1. Introduction

The rapid growth in the production and use of plastic products in the past few decades has emerged as a pressing issue of global concern, posing multifaceted challenges to human health and the environment, and slowing the achievement of a sustainable circular economy. The most problematic, unnecessary and avoidable (PUA) of these products often come in the form of single-use plastics, such as carrier bags, straws, disposable cutlery, and packaging materials. These represent approximately 36% of plastic production, of which an estimated 85% is mismanaged (UNEP, 2023a).

Single-use plastic products have repeatedly accounted for the majority of product categories in the top ten items found in coastal areas (ICC, 2020), with cigarette butts being the most common item. Microplastics from tyre and road wear are major contributors to plastic pollution (Järlskog et al., 2020), while emissions of microplastics and chemicals of concern from artificial turf and crumb rubber infill have warranted attention by policymakers (Zuccaro et al., 2022).

However, the plastic pollution problem extends well beyond single-use applications. For the upcoming global agreement to end plastic pollution, there is a need to develop global criteria for determining single-use plastics, as well as other applications and categories of products which can be considered problematic, unnecessary or avoidable. The criteria can be used to regulate current and future plastic products at the global and national level.

1.1 Objective and scope of the report

The goal of this report is to contribute to the development of control measures for PUA plastic products under the international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment (hereafter: plastics instrument), by adding to the following:

- Strengthening the understanding of the characteristics of PUA plastic products.

- Provide potential criteria for determination of PUA plastic products.

- Provide potential governance approaches needed to control PUA plastic products.

The aim of determining problematic, unnecessary and avoidable plastic products is to establish appropriate measures at the global and national levels to, e.g.:

- remove them from the market,

or - reduce their production by promoting alternate practices or non-plastic substitutes,

and - redesign problematic products to be safe and functional for intended uses, and according to criteria for sustainable and safe product design.

In support of these goals, the report also addresses:

- The linkages with other potential control measures of the plastics instrument as they relate to the global regulation of PUA products, such as the regulation of chemicals and polymers of concern and sustainable and safe design.

- The role of a potential scientific mechanism under the plastics instrument to support the governance of PUA products.

The focus of the report is all plastic products placed on the market, including consumer products. The aim is to facilitate their determination under the plastics instrument as problematic, unnecessary or avoidable, based on different sets of criteria elaborated for this purpose.

