6. Analysis

In this section, the implementation of EPR is analyzed. In section 6.1 different kind of responsibility are discussed and in section 6.2 fee structures and take back policies is analyzed. In section 6.3 a comparative analysis between the observations from the Nordics is presented, focusing on producer definitions, how EPR is carried out. Barriers, success factors, and lessons learned from the implementation of EPR are also compared and considered.

6.1 EPR – Different kinds of responsibilities

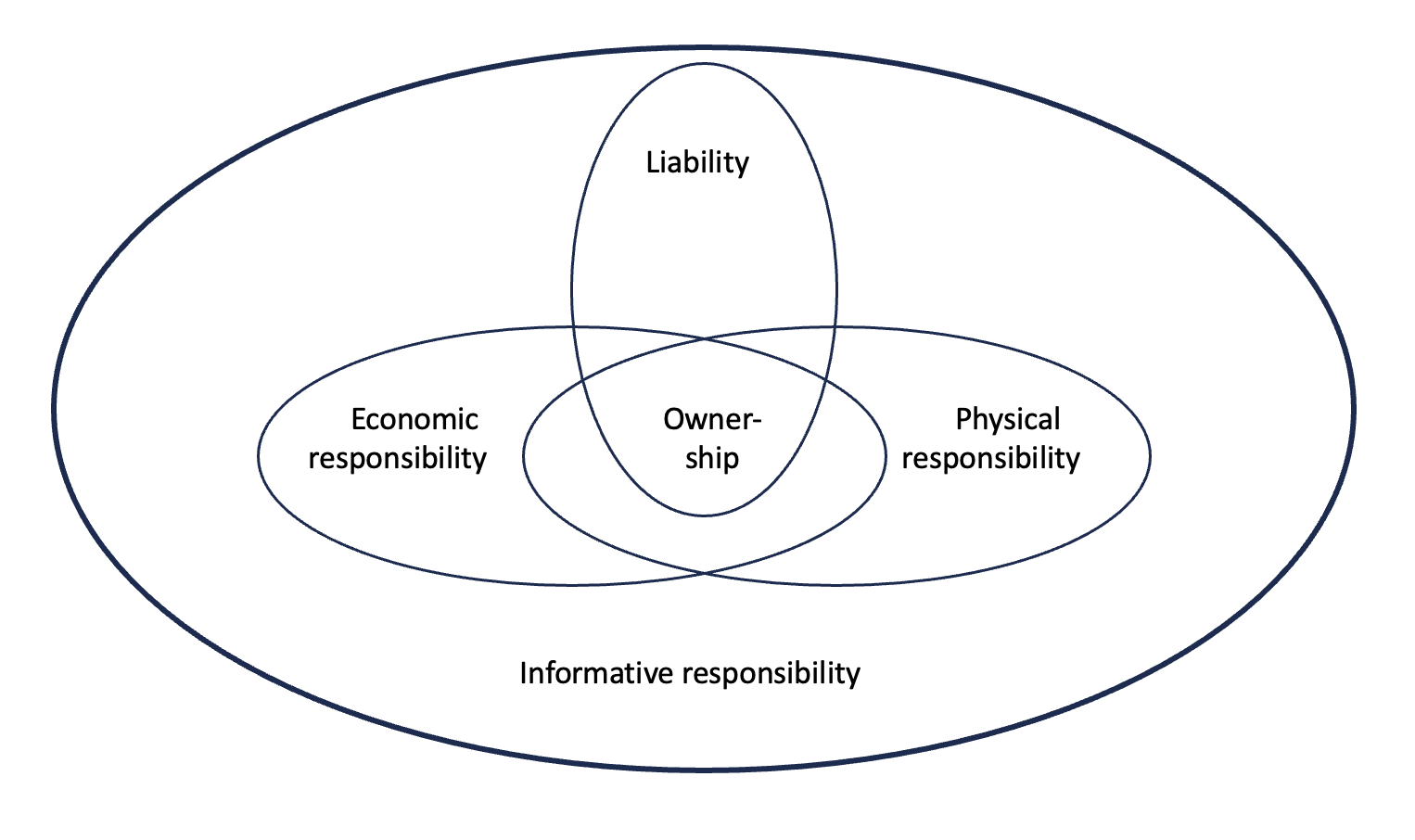

Lindhqvist (2000) presents four categories of producer responsibility: liability, physical, financial, as well as informational responsibility. Liability refers to the accountability that producers could be held to for any environmental harm derived from their products. Physical responsibility manifests in the obligation of actively participating in the management of waste products, i.e., in the collection, sorting or disposal of waste products. Economic responsibility, on the other hand, is the financial obligation of handling costs related to this waste management. Lastly, the informative responsibility refers to producers informing and spreading awareness to consumers about proper recycling practices. (Maitre-Ekern, 2021)

Figure 2. Models for Extended Producer Responsibility. Source: (Lindhqvist, 2000)

Based on Lindhqvist, others have made distinctions between the different approaches to EPR or, as some call it, different levels of responsibility that producers typically take on. Generally, there’s a distinction between a financial model, a hybrid model (with partial operational responsibility), and a full operational model. The financial model is where producers assume financial responsibility, while municipalities bear the operational burden of waste management. In contrast, the operational model is where producers assume both operational and financial responsibility for waste management, including collection and sorting. However, these tasks can be outsourced to professional collection and treatment services. The hybrid model entails shared operational responsibility between municipalities and producers. In this model, the responsibilities can shift between tasks and stages of sorting the waste. (Deloitte, 2020) (Pouikli, 2020)

Moreover, there is a wide range of organizational models for EPR schemes. Firstly, many schemes offer the flexibility to impose responsibilities on producers either individually or collectively, through Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs). The latter is more common, and producers can then organize themselves and share responsibility within the same product category, sector, or the same waste streams, and finance the collection and/or recycling of producers through the PRO. Notably, a collective scheme entails equal contributions from all members, regardless of the specific recycling capabilities of each product. This approach offers limited incentives for improving product design. On the other hand, individual responsibility proves more effective in promoting better design because producers face the actual costs of managing their products at the end of their life cycle, though it presents practical challenges. (Deloitte, 2020)

