2. AS-IS

2.1 Description of requirements

While setting out to create a predictable regulatory environment for trust services and ensuring that people can use their own national electronic schemes to access public services online in other EU countries, the state of play demonstrates shortcomings to the full implementation of the eIDAS regulation. As the implementation date for the SDGR and its 21 prescribed online procedures approached, national administrations faced a dual challenge of enforcing two complex and resource demanding regulations. However, as the eIDAS and SDGR are interrelated, the challenges prove similar for many countries. Resolving the central obstacles through cross-border cooperation is the key. One of these obstacles is identity matching.

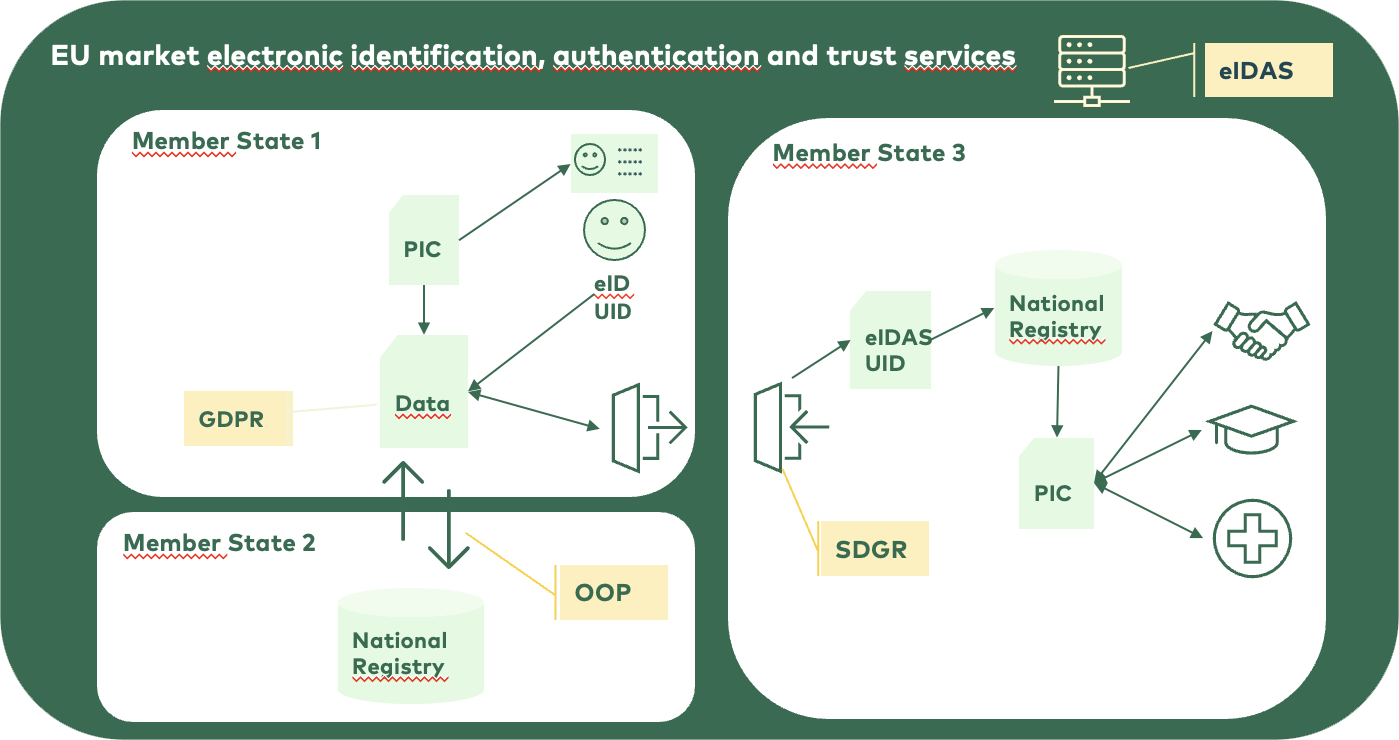

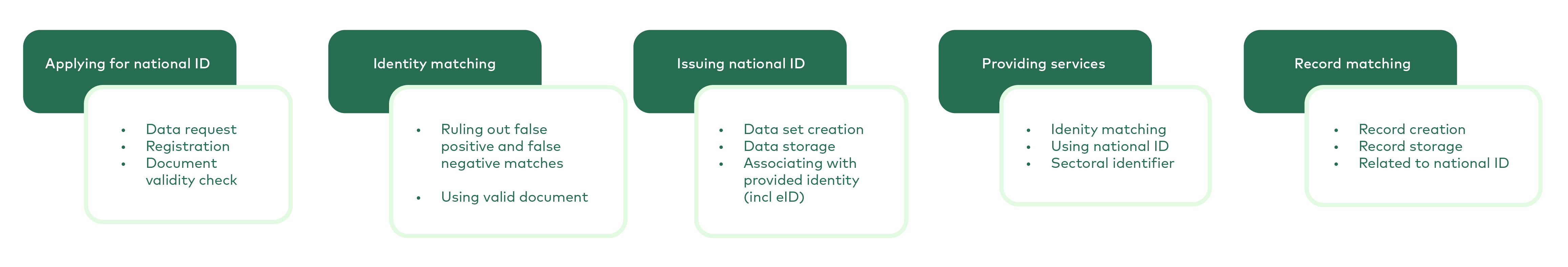

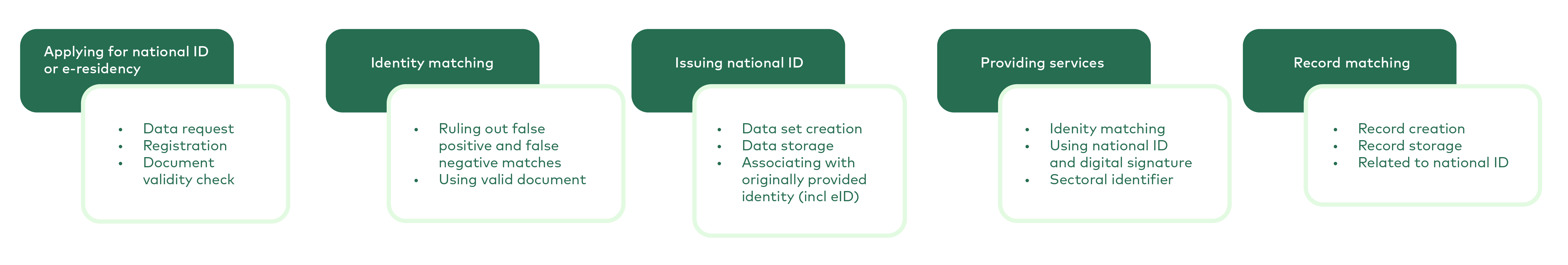

Figure 1 Identification matching areas affected by regulations (eIDAS, SDGR, OOP, GDPR).

Figure 1 illustrates what areas of identification and record matching are affected by regulations described below in this chapter. For the sake of the volume of this document and because of wide coverage of the topic elsewhere, the in-depth description of GDPR is not included. However, GDPR and identity matching are related because identity matching processes often involve the handling of personal data, and GDPR provides the legal framework for the protection of personal data within the European Union. Organisations conducting identity matching activities must comply with GDPR regulations to ensure the privacy and security of individuals' personal data.

2.1.1 eIDAS – electronic IDentification, Authentication and trust Services

The eIDAS Regulation:

- ensures that people and businesses can use their own national electronic identification schemes (eIDs) to access public services available online in other EU countries.

- creates a European internal market for trust services by ensuring that they will work across borders and have the same legal status as their traditional paper-based equivalents.

The first version of eIDAS was ready in 2014 and implemented in 2016. Now, the Commission is already working on an updated version. The Commission proposal amends and updates the existing eIDAS Regulation by responding to the challenges raised by its structural shortcomings and limited implementation and to technological developments since its adoption in 2014.

The reason for updating the regulation was that not all eID key interoperability components of the older version of eIDAS were obligatory for EU Member States. As a result, only 14 of them completed their eID schemes which were all different. The new provisions will be mandatory for countries, which punishes those who have already achieved more and makes finding a common solution quite difficult. Madis Ehastu, Estonian Seconded National Expert at the European Commission who is actively developing the new eIDAS regulation, said that one of the key difficulties lies in finding common approaches considering substantial variations in legislations and cultures.

Regarding identity matching, eIDAS requires that electronic identification means used for cross-border transactions must be reliable and secure, and the identification of the user must be verified using robust authentication mechanisms. This means that the eID system must use methods that can confirm the identity of the user with a high degree of certainty and establish rigid issuance process and lifecycle management of electronic identities.

Additionally, eIDAS requires that the identification process must be carried out in compliance with data protection laws, with due regard for the privacy and security of personal data. This includes ensuring that the user’s personal data is processed only for the purposes of identification and that it is not disclosed to unauthorized parties. Furthermore, eIDAS also sets out specific requirements for the electronic identification means themselves, including technical specifications for the security features and mechanisms used for protection against unauthorized access and data breaches.