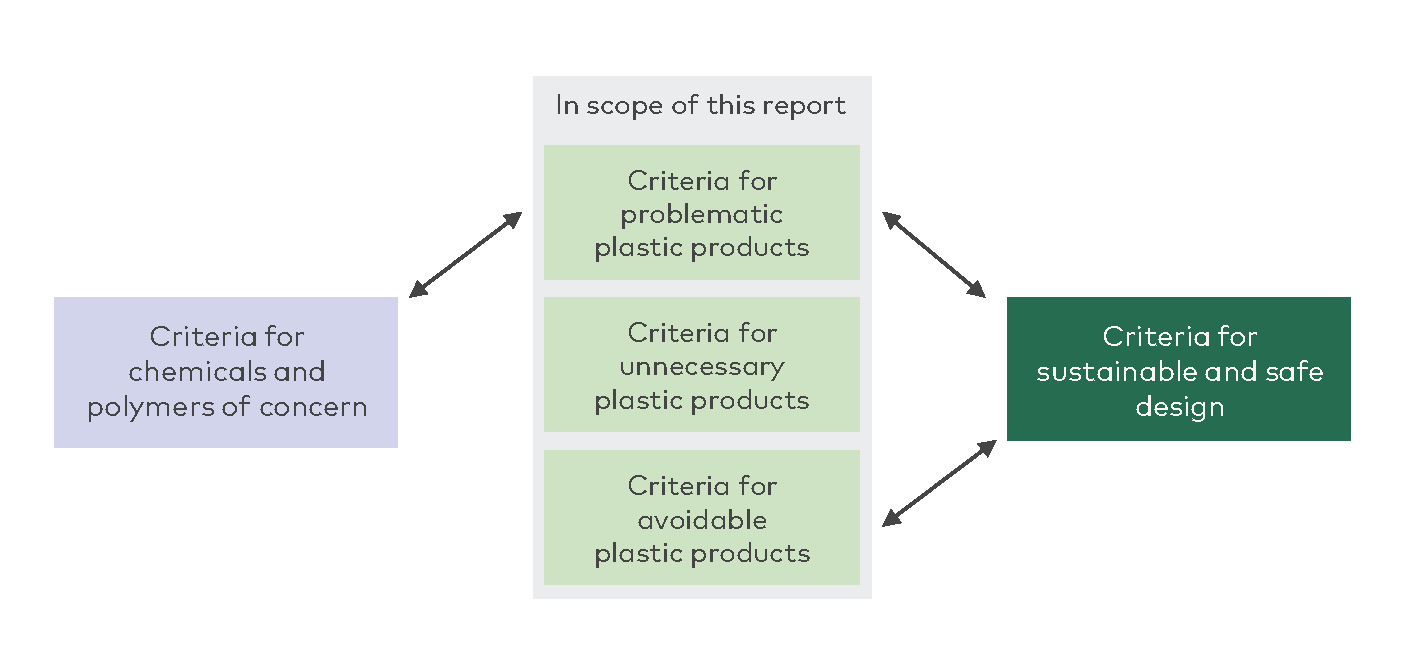

Figure 1 illustrates the scope of this report in blue, in context of the three sets of criteria proposed in the Zero Draft text (UNEP, 2023b). Criteria for identifying problematic plastic products are closely linked to potential criteria for chemicals and polymers of concern, as the latter may contribute to the determination of what is considered “problematic plastic products”. Criteria for problematic and avoidable plastic products are also closely linked to potential criteria for sustainable and safe design, as the latter may be the preferred endpoint for transitioning away from products and polymers identified as problematic and/or avoidable.

Figure 1. Interlinkages between criteria sets in the upstream phase of the plastics life cycle.

Section 1 of the report outlines the background to the topic, which is followed by a description of the methodology of the report, including the basis for the selection of criteria in section 2. Section 3 lists potential criteria for identifying PUA products, while section 4 discusses a potential process for determining and listing such products. Lastly, section 5 outlines possible institutional arrangements for listing PUA products. Box 1 provides definitions and terms used in this report.

Box 1: Definitions and terms used in this report.

- Alternate design: Variations on design of a product that provide an equivalent function and to a performance level as necessary. Such design could lead to removal of plastic or reduction of plastic use, as well as removal of problematic elements.

- Alternate practice: A modified and/or replacement business model or production system that provides an equivalent and environmentally sound function or end-use to the original product. Such practices could lead to a removal of plastic or a reduction of plastic use, as well as removal of problematic elements.

- Exceptions: Special allowances applied to specific products, usually to exclude those products from restrictions.

- Exemptions: Requests submitted by Parties to the Secretariat of the plastics instrument for an extension on the agreed timelines for phase-out or phase-down of restricted products.

- Essential use: The Montreal Protocol provides an example of the substantive criteria for essential use exemptions "Use of a controlled substance should qualify as essential only if: (i) it is necessary for health, safety or is critical for the functioning of society (encompassing cultural and intellectual aspects); and (ii) there are no available technically and economically feasible alternatives or substitutes that are acceptable from the standpoint of environment and health" (Decision IV/25, para 1a).

- Non-plastic substitutes: Materials derived from natural, non-fossil sources like plants or minerals that are not considered plastic, offering similar utility as plastics, but are safer and less harmful to the environment (adapted from UNCTAD, 2023). Such substitutes could lead to removal of plastic or reduction of plastic use, as well as removal of problematic elements.

- Oxo-degradable plastic: plastic materials that include additives which, through oxidation, lead to the fragmentation of the plastic material into micro-fragments or to chemical decomposition (EU, 2019a).

- Plastic products: Products, including packaging, made entirely of plastic, or containing plastic (UNEP, 2023a).

- Plastic polymer: Any synthetic and semisynthetic macromolecular substance obtained by polymerization of monomers, including monomers, additives and processing aids.

- Product: An identifiable physical or tangible item offered for sale and used in the manufacture of plastic products, including precursors of plastic products.

- Secondary plastics: Plastic polymers made from recycled material (OECD, 2022).

1.2 Background

In 2019, the production of plastics soared to 460 million tonnes per annum, representing a doubling from the year 2000 (OECD, 2022). At the same time, plastic waste generation more than doubled to 353 million tonnes per annum. Of this, 50% was allocated to sanitary landfills, 19% incinerated, and 9% recycled, while the remaining 22% was either dumped in unregulated sites, burned in open pits, or leaked into the environment. Without international intervention, the annual volume of mismanaged plastic could nearly double, and the production of new plastics could rise by 66% by 2040, compared to 2019 figures (NCM, 2023).

Plastics affect both terrestrial and marine species in many ways, as well as contribute to increased releases of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Plastics are also linked to health concerns, in particular due to the presence of numerous chemicals of concern (Landrigan et al., 2023). The identification and gradual removal of unsafe and unsustainable plastic items, accompanied by redesign and detoxification of indispensable products, will play a vital role in reducing plastic pollution. It will help in stemming production levels, as well as reducing waste generation and subsequent leakage to the environment and biota (UNEP, 2022).