EPR schemes can also be either mandatory, making it compulsory for producers to take part, or voluntary, i.e., producers have the option to participate. (WWF & Institute for European Environmental Policy, 2020)

6.2 Implementation of fee models and take back policies

In the implementation of EPR, there seems to be two types of problems in the design of EPR instruments. The first type of problem is that EPR is considered to have the ability to reach different objectives at the same time. Oftentimes, these objectives are general and vague. For example, Walls (2006) observes that there are many different environmental objectives associated with EPR. Some objectives that EPR systems are supposed to reach include reduced generated waste, waste disposal as well as littering and hazardous waste. EPRs are also often expected to decrease material use while simultaneously increasing recycling rates. Moreover, EPR is described in reports from the Nordic Co-operation as an instrument to mobilize private resources for waste management and to promote circularity. Circularity is a general goal that can be reach in many ways, and the design of an effective policy for circularity is not necessary the same as one that mobilize private resources. If environmental objectives for policy instruments are not clearly defined, it will inevitably lead to design difficulties that jeopardizes possibilities to reach desired environmental improvements.

The second type of problem in the implementation of EPR is that policy instruments often fail to distinguish between behavioral objectives and environmental outcomes of the instrument. In terms of objectives from a behavioral perspective, it is important to distinguish between objectives and outcomes. Policy instruments, if well designed, strives to make polluters pay for the damages they cause in the economy. Even if the policy instrument is not well designed, its objective is to change behaviors. This will lead to several incentives throughout the economy that lead to seemingly different effects. An environmental tax or a fee has the objective to change behaviors, i.e., introduce incentives in the economy, with the aim to reach desired outcome such reduce generated waste, reduce waste disposal, reduce hazardous waste, and decrease material use. Not distinguishing between the behavioral objective and the environmental outcome can lead to wrong or unnecessary policy adjustments, which may increase policy costs and in the long run may question the environmental policy instruments legitimacy. One common misconception is for instance that specific policy instruments are necessary to increase circularity and to reduce material intensity in the economy. In many cases, it may be enough to design stringency of environmental regulation in proportion to the waste generated by each product.

