2. The ballpark and the key players

Today, our society operates heavily on data and information, and the knowledge, operations, and services derived from them. Public organisations have a tremendous amount of data of and related to their citizens. The overall goal of cross-border data exchange within and between the Nordic and Baltic countries is to ease the everyday lives of Nordic-Baltic citizens.

Not only are citizens targets of data exchange, but citizens also play a central role in cross-border data exchange by allowing, or denying, their data to be shared to different stakeholders. The MyData principle

National authorities provide the actual conditions for data exchange where international cooperation ensures working towards mutual goals with common standards and frameworks. The fourth key players in this context are the professionals of different fields of expertise who need to understand the possibilities and restrictions regarding cross-border data exchange as well as know the standards and systems they can utilise and benefit from in their respective development activities.

Figure 2. Key players in cross-border data exchange

A smooth digital service infrastructure enabling cross-border data exchange in the Nordic-Baltic region supports the shared visions of an open labour market area and the Nordic-Baltic countries being the most integrated region by 2030. The common digital service infrastructure also supports the formation of a common Nordic voice in relation to relevant stakeholders, such as the European Union. The cooperation framework supported by initiatives such as the Interoperable Europe Act for public administrations across the EU helps to agree on and build secure digital solutions for cross-border data exchange. Within the European, Nordic, and Baltic cooperation networks, the countries share resources and ideas, such as open-source software, guidelines, checklists, frameworks, and IT tools. Utilising existing solutions reduces administrative burdens, including legal, organisational, semantic, and technical obstacles. As a result, it will save time and costs for companies and citizens, businesses, and for the public sector itself.

To be able to provide seamless public services with cross-border data, the interoperability of different national solutions will need to be addressed. Essentially, interoperability is about achieving common goals together, despite organisational or geographical distance between actors. Public sector interoperability represents the ability of administrations to cooperate and make public services function across borders, sectors, and organisational boundaries. It will save time, costs and efforts when simplifying the interactions with administration by using the data already collected by another administrative body whether in the same or another country. The key to success is the professionals in charge of the development, making sure cross-border collaboration aspects are a default setting in all development decisions.

Emphasising personal contacts and soft infrastructure is extremely important in developing the cross-border data exchange.

2.1 Standards and frameworks

The European Commission strongly promotes data-driven development, the ‘once only’ principle, and making Europe fit for the digital age. The Commission aims at strengthening Europe’s digital sovereignty and setting standards that have a clear focus on data, technology, and infrastructure. Not only is the EU’s digital strategy seen as empowerment for people and businesses, but also helping the EU to achieve its target of a climate-neutral Europe by 2050.

European regulation is implemented nationally. National authorities coordinate the implementation nationally and they involve needed national sectoral agencies into piloting and later implementing the legislation. Recognise the parties involved in your country! Contact persons can in most cases be found from national agencies’ webpages.

In this chapter are highlighted some central strategies, regulations, standards, and frameworks which the reader should at least be aware of. On a larger scale this proves the importance of digitalisation and the political will to achieve these goals at the national, Nordic-Baltic, and European level. In addition to these cross-domain frameworks, different domains such as health services, education and judicial have established domain-specific standards and frameworks.