In recent years, the issue of problematic, unnecessary and avoidable (PUA) plastic products has gained prominence, leading to the implementation of bans, restrictions and voluntary measures worldwide for a limited set of problematic plastic products and polymers.

Refer to Table 1 and Table 2, Appendix 1 and Appendix 2.

The development of the plastics instrument presents a unique opportunity to establish control measures and associated global criteria on PUA products that can harmonize national efforts in restricting their use, thereby creating a level playing field for both companies and countries. The Zero Draft refers to “problematic and avoidable plastic products, including short-lived and single-use products and intentionally added microplastics.”

Zero Draft, Part II, Control Measure 3. See paragraphs a, b.

Zero Draft, footnote 13.

Zero Draft, footnote 16.

- criteria for the determination of problematic and avoidable products or groups of products,

- a listing of specific products or groups of products determined to be problematic and avoidable, and timeframes for their phase-down or phase-out, and

- potential exceptions as needed, for example for essential uses.

A country-led informal technical dialogue, co-chaired by the United Kingdom and Brazil, developed a briefing report to inform the third meeting of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-3) on possible criteria for control measures, including for problematic plastic products (UK and Brazil, 2023). This and other stakeholder input provided momentum for informed discussions at INC-3 that are reflected in the Co-chairs’ summary of Contact Group I. The summary states that various opinions emerged regarding the Zero Draft options, with some members advocating for no change, others emphasizing exceptions for critical uses in healthcare and food, and concerns about the potential negative effects on vulnerable groups, especially in developing countries (UNEP, 2023c). Additionally, there were calls for implementation methods, criteria sets for specific products, and consideration of factors such as traditional knowledge, health, environmental impacts, and the importance of feasible, accessible, and non-harmful alternatives, tailored to national circumstances (UNEP, 2023c).

The 2020 Nordic report on possible elements of a new global agreement to prevent plastic pollution proposes controlling problematic, unnecessary and/or avoidable plastic products at the global level as a key element (NCM, 2020). Other relevant reports and initiatives include:

- WWF’s report by Eunomia identifies 17 core product groups for regulation, categorized into those in need of elimination or reduction, and those requiring safe circulation and management, based on a risk-based analysis and a feasibility study (WWF, 2023).

- The New Plastics Economy Global Commitment promotes the use of voluntary criteria for problematic and unnecessary plastic packaging or plastic packaging components among global commitment signatories in several countries (EMF, 2023).

- Annex I to the Commission proposal for a European Union (EU) Regulation setting ecodesign requirements for sustainable products and repealing Directive 2009/125/EC proposes product parameters for sustainable product regulation (European Commission, 2022a).

- A report from the Forum on Trade, Environment & the SDGs (TESS) outlines options for Trade-related cooperation on problematic and avoidable plastics building on existing experiences with single-use plastics (Sugathan & Birbeck, 2023).

- The report published by the Secretariat of the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm (BRS) conventions on global governance of plastics and associated chemicals conceptualizes a potential scope for plastic pollution, including problematic, unnecessary and avoidable plastic products to be prioritized based on selection criteria (BRS, 2023).

- A concept note from Plastics Europe proposes the use of a decision-tree assessment (instead of a negative list) consisting of a hierarchical flow of questions to help identify and address either problematic and/or avoidable plastic applications (Plastics Europe, 2023).

- The Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation (APCO) has identified criteria for problematic plastic packaging, noting that future technological advancements might reclassify some of these products (APCO, 2020).

Findings from the review of the above found the following tendencies that this report aims to supplement:

- A focus on single-use plastics and packaging.

- A scope that is mostly limited to the end-of-life issues and leakage of plastic products.

- Provision of criteria for two classifications, such as problematic and avoidable, for which the distinction was not always clear.

- Poor representation of alternative business practices.

- Criteria were not always appropriate to a wide range of country contexts, i.e. appropriately flexible for the global level.

- Application to new types of products placed on the market in the future was not a key objective.

- Promotion of alternatives and non-plastic substitutes only if they were considered economically and socially feasible. This could disincentivise the development of new solutions or the scaling of existing solutions.

The review of current suggestions for addressing problematic, unnecessary and avoidable plastic products indicates a need to develop criteria sets that cover all potential PUA products in a holistic way.

1.3 Summary of current restrictions of products, polymers and monomers

This report builds on existing products and product-specific polymers that are currently regulated. Some plastic polymers and many products that would be classified as PUA under the criteria suggested in this report have already been regulated in many countries and some at the regional level (Table 1 and Table 2).