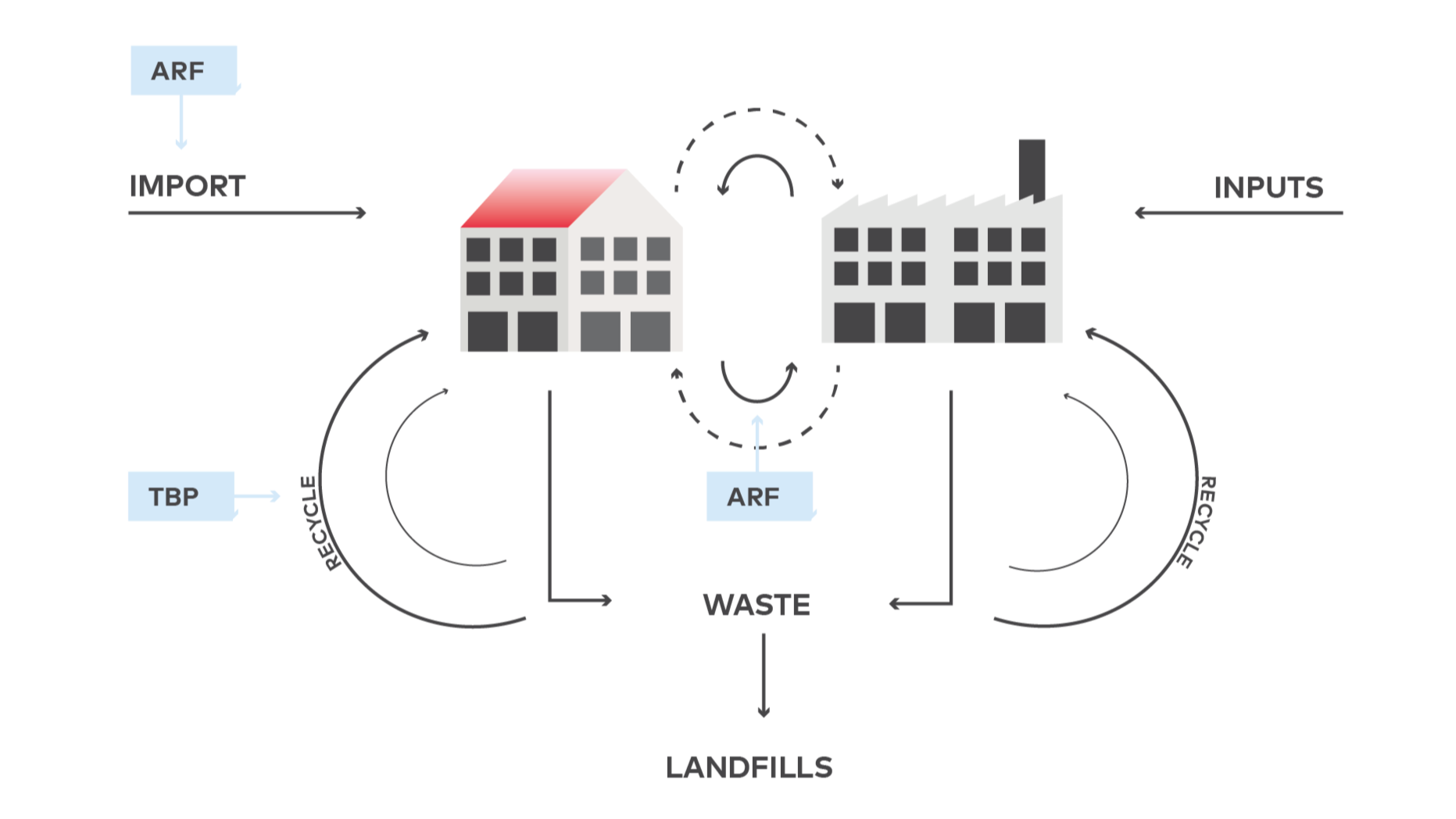

Figure 3. The implementation of EPR instruments Advanced Recycling Fees (ARF) and Take Back Policies (TBP) in Nordic countries.