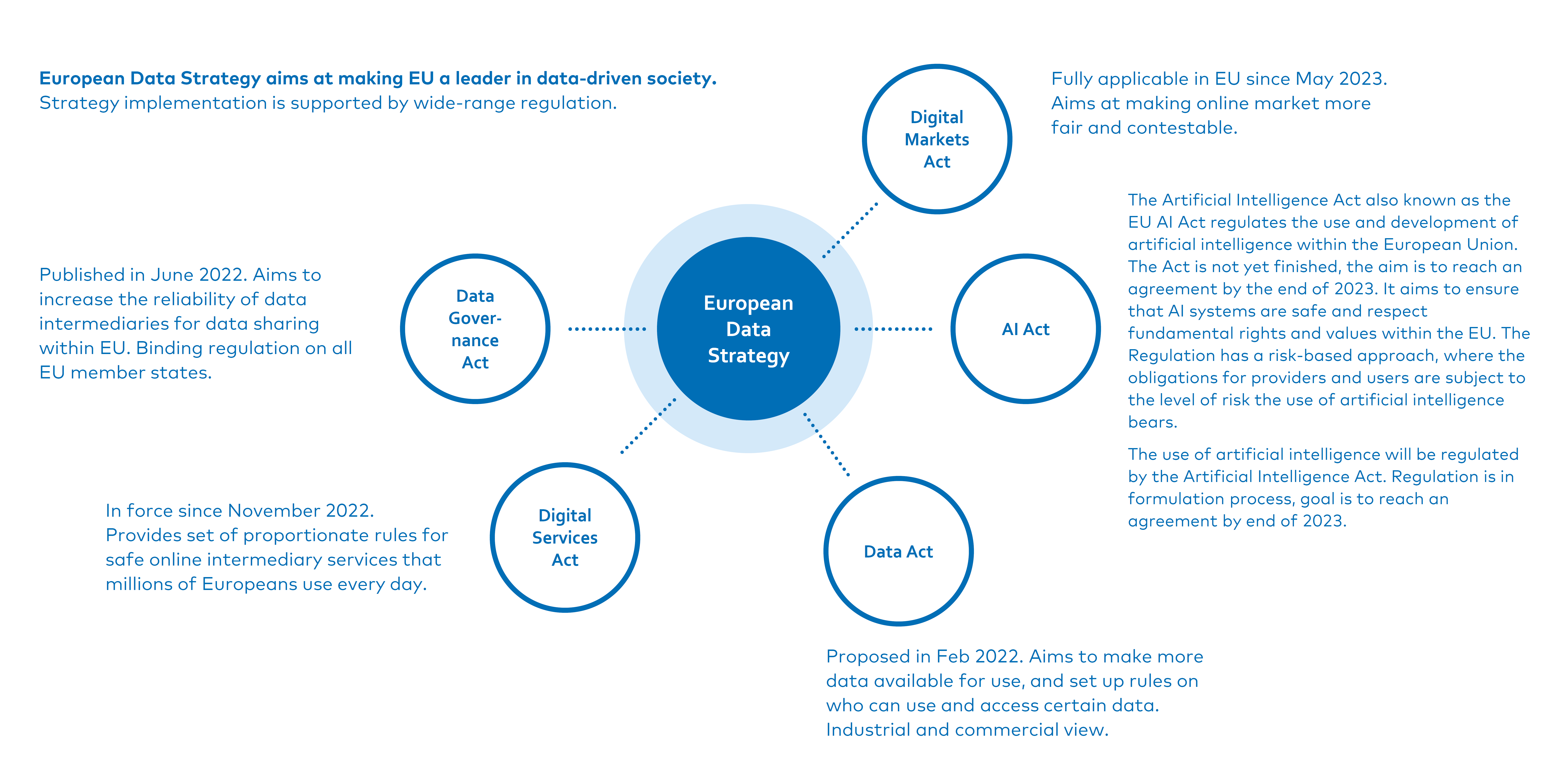

Figure 3. European Data Strategy and some key Acts supporting its implementation

The European Data Strategy

The Data Act

The Data Governance Act (DGA)

The Digital Services Act (DSA)

The Digital Markets Act (DMA)

For the public sector, the EU additionally provides both regulation and guidance to promote and facilitate cross-border interoperability and data sharing:

The Public Sector Information (PSI) Directive, or Open Data Directive

The Interoperable Europe Act

Case examples already implementing these above-mentioned regulations include a Finnish interoperability platform