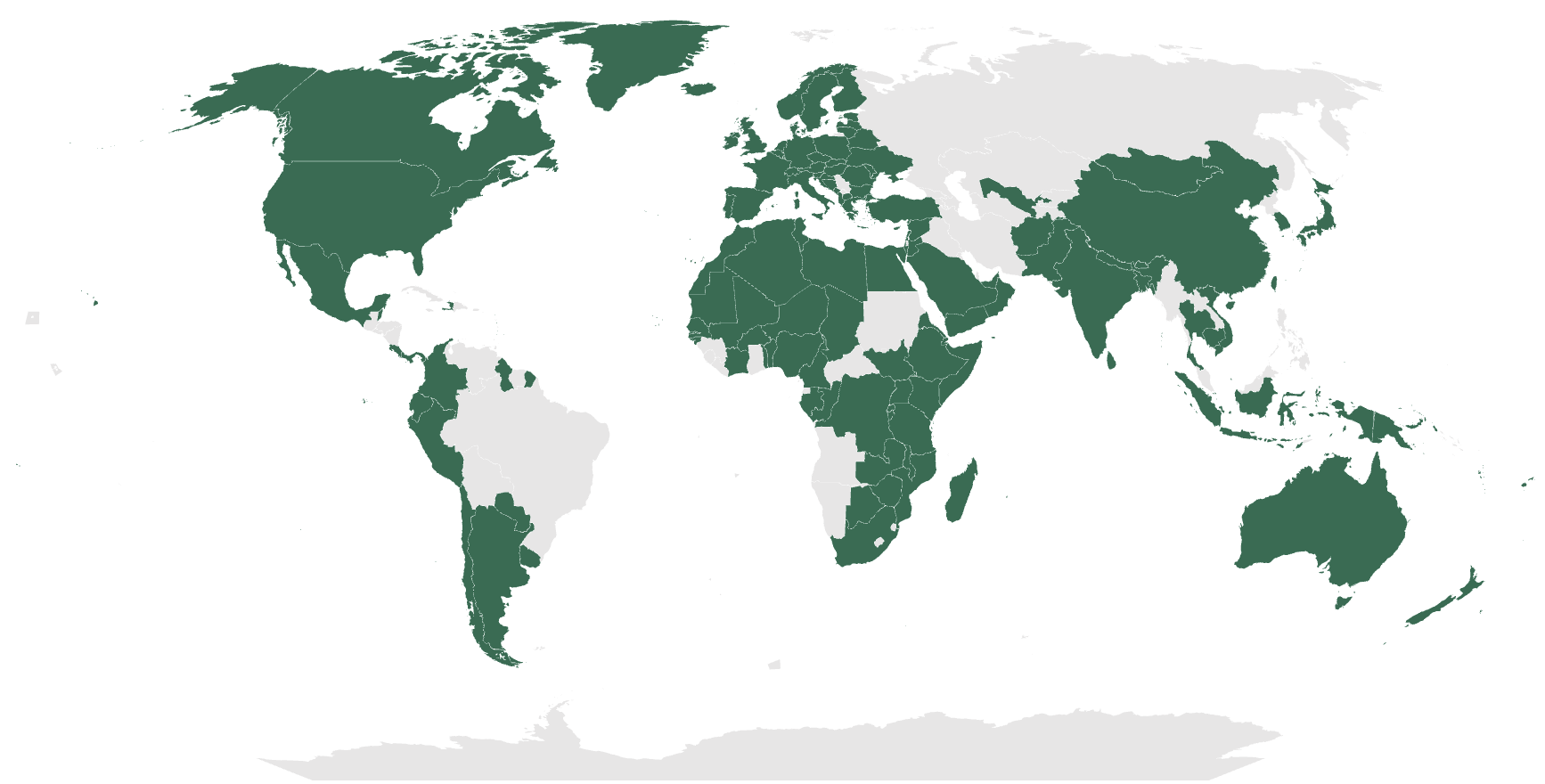

Current research indicates that a total of 141 countries have banned or restricted some form of plastic products, and 33 countries have banned or restricted one or more plastic polymers or monomers (in some cases, for particular applications only). Figure 2 illustrates the countries and regions that have regulations in place for one or more plastic products, as per current research.

Figure 2. Geographical view of countries in which at least one plastic product is banned or restricted at the national or regional level (n=141).