Identity matching is typically done by looking up and matching the identity received with the identities registered. For this purpose, the eIDAS Unique Identifier (eIDAS UID) can only be directly used if it is already known by the Evidence Provider. This may be true in cases where the Evidence Provider has already linked the eIDAS UID to a known identifier or has access to such a record. The eIDAS UID is a mandatory attribute in the minimum set of person identification data specified in the EC implementing regulation,

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/1501 of 8 September 2015 on the interoperability framework pursuant to Article 12(8) of Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market

Notwithstanding the mandatory stipulation of the eIDAS UID, the persistency of eIDAS UID is not enforced and as consequence undermines its uniqueness characteristics. Some Member States issue an outbound identifier for each Member State, which is also usually derived. This means that the third part of the Unique Identifier, the combination of readable characters, may not have the same value for all requesting Member States. This means that in such cases, the eIDAS UID (PersonIdentifier) was issued for the specific context of the Online Procedure Portal, and it cannot be used by the relying party (Data Service).

How these outbound identifiers are generated is specific to each Member State and/or eID means. The derivation process could potentially prove challenging (or impossible even) for a matching function from the issuing Member State to identify the user based only on this identifier. Additional attributes may be needed. The information on the Unique Identifier, if it is derived and/or receiving Member State specific is communicated during the notification procedure and in the following resource. This information could be requested from the eIDAS Cooperation Network and configured accordingly.

2.1.2 SDGR – Single Digital Gateway Regulation

The purpose of the Single Digital Gateway (SDG) is to

- reduce any additional administrative burden on citizens and businesses that exercise or want to exercise their internal market rights, including the free movement of citizens, in full compliance with national rules and procedures,

- to eliminate discrimination and

- to ensure the functioning of the internal market regarding the provision of information, of procedures, and of assistance and problem-solving services.

The Regulation makes it mandatory for Member States and EEA countries to provide access to 21 digitalized administrative procedures in a safe and convenient way. The procedures include (amongst others): requests for a birth certificate, vehicle registration, starting a business or submitting a corporate tax declaration.

Full list of services is available in the Annex II of SDGR: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/TodayOJ/

The SDGR sets out several requirements related to Identity matching, which are detailed in the following paragraphs:

- Secure and reliable electronic identification: The SDGR requires that electronic identification means used for cross-border transactions must be reliable and secure, and the identification of the user must be verified using robust authentication mechanisms. This means that the eID system must use methods that can confirm the identity of the user with a high degree of certainty, such as biometric authentication or multi-factor authentication. The regulation requires that the eID means used must be certified under the eIDAS Regulation. This ensures that the eID system complies with strict security and privacy requirements.

- Reuse of existing data: The SDGR requires that public authorities must use existing data and information collected from other public authorities whenever possible. They must avoid collecting the same information from citizens and businesses more than once unless the information is necessary for a specific purpose.

- Limited collection of personal data: The SDGR requires that public authorities limit the collection of personal data to what is necessary for the provision of a specific public service or the fulfilment of a specific legal obligation. They must not collect more personal data than necessary or retain it for longer than necessary.

- Protection of personal data: The SDGR requires that public authorities protect personal data from unauthorized access, disclosure, or misuse. They must comply with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and other data protection regulations when collecting, processing, and sharing personal data.

- User consent: The SDGR requires that public authorities must obtain the explicit request of the user before collecting, processing, or sharing their personal data. Users must be informed about the purpose of the data collection, the legal basis for the processing, and their rights under data protection laws.Regulation (EU) 2018/1724 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 2 October 2018 establishing a single digital gateway to provide information, procedures, assistance and problem-solving services and amending Regulation (EU) No 1024/2012

Cross-border OOP will become a reality in the EU at the end of 2023, when the Member States are expected to finalize the integration of the 21 online procedures with the OOTS.

The procedures in directives listed in SDGR article 14.1 also must be integrated with OOTS i.e., Service directive, Professional qualification directive and Procurement directives.

Access to the gateway will be available via the search function of the Your Europe portal, which has existed since 2006 to provide citizens and businesses information on EU and national rights. The establishment of a single-entry point will contribute to a more comprehensive and user-friendly package of information and assistance, which will help EU citizens and businesses navigate the internal market. Furthermore, the gateway will be conducive to more transparency in terms of rules and regulations relating to different business and life events.

2.1.3 OOP – Once Only Principle

The principle states that:

- citizens and businesses should only be required to provide information to public authorities once, regardless of how many times that information is needed by different public authorities.

- Under the OOP, public authorities must share information and collaborate with each other to ensure that data is collected only once and reused by other public authorities as needed. This means that citizens and businesses do not need to provide the same information repeatedly, which reduces the time and effort required to interact with public services.

The OOP applies to all EU member states and covers a range of public services, including social security, taxation, and starting a business. It is intended to promote the efficient use of public resources and reduce the administrative burden on citizens and businesses. The implementation of the OOP requires the use of advanced digital technologies and interoperable systems to enable the sharing of information between different public authorities. This includes the use of electronic identification and authentication systems, secure data exchange platforms, and data protection measures to ensure that personal data is processed securely and in compliance with data protection regulations.

The main objective of the OOP – reducing the administrative burden of users and businesses by re-organizing public sector internal processes – derives directly from the overall political objective of improving economic efficiency of the EU by facilitating cross-border trade through such initiatives as digital single market.

EU eGovernment Action Plan 2016-2020.

- different understanding of the once-only principle,

- different approaches to public service provision,

- different IT systems that make such services possible,

- but also, different understanding of issues relevant to the once-only principle, such as protection of personal data, for example.Krimmer, R., Kalvet, T., Toots, M., Cepilovs, A. and Tambouris, E., 2017. Exploring and Demonstrating the Once-Only Principle: A European Perspective. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research (pp. 546-551). ACM.

While the OOP does not specifically regulate identity matching, it can impact the way in which identity matching is performed in cross-border transactions. In general, the OOP requires that public authorities should only request information from citizens and businesses once and should make efforts to reuse this information for subsequent transactions, provided that the information is still up-to-date and relevant. This can include personal information such as identity documents and tax identification numbers. When implementing the OOP, public authorities must ensure that they comply with relevant data protection laws, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and that they have appropriate measures in place to ensure the security and privacy of personal data.

European Commission. (2020). European Interoperability Framework - Implementation Strategy. Brussels: European Commission.

2.2 Technological readiness

2.2.1 Data required for identity and record matching

When people are moving, working, or studying abroad, it is usually only a matter of time when some services are needed while being in another country. Even though people are moving across borders more and more,

The Nordic Statistics database. (2020, October 30). Who goes where in the Nordic region?

Three different scenarios of three different fields were studied and are described below:

- opening a bank account in another country

- identifying the person and accessing past medical history

- recognition of professional qualifications

These three scenarios are described from the two main aspects of technological readiness: data and actors.

Banking: opening a bank account in another country

Opening a bank account is a process that involves identification of the person and collecting data related to the person’s financial behaviour. Process must follow EU’s anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) rules.

Preconditions for opening a bank account vary depending on the chosen registration method. A physical presence in the bank office is suitable for all persons who qualify with banks’ general terms. Usage of e-services with eID means for same purpose does impose significant limitation. Namely the eID mean issued within country of bank’s residence is commonly required and must be complemented by person’s physical ID-document. The latter can be either a person’s national ID-document or the one issued by authorities of bank’s country of residence.

Availability of personal identification number issued by the county where the bank is operating is crucial for identity verification. Imposed limitations for e-services channels are justified with strict requirements coming from AML/CTF rules, and risks coming from cross-border identity matching based on eID means can be seen as un-acceptable liability considering potential operational, financial, and reputational damages. Thereof person’s eID mean originating from a country other than a bank’s residence country cannot be used for onboarding through e-services.

Data

Data collected during the opening of bank account through eID mean supported e-service must enable identity verification (1:1) of the person in the context of banks’ country of residence.

Data collected from eID mean comprises of following attributes:

- family name(s)

- first name(s)

- date of birth

- personal identification number

Data available from person’s physical ID-document:

- family name(s)

- first name(s)

- date of birth

- place of birth

- document number

- personal identification number in document issuing country.

- citizenship

In addition to personal identifiable information (PII) banks do request data that enable fulfilment of due diligence defined by AML/CFT rules.

Additional data presented by person:

- contact address (formal/informal)

- types of incomes

- tax payment countries

- expected monthly incomes and cash transaction amounts.

- accounts in other banks

- other country’s regulation specific data

Actors

Table 1 Opening a bank account in another country actors and responsibilities

Actor | Action | Necessary preconditions, successful authorization of: | Successful identification/authentication of: | Other directly involved' actors |

Customer from country A | Identifies him/herself in bank of country B | eID mean issued in country B. Possession of physical ID-document | Authentication with eID mean issued in country B. Validity checks and verification of presented physical ID-document | eID provider in country B Database of stolen or lost documents (country of document’s origin or Interpol SLTD (stolen or lost travel documents) database Identity proofing service provider of bank |

Bank in country B | Validates PII retrieved from eID mean and physical ID-document. Validates additional data submitted following AML/CFT rules | All requested customer related data is made available to bank | PII and additional data are successfully validated against population registry and potential black/grey lists of banks. Additional data meets criteria established by AML/CFT rules | Population registry of country B |

Customer from country A and bank in country B | Entering contractual relationship | PII is validated and AML/CFT rules fulfilled. | Acceptance of bank’s terms and conditions by customer. Signing of contract by customer and bank. |

To conclude, cross-border usage of eID means is not supported for opening a bank account in another country. Limitations coming from AML/CFT rules force banks to restrict account opening e-services to accept only eID means issued within the residence country of the bank.