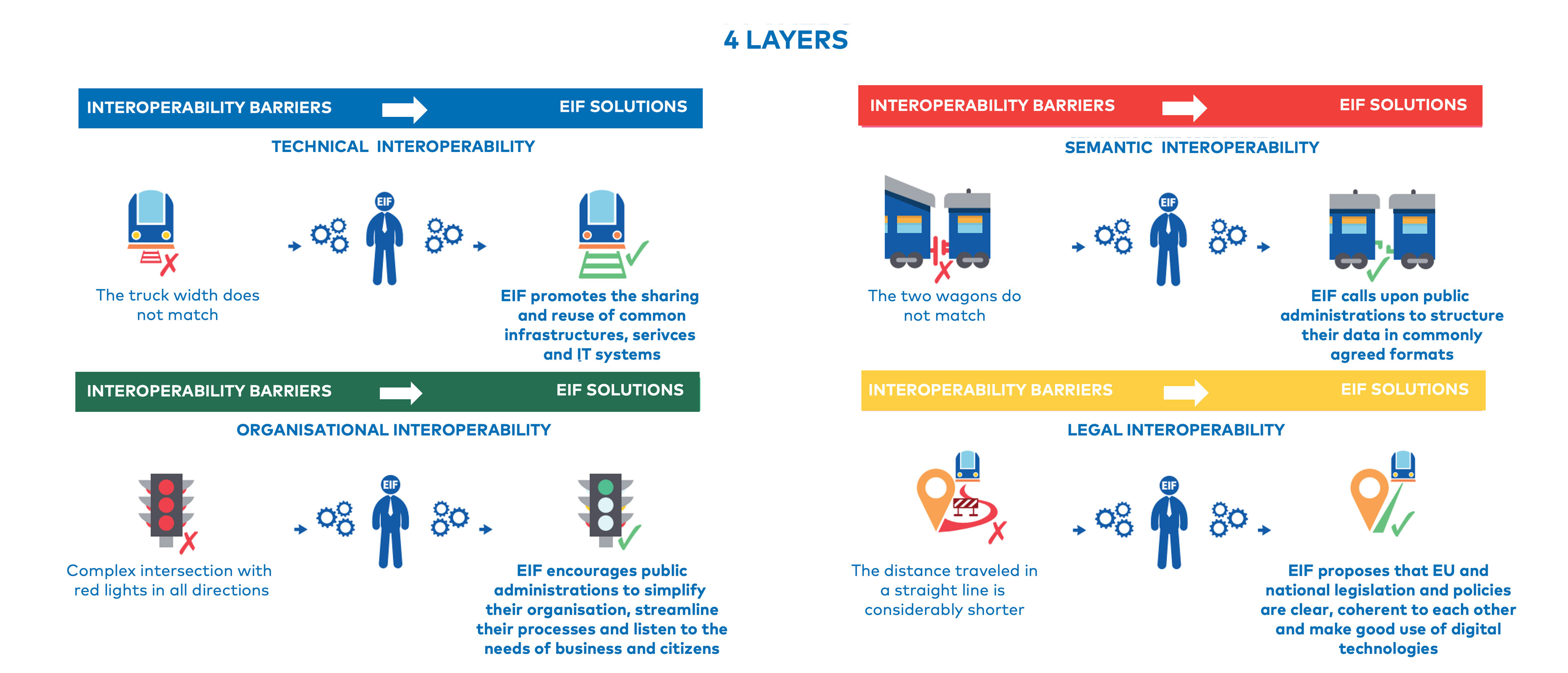

To facilitate and support cross-border development work, the European Interoperability Framework (EIF)

The European Interoperability Framework (EIF) analyses interoperability in four layers: legal, organisational, semantic, and technical interoperability.

- Legal interoperability confronts the different legal frameworks, policies, and strategies that may affect cross-border data exchange and collaboration.

- Organisational interoperability tackles the processes, structures, and responsibilities of public organisations that could impact mutually beneficial cross-border collaboration.

- Semantic interoperability ensures the format and meaning of exchanged data is preserved throughout the exchange process amongst all parties.

- Technical interoperability promotes the sharing and use of common infrastructures, services, and applications to make the digital cross-border data exchange possible.

The FI-Platform provides tools for defining interoperable data content. The platform consists of the terminologies, code sets and data models needed for data flows and in other areas of information management.

https://dvv.fi/en/interoperability-platform

gathers all Finnish open data on one free platform. An open license grants permission to use the data freely for any purposes – for administration, businesses, associations, or citizens. All data on opendata.fi portal is also harvested by European Data Portal.

https://www.opendata.fi/en

Figure 4. The New European Interoperability Framework. Source: https://ec.europa.eu/isa2/eif_en/ Cited: 18.7.2023.

EIF provides 47 recommendations, which are organised around three main pillars:

- 12 principles that guide policymakers in what to consider in the pursuit of interoperability

- Interoperability layers which present different aspects of interoperability that should be addressed in the design of European public services

- A conceptual model which aims at designing and delivering integrated public services.

The purpose of the EIF model is to inspire European public administrations in their efforts to design and deliver seamless European public services to other public administrations, citizens, and businesses to be digital-by-default (i.e., providing services and data preferably via digital channels), cross-border-by-default (i.e., accessible for all citizens in the EU) and open-by-default (i.e., enabling reuse, participation, and transparency). The Nordic-Baltic goal aims to achieve the exact same direction, with concrete Nordic-Baltic projects, experiments, and actual cross-border digital collaboration cases.

The European Blockchain Services Infrastructure (EBSI)

Figure 5. What is the EBSI?