As shown in Table 1, a range of plastic products have been banned or restricted at the national and, in some cases, the regional level. The examples provided are summarised from existing research with further details and a full set of references are provided in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2, respectively. Notably, developing countries were early adopters in banning single-use plastic bags, with Bhutan setting a precedent in 1999 (Knoblauch, 2018). Following this, the EU took a significant step two decades later by introducing the Single-Use Plastics Directive, marking the first comprehensive effort to tackle SUPs. This move prompted a wave of similar legislation in other nations. In countries without national bans or restrictions, many states, cities and municipalities have independently implemented local bans on certain plastic products (Karasik et al., 2020). Regulatory approaches have also been complemented with voluntary interventions, including actions from citizens, non-government actors and private sector (Schnurr et al., 2018). However, despite these varied national and regional efforts, a cohesive, consistent and effective strategy to manage PUA plastic products is yet to be established.

Table 1. Plastic products banned or restricted at the national

In this summary, ‘countries’ are counted and not ‘Member States’ of the United Nations. For example, the constituent countries of the United Kingdom (England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland) are counted individually as they legislate plastic products separately.

Plastic product | Banned | Restricted |

Agricultural film | 1 Country | - |

Banners (signs) | 2 Countries | - |

Board stock | 1 Country | - |

Beverage bottles | 7 Countries & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) | 28 Countries & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) |

Boxes | 1 Country | 2 Countries |

Cotton swabs/ear buds | 8 Countries & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) | 1 Country |

Cups/glasses (and their lids) | 20 Countries& 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) | 1 Country & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) |

Cutlery/utensils (incl. forks, knives, spoons, chopsticks, stir-sticks, candy sticks, ice-cream sticks) | 21 Countries & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) | 4 Countries |

Egg cartons | 3 Countries | 1 Country |

Fishing gear | - | 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) |

Food containers (and their lids) incl. clamshells | 17 Countries & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) | 1 Country & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) |

Horticultural netting | 2 Countries | - |

Invitation cards | 1 Country | - |

Microbeads These regulations apply to microbeads only, a form of intentionally-added microplastic defined as an extremely small piece of material manufactured for various applications, especially one made of plastic and used in personal care products, cosmetics, and detergents. | 14 Countries & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) | - |

Newspaper/Magazine cover/bag | 3 Countries | - |

Plastic bags | 94 Countries & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) | 44 Countries & 2 Regions (EEA – 30 member states, & Barcelona Convention – 21 contracting parties + the EU The European Economic Area and the Barcelona Convention overlap by 8 countries, therefore the total number of countries counted here is 43 (30 from the EEA and the 13 countries from the Barcelona Convention that are not members of the EEA). |

Plastic confetti | 1 Country | - |

Plastic laundry covers | 2 Countries | - |

Plastic packaging (general) | 7 Countries | 21 Countries & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) |

Plastic flags | 1 Country | - |

Plastic produce labels | 2 Countries | - |

Plastic trays/platters | 5 Countries | 2 Countries |

Plates and bowls | 23 Countries & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) | 8 Countries |

Ring carriers Ring carriers are flexible and designed to surround beverage containers in order to carry them together. | 2 Countries | - |

Sanitary towels | - | 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) |

Sticks to support balloons | 6 Countries & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) | - |

Straws | 18 Countries & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) | 1 Country |

Tobacco products (incl. cigarette filters and packets) | 1 Country | 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) |

Wet wipes | - | 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) |

Table 2 lists examples of plastic-related polymers and monomers that have been banned or restricted, noting that some are for specific applications only. For example, the use of expanded polystyrene (EPS) in food and beverage packaging is limited in multiple countries and across the EEA. See Appendix 1 for further details of these regulations at the national and regional level, and Appendix 2 for the full set of references.

Table 2. Plastic monomers and polymers banned or restricted at the national or regional level.

See Appendix 2 for research reviewed to compile this table and related maps.

Plastic monomer or polymer | Banned | Restricted |

Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene | 1 Country | - |

Ethene | 1 Country | - |

Ethylene | 1 Country | 1 Country |

Polybutylene terephthalate | 1 Country | - |

Polycarbonate | 1 Country | - |

Polyethylene | 5 Countries | 1 Country |

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) | 4 Countries | 3 Countries & 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states) |

Polyphenylene oxide | 1 Country | - |

Polypropylene | 3 Countries | - |

Polystyrene | 18 Countries | 1 Region (EEA – 30 member states)- |

Styrene | 1 Country | 1 Country |

Polythene | 3 Countries | 1 Region (EAC – 8 partner states) |

Vinyl | 1 Country | - |

Polyvinyl | 1 Country | - |

Vinyl chloride | 1 Country | 1 Country |

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) | 3 Countries | 1 Country |

Although the examples of current regulations highlighted above represent a small component of the full range of polymers and products that may be identified as PUA, the overview provides a strong basis for broadening the scope of action through a globally harmonised approach.