Health: identifying the person and accessing past medical history

Treatment of patients without proper information on the patient’s medical background and history poses a lot of risks. There are already ongoing collaboration and practices between the Nordic and Baltic countries. A good example of an already working operational solution is the ePrescription exchange between Finland and Estonia. There are also projects such as the health care and care through distance spanning solutions – project (VOPD) led by Sweden.

Healthcare and care at distance. (n.d.). Healthcare and care through distance spanning solutions

Data

Today, European cross-border health data exchange consists of two services:

- cross-border digital prescription and

- patient summary

These two services are a part of eHealth Digital Service Infrastructure (eHDSI)

The eHealth Digital Service Infrastructure (eHDSI or eHealth DSI) is the initial deployment and operation of services for cross-border health data exchange under the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF)

The most important entities of eHealth DSI system are human beings (patients, HPs, administrators, etc.). However, there are many non-human entities in the eHealth DSI. The most important of them are documents in electronic form, which are of course always linked to a human entity.

Example (data related to human entity): Daniela Altenberg, born 29.12.1979 in Vienna, Austria, Father Gottfried Altenberg (*6.6.1953), Mother Elisabeth Altenberg (*6.3.1956, maiden name Eugenie) address of residence Vienna, Castle of Schönbrunn, No 1.).

Identity matching is completely a responsibility of the health care provider. For example, in Estonia, HCP must make an enquiry to a patient’s previous home country, previous home country checks from the population register whether a person has personal identification number, the person is alive and has allowed to share its medical records. Patients themselves don’t have electronic access to their previous medical records with foreign country’s ID.

However, patients still can request an extract from the medical records.

Within the eHealth DSI environment physical identity sources (passport, ID, diploma etc.) can be used within identification and authentication processes. At least two-factor authentication

eID authentication: ID number + password or electronic ID card.

It is the responsibility of each country to upload its own International Search Mask (ISM), to the configuration settings of the platform. And then this Search Mask clarifies what information about one’s patient needs to be asked to uniquely identify a patient, which varies a lot among countries. Many countries have just one ID: it can be a personal identification number, or document number, social security number etc. However, some countries use multiple.

The eHealth DSI environment is a set of National Contact Points (NCP) communicating by means of public networks. NCPs are interfaces or proxies between national eHealth domains. These national eHealth domains are not under direct control of eHealth DSI. Patient data and identities of patients, HPs, HCPOs are placed in registries, repositories, or databases in national domains and most of the data processing takes place there. Therefore, it must be distinguished between processes running in the intrinsic eHealth DSI environment and the processes running partially or totally outside the intrinsic eHealth DSI environment within the national domains. eHealth DSI and authorities/participants from national domains will together provide identification and authentication services.

The intrinsic eHealth DSI identity confirming and forwarding covers the following points:

- Management of selected identity datasets and/or identifiers:

- of single persons (HP, patient).

- of a group of persons (legal entity of healthcare providers, e.g., HCPO).

- of single documents (patient consent).

- Management of outgoing requests for validation of provided identities within the “Circle of Trust.”

- Management of incoming requests and responses to such requests.

- A secure, trustworthy, and reliable acknowledgement and vouching for the correctness of information provided by the national infrastructure and the HPs.

National authorities and institutions from national domains will provide:

- the accurate management of identities lifecycle, from the creation of identifiers of entities until they terminate.

- the accurate management of identity assurance, authentication of the identity information, and the assessment of the required level of risk assurance for collecting and using identity information (named “trust level” in the following descriptions).

- the accurate management of identity information at the level of the relevant identity authorities and.

- the accurate management of local systems and/or services which support the “Circle of Trust” (NCP).

The eHealth DSI services include the transfer of sets of agreed data, particularly, a patient summary, that also includes a medication summary and data related to the ePrescription (prescription and dispensation). Most of the data included in those sets correspond to health data and therefore these documents are referred to as health data. Utilizing eHealth DSI services to access health data is contingent on successful identification and authentication of the health care professional, the identification of the patient, the fact that the eHealth DSI system “knows” the appropriate documents and the requestor is assigned to a role which is authorized to gain access to eHealth DSI.

Currently, only patient summary is digitally accessible cross-border, provision of other medical data is the responsibility of the patient (printing out the medical history, translation etc.). Currently, the patient summary dataset must include active health problems, diagnosis codes and history of previous diseases. Optional content includes blood pressure data, blood group and rhesus factor data, allergy data, facts about smoking and alcohol consumption, and surgeries and procedure data. The patient summary is more of a standardized dataset that can be provided in a coded form. And in many countries provision of even this data is not possible yet.

Actors in MyHealth@EU

The following table summarizes the relevant activities of actors belonging to eHealth DSI roles (according to the basic scenario – HP from Country B needs patient’s health documents from patient’s home Country A). eHealth DSI is based on distributed systems and many functions will be executed by actors within national domains. The eHealth DSI role management depends strongly on cooperation with national authorities and operators of local systems. (See Table 2)

HCPO: In every country involved in eHealth DSI a national authority or a group of regional authorities must exist, able to define/manage HCPOs from its domain, participating in eHealth DSI. NCP will communicate with the respective national authority to keep the actual list of HCPO. eHealth DSI would define the minimal set of information necessary for unambiguous identification of HCPO.

HP: HPs identities will be managed in national domains. A national authority will maintain the list of all HPs in its domain and provide it to its national NCP. HCPO will provide NCP the roles assigned to its HP (if necessary). eHealth DSI would define the minimal set of information necessary for unambiguous identification of HP.

Patient: Each use case accessing the patient data, such as the Patient Summary and ePrescription/eDispensation use cases, requires the minimal set of necessary information for identification of a patient.

Authorized Third Party (optional): For member states allowing it, an authorized third party can perform any action the patient can perform.

Health data administrator: A health data administrator is primarily responsible for running systems which exchange health data on NCP. The second responsibility covers the support of patients whenever they want an extract of audit log data. Health data administrators are working for or on behalf of national authorities and from an eHealth DSI point of view the standard professional and security requirements fully suffice for this role.

Table 2 MyHealth@EU actors and responsibilities

Actor | Action | Necessary preconditions, successful authorization of: | Successful identification/authentication of: | Other directly involved actors |

HP B | Requests services from Country A | HP in Country B | HP in country B the patient by Country A | National Infrastructure B, NCP B NCP A |

Patient | Requests check and provision of audit log concerning the accesses to his health data | Successful authorization of HP | authentication of the patient at PoC | NCP A, Health data administrator |

Authorized Third Party (optional) | For the member states allowing it, can perform any action the patient can perform | Successful authorization of HP and authentication of the patient at PoC NCP-B and NCP-A must both authorize a third party to act on behalf of the patient | patient at PoC | Patient, NCP A, Health data administrator |

NCP B | Requests services from Country A | Successful identification and authorization of NCP A Authentication of the patient | NCP in county B The patient by country A | NCP A |

NCP A | Responds to service requests of NCP B | Successful identification and authentication of NCP B Authentication of the patient Authorization of HP/HCPO | The patient by country B NCP A | NCP B Identity authority managing the databases of patients, HPs, HCPOs |

HCPO or other external service provider | Provides required information to NCP | Mutual successful authentication of both parties | Both parties | NCP B HCPO or other external service provider |

Health data administrators | Administrate systems processing data and pro- vide some services (e.g., excerption of audit logs) | Successful identification of health data administrators Authentication of health data administrators Assigning the role of health data administrators | Health data administrator | NCP or HCPO |

EHDSI- Identity Management in MyHealth@EU

In many countries, not all the health care providers have joined with the services, so for example in Netherlands, there is currently just one Hospital that uses eHDSI. Main concerns for many countries are data security, trust issues and encryption used. Standards, privacy issues, technologies and translations are decided and included in eHealth Digital Services Infrastructure and the decisions made already in eHDSI are preferences for many countries.

It is planned that in 2025–2026, the technical prerequisites for the European Commission's central solution will be created, so it will be possible to share laboratory analysis data, hospital treatment summary data, medical records, and test response data.

Academia: recognition of professional qualifications

Professional recognition is the appreciation of a foreign qualification for the purpose of employment in a certain profession. The recognition of qualifications for professional (employment) purposes depends largely on whether the profession in question is regulated or is not regulated in the host country.

Data

IMI allows competent authorities to check data within the EU by making inquiries to other countries’ competent authorities and verify the data. ENIC/NARIC Network allows to make an analysis on a diploma and gives assurance about the higher education institution and confirms that the diploma was issued to a particular person.

However, there are no general rules for identification of persons. Competent authority generates a deed of identification that is not shared amongst other competent authorities and is not updated in case of personal data changes. So, if a person has different qualifications in different fields, one must go through two separate processes for identification and recognition of foreign qualifications.

Actors

Depending on the field of study, different competent authorities (usually ministries, professional associations, etc.) must evaluate a person’s qualification according to the Directive 2005/36/EC.

Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 September 2005 on the recognition of professional qualifications

Table 3 Recognition of foreign qualification, actors and responsibilties

Actor | Action | Necessary preconditions, successful authorization of: | Successful identification/authentication of: | Other directly involved actors |

Person (from country) A | Requests diploma recognition from country B | Person identification following Competent Authorities requirements Presenting diploma | Person A in Country B | |

Competent Authority of country B | Verifies diploma data and qualification | Data exchange system (IMI, ENIC/NARIC) | Competent Authority of country A | |

Competent Authority of country A | Confirms diploma data and qualification | Data of diploma | National data sources for educational and qualification records in country A | |

Competent Authority of country B | Issues deed of recognition | Diploma data and qualification confirmed by Competent Authority of country A |

Currently, competent authorities are mainly using ENIC/NARIC

2.2.2 An analysis and discussion of the availability and machine-readability

Based on three different scenarios of three different domains studied and are described in chapter 2.2.1, one can see remarkable challenges to be tackled if cross-sectoral data availability and data machine-readability would be targeted. Main aspects that must be confronted would be following:

- Implemented systems do vary from country-to-country dependent on availability of resources and/or volumes of cases. In addition, within the country implementations in sub-domains of specific domain may have significant discrepancies.

- Identity management processes are defined following requirements and risks-imposed domain. Requirements for identifying persons can be missing although the domain is regulated on EU-level, and matching identity with record is crucial.

- Domain specific data is not deployable for cross-sectorial usage, as it is commonly prohibited due to data protection constraints, data can be non-disclosable for reason of being a business/bank secret.

- Data is handled by numerous competent authorities, who have their own registries. Data is not often shared to allow automated processes for further use based on the received (digitized) data.

- Personal identifiable information at rest in most domains’ registries is not updated if any change in attributes occurs.

- There are EU level systems for domain specific communication and data exchange, but their interfaces are designed differently. Besides human-to-machine interaction human-to-human interfaces are still deployed. Human-to-machine interface does provide better options for data machine-readability, whereas human-to-human interfaces exploit free text data fields, and no format harmonization has been achieved either for evidence exchanged as digital files. A lot of cross-border identity and record matching is based on paper documents and manual work.

- Implementations are made to solve single domain specific use cases at the time and do not scale nor provide reusability of data.

To sum up the aspects provided above, it can be stated that availability and machine-readability of data is constrained by existing implementations and legislation. Thus, deploying them as-is for a large-scale identity and record matching is not feasible.

From identity and record matching perspective it should be targeted, that personal identifiable information is handled in cross-domain use cases in a manner that enables deployment of harmonized principles facilitating the matching necessities. Providing solution, which centrally deals with identity management (creating identities accompanied by adequate attributes, mechanisms for updating the attributes (while keeping initial values) and enriching identities with attributes originating from other countries (e.g., personal identification numbers) and is available for cross-domain usage should be focused on.

2.2.3 Description of identity matching in the Once only technical system

To date all countries have opted to consider unique user only within a member state. Linking data between member states based on user attributes (see Table 4) is almost non-existent.

The technical and operational specifications of the Once-Only Technical System (OOTS) is laid down in the European Commission’s Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/1463. Regulation (EU) 2022/1463 foresees usage of eIDAS nodes for cross-border authentication of a user by electronic identification means issued under electronic identification schemes notified in accordance with Regulation (EU) No 910/2014.

eID schemes from the Member State of the Evidence Provider, which are deemed adequate for the access to the Evidence Providers' services may also be relied upon. This includes both notified and non-notified eID schemes.

Identity matching is the role and responsibility of evidence providers following Regulation (EU) 2022/1463. Evidence providers’ application services shall be capable of identifying the user through eIDAS node, perform matching of PII with identities known to evidence providers and retrieving correct identity evidence from their records. Evidence providers may require users to provide additional attributes beyond the mandatory attributes of the minimum data set listed in the Annex to Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/1501 for the purpose of identity and evidence matching. Referenced additional attributes can be either optional attributes of the eIDAS minimum data set and/or sector specific attributes that may be made available via the eID scheme used, if it is allowed by the national law and if the user gives their consent for this purpose. However, the use of eIDAS node does not preclude the use of other mechanisms to provide complementary or additional security measures.

It is mandated that evidence can be processed only in case identity matching generates single result.

Neither Regulation (EU) 2022/1463 nor OOTS Technical Design Documents do specify methods for identity matching. OOTS Technical Design Documents do acknowledge the variety of combinations of how personal identification numbers may be presented through eIDAS node (personal identification number being derived or not, derivation receiving Member State specific or not), but logic design for handling various combinations is left up to national implementations.

Hereby table of Identity attributes will be compiled to illustrate possibility of finding common solution for Nordic-Baltic countries (Table 4).

Table 4 Identity attributes of European countries

COUNTRY | EIDAS BASIC DATASET | ADDITIONAL ATTRIBUTES | ||||||||||||

EUID | FIRST NAME | FAMILY NAME | DATE OF BIRTH | GENDER | OTHER NAMES | NATIONALITY/CITIZENSHIP | COUNTRY | PLACE OF BIRTH | CENTURY OF BIRTH | CURRENT ADDRESS | BIOMETRY | FIRST NAME AT BIRTH | LAST NAME AT BIRTH | |

Estonia | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

Spain | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

Luxembourg | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

Netherlands | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

Norway | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

Lithuania | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

Exceptional in this regard is cross-border data transfer between Nordic countries based on population registry and connected to migration data. There are procedures where a new address in a new member state of the person moving out from a country is listed automatically to the population registry of the country person migrated from.

2.3 A state of play of processes and solutions for identity and record matching in the EU/EEA.

The development of a European digital identity is not new. The 2014 eIDAS regulation has set standards for digital identification methods across the European Union (EU) for citizens and legal persons. The goal of this regulation is to strengthen the European Single Market by promoting confidence and convenience in cross-border electronic transactions. These benefits have not come to fruition as initially planned: since the regulation came into effect in September 2018, only 59% of the EU population (living in 14 Member States) can use an electronic national identity document cross border. To achieve the eIDAS’ goals, the Commission has proposed an amendment of the regulation (eIDAS 2.0) which mandates a European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDI-Wallet). This is a nationally provided mobile application with which each EU citizen can identify themselves at every public institution in the EU, as well as at private parties which rely on unique identification for the provision of their services.

European Commission art. 12b, 2021

To assess the potential cross-border usage for public services, different proxies can be used. According to Eurostat, in 2019, less than 4% of EU citizens of working age were residents of another EU Member State than where they hold their citizenship. In principle, they should be able to use one eID to access public services in both Member States. In addition, there are online public services where user authentication is needed and that can be used by e.g., tourists (about 30% of EU population travel yearly to another Member State) such as buying tickets for public transport, museums or subscribing to bike rentals.

To assess the overall potential of eID use, we can rely on existing use as proxies. Available data from some Member States (e.g., NO, SE, EE, LV, LT), where user authentication solutions are widely re-used by different service providers, authenticating oneself with a legal identity is done roughly around 20 times per month, of which 1 occurs in the public sector. If that relationship is extrapolated to the EU level, we can assume the potential for EU to be roughly 100 billion user authentications per year of which 5 billion in the public sector. Based on these assumptions, for example, if we expect 3% of people living in another Member State to only use eIDAS in the current scope, the potential of eIDAS authentications in this case would be 150 million per year.

Regarding the articulation of relationships between eIDAS and private sector service providers, these are expected to remain suboptimal. Even if all notifying Member States potentially open their eIDAS nodes to the private sector services providers across the Union, the diversity of national conditions for the use of the national eID infrastructures will still make it very difficult for the service providers to build a sustainable business plan or to accurately estimate the potential of this openness to expand their business cross-border. Besides, private sector service providers have made available cross-border usage of eIDs and digital signatures through gateways like Signicat, Dokobit, TrustLynx amongst many other companies. Moreover, given the difficulty raised by the constraint to harmonize the various approaches followed at national level, a revenues model and establishing clear liability rules would be difficult to construct.

2.3.1 Processes and best practices for identity and record matching in EU/EEA countries

After the desk research of identity matching best practices in EEA countries,

Interviews revealed three main phases of the identity and record matching process which are used to structure the interview summaries (below) of the referred five countries. Those three phases are: providing identity; identity matching; and data sharing and record matching.

Those phases were refined during further analysis and merged process (see Ch.2.3.3) is described also by three-part, but somewhat different division (identity matching; e-service usage; and record matching). However, high level process descriptions of interviewed countries consist of five steps for providing more details.

Germany (DE, not interviewed)

The German eID is based on government-issued chip cards (eID cards) using certified chips and strong cryptographic protocols. The following types of eID cards are currently part of the scheme:

- German identity cards (Personalausweis) issued to German nationals living in Germany or abroad,

- German resident permits (Aufenthaltstitel) issued to non-EU nationals living in Germany, and

- German eID card for Union citizens (Unionsbürgerkarte) issued to citizens of the European Union and nationals of the European Economic Area.German_eID_Whitepaper

Due to the nature of the German eID system that operates without a central component, the German eID scheme is integrated into the eIDAS Interoperability Framework via the middleware integration model in accordance with the eIDAS technical specifications.