Picture credit: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/wikis/display/EBSI/

Picture credit: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/wikis/display/EBSI/

The European Electronic Identification and Trust Services (eIDAS) Regulation

The EU Cybersecurity Strategy

The EU Cybersecurity Strategy

In June 2023, the European Parliament representatives reached a political agreement on the core elements of a new framework for a European Digital Identity (eID)

Wallets normally contain a variety of personal data concerning the wallet’s owner such as payment cards, identity cards, driving licences and various professional certificates. The EUDI Wallet application will contain the same authenticated personal data and certificates in an electronic form, and European citizens will be able to use the wallet application to access and share the needed data when using different kinds of services around Europe. EU Member states are expected to ensure there is at least one wallet application available to their citizens, but it will not be mandatory for citizens to use it.

During the project, some perspectives, services, and developments regularly came up as the cross-border data exchange and services were discussed. The most frequently arising matter was identity matching and acting on behalf of another person. The need to be able to identify an individual in different systems in different member states would improve the service for the individual, unburden the processes for the administration, and increase the quality of the service processes. In addition, practices involving acting on behalf of another person (e.g. on behalf of your child) vary significantly in member states as the development is planned and executed nationally. Additionally, in the future it will be important to develop interoperability for services and applications where it is possible to act on behalf of another person.

The Single Digital Gateway (SDG)

Technical preparations of the European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDI Wallet)

The European Commission has also provided funding through different funding elements (currently the Digital Europe project)

