PHOTOS: ISTOCK

4. Defining and measuring energy poverty

Section 4.1 gives a brief historical introduction to the concept of energy poverty followed by an overview of pivotal and current EU legislation and documents in sections 4.2 and 4.3, motivating the work on energy poverty in the Nordics as well as providing an EU wide definition. The EU definition sets the framework from which EU Member States are to define their own criteria and policy measures to address energy poverty. A description of the progress on defining energy poverty in each of the five Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) is examined in detail in section 4.4. Finally, a thorough discussion of the most prevalent and pertinent ways to measure the extent of energy poverty is provided in section 4.5, establishing a knowledge foundation for the further analysis.

4.1 Framework for understanding energy poverty

The original wording, fuel poverty, developed throughout the early 90’s and 00’s towards what is now called energy poverty in the EU. This change in terminology can be put down to a desire to avoid confusion, for whilst fuel poverty does include all energy services, the term can be interpreted as only relating to fuel input, for example, firewood or natural gas

Although it is hazardous to attribute a single author to the generation of a broad, overarching concept, the concept of fuel poverty was largely clarified and harmonised by the academic, Brenda Boardman, in the early 90’s, through her book, Fuel Poverty: From Cold Homes to Affordable Warmth

Identifying the group of households in energy poverty seems to be quite a difficult task. Having established the concept, Brenda argued for an indicator of fuel poverty defined as expenditure on fuel that is double the median expenditure on energy services, which at the time of her writing was 10 percent or more of income

It was not until another two years later, in 2003, following the wide-sweeping energy market liberalization that had occurred some six years earlier that the EU initiated their work on consumer protection. The concept of energy poverty appeared in EU legislation for the first time in the Third Energy Package in 2009