German_eID_Whitepaper

Public-sector bodies of other Member States of the European Union are authorized to request person identification data from the German eID of a user. For this purpose, Germany will provide an authorization certificate to each Member State free of charge. Identification and the initial registration at a commissioned authorization CA will be performed via the Point of Single Contact according to a dedicated procedure. After initial registration, the German eIDAS middleware automatically updates the authorization certificates. Provisioning of authorization certificates also includes the necessary eID revocation lists.

German_eID_Whitepaper

Poland (PL, not interviewed)

Currently there is no specific solution in place in Poland to enable universal cross-border identity matching.

For foreigners who live in the Poland there is a possibility to apply for a Polish identifier (a PESEL number regulated by the Act of 24 September 2010 on the Population Register) and one of the national notified eID means – trusted profile (pl. profil zaufany). Having a PESEL number and a trusted profile opens access to all Polish public digital services. Moreover, Poland allows access to certain public digital services for holders of notified eID means from other Member States through the biznes.gov.pl domain.

Malta (MT, not interviewed)

Identity Malta Agency, being Malta’s identity management national authority has successfully pre-notified the Maltese scheme of the Maltese eID card and e-Residence documents and has been confirmed as achieving level of assurance “high” in line with the e-IDAS Regulation. In Malta the e-IDAS Node permits Maltese citizens to use digital public services of other EU MS and gives European citizens access to the digital services of the Maltese government. It provides for a reliable authentication mechanism and allows for the mutual recognition of national electronic identification schemes. The technical infrastructure is operated by MITA, being the public entity vested with the responsibility to provide ICT infrastructures, systems, and services to the Government of Malta.

Spain (ES, interviewed)

The Spanish national identity card, known as the Documento Nacional de Identidad (DNI) or carnet de identidad, contains the following information:

- Last names (all Spanish citizens are required to have two last names)

- First name

- Gender

- Nationality

- Date of birth

- Serial number, which includes a security feature, expiry date, and signature of the cardholder

- Photo of the cardholder, in black and white and a bigger size than all the previous cards

- DNI number and security letter under the photograph

The Spanish ID card has evolved over time, and the current version is an electronic identity card with unique features.

Providing identifier

The DNI is issued by the National Police and is mandatory for Spanish citizens (fourteen years or older). The same identity number (identifier) is also used for tax purposes, receiving the name of Número de identificación fiscal (NIF)

- For individuals: The NIF for individuals is the same code as their identity document. For Spanish citizens, it will be the DNI (Documento Nacional de Identidad), which consists of 8 digits and one letter for security. The letter is found by taking all 8 digits as a number and dividing it by 23. The remainder of this digit, which is between 0 and 22, gives the letter used for security. The letters I, Ñ, O, U are not used. The letters I and O are omitted to avoid confusion with the numbers 0 and 1, while the Ñ is absent to avoid confusion with the letter N.

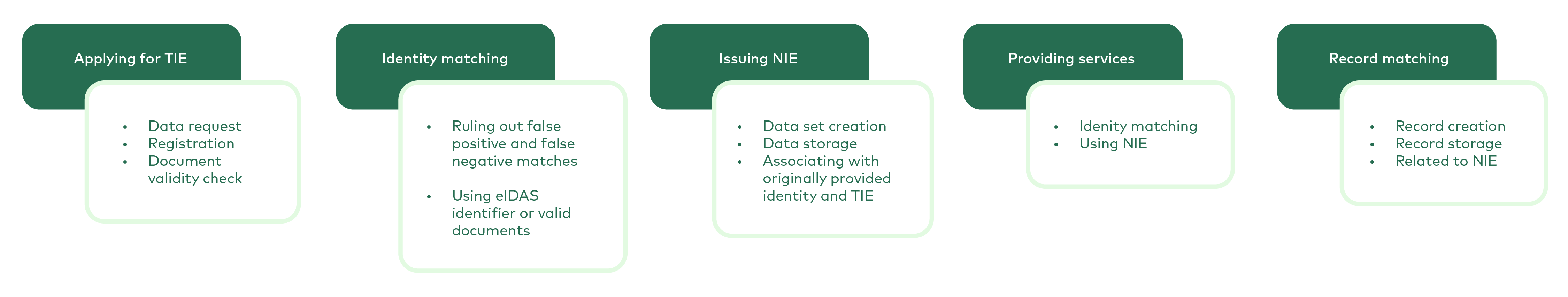

- For foreigners residing in Spain, the NIF will be the NIE (Número de Identificación de Extranjero), which is 9 characters in the format A-NNNNNNNA, where the first character is either X, Y or Z and the last character is a checksum letter.

- For legal entities: The NIF format for legal entities consists of a letter that will depend on the legal form it has, 7 digits, and the control code that can be a letter or a number.

Foreigners legally residing in Spain or who intend to purchase property are issued with a Número de Identificación de extranjero (NIE) or Foreign Identification Number

- If they are nationals of other Member States, they use their own national identity card to prove their personal identity (e.g., a French CIE) but they use their NIE as identifier for any relationship in Spain.

- If they are nationals of third countries, they get issued a Tarjeta de Identidad de Extranjero (TIE) or Foreigner Identity Card,

containing the NIE identifier, which they use to prove their personal identity. The NIE is also used for tax purposes.

The Foreigner Identity Card (TIE) which is issued to foreigners authorized to stay in Spain for more than six months

Full list of services is available in the Annex II of SDGR: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/TodayOJ/

- The card contains the individual's information, name, surname, period of validity, and a unique number known as the Foreigner Identity Number (NIE)

- The NIE is a personal unique number given to every foreigner who intends to stay in Spain longer than six months and appears on all documents of the foreigner processed and issued in Spain, including the Foreigner Identity Card

- The identity and record matching system in Spain is done to increase the success rate of identity and record matching done on the side of the Online Procedure Portal

There are several digital options available in Spain for applying for a personal ID or using public services:

- Spanish Digital ID: Spanish citizens and non-Spanish legal residents can apply for a digital ID online, register with the system using a DNIe or previously installed FNMT (Fábrica Nacional de Moneda y Timbre) digital certificate, or apply for a digital certificate from the National Currency and Stamp Manufacturer (Fábrica Nacional de Moneda y Timbre)

- Digital Certificate: A digital certificate is needed to verify a person’s identity online and formalize any legal process effectively. It can be obtained by any Spanish or foreign citizen over 18 years old who holds a DNI, NIE, or NIF, from the Sede Electrónica website. The certificate can be used to sign and prove identity safely online and allows the holder to do online procedures with the Spanish Public Administration, such as paying taxes, applying for certificates from the Civil Registry, or applying for the Spanish Criminal Record Certificate.

It is also needed not only to register as self-employed (Autónomo), but also to register documents when person is applying for TIE, making tax declarations, and joining the Social Security system, among other things

Identity matching

To obtain a digital certificate, an applicant needs to fill in personal information such as NIE, first surname, and email address. The process may require video identification and may cost a fee.

Not all municipalities are digitally approachable for using services. That depends on the size of municipality and the regional governments support to the digital services.

- In smaller municipalities (up to approximately 50 000 inhabitants) mostly or only data sharing “on paper” is in use.

- Larger municipalities (starting from approximately 50 000 inhabitants) also provide digital services for persons who have national identity (personal code and digital certificates).

For several years there has been an active push from the government to use electronic id. E.g., regarding taxes and any introduction to public services eID is a main key in terms of public services (see Figure 2).

- The TIE application process requires the submission of various documents, including proof of identity and capacity, and foreign documents must be legalized or apostilled and, where applicable, must be submitted together with an official translation into Spanish

- The student must apply for a Foreigner Identity Card within a period of one month from their entry into Spain, at the Foreign Nationals' Office or the Police.

Figure 2 High level process of Identity and record matching in Spain

Data sharing and record matching

Already identified users (with valid TIE) can connect either by national or eIDAS identifier. When connecting digitally, a respective choice will be presented to the person to use national or eIDAS identifier.

- Today it is possible to recognize EU Member States identifier as well as save it and use it for identity.

- Earlier data about the past of a foreigner cannot be matched.

- If a person is from the EU, then eIDAS identifier can be used for identity matching.

- France and Portugal create the most of identity matching cases. Both citizens can use their national electronical ID

- If a person is not for the EU, then a PIN based account can be made.

National ID has to the be Spanish identifier for most local services, but there are some sectoral exceptions and issues regarding (see Table 5):

- services meant only for residents: to use those one must have Spanish national ID. For the rest of the services also other countries national ID can be presented.

- banking: privacy focused now, so when person is asking credit from bank in Spain, then only identity is not enough, but person can decide, what data to present. Still the bank can refuse to serve if the data are not enough.

- education: When person needs to get in contract with university the problem raises when there is need to provide current degree from abroad – the documentation must be translated to Spanish and proofed by certified authority. Older diplomas from years ago are not digitized. In EU degrees from resent years are in digital database and most EU universities can share their records (degrees). (see Ch 2.2.1).

- Matching issues remain in regards of name changes or with people from third countries. For those people a new sectoral identity must be created, and data connection made to an earlier degree.

- No automatic connection between a person’ s new and former sectoral ID-s are made.