See chapter 2.3 Potential funding mechanisms

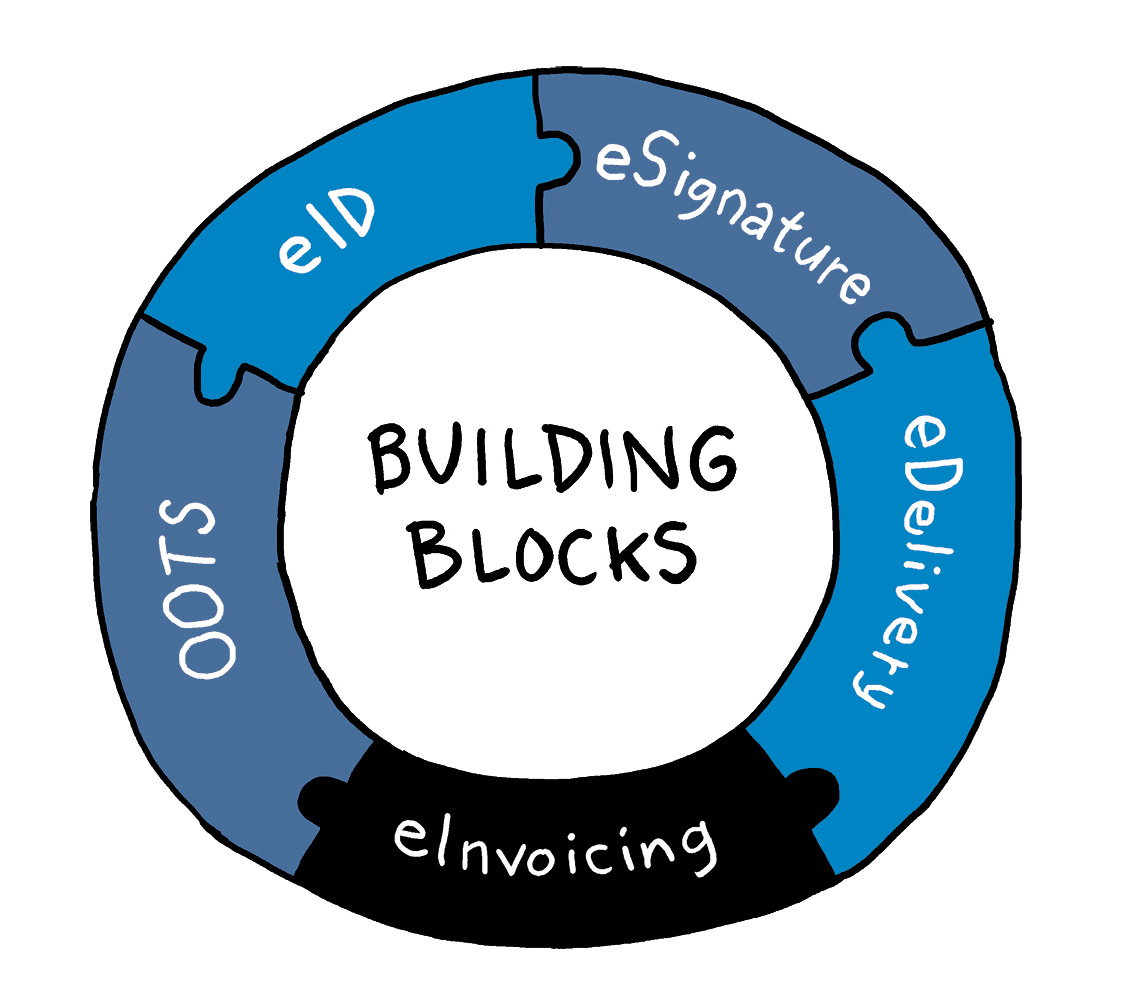

eID offers services capable of electronically identifying European users. eSignature helps create and verify paperless signatures, where eInvoicing helps send and receive invoices with automated processes, in line with EU standards. eDelivery provides tools for exchanging electronic data and documents securely.

Figure 6. Building Blocks for Digital Europe

The Once-Only Technical System (OOTS)

The goal of creating a Digital Europe requires a massive amount of collaboration both nationally and on a European level. There are several European working groups, communities, and projects focusing on building an interoperable Europe. For example, the European Commission’s SEMIC Support Centre

For example, DC4EU

The possibility to access digital services across borders in the Nordic-Baltic region is one of the main goals of the digitalization cooperation under the Nordic Council of Ministers. Cross-border service provisioning is a key enabler for cross-border mobility. The respective authorities responsible for means of electronic identity (eID) in the countries in the region, are working to achieve this under the Nordic-Baltic eID Project (NOBID).

A vital step to achieve this smoothly and safely is to identity matching. For service providers in the region to cater to users with a foreign eID from the region, they need to be able to recognize the user. This is especially important if the user has been in the country the service is provided in before and already has a form of identity registered. The duty of the identity matching solution is then to match the identity of the user provided by his or her home eID with the new or existing identity records of the same person in the country the person is seeking a service in.

An identity matching solution must be developed nationally in each country but coordinated and synchronized under the Nordic-Baltic cooperation on digitalization. There are many ways an identity matching solution could look, and many parts of the user journey the matching may take place.

An identity matching solution must be developed nationally in each country but coordinated and synchronized under the Nordic-Baltic cooperation on digitalization. There are many ways an identity matching solution could look, and many parts of the user journey the matching may take place.

OOTS eases citizens’ and businesses’ cross-border administrative duties. As an example, individuals can make declarations and requests to administrative bodies of receiving state prior to their physical moving to that Member State. The key objective of OOTS is to further mobility within the Union. In this context, scope of SDG regulation will expand, and it will be the central source of information exchange.

At the time of writing, the NOBID project is working on establishing best practice recommendations for the region and is also working on a roadmap on how identity matching could be achieved throughout the Nordic and Baltic countries. Recently, the Nordic and Baltic ministers responsible for digitalization have adopted a Ministerial Declaration that demonstrates a clear commitment to work towards an identity matching solution for the region.

The Ministerial Declaration provides important political leverage to the work conducted on an expert level. The declaration also stresses some of the key advantages the Nordic and Baltic region has, such as the maturity and similarity of the digital infrastructures, eID means and identity management processes, as well as the high level of trust and willingness among the countries in the region. These elements put the Nordic-Baltic countries in the best position to achieve identity matching across borders.

The CBDS Programme

A comprehensive list of digitalisation stakeholders in Europe, i.e. a list of EU Member States’ eIDAS implementation responsible organisations, and points of single contact can be found via the eID User Community.

In addition, in 2017 the Nordic and Baltic countries already formed a ministry level collaboration forum for digitalisation called MR-DIGITAL, which has the goal of enhancing overall digitalisation, as well as cross-border collaboration and integration in the Nordic and Baltic countries.