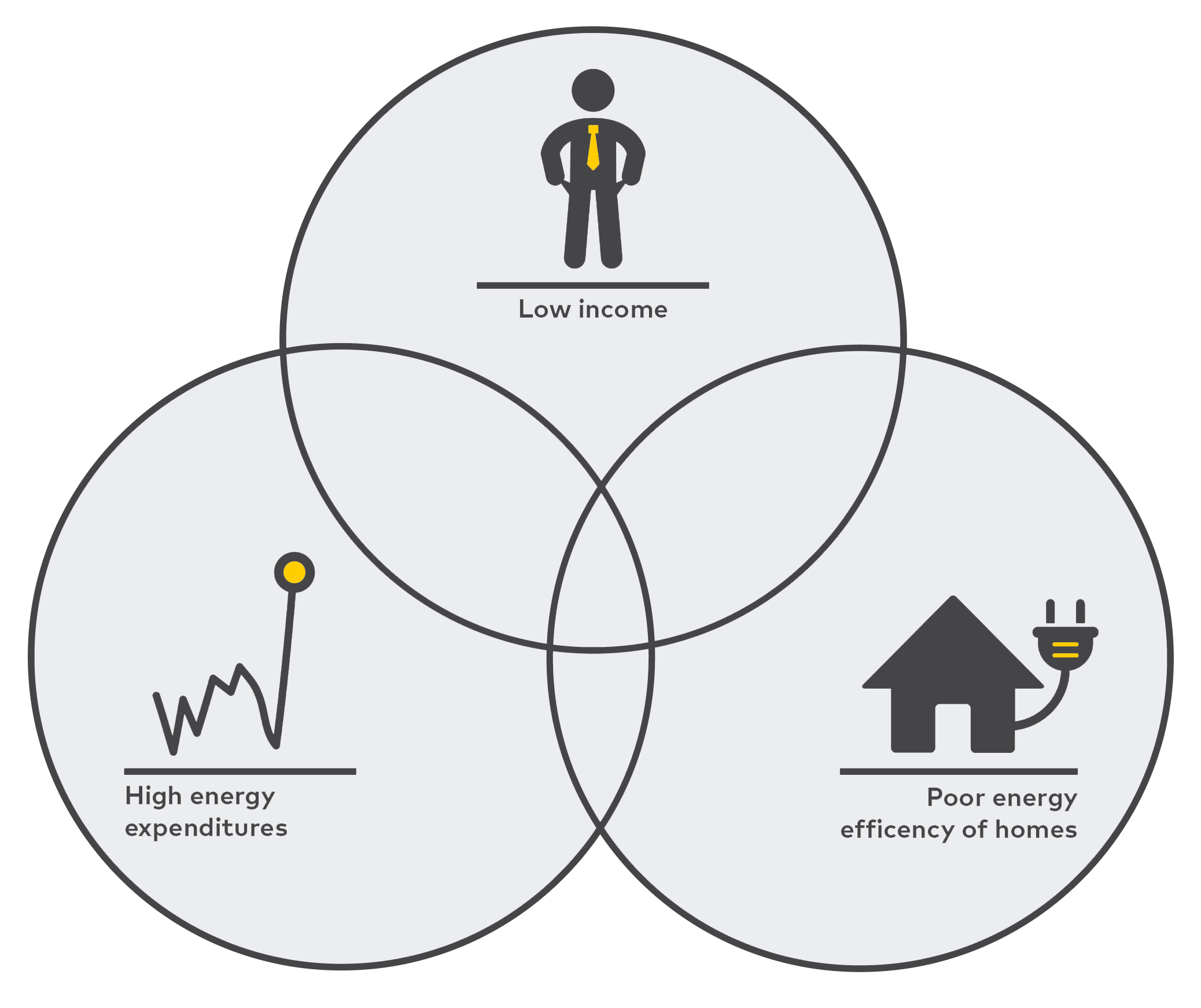

With the emerging recognition of energy poverty, it seems almost needless to say that the concept developed into a broad definition aiming to encompass the complex and multidimensional nature of the issue. Hence, the current understanding is that drivers for energy poverty vary, but often include low-income, high-energy prices, and low levels of energy efficiency as is depicted in Figure 2

To conclude, a range of indicators has been developed to capture the essence of energy poverty, but many lie at the intersection of two of the primary drivers rather than in the centre, capturing all three primary drivers. A discussion of these indicators follows in section 4.5.

Figure 2. Drivers of energy poverty

4.2 Energy poverty in the EU

The concept of energy poverty is a relatively ‘young’ concept in EU legislation. The first time the EU legislation explicitly mentioned it, was in the third energy package in 2009. Since then, energy poverty has been addressed in a range of EU legislations and working documents advising and requiring Member States to address the issue. This section summarizes some of the most pivotal work and more recent developments in the EU, serving as a backdrop for the analyses on perspectives for future work with energy poverty as described in chapter 7. The section touches upon the following EU documents:

- Electricity Directive (Directive 2009/72/EC)

- Gas Directive (Directive 2009/73/EC)

- European Pillar of Social Rights (2017)

- Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action (Regulation (EU) 2018/1999)

- Renewable Energy Directive (Directive (EU) 2018/2001)

- Energy Efficiency Directive (Directive (EU) 2018/2002)

- Clean Energy for all Europeans package (2019)

• Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action (Regulation (EU) 2018/1999)

• Renewable Energy Directive (Directive (EU) 2018/2001)

• Energy Efficiency Directive (Directive (EU) 2018/2002)

• Non-legislative measures for defining and monitoring energy poverty - Electricity Directive (Directive (EU) 2019/944) – currently under revision

- Energy Poverty Observatory (EPOV)

- Commission Recommendation (EU) 2020/1563

• Staff Working Document (SWD(2020) 960) - Communication on Tackling rising energy prices: a toolbox for action and support (COM/2021/660)

- Commission Notice on the Guidance (2022/C 495/02) to Member States for the update of the National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) due in 2023

Although the Second Energy Package, adopted in 2003, did introduce some consumer protection measures, the concept of energy poverty was not explicitly mentioned in EU legislation until the 2009 Third Energy Package. Specifically, the Electricity Directive (Directive 2009/72/EC)

In 2015, the multidisciplinary energy think-tank INSIGHT_E conducted a study on behalf of the Commission. The study investigated the ongoing work of Member States with defining and alleviating energy poverty

Continuing the work on energy poverty through the official EU institutions, the European Pillar of Social Rights (2017) stands as a pivotal document that recognises the importance of ensuring access to essential energy services, ranking it among the 20 key principles, which it delineates. Principle 20 states that “Everyone has the right to access essential services of good quality, including water, sanitation, energy, transport, financial services, and digital communications. Support for access to such services shall be available for those in need”. The pillar's insistence on the provision of support for those lacking essential services for energy is of direct relevance to the EU and Member States’ work on alleviating energy poverty. The inclusion of energy identifies its critical value for the welfare and social rights of citizens – with the cost of living and the impact that energy has across the EU currently being the number one concern for EU policy makers