Table 5 Spain – identity and record matching related issues

Regarding | Description of the issue | Solved how? | IF not 100% solved, then why? |

Process | Smaller municipalities are not providing digital services | Government policy and nudging towards digital services | Depends on decision and available funds of every municipality |

Subject | Sectoral ID-s are causing multiple identities | Manual connections are made between data and identities | - |

Object | eIDAS – number of credentials is too limited for the Spanish national ID | Creating national Identifier for the person (duplicated identity) | - |

Regulation | eIDAS data set limits set by regulation | - | Not under control of single Member State |

Relying Parties | - | - | - |

Technology | - | - | - |

Infrastructure | - | - | - |

EU | - | - | - |

Compiled according to the interview with the representative of University of Murcia (expert of security and identity related topics)

Summary of differences in the process of obtaining a digital certificate for foreigners (for use in Spain):

- Foreigners need to obtain a Foreigner's Identity Number (NIE) before applying for a digital certificate. The NIE is a unique identification number assigned to foreigners in Spain, and it is required for all financial and administrative matters.

- Foreigners can apply for a digital certificate online through the Sede Electrónica website, just like Spanish citizens. However, the application process may require additional documentation, such as a copy of the applicant's passport and a copy of their NIE.

- Foreigners may need to provide proof of their legal status in Spain, such as a residency certificate or a work permit, to obtain a digital certificate.

- The process of video identification may be different for foreigners, depending on their legal status in Spain. For example, non-residents may need to provide additional documentation to complete the video identification process.

- To summarise, while the process of obtaining a digital certificate is similar for Spanish citizens and foreigners, foreigners may need to provide additional documentation and proof of their legal status in Spain.

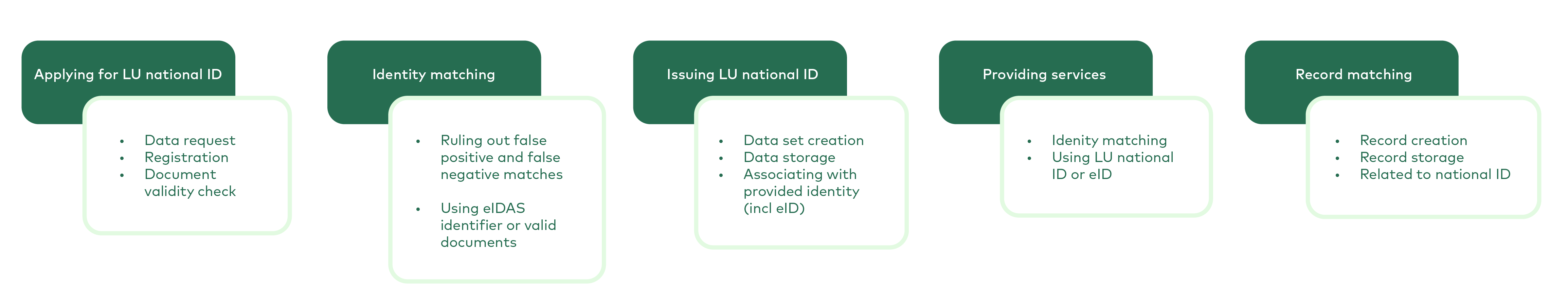

Luxembourg (LU, interviewed)

In Luxembourg, identity matching of citizens relies on a persistent national identification number, as foreseen by the law of 19th June 2013 on identification of natural persons.

Providing identifier

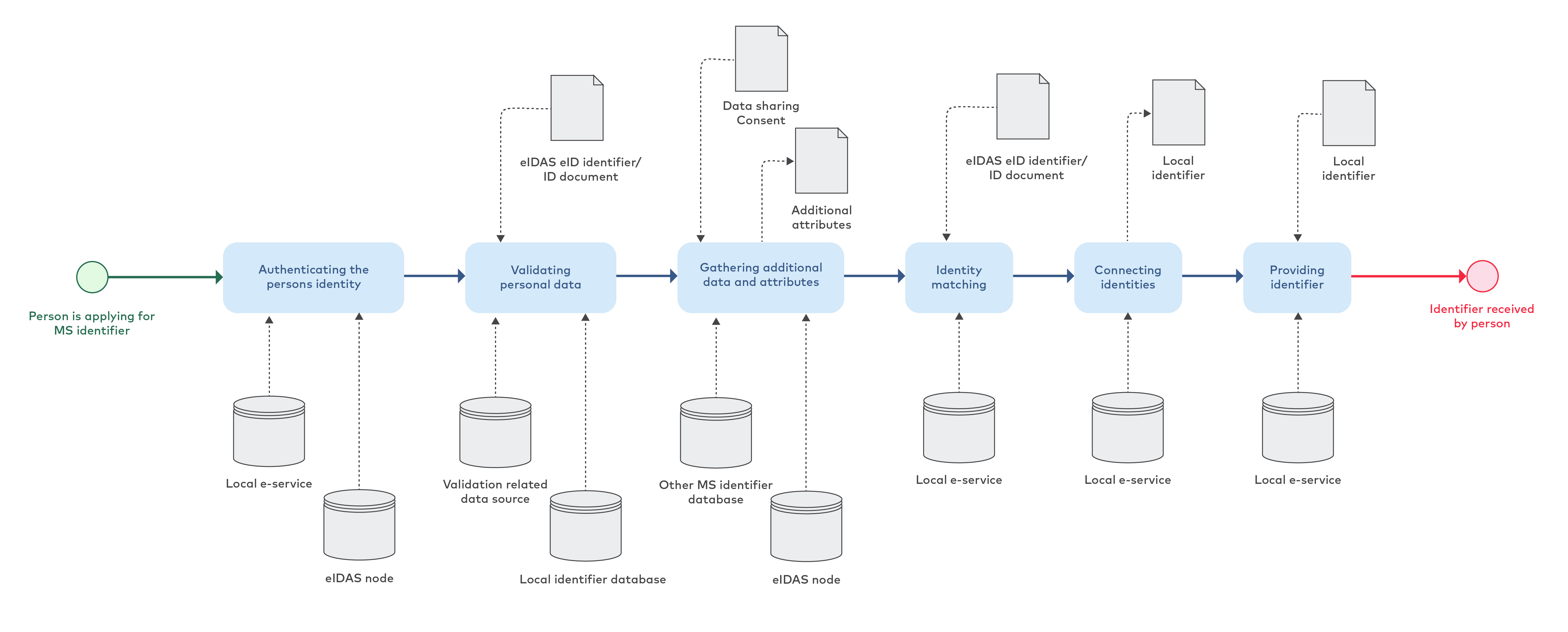

Foreign citizens can obtain a LU national identification number via various registration processes, including fully online if they own an eID means notified under eIDAS. When a person from abroad requests for LU national ID, an eIDAS identification is used today. To support the process, the original minimum dataset required for LU national ID was changed, as previously gender was asked, but e.g., Germany doesn’t provide this attribute. That means using only eIDAS minimum dataset today (see Table 6).

The Luxembourg national identification number has a different format for natural and non-natural persons.

- For non-natural persons, the identifier has 11 digits, and the last digit is a check digit.

- For natural persons the national identification number for natural persons has 13 digits

. The digits in the national identification number represent the following data: - RRRRRR: Birth date of the person in the format YYMMDD

- SSS: Serial number assigned by the National Registry of Natural Persons

- C: Check digit

To evidence the information required for the creation of the national identification number, the natural person should provide the following information: names, surname, date, place, and country of birth, gender, nationality, and private address.

Table 6 Luxembourg – identity and record matching related issues

Regarding | Description of the issue | Solved how? | not solved why? |

Process | Sector specific approach to datasets and sharing principals | Some data are shared “on paper”, which means not shared digitally. | No standardized approach agreed in state, sector specific processes |

Subject | Citizen from abroad can have multiple eID’s from same country or different country. | Manually associating the various eIDs with a single LU identity (i.e., the one in LU national population register). National population register calling the person, requesting documents, checking, and then merging data. | - |

Object | Legislation prohibits to share national ID number with parties abroad | Derived unique identifier based on LU national ID number, created by algorithm, by country and by relying party. The same code is used also in the future and tied: unique person eID = requesting country + requesting organization | National regulations |

Regulation | ID number cannot be saved by private sector (with some exception, e.g., healthcare) | Person can choose what to share by giving an official consent | National regulations |

Relying Parties | Largely sector specific processes | - | Every sector and organization are deciding their solution. Private sector cannot store national ID number, with a few exceptions which are all enumerated in a national law |

Technology | - | - | - |

Infrastructure | - | - | - |

EU | Pinpointing false positive or negative matching cases | - | eIDAS minimum dataset |

Identity matching

Matching and providing of services is based on national identifier – 1 identifier per natural person. When asking for service, one must provide the national ID, which is a primary key to access all the information in various databases.

- Person can apply for national ID via web page

by providing minimal set of data. If additional data is required, the consent will be asked, and applicant can decide whether to share more data or not. All additional checks (points 1,2,3 below) are done separately and manually by agents of the National Population Register service, outside of the online eIDAS-based registration. - Identity document and facial biometry matching,

describes how the document should look like), the same information about ID documents from outside EU is also available. - Electronic security – chip with signed data from member state, mobile app is used for that.

- Question of document validity – many public sector institutions have no access to the SLTD database to check is this document stolen for example? In case of doubt the authorities of issuing MS will be contacted.

- Business owner is connected to the company, that must be registered in Luxembourg. EU network business register BRIS

links all the business registers data from all MS’s.