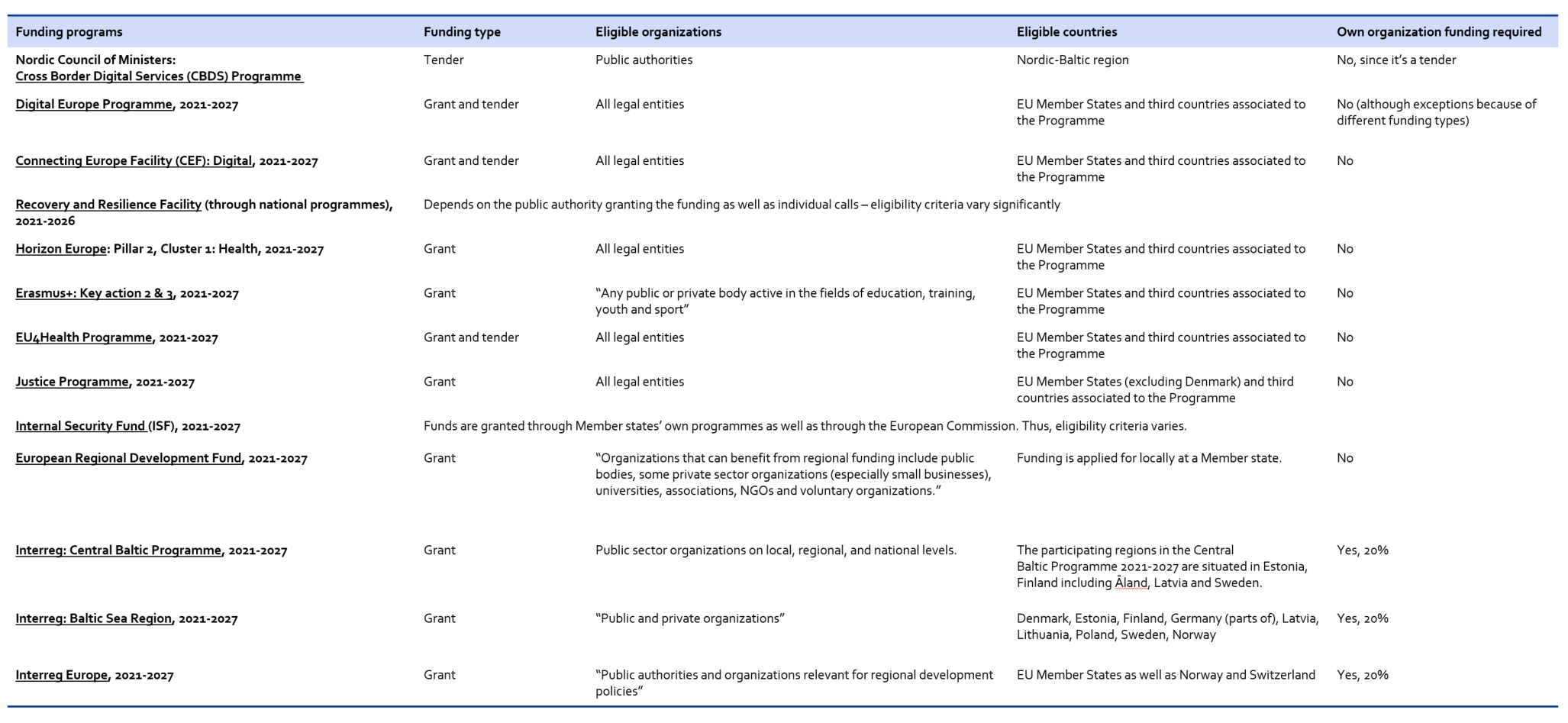

2.2 Potential funding mechanisms

When the need for interoperable services and the relevant parties are recognised, where can one find funding for development activities?

Funding is available through several channels with varying timetables and prerequisites. Information on funding can be found from the funders’ work programmes and websites. It is also good to keep an eye on policy papers as they may establish new funding programmes. Additionally, discussions with sectoral experts may reveal new or unharnessed funding possibilities.

Next, some potential funding mechanisms studied during the projects are highlighted.

The European Commission’s Digital Europe Programme

The DIGITAL Europe programme provides funding in five key areas: supercomputing, artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, advanced digital skills, and ensuring a wide use of digital technologies across the economy and society. The programme has several calls for funding. The calls will be published online, and the application is done through Commission’s Funding & tender opportunities portal.

Earlier, the Connecting Europe Facility programme (CEF Digital) (2014–2020) supported the adoption and reuse of digital building blocks in public and private projects and services on a continental scale. Now, the CEF Digital 2021–2027 programme aims to support and catalyse investments of common interest in the digital connectivity infrastructure.