4.2.1 Energy as an essential service in EU policy

Following the publication of the European Pillar of Social Rights and on the back of the EU Paris Agreement, the EU implemented the Fourth Energy Package, a wide array of new laws with respect to energy policy collectively known as the 2019 Clean Energy for all Europeans package

- Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action (Regulation (EU) 2018/1999)

- The Renewable Energy Directive (Directive (EU) 2018/2001)

- The Energy Efficiency Directive (Directive (EU) 2018/2002)

- Non-legislative measures to improve the work on defining and monitoring energy poverty

The Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action (Regulation (EU) 2018/1999), which is denoted the Governance Regulation, introduces a mechanism whereby Member States are obligated to assess the prevalence of energy poverty within their borders through National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs)

The Renewable Energy Directive (Directive (EU) 2018/2001) contributes by directing Member States to address the accessibility of self-consumption of renewable energy sources. This directive specifically highlights the importance of enabling participation in energy communities for customers residing in low-income or vulnerable households. It recognises that such households may lack the necessary up-front capital to invest in renewable energy technologies but could substantially alleviate their energy poverty through reduced energy bills.

The Energy Efficiency Directive (Directive (EU) 2018/2002) takes the general provision for inclusion of vulnerable costumers in the Renewable Energy Directive one step further by providing a framework in Article 23-24 for the inclusion of energy poor citizens in specific efficiency improvement programmes or grants. Paragraph 24 specifically recognises that energy efficiency measures are central and complementary to social security policies at Member State level, to alleviate energy poverty, alongside the need to improve energy efficiency in buildings within the objectives set out by the Paris Agreement. Furthermore, Article 7 (11) mandates that policies directed purely towards energy efficiency savings should take into account the need to alleviate energy poverty. It is noteworthy that the integration of measures relating to capital investments in the energy efficiency regulation largely validates the earlier findings of Brenda Boardman, where measures to combat energy poverty were argued to be more effectively linked to capital investments than pure income measures. The Energy Efficiency Directive was revised in 2023, and the revisions regarding energy poverty are presented in section 4.3.

In addition to the legislative measures introduced through the Clean Energy for all Europeans package, the package also introduced non-legislative initiatives to support measures to define and monitor energy poverty. Specifically, the European Commission launched the Energy Poverty Observatory (EPOV) with the purpose of improving the measuring and monitoring of energy poverty as well as sharing knowledge and best practices. EPOV has played an important role in collecting information on and discussing various indicators that measure the extent of energy poverty on a national level as well as on a local level.

The Energy Poverty Observatory (EPOV) project was followed by the Energy Poverty Advisory Hub (EPAH). (Observing energy poverty).

4.2.2 The entry of vulnerable costumers in EU policy

In tandem with the Clean Energy for all Europeans package, the Electricity Directive (Directive (EU) 2019/944)

The European Commission assumes a pivotal role in the evolution of the energy poverty agenda. Following the Electricity Directive (Directive (EU) 2019/944), the Commission was tasked with providing indicative guidance on appropriate indicators for measuring energy poverty and defining what constitutes a 'significant number of households in energy poverty’.

In response to this mandate, the Commission delivered a landmark recommendation in 2020 (Commission Recommendation (EU) 2020/1563)

Furthermore, in 2021, the Commission published the Communication on Tackling rising energy prices: a toolbox for action and support (COM/2021/660)

Building on this, the Commission continued in 2022 by issuing a Commission Notice on the Guidance (2022/C 495/02) to Member States for the update of the National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) due in 2023

4.3 Current developments

The latest work on energy poverty in the EU includes the introduction of a Social Climate Fund, the revised Energy Efficiency Directive, the revised Electricity Markets Directive and an updated Commission Recommendation and accompanying Staff Working Document.

Co-legislators adopted the Social Climate Fund Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2023/955) in May 2023

Box 1. Excerpt from Commission Notice on the Guidance to Member States for the update of the National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) due in 2023

Addressing the pressing challenges of energy poverty

Affordability is a priority of the Energy Union, and it should be reflected in the updated NECPs. All Member States are encouraged to set a clear, specific, attainable, measurable and time-bound objective for reducing energy poverty. Member States shall assess the number of households in energy poverty (Regulation (EU) 2018/1999). The Commission’s recommendation on energy poverty (Commission Recommendation (EU) 2020/1563) provides guidance on suitable indicators for its measurement. Explanation on how this definition and indicators are used and on how the data on energy poverty are collected, including at national and local level, is encouraged.