Figure 3 High level process of Identity and record matching in Luxembourg

Data sharing and record matching

Every person with LU national ID can have a personal digital space provided by LU on the national citizen portal (MyGuichet.lu)– where the person can use different services. This service is available to everyone with a national identifier, but a person must request its creation. There are some issues (Table 6):

- Citizens can have multiple eID from the same country or different countries, as well as different names for some cases. Unique identifiers provided by various eID means of single person are not matching, so different identities must be manually associated. For this association the National Population Register will call the person, requesting documents, checking, and then merging data.

- Private and public sector service providers options are quite different.

- In the public sector all sector-specific processes rely on the national identification number. And public administrations supporting these processes have access to the central national population register.

- But national ID numbers cannot be stored by the private sector, therefore they must use another way to identify the person.

- On education field depends on University, but mainly the data should be provided “on paper”. Some Universities in certain networks can exchange data directly.

- Medical sector – patient history from abroad is shared mainly “on paper.”

- Financial sector - some banks are online, some have digitalized part of their bank account opening process, some are still operating with data sharing “on paper”.

When interacting with LU public entities, citizens provide their identification number for identity matching. Alternatively, they may use their notified eID means and authenticate via eIDAS, since their eID means has been associated with their national identification number during registration.

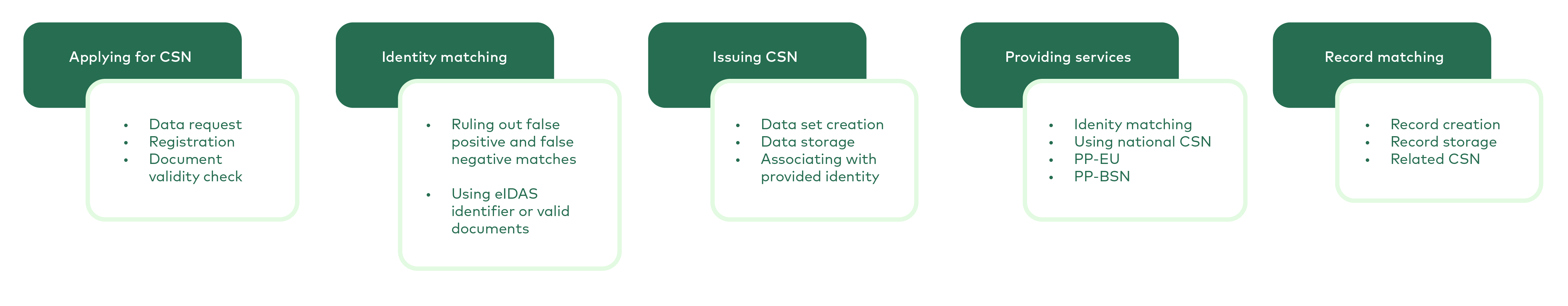

Netherlands (NL, interviewed)

In the Netherlands, online unique identification in the public sector is often established by comparing a citizen’s Citizen Service Number (CSN) to a record of that citizen at a public RP

Relying Parties

Providing identifier

Dutch CSN is a unique number of 9 digits, including check digit; that contains no personal data.

Besides the CSN, the following four unique and persistent identifiers are used in the Dutch eIDAS identity matching process of foreign eID means (Nora, 2017; Verheul, 2019).

- eIDAS identifier: the identifier which is used in the eIDAS minimum data set (PID). For each MS, the identifier is formatted as: [home_MS/destination_MS/ID (e.g., GE/NL/1234AB)

- PP-EU: a polymorphic pseudonym which is derived from the eIDAS identifier. This identifier is used for Dutch RPs in the private sector.

- PP-BSN: a polymorphic pseudonym which is derived from the BSN. Every eID mean a citizen uses receives a different PP-BSN. The BSN is only derivable from the PPBSN by Dutch RPs which have a decryption key. This key is only given to authorized RPs.

- PP-RP: a pseudonym specifically for each Dutch RPs. It is a pseudonym of the former two identifiers (the PP-EU, PP-BSN), constructed by encrypting this identifier with the public key of the RP. Therefore, only the authorized Dutch RP can derive the decrypted identifier. A RP does not have access to the PP-EU, PP-BSN, and PP-PS: they are only for internal communication between the Dutch eIDAS Connector and the BSN Connector.

Identity matching

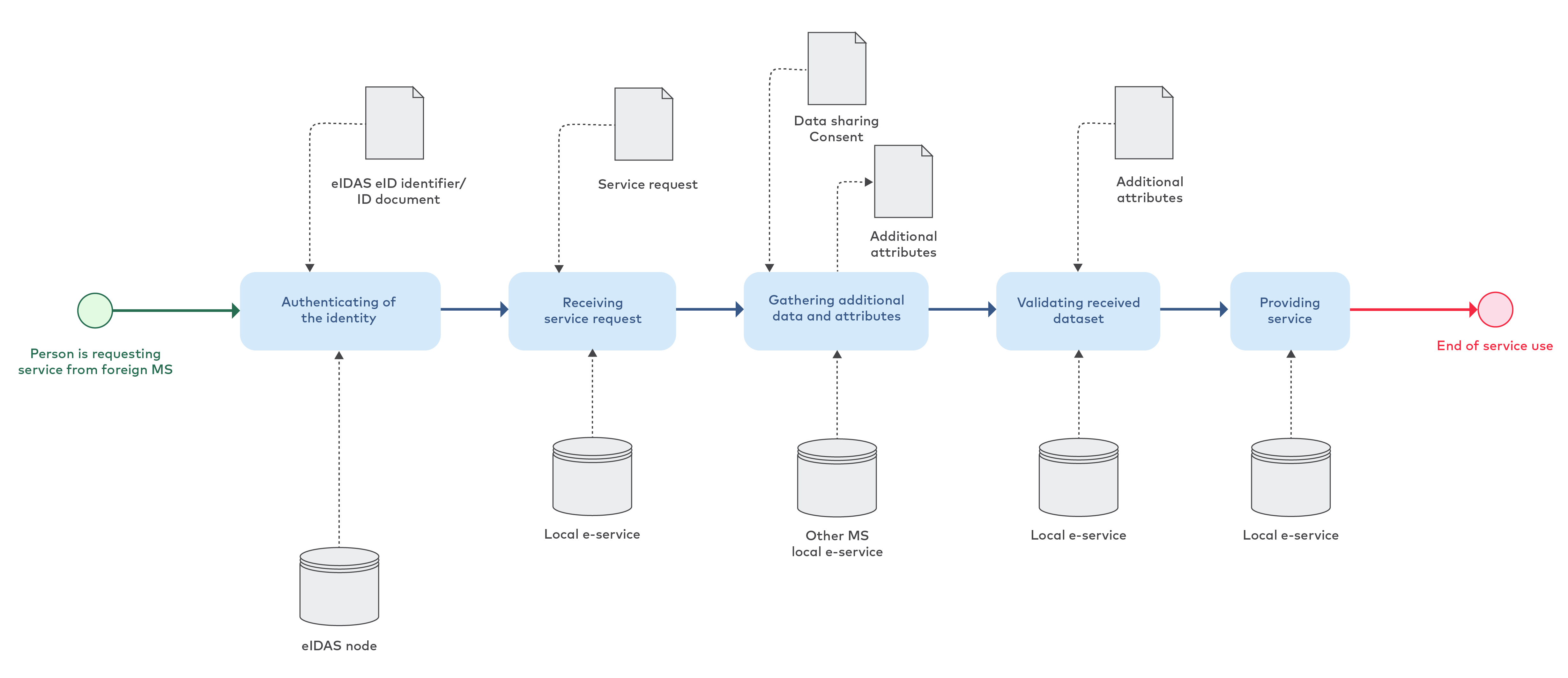

Focus on identity matching is to avoid false positive matches first and only after those false negative ones. Matching is done starting with surname and date of birth (age). In case of one positive match, additional ID document data are asked, if these are not shared then last 3 digits of CSN is provided and confirmation is asked from the person. If more than one match is found in the database, then the matching is forwarded immediately to the manual process (back office). More attributes will be asked from the country of origin and the person must give consent for that. If still in doubt, then identity match won’t be done to avoid false positive and possible frauds caused by it. (see Figure 4)

Figure 4 High level process of Identity and record matching in Netherlands

Matching itself is not a problem, the data are – e.g., people already with multiple identities in other countries and in addition there are problems with old identity documents. The more identity related data is gathered through time, the better the matching will be.

A person with no eID code must come to the physical location and present ID (paper documents, ID card) Local ID document is linked to the name, date of birth, gender, nationality, and home address. For people from abroad the main identity matching attributes are birth date and family name. In case of doubt the data of parents are requested, but sharing these is not obligatory. Still, when refused to share this information, and if it leaves doubt of person’s original identity (from abroad), this can end up with refusal to provide CSN. (see the list of issues at Table 7)

It is possible to connect identities manually. This option was created because of 2 main reasons:

- Differences in spelling of names in different languages (e.g., prefix De’: In Netherland it is separated, in Belgium it is concatenated into one name)

- Very common names witch even together with birth date can give more than 1 positive hits from database. (e.g., German surname with a very common name in Netherlands can give up to 10 hits with the same birth date).