Figure 3 shows where in the economy Advanced Recycling Fees (ARF) and Take Back Policies (TBP) are implemented. ARF, or differentiated producer fees, are fees paid by producers, i.e., those introducing products in the market (which may be manufacturers, importers, or resellers) in relation the amount of material they put on the market and how easy it is to recycle. For plastics in packaging, ARFs target import of packaging or packaged products and production of packaging. TBPs on the other hand target how much of the waste is collected and recycled back to the economy. Mandatory collection systems combined with recycling targets is a good example of TBPs.

In Figure 3, it is obvious that these EPR instruments do not directly target the amount of waste generated from households or industries. In a well-functioning economy, policies set upstream at producers or downstream at consumers will have full effect in the economy, and ARF and TBP can be enough to obtain efficient solutions. Calcott and Walls (2000) and Fullerton and Wu (1998) have shown that when recyclability is perfectly observed in the economy and market failures due to undefined property rights do not exist, well designed ARF and TBP are enough to reach efficient policy outcomes. In a more realistic model, for instance when recyclability is difficult to observe, Calcott and Walls (2005) show that an optimal combination of policy instruments, need to include disposal fees in addition to ARF and TBP. The literature emphasizes that EPR may contribute to improvement, but that it is not enough for achieving effective management of waste in the transition toward a circular economy. All streams of material in Figure 3 are potential means to affect waste, and an efficient policy package is one that exploits all these means such that their cost on the margin is equal. That is, the marginal cost of reducing waste or increasing circularity by design, recycling and depositing waste should be equal. A policy package that is directed to exploit only some of these means can evidently not reach this efficient outcome. In other words, EPR policies need to be coordinated with other policy instruments for waste management. If waste is not reduced or circularity increased, EPR policies will only shift material flow to other unregulated or less regulated streams in Figure 3 and the overall waste policy will not improve and maybe even become less cost-efficient. For instance, if landfilling is under- or unregulated and relatively cheap, more material will be landfilled.

As already noted from Figure 3, it can be observed that ARF does not directly affect waste. This results in some regulation difficulties as it is challenging to observe how much waste can be prevented by design. Even if material-intensity may give some indication of how to regulate, the final impact of waste in the economy is related to other factors such as recyclability, durability, and toxicity, that are difficult to observe upstream in a product’s lifecycle. If the ARF can be adapted and differentiated to reflect the degree of recyclability, durability, and toxicity, then it would create strong incentives for good design that could prevent waste and increase circularity. However, in most cases, these factors are difficult to observe, and ARF has limited capacity to create these incentives.

Take-back-policies (TBP) often consists of targets for recyclability. That is, reuse of goods, material and energy, and different measures to reach these targets. To reach these targets it is often necessary to invest in an infrastructure for sorting and collection of materials, which raises the need for policies to pay for these investments. Calcott and Walls (2000) and Fullerton and Wu (1998) discuss that subsidies for recyclability are instruments to reach effective TBP. In Figure 3 it can be observed that take-back-policies (TBP) are close to the stage when waste is generated. Since one criterion for efficient policy instruments is that policy instrument is set close to the source of the problem, TBP have the potential to reduce the amount of waste that goes to incineration or landfill by increasing recycling. The incentives created in the economy depend however on how TBP are financed. In EPR schemes the idea is that producers pay for recycling, thus there are great opportunities to design effective TBP policies within EPR.