The updated NECPs should take account of the latest legislative developments, especially the proposed definition of energy poverty in the Energy Efficiency Directive and the proposed Social Climate Fund, and the above-mentioned Council Recommendation on ensuring a fair transition towards climate neutrality.

Based on such an assessment, if a Member State finds that a significant number of households are in energy poverty, it must include in its updated national plan a national indicative objective for reducing energy poverty, including a timeframe by when the objectives are to be met (Regulation (EU) 2018/1999). However, considering the current spike in energy prices, all Member States are encouraged to set an objective for reducing energy poverty. If an objective is not considered necessary, Member States should justify this decision and determine the minimum number of households that would qualify as ‘significant’ in this context. Additionally, the national plans should outline the policies and measures addressing energy poverty, including social policy measures and other relevant national programmes. Member States should outline how the objective was determined, and, to account for the current energy price spike, they should use the latest available data.

Source: 2022/C 495/02

In July 2023, the revised Energy Efficiency Directive (Directive (EU) 2023/1791) was adopted and now stands as a key document in tackling energy poverty

Box 2. Definition of Energy Poverty in the recast Energy Efficiency Directive

Energy poverty’ means a household’s lack of access to essential energy services, where such services provide basic levels and decent standards of living and health, including adequate heating, hot water, cooling, lighting, and energy to power appliances, in the relevant national context, existing national social policy and other relevant national policies, caused by a combination of factors, including at least non-affordability, insufficient disposable income, high energy expenditure and poor energy efficiency of homes’.

Energy poverty’ means a household’s lack of access to essential energy services, where such services provide basic levels and decent standards of living and health, including adequate heating, hot water, cooling, lighting, and energy to power appliances, in the relevant national context, existing national social policy and other relevant national policies, caused by a combination of factors, including at least non-affordability, insufficient disposable income, high energy expenditure and poor energy efficiency of homes’.

Source: Directive (EU) 2023/1791

In addition to providing a formal definition of energy poverty, the directive requires a stronger focus on alleviating energy poverty. The introduced changes require Member States to prioritize vulnerable customers, individuals affected by energy poverty, and citizens living in social housing when introducing energy efficiency improvements. Specifically, each Member State is responsible for achieving a share of energy savings among vulnerable customers and citizens affected by energy poverty. The directive points to four indicators measuring the extent of energy poverty (which are discussed in sections 4.5 and 5.2) that Member States should consider if they have not assessed the share of energy poor households in their NECPs. On the other hand, the Member States retain flexibility in choosing the criteria for determining energy poverty and energy savings, thus ensuring flexibility for tailored solutions based on specific needs and circumstances within each country.

In October 2023, the Commission issued an updated Commission Recommendation on energy poverty (Commission Recommendation (EU) 2023/2407)

The 2023 Commission Recommendation was accompanied by a Staff Working Document (SWD/2023/647)

To sum up, this complex web of directives, regulations, recommendations, etc. emanating from the EU reflects a determined effort to grapple with the challenge of energy poverty. Recent developments in the EU context include (1) the establishment of a Social Climate Fund. It provides financial support to Member States fulfilling their energy poverty reduction targets, (2) the first EU wide definition of energy poverty and focus on energy poor households in measures to improve energy efficiency, and (3) a Commission recommendation on implementing a national definition of energy poverty as well as guidance on the use of energy poverty indicators.

Two issues are important to note. Firstly, the EU approach to energy poverty hinges on the fundamental principle of subsidiarity

Given this diversity, the existence of a suitable EU wide approach to energy poverty is very unlikely. Rather, each Member State is tasked with defining the issue and coming up with suitable policies to address it. Secondly, the European Commission focus on energy poverty lies especially in the context of energy efficiency, decarbonisation and clean energy transition policies adopted in recent years. This contrasts with the Nordic approach, which until now primarily has focused on energy poverty from a social perspective, as will be discussed in later sections. The following section describes the status of the implementation of the directive.