On the other hand, it creates another problem, where connections could be made recklessly. To prevent that from happening the procedure allows only 2 people to connect identities, and related logs are stored.

Data sharing and record matching

In the Netherlands, all public organizations working with personal data use the Citizen’s Service Number to identify people and to communicate between public organizations. Without this CSN it is not possible to access most of the public services of more than 1000 government institutions.

Table 7 Netherlands – identity and record matching related issues

Regarding | Description of the issue | Solved how? | If not 100% solved, then why? |

Process | Person who doesn’t have CSN code, must come to the office and present data | From abroad people can connect via eIDAS and can use eIDAS identifier. | Still physical presence is required for identity matching |

Subject | False negative matches can happen because of the spelling differences between languages | The name details (letter combinations like name prefixes etc.) are coded to match language specific changes in the surname | Focus is on avoiding false positive matches. |

Object | More than one positive hits from database | In case of 2 positive hits person is asked to confirm last 3 digits of CSN (yes/no) Manual connection of identities is possible | If still in doubt, then the connection of identities will not be done (to avoid false positive and possible frauds) |

Regulation | In case of doubt in >1 positive hits legislation prevents from demanding additional data. Either new identity should be provided, or identity connection made. | Person is asked to share data voluntarily | Person can refuse sharing additional data and public services must be provided still but under new identity |

Relying Parties | Most public service providers have their own systems established | One central database with all the persons, accessible to all service providers | - |

Technology | - | - | - |

Infrastructure | - | - | - |

EU | - | - | - |

Compiled according to the interview with the representative of the National Office for Identity Data (Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations)

Incoming eIDAS-traffic comes with a Unique ID and attributes (name, surname, date of birth). Service will be provided if the attributes can be matched to a registered identity.

Norway (NO, interviewed)

Providing identifier

The identification process requirements when applying for identification documents depends on an individual's citizenship and the basis for their residence permit in Norway

- Nordic citizen: Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Finland, Denmark, the Faroe Islands or Greenland

- Passport or national ID card with a photograph of the person and information about the person’s citizenship and gender is required. When moving to Norway from another Nordic country, a valid driving license will also be accepted, together with a printout from the national population register of the country one is moving from, with information about citizenship and gender. The printout must be dated and no older than three months. It must also be signed and stamped.

- Children under the age of 18 may use their birth certificate/printed confirmation of their birth registration from the National Population Register in a Nordic country together with a passport photo and a printout from their home country’s national population register that shows their citizenship and gender. The printout must be no older than three months. It must also be signed and stamped.

- EU/EEA/EFTA citizens: Passport or national ID card with a photograph and information about citizenship and gender.

- There are some exemptions for some groups, like asylum seekers, refugees, persons who are unable to get a passport from their home country, and others.

The Anti-Money Laundering (AML) legislation requires that customers provide valid proof of identity when entering a customer relationship. Valid proof of identity includes Norwegian and foreign passports, Norwegian national ID cards, Norwegian driving licenses, Norwegian bank cards with photographs, national ID cards issued by an EEA country, Norwegian immigrant's passport, Norwegian refugee travel document, and electronic proof of identity in accordance with the AML Regulations.

For permanent ID any person should have a permit for residency – this can be acquired by presenting a passport (ID document).

- To apply for work, permit also sending documents is accepted today, but the quality of this method is questionable and will most probably be discontinued. Physically appearing to receive the work permit the office.

- Enrolment for ID cannot be done digitally today. It is under decision whether to issue national identity card for foreigners, but still, physical appearance is required to receive the ID document.

All together three kinds of identifiers can be defined regarding Norway:

- Personal unique identifier, restricted by population register legislation, prevents changes of attributes, as every change requires change in the legislation.

- Internal identifier – sectoral numbers (like in taxation or health care)

- Third identifier is under consideration – which would be more flexible in regards of Norway legislation and would allow additional attributes and change of some data (like address and similar).

A national identity number consists of eleven digits

- Date of birth: In most cases, the date of birth is the first six digits. For example, if person is born on 22 June 1976, the first six digits in your national identity number are 220676.

- Individual number: The next three digits are individual numbers, where the third digit refers to the holder’s gender: even numbers for women and odd numbers for men.

- Verification number: The two last digits are for verification.

- The last five digits in the national identity number can be referred to as a “personal number”.

- In some cases, the first six digits are not the date of birth – in case there are no available national identity numbers for some dates. Then, the first six digits will show the day and month on which person received your national identity number instead. The correct date of birth will still be recorded in the National Population Register in the field for date of birth.

Changing information regarding one’s identity is possible: person can apply to change their registered information regarding place of birth, country of birth, citizenship, and date of birth through the Norwegian Tax Administration.

Identity matching

All foreigners working onshore in Norway are required to meet at a tax office for an ID control to verify their identity.

Data sharing “on paper” is only under discussion if a person cannot be identified with regular processes. Norway focuses first on avoiding frauds with multiple identities – so priority is to avoid false negative matches and right after those false positives. (see also Figure 5)

The status of person’s identity basis can be either checked or not checked

Figure 5 High level process of Identity and record matching in Norway

Biometric data are considered sensitive and not used for eID. It is considered using web apps for digital biometric enrolment, but not explored much so far. Central passports register stores photos and fingerprints, and these data can be checked, to make sure that no duplicate identities are created. However, double identities cannot be completely ruled out since one-to-many queries are not allowed with biometrics. Biometrics can only be used for a 1:1 comparison, to make sure that the person is who he/she claims to be. This process is under the control of the police. Current legislation does not comply with the identity matching solutions connected to biometric data. Uniqueness and quality of personal identity decreases, therefore. (see the list of issues at Table 8)

Data sharing and record matching

The population register is very high quality, and it is very often used as a comparison for other systems, which means that national identity number is used very widely. If people from abroad cannot be connected to the registered ID number, it is not possible to use public services. There are some exceptions – e.g., applying to university or paying taxes, for that internal identifiers are used. Health care also handles foreign patients – who don’t get Norwegian identifiers, and very limited range of digital services are accessible for them. In corona pandemic situation those internal identifiers were temporarily used as a person’s identifier in Norway, but this system was not extended.

Table 8 Norway – identity and record matching related issues

Regarding | Description of the issue | Solved how? | If not 100% solved, then why? |

Subject | If persons from abroad cannot be connected to the registered ID number, it is not possible to use public services. | Sectoral internal identifiers are used. In corona pandemic situation those internal identifiers were temporarily used as a person’s identifier in Norway, but this system was not extended. | There are some exceptions – e.g., applying to university, paying taxes or receiving critical health care. |

Object | People have a long history and rights for services (like pensions). They come with a minimum data set from abroad or with a passport. And data quality differs a lot therefore. | A person is asked to share additional data and documents to find a match. Status of identity check is available to public and private enterprises that use the National Population Register. | Inflexibility in population register and rigorous government systems connected to that register. |

Regulation | Personal unique identifier related regulation prevents changes of attributes | Third identifier is under consideration – which would be more flexible in regards of Norway legislation and would allow additional attributes and change of some data. | Restricted by Population Register legislation and therefore every change requires change in the legislation. |

Relying Parties | Data is not shared between countries flexibly. | Physically appearing to present data and or receive work permit or ID document. | Variations of legislation of population registers in different countries. |

Technology | - | - | - |

Infrastructure | - | - | - |

Cultural | People are not ready to consider possibility to use EU unified identifiers. | - | - |

EU | In some cases, it is not possible to find a user in the eIDAS register, even if the person is registered. | - | eIDAS mandates sharing information but does not mandate access to services. |

Compiled according to the interview with the representative of The Directorate of Digitalisation

Estonia (EE, interviewed)

Estonia has personal identification code and ID documents as many other countries, that allow foreigners to deal with their personal or business matters.

Providing identifier

All Estonians, no matter where they happen to reside, have a state-issued digital identity. This electronic identity system, called eID, has existed since year 2002 and is the cornerstone of the country’s e-state. e-ID and the ecosystem around it is part of any citizen’s daily transactions in the public and private sectors. All Estonian eID tools operate primarily on the Estonian personal identification code for identification. People use their e-IDs to pay bills, vote online, sign contracts, shop, access their health information, and much more.

ID-card is mandatory for every Estonian citizen and residence card is mandatory for all residents living in Estonia. Estonians can use their e-ID via state-issued ID-card, using Mobile-ID, which can be used on any mobile device with SMS functionality, or Smart ID app on their smartphones. Holders of a digital identity need not be Estonian residents anymore, however.

Since 2014, an e-residency of Estonia (also called virtual residency or E-residency) concept was implemented for anyone who wishes to become an e-resident of Estonia and access its diverse digital services, regardless of citizenship or location. Behind that is an aim to make it easier for foreigners to access Estonian business environment remotely and thereby attract location-independent entrepreneurs such as software developers.

E-Residency of Estonia is a program that enables creating a borderless digital society for global citizens. The program provides holders of e-Residency with a transnational digital identity (e-Resident’s digital ID) that allows to securely authenticate non-Estonians in Estonian online services, such as company formation, banking, payment processing, and taxation and sign documents.

A personal identification code is a number formed based on the gender and date of birth of a person which allows the specific identification of the person.

- the EVS 585:2007 standard “Personal identification code. Structure”

- the Population Register Act