The Nordic Council of Minister’s CBDS Programme also has an open funding mechanism to support the realisation of cross-border mobility in the Nordic-Baltic region by launching cross-sectoral projects. These projects are formed through specific calls for tenders.

Other potential funding mechanisms include the Recovery and Resilience Facility (2021–2026), European Regional Development Fund (2021–2027), Interreg: Central Baltic Programme (2021–2027), Interreg: Baltic Sea Region (2021–2027), and Interreg Europe (2021–2027).

Potential funding can also be found sector-specifically, for example for the educational sector there is the Erasmus+ Key action 2 & 3 (2021–2027) programme, while for the healthcare sector potential funding mechanisms include the Horizon Europe Pillar 2, Cluster 1 Health (2021–2027) and EU4Health Programme (2021–2027), and for legal interoperability there are funding programmes such as the Justice Programme (2021–2027) and Internal Security fund ISF (2021–2027).

Figure 7. List of potential funders for interoperable digital services development, Lauri Keskinen.

Source: https://wiki.dvv.fi/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=117377490&preview=/117377490/213629520/Overview%20on%20potential%20funding_CBDS%20Data%20exchange_DVV.pdf.

Source: https://wiki.dvv.fi/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=117377490&preview=/117377490/213629520/Overview%20on%20potential%20funding_CBDS%20Data%20exchange_DVV.pdf.

2.3 Artificial Intelligence (AI) in public cross-border services

As the use of artificial intelligence (AI) continues to advance and artificial intelligence evolves, this phenomenon will have an effect on the Nordic and Baltic societies. AI is expected to play an increasingly prominent role in the use and provision of services and decision-making, respectively. Currently, AI is not a major theme in cross-border data exchange processes. Nevertheless, it is a topic to follow on a regular basis, as it may prove to become a specific point of interest to authority organisations and civil servants working with cross-border data exchange. The availability of digital public services is expected to develop and become more easily accessible to users across borders. Nevertheless, before AI can be utilised in any cross-border applications, the quality and completeness of the data, as well as its interface and semantics must be well defined. Cross-border data exchange aims to answer the needs of citizens, and to provide services which they require in their daily activities taking place across borders.

The development of AI is expected to have at least some impact on the way services are provided and used. The efficiency and accuracy of AI-driven, automated, or semi-automated decision making is expected to reduce errors and the time of the processes involved. Citizens could benefit from AI-driven services or decisions that are efficient, personalised, and responsive to their needs. Regardless of the processes of the public administration counterpart, the citizen may also choose to utilise an AI-based external service in formulating or generating their requests for services. Automated decisions could scale to handle large volumes of transactions, promoting consistent and equitable outcomes. AI’s ability to analyse complex data patterns could help to uncover insights that inform better decisions and policies.

On the other hand, AI systems can inherit biases from the data used in their training, leading to unfair outcomes, thus affecting the citizens’ trust and rights. Due to the nature of AI, the complexity of algorithms may also lead to unintended consequences. The lack of transparency in processes utilising AI can erode trust and it may prove difficult to explicitly follow how data belonging to a specific individual is being used within the process.

From the point of view of public administration, artificial intelligence technologies are tools and instruments. Artificial intelligence, or any other technology, does not call into question existing regulations, principles of good governance or civil servant ethics. Regardless of whether the authority organisation uses artificial intelligence or not, the authority is responsible for the systems it uses and their proper utilisation. Official activity must be impartial, objective, and appropriate, whether it is implemented with artificial intelligence or not. Artificial intelligence is not an independent actor comparable to a human, but a complex and learning support technology.

Within the Nordic and Baltic countries, the current national regulations set boundary conditions for the use of algorithms in the production of services and decision-making.

References

- Ministry of Transport and Communications. Poikola, A., Kuikkaniemi, K., Honko H. (2015). MyData – A Nordic Model for human-centered personal data management and processing. Available: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-243-455-5. Cited 21.8.2023.

- European Commission. European Data Strategy. Available: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/european-data-strategy_en. Cited 18.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). Data Act: Commission welcomes political agreement on rules for a fair and innovative data economy. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_23_3491. Cited 18.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2022). European Data Governance Act. Available: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/data-governance-act. Cited 18.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2022). The Digital Services Act. Available: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/digital-services-act-ensuring-safe-and-accountable-online-environment_en. Cited 18.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). The Digital Markets Act. Available: Digital Markets Act: https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/index_en. Cited 20.7.2023

- European Commission. (2023). Open Data Directive. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/open-data-and-the-reuse-of-public-sector-information.html. Cited 20.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2022). Interoperable Europe Act. Available: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/interoperable-europe-act-proposal_en. Cited 20.7.2023.

