PHOTOS: ISTOCK

2. INTRODUCTION

The recent energy crisis in 2021-2023 and subsequent rapid energy price increases have challenged societies and put pressure on consumer budgets all over Europe. At the same time, repercussions of the global COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical developments and energy supply challenges have exposed risks in the energy sector and demonstrated that shocks to energy markets are not necessarily distributed evenly across society.

Consequently, energy poverty – once considered a marginal concern in the Nordic region – has emerged as a focal point on the political agenda, and countries have responded by implementing emergency measures to mitigate the negative consequences on populations. Energy policy and social politics have converged, necessitating a comprehensive understanding and proactive measures to navigate the complex challenges of ensuring a sustainable and just transition of the Nordic energy sector moving forward.

In short, energy poverty refers to a situation where households or individuals are unable to secure, either financially or through physical utilities, an adequate level of energy services for their home

While energy poverty has been debated in a European context for several years, the energy crisis has reconfirmed energy poverty as a serious political issue in the European Union (EU). In recent years, the EU has intensified its ongoing initiatives to identify and mitigate energy poverty within Member States

In response to the above-mentioned situation, Nordic Energy Research (NER) – acting on behalf of the Electricity Market Group (EMG) under the Nordic Council of Ministers (NCM) – has called for an examination of energy poverty within the Nordic context. The motivation behind this inquiry is twofold: firstly, to expand the knowledge base that is essential for informed policymaking; and secondly, to provide substantive support to the Nordic countries in their efforts to alleviate energy poverty.

This report delves into the paradigms, definitions, indicators, and current state of energy poverty in both the Nordic countries and within a broader European Union context, shedding light on the intricacies of the issue itself and proposing avenues for effective policy interventions. Through a comprehensive exploration of the current landscape, this report aims to contribute to the ongoing dialogue on energy security, social equity, and sustainable development in the Nordic region.

2.1 Context

National as well as global climate goals combined with challenges of energy security have intensified the need to decarbonise energy systems around the world

