3. Extended Producer Responsibility

The concept of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) was introduced in a seminal work by Lindhqvist in the 1990s. The Nordic countries are often recognized for best practices of implanting EPR (see for instance Roman (2012). Lindhqvist’s work also provided the following definition of EPR:

"Extended Producer Responsibility is an environmental protection strategy to reach an environmental objective of a decreased total environmental impact from a product, by making the manufacturer of the product responsible for the entire life cycle of the product and especially for the take-back, recycling and final disposal of the product. Extended Producer Responsibility is implemented through administrative, economic, and informative instruments. The composition of these instruments determines the precise form of the Extended Producer Responsibility." This definition brings up some interesting aspects worth noting:

- Producers

- The responsibility of producers in EPR can be of different kinds.

- Which kind of responsibility producers should have in EPR depends on product-specific characteristics and the objectives of the specific EPR legislation.

EPR has become popular and today there is extensive literature, especially among policymakers and authorities involved in implementing producer responsibility in environmental policies around the world, nonetheless in the Nordic countries.

Some useful insights for policy can be found in some studies conducted by the OECD. The OECD has elaborated the definition of EPR and emphasizes that the focus of producer responsibility lies on the final stage of a product’s life cycle. The OECD defines EPR as “an environmental policy approach in which a producer’s responsibility for a product is extended to the post-consumer stage of a product’s life cycle” (OECD, 2016). The post-consumer stage means that the product in question has already been used and disposed of by a consumer. EPR is further described as a way to shift responsibility (physically and/or economically) upstream toward the producer and away from municipalities, so that producers have incentives to take environmental considerations into account even when designing their products. The design aspects considered in relation to EPR are often related to recyclability, such as choosing materials and material combinations that do not interfere with current recycling processes, or designing products that can be easily dismantled and repaired or separated for sorting and recycling.

OECD’s position is interesting and has implications for the incentives that are created in an economy. In general, markets function well when property rights (defined in more detail in the next section) are well defined. However, when there are problems in asserting property rights, market mechanisms are not enough to deliver the amount of goods desired or damage to commonly owned goods and services (such spread of harmful substances in rivers, lakes, and seas). Overproduction of waste in the economy is one such case. The OECD definition is more precise, and it is an attempt to correct this deficiency in the market, that is, assign responsibility when property rights are difficult to determine in their final stage of life cycle and turn to waste.

3.1 EPR – Towards more efficient environmental policy

EPR and the problem with property rights for waste

Property rights and ownership are fundamental concepts in economics, law, and society that define an individual or entity's legal claim to control, use, and benefit from a particular asset or resource. These concepts play a crucial role in shaping the way societies allocate and manage resources, create wealth, and maintain order.

In most cases, property rights are based on the principle that ownership of a product renders rights as well as liabilities to the owners. However, there are cases when determining ownership of goods can be complicated. One such case is waste. This is the basic problem that needs to be regulated.