4.4 Energy poverty in the Nordics

The Nordic countries are often perceived as frontrunners in terms of social welfare and relatively high levels of equality. Despite having relatively high income-levels and low levels of inequality, the recent global energy supply crisis has introduced a new scenario. This includes challenges related to affordability, housing quality, and energy sources, as well as the capacity to renovate these aspects. Consequently, end-consumers are experiencing notable price increases, placing additional strain on household budgets.

National work on energy poverty is found to be limited, which is primarily linked to the fact that all the Nordic countries have very strong social welfare systems that intend to mitigate crises economically and socially in times of crises and economic scarcity in private households. As a result, the Nordic countries have not yet developed a definition on energy poverty, and situations of economic scarcity due to rising energy prices are not distinguished from general poverty. Hence, energy poverty has been considered as a social problem addressed indirectly via social policies

Figure 3 shows the final energy consumption per capita in each of the Nordic countries in the period from 2000 to 2021, where energy consumption is observed to be relatively high compared to the EU27 average. Iceland has the largest final energy consumption in households per capita followed by Finland and Norway. The relatively high energy consumption reflects different factors, including geographical location (high heating costs), relatively high income-levels, and large transportation distances.

See for example: Nordics top world energy consumption. Nordregio. 2010.

Figure 3. Final energy consumption in households per capita, Eurostat, 2000-2021 (Kg oil equivalent)

Note: The indicator measures how much electricity and heat every citizen consumes at home excluding energy used for transportation. Since the indicator refers to final energy consumption, only energy used by end consumers is considered. The related consumption of the energy sector itself is excluded.

Source: Eurostat, SDG_07_20.

Figure 4 illustrates the development in electricity prices over time for each of the Nordic countries measured in euros, where prices increased somewhat in 2021-2022 with some seasonal variations. Prices in Denmark increased significantly more than in the rest of the Nordic countries and decreased again in the first half of 2023. Some of the general difference can be attributed to the relatively high Danish electricity tax.

Figure 4. Electricity prices for household consumers, bi-annual data, Eurostat, 2018-2023 (Euro per Kwh)

Note: All taxes and levies included. Consumption from 2500-4999 kWh – band DC.

Source: Eurostat, nrg_pc_204.

Source: Eurostat, nrg_pc_204.

The next sections summarise the work and the context on energy poverty for each of the Nordic countries and the country-specific context in terms of National Energy and Climate Plans (NECP), the general energy market situation and energy consumption by fuel types for households. It is essential to comprehend the context of each Nordic country, as it influences the characterization, identification, and treatment of energy poverty within each individual nation.

4.4.1 Denmark

Denmark has initiated the task of implementing energy poverty in a Danish context (draft NECP 2023)

In terms of ongoing work on energy poverty, The Danish Utility Regulator (Forsyningstilsynet) monitors electricity supply interruptions that are reported by trading companies (per Article 59(1) (k), (I)) of the Danish Electricity Supply Act). Based on these data, The Danish Utility Supply Authority compiles annual statistics on supply interruptions

Consumers in Denmark pay relatively high electricity taxes, and the Danish consumers are therefore subject to some of the highest electricity prices in the EU.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of Danish households’ final energy consumption across types of fuel from 2010 to 2021. It is seen that heat energy accounts for more than 35% of the final energy consumption, which is in line with a large share of Danish households that depend on district heating (approximately 64%

Figure 5. Final energy consumption in Danish households by type of fuel, Eurostat, 2010-2021 (%)

Note: Final energy consumption in households covers the energy consumption of households (individual dwellings, apartments, etc.) for space heating, water heating, cooling, cooking as well as electricity consumption by various electrical appliances. Self-produced electricity is included and counts as consumption of electricity. Self-produced heat is counted only for active systems; systems for passive heating are excluded from the scope of energy statistics. Gas oil and diesel oil are excluding biofuel portion. *No data available for ‘solid fossil fuels’ in 2014-2015 and 2017-2021. No data available for ‘other kerosene’ in 2011-2014 and 2017.

Source: Eurostat, ten00125.

4.4.2 Finland

In Finland, the prevalence of energy poverty has been estimated as relatively low. Therefore, and according to Finland’s NECP, Finland does not have any national objectives related to energy poverty and will continue treating energy poverty as a social policy to ensure all citizens’ basic necessities will be secured

Still, three studies concerning energy poverty have been conducted in Finland in 2013, 2015 and 2018. The study from 2015 examines the importance of energy poverty in Finland and estimates it to be relatively low. Moreover, the report defines the concept of energy poverty and identifies to what extent and what kind of households can be affected by energy poverty. The most affected citizens are low-income households living in large non-energy-efficient dwellings outside of urban areas. The second report combines energy poverty with the issue of improving energy efficiency in dwellings by exploring the correlation between housing improvements and the modification of heating systems in relation to the risk of energy poverty. The third report concludes that there is already a very comprehensive social support system in Finland, which has been developed to guarantee a minimum income for all – also the energy poor.

