actors. It is also crucial to find out who has the mandate to make the necessary decisions when needed.

3. Already functioning interoperable solutions and practices

It is also useful to keep in mind the already functioning solutions that are aiming at interoperable ecosystems in the EU and beyond.

It is also useful to keep in mind the already functioning solutions that are aiming at interoperable ecosystems in the EU and beyond.

References

- European Commission. European Data Strategy. Available: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/european-data-strategy_en. Cited 18.7.2023.

- Fridell., T., Vangen, G., Mincer-Daszkiewicz, J., Norder, J.J., Kohtanen, J., Drvodelic, I., Bacharach, G. (2022). Interoperability of educational data demands standards. Available: https://www.eunis.org/download/2022/EUNIS_2022_paper_13.pdf. Cited 15.8.2023.

- See handbook Chapter 2.3 Potential funders

- European Union. (2023). Upcoming launch of the European Learning Model v3. Available: https://europa.eu/europass/en/news/upcoming-launch-european-learning-model-v3. Cited: 26.7.2023.

- ELM and QDR GitHub Repository. (2023). Available: GitHub - european-commission-empl/European-Learning-Model: Data Model for the Europass Digital Credentials Infrastructure. Cited 26.7.2023.

- EMREC GitHub Repository. (2023). Available: https://github.com/emrex-eu/elmo-schemas. Cited: 26.7.2023

- EMREX. (2023). Available: https://emrex.eu/. Cited 26.7.2023.

- See handbook chapter 3.4 Experiences from real-life environments

- European Commission. (2023). Erasmus Without Paper (EWP). Available: https://erasmus-plus.ec.europa.eu/european-student-card-initiative/ewp. Cited 27.7.2023.

- EWP Registry Services. (2023). Available: EWP Registry Service (erasmuswithoutpaper.eu). Cited 27.7.2023.

- Mincer-Daszkiewicz, J. (2017). EMREX and EWP offering complementary digital services in the higher education area. EUNIS 2017, Münster, Germany. Available: https://wiki.uni-foundation.eu/download/attachments/1149171/EUNIS_2017_paper_3%20%281%29.pdf?version=1&modificationDate=1598870027676&api=v2. Cited 27.7.2023.

- DC4EU. (2023). Available: https://www.dc4eu.eu/. Cited 26.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2022). The Single Digital Gateway and Your Europe. Available: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/single-market/single-digital-gateway_en. Cited 26.7.2023.

- Official Journal of the European Union. (2022). SDG Regulation EU2022/1463. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018R1724&from=EN. Cited 26.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). Once Only Technical System (OOTS). Available: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/wikis/display/DIGITAL/Once+Only+Technical+System. Cited 26.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2021). eID. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/wikis/display/DIGITAL/eID. Cited 26.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). eDelivery. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/wikis/display/DIGITAL/eDelivery. Cited 26.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). ESCO portal. Available: https://esco.ec.europa.eu/en. Cited 27.6.2023.

- European Commission. (2022). Europass. Available: https://esco.ec.europa.eu/en/about-esco/escopedia/escopedia/europass. Cited 29.8.2023.

- European Union. (2023). The European Qualifications Framework. Available: https://europa.eu/europass/en/europass-tools/european-qualifications-framework. Cited 27.7.2023.

- Nordic Council of Ministers. (2021). Baseline study of cross-border data exchange in the Nordic and Baltic countries. Work package 1 – Studying in another Nordic or Baltic country. Available: https://pub.norden.org/temanord2021-547/#88554. Cited 29.8.2023.

- EUNIS. (2023). EUNIS website. Available: https://www.eunis.org/. Cited 29.8.2023.

- European Association for International Education. (2023). EAIE website. Available: https://www.eaie.org/. Cited 29.8.2023.

- Groningen Declaration Network. (2022). Website. Available: https://groningendeclaration.org/. Cited 29.8.2023.

- CSC. (2022). NordForum. Available: https://www.csc.fi/-/nordforum. Cited 29.8.2023.

- Metropolia. (2023). Korkeakoulujen seuraava digiloikka: tiedot vaihto-opinnoista liikkuvat jatkossa sähköisesti yli maarajojen. Metropolia’s announcement on the utilization of EMREX (in Finnish). Available: https://www.metropolia.fi/fi/metropoliasta/ajankohtaista/uutiset/korkeakoulujen-seuraava-digiloikka-tiedot-vaihto-opinnoista-liikkuvat-jatkossa-sahkoisesti-yli-maarajojen. Cited 27.7.2023.

- DVV. (2023). Press release: Digital leap in the transfer of study credits: data on studies completed elsewhere can now be transferred electronically across borders. Available: https://dvv.fi/en/-/digital-leap-in-the-transfer-of-study-credits-data-on-studies-completed-elsewhere-can-now-be-transferred-electronically-across-borders. Cited 27.7.2023.

- Sikt – Vitnemålsportalen. (2023). Norwegian Diploma Registry. Available: https://www.vitnemalsportalen.no/english/. Cited 27.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). Micro-credentials. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/wikis/display/EBSI/Micro-credentials. Cited 29.8.2023.

- Strack, H., Gollnick, M., Karius, S., Bacharach, G., Fridell, T., Gottlieb, M., Norder, J.J., Pongratz, H., Radenbach, W., Schmidt, C., Stanic, M., Vangen, G.M., Wassmann, A., Wefel, S. (2023). EU Cross-border and OOTS for HEI/Edu Workflows and Infrastructures with Interoperability, Standards, and Security. Available: https://www.eunis.org/eunis2023/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2023/05/080-Digital-IDEU-public-services-54-Strack.pdf. Cited 29.8.2023.

- Fridell, T. (2023) EMREX in your wallet. EMREX User group Executive Committee. Available: https://www.eunis.org/eunis2023/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2023/05/051-EU-Student-Mobility-16-Fridell.pdf. Cited 29.8.2023.