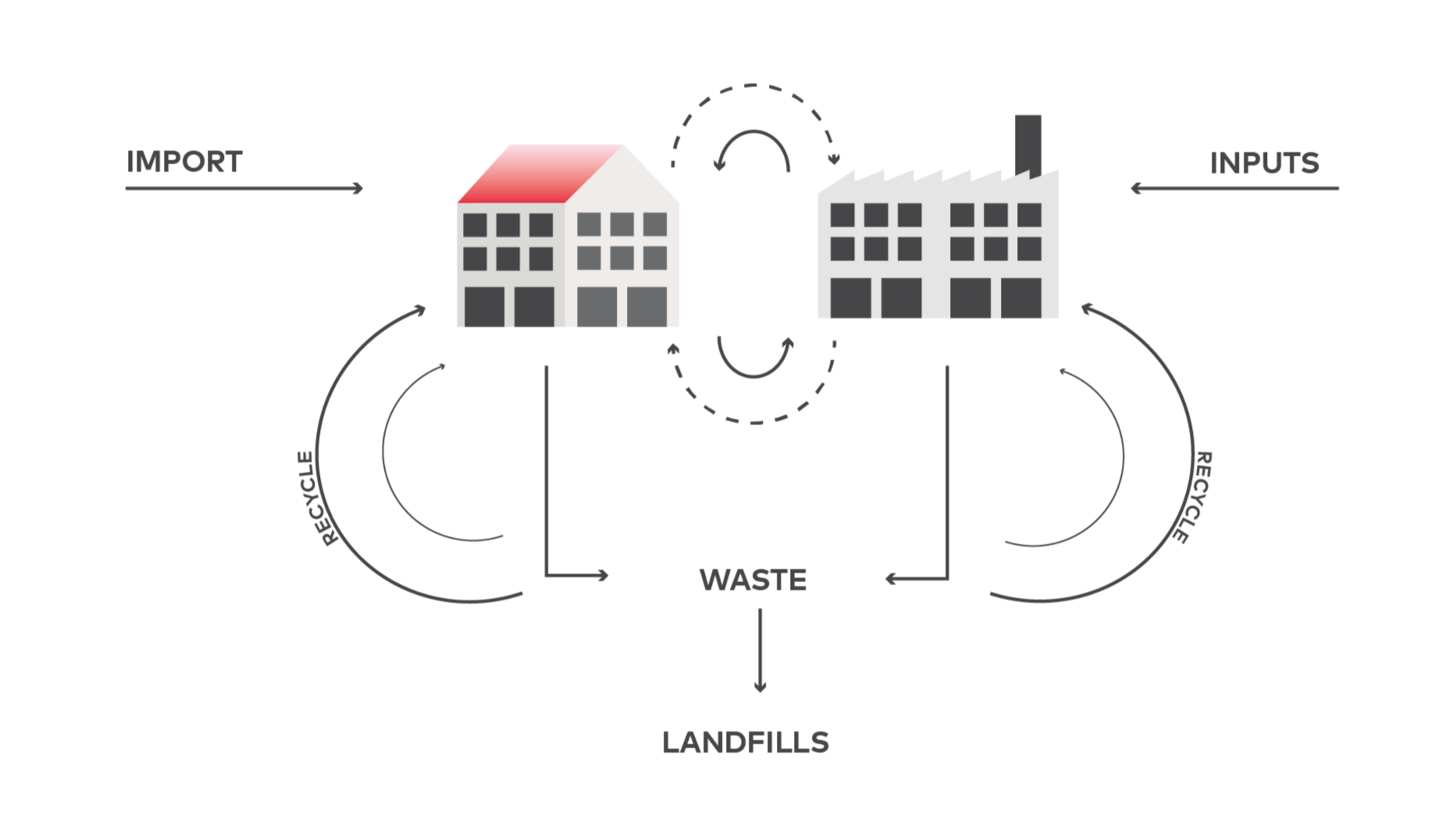

The basic problem can be illustrated as in Figure 1. Resources needed to produce and consume goods are continuedly brought from nature and generate a constant rate of waste. If nature’s assimilative capacity can take care of the generated waste, there is no problem. However, in modern economies the amount and the environmental effects of waste are large and over time accumulate and lead to high economic damages.

Figure 1. Different streams of material that affect the volume of waste are described.

Extending responsibility is one possible solution to the problem. The main idea from Lindhqvist is that producers are responsible for environmental impacts of goods and products. In the case of waste from household, it is generated from goods that producers no longer own, which is a step away from the basic principle that responsibility is closely related to actors’ ownership of goods and products. OECD is more specific in its definition of EPR and makes an important contribution by clearly pointing out that producer responsibility should be extended beyond the consumption stage. As such, OECD emphasizes the gap in environmental regulation that EPR can close. In this sense, EPR has a specific and unique role in regulating environmental impact beyond the consumption stage when it comes to waste from consumers or households.

Determining ownership of waste, when products no longer have a commercial value, in a complex economy with many streams of products, is difficult. Consequently, demanding responsibility for products environmental impact when they are discarded is difficult, which is discussed in the next section.

EPR as a complementary policy

The EU defines waste as a substance or object that its holder discards, intends to discard or is required to discard (European Commission, 2023a). In a complex modern economy, owners can discard or leave goods when they are no longer of use. This can cause different kinds of problems and damages to society, such as littering. As discussed in the previous section, this is related to difficulties in establishing property rights and connected responsibilities.

Traditionally, responsibility and costs for waste management have been taken over by society. In Sweden and many other countries, collection of municipal waste from households is the responsibility of the municipalities under a strict monopoly. Although taking over such responsibility often leads to well-functioning waste management, it also comes with high management costs. This is because, in principle, generating waste is costless to households in the economy. Consequently, there is a lack of incentive to reduce waste, as the costs for waste management are passed on to society.

As already noted, EPR assigns responsibility to producers. This way, some problems related to the lack of incentive to reduce waste management are addressed. Because the amount or volume of produced and introduced materials on the market is related to the amount of waste generated, the latter can be used as a “good enough”-indicator of relevant policy instruments. If implementing EPR can make producers reduce the amount of material introduced to the market by presenting higher waste management costs for producers, then it is also a useful tool within environmental policy.

An obvious challenge is that producers are made responsible for environmental problems in the consumption stage. In a well-functioning economy, policy instruments to lower waste will create incentives upstream or downstream the different stages of the economy. However, because determining property rights of waste is difficult, these policy instruments are challenging to design effectively. Complementary policy instruments that can reduce environmental damage related to waste are therefore needed. Assigning responsibility to producers, i.e., implementing EPR systems, is potentially one of these complementary instruments.

It is still worth reflecting on whether EPR meets the criteria for an effective policy instrument when the responsibility of producers is limited to the post-consumer stage. In theory, the two most common criteria for effective design of environmental policies are the polluter pay principle (PPP), and to put regulation as close as possible to the source of the environmental problem. The polluter pays principle ensures that the costs of pollution and environmental degradation are paid by those responsible for causing them. When polluters are required to bear the costs of their actions, they have a financial incentive to reduce pollution which leads to more efficient resource allocation. The second criterion for an effective policy instrument is to place regulations close to the source of environmental issues, which leads to precise and tailored signals in the market to reduce environmental damage. When regulations are further away from the source, the signals are less clear, and actors may adjust to the regulations without even reducing environmental impact.

EPR, even as defined by the OECD, has problems with both these two criteria. A lot of waste is generated by consumers and although the amount of waste is related to the amount of material introduced by producers, a large part is closer related to consumer behavior rather than that of producers. If there is an overconsumption of households that generates waste, for instance, the overconsumption itself or the consecutive waste generation can hardly be reduced by putting responsibility on producers, even if the producers may increase the recycling of what is consumed. The reason is that the waste-generating behaviors, i.e., the source of the problem, are not targeted through EPR. When the responsibility lies with the producers, which is far away from consumer behaviors it may lead to adjustments by producers that have little to no effect on consumers behavior and in turn, on the amount of waste generated at the consumption stage.

As long as consumers behavior is not targeted, any responsibilities taken on by producers will at best shift the waste generating behaviors from one product to another or create a recycling market, without affecting the market of new goods with virgin inputs. Ultimately, EPR needs to be combined with other policies that target consumer behavior to achieve efficiency as an environmental policy instrument.