Like in Denmark, district heating is the most common form of heating in Finland, and 51% of all household buildings use district heating. Heating mode choices differ by building types; the majority of blocks of flats (89%) use district heating, while the percentage for single-dwelling houses that use district heating is only 7%. For single-dwelling houses, direct electric heating is the most common heating mode at 36%, but alternative forms such as geothermal heat and air source heat pumps have become more common during the past few years.

The purchase prices of residential heating energy for electricity and light fuel oil (heating oil) peaked in March 2022 and December 2022, which resulted in people who owned detached houses with electric or oil heating being affected by the increased energy prices.

Figure 6 summarises the final energy consumption for Finnish households in 2010-2021 by fuel type. It shows that the consumption of electricity accounts for the majority of the energy consumption. Moreover, the share of energy from heat pumps has been increasing from 2017 to 2021 while other energy sources have been slightly decreasing in the same period, which can be ascribed to the introduction of the new energy source. The share of heat also increased somewhat from 2020 to 2021, while gas oil and diesel oil have declined steadily since 2010.

Figure 6. Final energy consumption in Finnish households by type of fuel, Eurostat, 2010-2021 (%)

Note: Final energy consumption in households covers the energy consumption of households (individual dwellings, apartments, etc.) for space heating, water heating, cooling, cooking as well as electricity consumption by various electrical appliances. Self-produced electricity is included and counts as consumption of electricity. Self-produced heat is counted only for active systems; systems for passive heating are excluded from the scope of energy statistics. Gas oil and diesel oil are excluding biofuel portion. *No available data for ‘solid fossil fuels’ from 2015-2021. No available data for ‘ambient heat’ in 2010-2016.

Source: Eurostat, ten00125.

4.4.3 Iceland

Iceland differs from the other Nordic countries in terms of composition of energy system and structure of the energy market. As an energy island, the country is not connected to the European grid, but has its own independent transmission network

Due to the reasons described above, the work on energy poverty in Iceland has so far been very limited, and the country has not yet initiated work to establish an official definition of energy poverty. The updated “Report on Policies, Measures, and Projections - Projections of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Iceland until 2050” mentions neither ’energy poverty’ nor poverty in general.

Approximately 90 percent of households rely on district heating for heating their homes, which is powered by thermal energy. Also, most of Iceland’s energy comes from domestic energy production, and electricity is based almost exclusively on renewable energy (hydropower and geothermal energy).

Figure 7 illustrates the composition of final energy consumption for households in Iceland in 2010-2021 in terms of fuel type, where it is seen that heat and electricity accounts for almost all energy consumption. Gas oil and diesel oil account for a very small percentage of final energy consumption.

Figure 7. Final energy consumption in Icelandic households by type of fuel, Eurostat, 2010-2021 (%)

Note: Final energy consumption in households covers the energy consumption of households (individual dwellings, apartments, etc.) for space heating, water heating, cooling, cooking as well as electricity consumption by various electrical appliances. Self-produced electricity is included and counts as consumption of electricity. Self-produced heat is counted only for active systems; systems for passive heating are excluded from the scope of energy statistics. Gas oil and diesel oil are excluding biofuel portion.

Source: Eurostat, ten00125.

4.4.4 Norway

The recent rise in electricity prices in Norway has prompted discussions on the reach and severity of energy poverty, which until recently has not received a lot of attention. However, due to the price increases in the wake of the energy crisis, the extent of energy poverty is suspected to have increased. Like Iceland, Norway is not obliged to implement the Energy Efficiency Directive, nor to develop NECPs like the member states. Nonetheless, poverty is highly connected to climate changes and outlined in Norway’s Climate Plan for 2021-2030

Although there is currently no official definition or established measurement criteria for energy poverty in Norway, a research project called “Power Poor”, has been initiated by the Fritjof Nansens Institute (FNI) in collaboration with SBB, CICERO and the Centre for Development and the Environment at the University of Oslo