When TBP are implemented in EPR schemes in many countries, including the Nordic countries, they are often financed by different kinds of ARF. Actors responsible for EPR in the Nordic countries in the interviews reveal that produces take the economic responsibility by the fees they pay to PRO, which based on costs of their activity for recycling have fees are used to activities to increase recycling. The basic principle for determining the level of these fees is to cover costs for recycling or other waste management. The incentives introduced by such financing systems are however odd in relation to the recycling targets. First, it can be noted that costs for recycling are not necessary cost to reach the targets. Often cost to reach targets may include investments in new technologies, infrastructure or ideas that are not related to the actual costs of recycling. Second, since the level of ARF is determined by PROs or government agencies that use historical data (data from the previous year), the incentives are created by historical costs, which do not mirror costs for reaching recycling targets. Third, the cost covering principle may introduce contra productive incentives. This is because the producer’s costs for recycling depend on the volume of material recycled, and accordingly, the economic incentive in the market is to keep the recycling volume as low as possible. To introduce incentives in line with the intention of increasing recycling and reducing generation of waste the level of ARF should be more related to the costs of reaching targets. Such as that ARF instead of compensating costs for recycling rewards efforts to increase recycling. Note that differentiating fees with the degree of recyclability do increase recyclability but do not necessary reach a specific target for recycling. One such case is when recycling capacity is exhausted and investment in recyclability capacity is necessary.

One of the major challenges with regulating waste generally and implementing EPR specifically is that waste is generated in a complex economy. Waste is a residual of many streams of materials and as such, the actors that are involved are many and difficult to observe. A well-designed policy instruments should assign responsibility in proportion to the waste each producers generate. However, in a complex economy and when EPR by design attempts to assign responsibility to producers upstream in the market in order to regulate household waste downstream it is extremely difficult to assign responsibility to each producer in proportion to the waste they generate. Therefore, when EPR schemes are implemented, it is necessary to find pragmatic solutions. One such solution is collective take back responsibility, that is producers collectively are responsible for sorting, separation, and recycling of waste. This is often designed such TBP are financed by ARF, which inevitably leads us to conclude that the financial responsibility producers take is not related to the amount of waste they generate. This means that EPR have difficulties introducing incentives that follow polluter pay principle and therefore alone struggle in achieving efficient policy outcomes.

To conclude, EPR is best introduced in combination with other policies such as weight differentiated waste fees for households (common in many Swedish municipalities) and landfill bans, high landfill taxes or other restrictions. It is also important to keep track of statistics of volumes put on the market versus what is collected and recycled, to ensure that producers take the responsibility all the way to recycling of their products.

6.3 Barriers, success factors and lessons learned

Financial and operational models

Producers in all countries have financial responsibility in some way, except for in Denmark where this is about to be implemented. For instance, in Sweden, this entails responsibility over waste management, ensuring collection systems exist, and the design and development of recyclable products. On top of this, Swedish producers must take informative responsibility concerning making the public aware of how waste should be sorted and how it is collected.

Sweden and Denmark also exhibit different strategies regarding responsibilities. Sweden is shifting the operational responsibility for plastic packaging waste to municipalities in an effort to simplify the sorting process for households and increase collection rates. It has been observed that municipalities with curbside collection (collection in or close to consumers’ homes) have higher collection rates. The municipalities are then paid by the producers for their efforts, following a reimbursement model overseen by the competent authority (SEPA). Denmark, on the other hand, is introducing producer responsibility for packaging through new regulations, and in doing so, shifting the responsibility from municipalities to producers.

Overall, collaboration between producers, municipalities, and PROs, coupled with transparent systems, seems to contribute to effective implementation of EPR schemes, as long as the responsibilities are clarified, and economic models are negotiated and accepted by all parties.

Different design requirements, reporting standards and fee levels in all member states make EPR compliance a resource-intensive task for producers, who often call for more harmonized legislation. However, achieving a common EU-level regulation could also be challenging due to variations in how different countries implement it. Another commonly discussed issue is the problem of direct import by consumers which is hard to control and regulate and that not all products are manufactured within the EU.