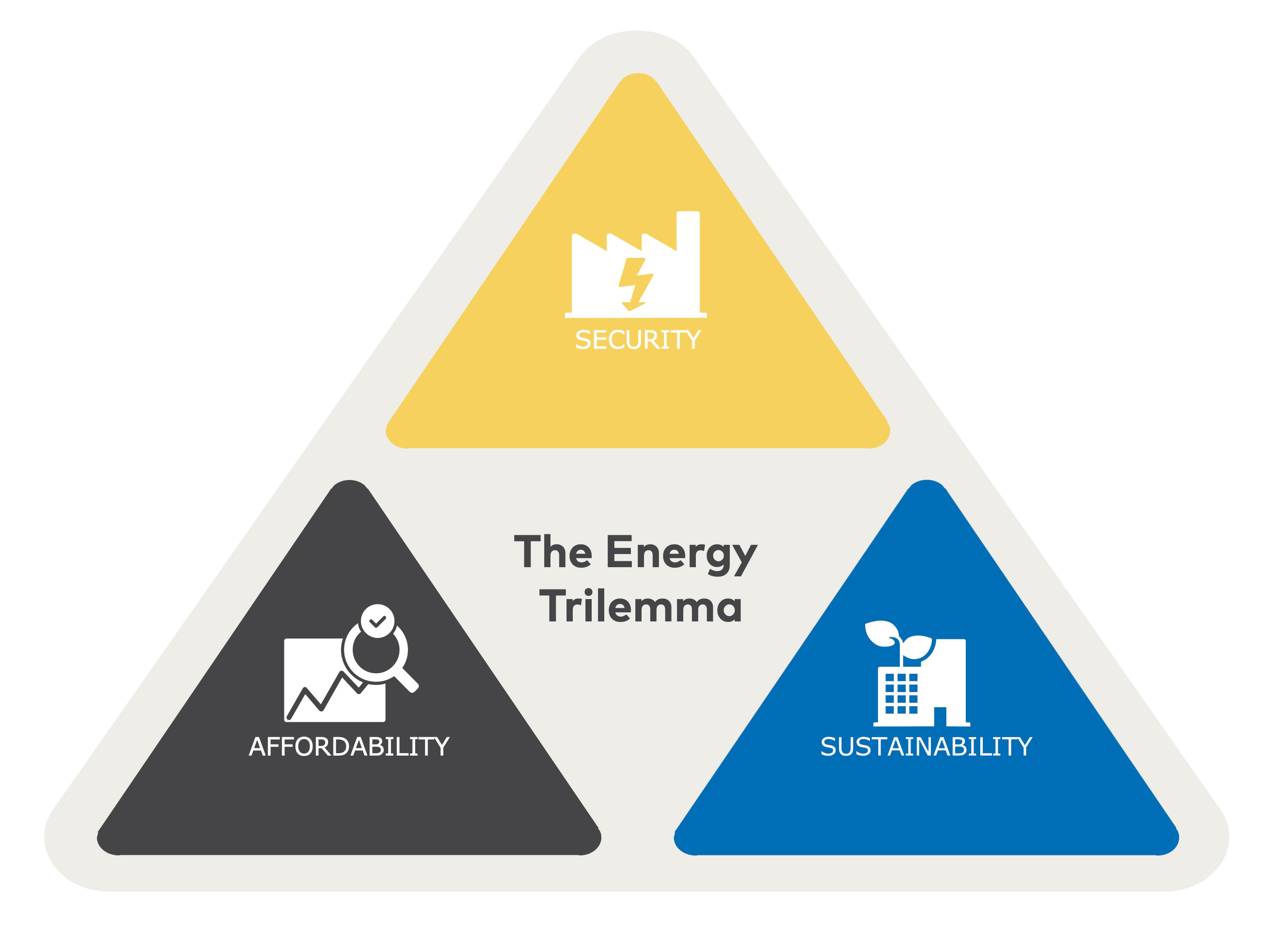

Hence, the concept of energy poverty is closely linked to the energy trilemma because it is not only a matter of affordability and broader social resources but also concerns topics such as energy sources, energy security, and energy efficiency.

Figure 1. Illustration of the Energy Trilemma

Source: Figure taken directly from The Nordic Energy Trilemma (norden.org)

The recent energy trilemma report by NER (2023) evaluates the drivers and amplifiers of the energy crisis, along with Nordic countries’ level of exposure, preparedness, and responses

DRIVER | Denmark | Finland | Iceland | Norway | Sweden |

Electricity market structure | |||||

Decommissioned controllable electric capacity | |||||

Electricity supply and demand balancing | |||||

Lack of electric grid infrastructure | |||||

Inflexible electricity demand | |||||

Weather-dependent energy supply | |||||

Increasing energy import dependency | |||||

Natural gas supply reductions |

Table 1. Risks/exposure of the Nordic countries

Source: “The Nordic Energy Trilemma. Security of Supply, Prices and the Just Transition” Nordic Energy Research, 2023, .

Note: Red = High risk, Yellow = medium risk, Green = low risk, Grey=no effect.

Note: Red = High risk, Yellow = medium risk, Green = low risk, Grey=no effect.

Considering the multiple risks associated with a disruption of the energy system, the risks posed specifically to consumers are varied and come from multiple directions. It is therefore crucial for policy makers not only to be aware of these risks based on the best available data, but also to be ready to react in a timely manner and to mitigate their impact. Further, the risks posed to consumers are not evenly distributed: Vulnerable groups (e.g. poor health, limited social and personal resources), and groups with less economic resources, are often more exposed to risks and have less resources to mitigate crises resulting from supply reductions or price peaks. Agreeing on definitions of energy poverty before a future crisis and methods for measurement, can contribute to ensuring a sufficient response to impacts specifically on vulnerable groups. This is also important when addressing the affordability perspective in the energy trilemma.

The consideration of vulnerable groups is not just a result of the current supply crisis. As mentioned, countries also have high ambitions to decarbonise due to the unfolding climate crisis. This means a transformation of the way in which the world’s energy systems work, whilst balancing the trilemma: new greener energy sources and systems must be reliable and secure to prevent disruptions in energy supply