As a way of tackling vulnerable consumers, Norway has implemented a system, where the utility companies are responsible for the delivery obligation of electricity to households. The delivery obligation ensures that customers, who cannot pay their electricity bill, do not lose power in their homes

Looking at the Norwegian energy consumption in Figure 8, electricity accounts for more than 70% of the final energy consumption in Norwegian households. Hydrogen power plants account for almost all of the Norwegian electricity production

Figure 8. Final energy consumption in Norwegian households by type of fuel, Eurostat, 2010-2021 (%)

Note: Final energy consumption in households covers the energy consumption of households (individual dwellings, apartments, etc.) for space heating, water heating, cooling, cooking as well as electricity consumption by various electrical appliances. Self-produced electricity is included and counts as consumption of electricity. Self-produced heat is counted only for active systems; systems for passive heating are excluded from the scope of energy statistics. Gas oil and diesel oil are excluding biofuel portion. *No data available for ‘other kerosene’ in 2020-2021.

Source: Eurostat, ten00125.

4.4.5 Sweden

Like the other Nordic countries, Sweden does not have an official definition of energy poverty. The main reason is that the concept of energy poverty is not distinguished from poverty in general

During the energy crisis, especially the southern part of Sweden experienced a significant increase in the energy prices. Although Sweden does not have a definition of energy poverty, the Swedish authorities have defined vulnerable customers as people who are permanently unable to pay for the electricity or natural gas that is transferred or delivered to them for purposes that fall outside of business operations

Within the EU, a measure to identify households in risk of energy poverty is households who pay twice the cost of heating their home as part of their disposable income compared to what the median household pays for heating their homes. In 2021, this value was 7.5 percent for the Swedish households. This measure must be interpreted with caution in the Swedish context due to the widespread occurrence of multi-family buildings where heating costs are usually included in the rent. This constellation limits the access to data about the heating costs (access to data about 43 percent of households)

The energy consumption in Sweden consists primarily of electricity, heat, and primary from solid biofuels (see Figure 9). The structure of the electricity market zones in Sweden is divided into four different energy zones with interconnectors to different countries (Denmark, Norway, Finland, Germany, and Lithuania)

Figure 9. Final energy consumption in Swedish households by type of fuel, Eurostat, 2010-2021 (%)

Note: Final energy consumption in households covers the energy consumption of households (individual dwellings, apartments, etc.) for space heating, water heating, cooling, cooking as well as electricity consumption by various electrical appliances. Self-produced electricity is included and counts as consumption of electricity. Self-produced heat is counted only for active systems; systems for passive heating are excluded from the scope of energy statistics. Gas oil and diesel oil are excluding biofuel portion.

Source: Eurostat, ten00125.

4.5 Measuring energy poverty

As mentioned, measuring energy poverty is a component of the directive, and it has proven to be quite a tricky task. Challenges related to measuring the extent of energy poverty include diverse national and local contexts, multidimensionality of the concept, as well as data availability. Furthermore, energy poverty is a ‘private’ problem ‘largely confined to the walls of the home and is not easy to observe or follow from a public policy standpoint.’

A lot of the recent work on developing indicators in the EU context can be attributed to the Energy Poverty Advisory Hub (EPAH) and its predecessor project, the EU Energy Poverty Observatory (EPOV), both of which are initiatives run by the European Commission. Besides providing publications with guidance on how to use the developed indicators, EPAH engages with experts, local authorities and civil society organisations and provides technical assistance, underlining the importance of the national and local context. The following section largely draws on knowledge produced by these two initiatives as they are the front-runners when it comes to investigating energy poverty in a European context.

Due to the inherent complexity of energy poverty, there does not exist a single agreed upon way to measure it. Indicators can be distinguished according to type of measurement. The most common categorization referenced in several EPOV and EPAH reports and building on Thomson et al. (2017)

Box 3. Types of measurements

- Expenditure-based approach – where examinations of the energy costs faced by households against absolute or relative thresholds provide a proxy for estimating the extent of domestic energy deprivation.

- Consensual approach – based on self-reported assessments of indoor housing conditions, and the ability to attain certain basic necessities relative to the society in which a household resides.

- Direct measurement – where the level of energy services (such as heating) achieved in the home is compared to a set standard.