Vague definitions

The significance of clear and well-defined legislative frameworks cannot be overstated in the context of EPR success. The Nordics generally define producers as companies that “put plastic packaging or packaged plastic goods on the market for the first time”, targeting manufacturers and importers. However, these definitions are fairly broad with some nuances among the countries. For instance, Sweden and Finland include "distance sellers” or foreign enterprises that offer packaged items to end-users in their respective nations. Norway, in contrast, has a more defined concept, requiring a minimum quantity (1000 kg) of a particular package type for producer classification. However, there is a proposal to revise Norway's definition, possibly lowering the threshold for who is classified as a producer by removing or changing the quantity limit, potentially affecting recycling targets.

Simultaneously, Finland is taking a different approach requiring producers with a yearly revenue of more than 1 million EUR to bear responsibility. However, starting 2024, all producers irrespective of revenue will be included. In this case, there are concerns regarding increased administrative costs that will lead to more difficulties with compliance and ultimately more free riders in the system as producers avoid joining PROs. Again, it could lead to unfulfilled recycling targets.

Free riders

The extent of free-rider issues also varies among countries, and apart from the unclear definitions and legislations, this could be derived from the lack of supervision and sanctions toward those producers that do not take responsibility or simply fall outside the producer definitions. While Sweden faces significant challenges with this within its system, Iceland’s EPR system stands out as the only country without significant issue of free-riding producers, possibly because producers in Iceland are obligated to pay fees, leaving them with limited options for avoidance. Such a system could be facilitated by Iceland's relatively small size, which may make it more manageable.

Fees and reporting of data

The Nordic producers all have to report data and pay fees associated with their packaging, to cover operational recycling costs. However, these fees are structured in different ways and the reporting standards and design requirements vary.

For example, Sweden has voluntary implemented ARF in the shape of two differentiated fee systems based on recyclability, which has had a positive impact on recycling targets but is still not fully effective. This can be compared to Finland where material composition and packaging type is considered in the fee level set by a single PRO, that is also based on data from the previous year. The fees also differ between consumers and producers. Iceland also stands out in this context because they have an ARF in the shape of a tax applied to all producers of plastic without them having to join a PRO. This is closely tied to and dependent on the actual costs of waste management, the amount of waste collected, and the recycling targets. However, Iceland currently lacks differentiated fee structures but are about to introduce it.

Another important lesson from all countries is the importance of a correct calculation method to determine recycling rate. The previous method where packaging going into sorting was considered as recycled has been proven to result in false, inflated recycling rates. The correction of this flaw has a risk of undermining the public trust in the recycling industry, and in the collection system, making people less inspired to sort their waste correctly.

Flexibility in adjusting fees to align with changing targets can help promote recycling targets and incentivize producers to design recyclable or reusable products. The introduction of minimum requirements for differentiated fees is expected to yield economic incentives for the design of recyclable products.

Deposit systems could lead the way

One type of system that is considered effective is the deposit-refund system, due to their high collection rates. This is driven by financial incentives and increased recycling rates resulting from standardized material quality of recycled PET (rPET). For example, the systems cover a limited range of products and have strict product design guidelines, while also providing clear instructions for recycling and returns. In contrast to other systems, deposit-refund systems offer a financial incentive for consumers to return containers for recycling. The Swedish voluntary producer responsibility system for silage plastic (SvepRetur) is also deemed successful, for similar reasons, such as focusing on a single product and maintaining a clear and clean material flow. Notably, this system functions effectively even though it operates voluntarily.

Thus, for the deposit systems, there is incentive to design according to strict guidelines, which is seemingly absent in the context of EPR for other types of packaging. The current design requirements for packaging lack specificity, making them challenging to control and monitor. In the upcoming EU-level proposal currently under negotiation, there is a clear emphasis on incorporating more stringent design criteria for packaging, with a focus on ensuring that the product materials are recyclable. These upcoming requirements are expected to provide more specific guidelines, particularly regarding the segregation of different plastic types. It is anticipated that the upcoming requirements will incentivize product design, similar to deposit-refund systems, thereby contributing to enhanced recycling outcomes as waste streams become more refined. In parallel, ongoing EU level work to develop more material quality standards for recycled plastic fractions will be helpful to drive markets for recycled plastics.