- Finnish Digital and Population Data Services Agency. (2023). Interoperability platform. Available: https://dvv.fi/en/interoperability-platform. Cited 20.7.2023.

- Finnish open data repository. (2023). Available: https://www.opendata.fi/en. Cited 20.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). ISA2 – Interoperability solutions for public administrations, businesses, and citizens. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/isa2/eif_en. Cited 9.6.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). Introducing the EBSI. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/wikis/display/EBSI/Home. Cited 29.8.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). eIDAS Regulation. Available: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/eidas-regulation. Cited 29.8.2023.

- European Commission. (2022). The Cybersecurity Strategy. Available: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/cybersecurity-strategy. Cited 20.7.2023.

- European Council. (2023). Council and Parliament strike a deal on a European digital identity (eID). Available: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/06/29/council-and-parliament-strike-a-deal-on-a-european-digital-identity-eid/. Cited 29.8.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). Single Digital Gateway and Your Europe. Available: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/single-market/single-digital-gateway_en. Cited: 21.7.2023.

- Your Europe. (2023). Your Europe frontpage. Available: https://europa.eu/youreurope/index_en.htm. Cited 21.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). EU Digital Identity Wallet Pilot implementation. Available: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/eudi-wallet-implementation. Cited 20.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). eIDAS Expert Group. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/expert-groups-register/screen/expert-groups/consult?lang=en&groupID=3032. Cited 29.8.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). EUDI Wallet Toolbox. Available: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/eudi-wallet-toolbox. Cited 20.7.2023.

- Github. (2023). EUDI Wallet Toolbox materials. Available: https://github.com/eu-digital-identity-wallet. Cited 20.7.2023.

- See chapter 2.3 Potential funding mechanisms

- European Commission. (2023). The Building Blocks. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/wikis/display/DIGITAL/Digital+Homepage. Cited 20.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). Once Only Technical System (OOTS). https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/wikis/display/OOTS/OOTSHUB+Home. Cited 6.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). SEMIC Support Centre. Available: https://joinup.ec.europa.eu/collection/semic-support-centre. Cited 21.7.2023.

- DC4EU. (2023). Available: https://www.dc4eu.eu/. Cited: 21.7.2023.

- Digitaliseringsdirektoratet. (2023). The Nordic-Baltic eID Project (NOBID). Available: https://www.digdir.no/digdir/nordic-baltic-eid-project-nobid/1342. Cited 30.8.2023.

- NOBID Consortium. (2023). Available: https://www.nobidconsortium.com/. Cited 30.8.2023.

- Digitaliseringsdirektoratet. (2023). Cross Border Digital Services (CBDS) Programme. Available: https://www.digdir.no/internasjonalt-arbeid/cross-border-digital-services-cbds-programme/3058. Cited 26.7.2023.

- eID User Community. (2023). eIDAS Points of single contact. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/wikis/display/EIDCOMMUNITY/eIDAS+Points+of+single+contact. Cited 29.8.2023.

- Nordic Council of Ministers. (2023). Nordic-Baltic co-operation on digitalisation. Available: https://www.norden.org/en/information/nordic-baltic-co-operation-digitalisation. Cited 29.8.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). The Digital Europe Programme. Available: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/activities/digital-programme. Cited 18.7.2023.

- European Commission. (2023). Funding & tender opportunities. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/portal/screen/programmes/digital. Cited: 21.7.2023.

- Welcomeurope. (2023). CEF – Connecting Europe Facility – Digital – 2021-2027. Available: https://www.welcomeurope.com/en/programs/connecting-europe-facility/. Cited: 21.7.2023.

- Nordic Council of Ministers. (2023). Cross-Border Digital Services (CBDS) Programme. Available: https://www.digdir.no/internasjonalt-arbeid/cross-border-digital-services-cbds-programme/3058. Cited 21.7.2023.

- Sitra. (2022). Tekoälyn käyttömahdollisuudet julkisella sektorilla. Oikeudelliset reunaehdot ja kansainvälinen vertailu. (In Finnish). Available: https://www.sitra.fi/app/uploads/2022/03/tekoalyn-kayttomahdollisuudet-julkisella-sektorilla-sitran-selvityksia-206.pdf. Cited 29.8.2023.