Source: Thomson et al. (2017)

4.5.1 Primary indicators

The EU Energy Poverty Observatory (EPOV) recommends using four primary indicators to capture a country’s level of energy poverty – two consensual-based and two expenditure-based measures - and stress that they should be viewed and used in combination

Consensual-based approach:

- Inability to keep home adequately warm: self-reported thermal discomfort.

- Arrears on utility bills: households’ self-reported inability to pay utility bills on time in the past 12 months.

Expenditure-based approach:

- High share of energy expenditure in income (2M): part of population with share of energy expenditure in income more than twice the national median

- Low absolute energy expenditure/Hidden energy poverty (M/2): part of population whose absolute energy expenditure is below half the national median.

The two consensual-based indicators originate from the EU Statistics of Income and Living Conditions (SILC) survey, collected by Eurostat on a yearly basis from Member States. The two expenditure-based indicators originate from the Household Budget Survey (HBS), also collected by Eurostat but every five years rather than annually. These surveys currently provide the best option for harmonized data across EU Member States. This is the case even though Member States are not obliged to use the specific wording proposed for the questions in the surveys, which may cause some inconsistency. Nonetheless, they provide a common foundation, which makes comparison between countries possible. As such, several Member States make use of these indicators as measures of energy poverty in their NECPs

The indicator ’inability to keep home adequately warm’ captures the feeling of material deprivation. This indicator is criticised for being susceptible to personal preferences and perceptions. What is adequate may vary with age groups or social and cultural expectations

The 2M indicator seeks to capture households where energy expenses take up a disproportionate share of the household budget. The M/2 indicator, on the other hand, aims to identify households in ‘hidden energy poverty’ that may underconsume energy due to financial inability. A crucial difference between the indicators is that the 2M indicator is based on the share of energy expenditure out of income whereas the M/2 indicator is based on absolute energy expenditures in euros. Both indicators are based on equivalized income and expenditures to account for the relative burden of varying household sizes

Using multiple indicators is essential because different measures will not necessarily identify the same group of individuals as energy poor. While the expenditure-based measures may seem intuitively more accurate, because they are not subject to individual assessments, they may struggle to identify the ‘feeling’ of material deprivation as perceived by individuals who feel that they cannot keep their home adequately warm. As an example, Price et al. (2012) shows that while there is a positive correlation between the ‘objective’, expenditure-based measure, and ‘subjective’ measure that they investigate, in many cases, they do not overlap

4.5.2 Secondary indicators and latest developments

Besides the primary indicators, several secondary indicators have been developed. Secondary indicators do not measure energy poverty directly but are related to the issue by characterizing the circumstances leading to a situation of vulnerability. EPOV presented 19 secondary indicators in their 2020 methodology guidebook, drawing mainly on data from Eurostat, SILC, HBS and the Building Stock Observatory (BSO)

The primary and secondary indicators have undergone revision and quality assessment conducted by EPAH and described in their 2022 and 2023 reports

Since the obligations stated in the Governance Regulation for the Commission to provide guidance on what constitutes a significant number of households in energy poverty, the Commission has published two recommendations, each accompanied by a staff working document (SWD), as described in sections 4.2 and 4.3. The 2020 SWD

As discussed above in section 4.3, the Energy Efficiency Directive (Directive (EU) 2023/1791) suggests four indicators of energy poverty. The indicators are:

- The inability to keep the home adequately warm

- The arrears on utility bills

- The total population living in a dwelling with a leaking roof, damp walls, floors or foundation, or rot in window frames or floor

- At-risk-of-poverty rate (AROP)

These four indicators are to be used, if Member States do not publish a set of criteria for how to determine the share of energy poor households in their national context. This requirement is likely to encourage Member States, who do not agree with these indicators being sufficient or accurate, to develop their own indicators. The 2023 SWD encourages such work and the use of national and local data sources. However, in chapter 5, some of these indicators are applied to estimate the prevalence of energy poverty in the Nordics.

In sum, challenges persist in measuring energy poverty due to diverse contexts and the multidimensional nature of the concept. The EU Energy Poverty Observatory has previously recommended four primary indicators, including both consensual and expenditure-based measures. The importance of using multiple indicators is emphasized, acknowledging that different measures may identify distinct groups experiencing energy poverty. In their 2023 recommendation, the European Commission encourages Member States to develop their own indicators if the suggested ones are deemed insufficient.

A policy brief from 2022 provides an overview of best practice examples of EU Member States’ work with defining and measuring energy poverty