3. Perceived quality and benefits of language training services

The purpose of this chapter is to present an analysis of our empirical findings concerning how three groups of stakeholders – participants in language training, providers of language training, and employers – perceive the quality and benefits of the language training services available in the Nordics. The chapter considers the differences and complementary nature between formal and non-formal services. It also compares perceptions between countries and, where applicable, sub-groups of immigrants. The empirical findings presented in this chapter are based on the results from the surveys conducted with participants and providers, desk research, interviews with providers and employer and employee representatives, as well as findings from the case studies.

Please see section 1.3 for a discussion of how bias affects the results of the survey.

3.1 Summary of findings

Overall, we have found few differences in how different sub-groups of immigrants and providers across the Nordic countries perceive quality and benefits of training. While conditions, as previously described, vary between sub-groups in terms of eligibility for formal language training, their perceived goals, obstacles, and quality factors are largely similar. The main differences are instead related to the extent to which a certain goal or obstacle is particularly important. For example, labour migrants find lack of time a larger obstacle than other sub-groups. Otherwise, individual circumstances and backgrounds seem to be more important. There are also surprisingly few differences between the Nordic countries in terms of motivations, obstacles, and quality factors. The main identified difference is the extent to which formal language training is considered high-quality, where stakeholders from Sweden ascertain that the Swedish system has a lower quality than the systems in Denmark, Finland, and Norway.

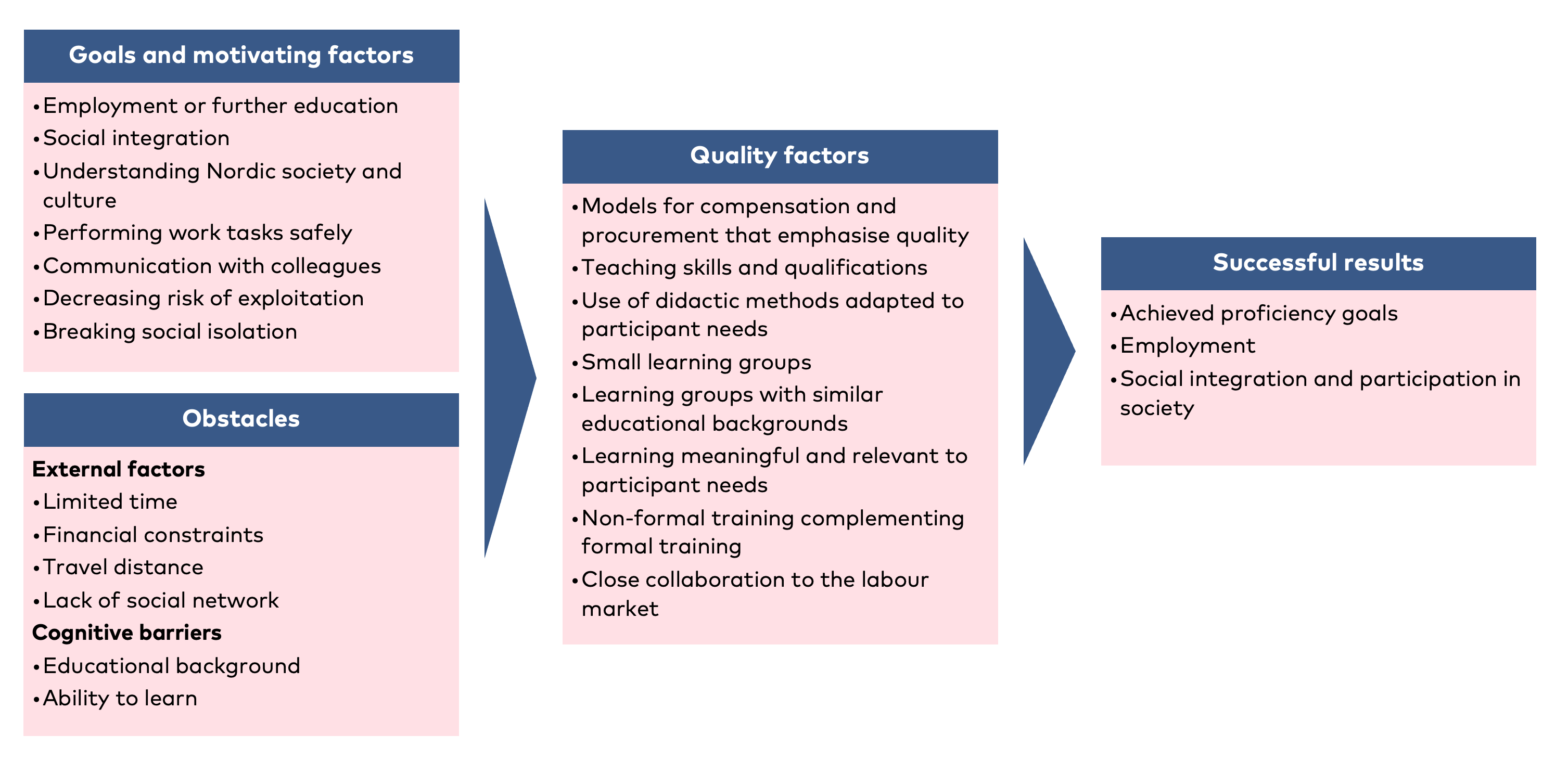

Perceived quality in language training is a complex issue, that can be understood in many ways. For the purpose of this study, we find it useful to understand quality as the way in which an initiative or service must be delivered in order to achieve success. As such, we consider quality to be when a language training service is delivered in a way that enables participants to be successful in achieving both their own and society’s goals for language training by increasing their motivation and helping them to overcome barriers. As illustrated in Figure 2, this means that the service must be organised in a way that enhances learning and motivation by being meaningful as well as making it possible to overcome barriers related to both external conditions (e.g. lack of time, travel distance, financial constraints, trauma or a lack of social network) and cognitive barriers (e.g. educational background, ability to learn). But also contributes to participants achieving their ultimate goals.

Perceived quality in language training is a complex issue, that can be understood in many ways. For the purpose of this study, we find it useful to understand quality as the way in which an initiative or service must be delivered in order to achieve success. As such, we consider quality to be when a language training service is delivered in a way that enables participants to be successful in achieving both their own and society’s goals for language training by increasing their motivation and helping them to overcome barriers. As illustrated in Figure 2, this means that the service must be organised in a way that enhances learning and motivation by being meaningful as well as making it possible to overcome barriers related to both external conditions (e.g. lack of time, travel distance, financial constraints, trauma or a lack of social network) and cognitive barriers (e.g. educational background, ability to learn). But also contributes to participants achieving their ultimate goals.

Figure 2. Illustration of factors that affect the benefits and successful results of language training

3.2 Why do immigrants participate in language training?

There are many reasons why immigrants participate in language training. The obvious ones are related to regulations; for unemployed immigrants in all countries, participation in language training is often a requirement to receive financial support. But this is far from the whole picture. Motivations to participate in language training are related to both personal circumstances and ambitions, as well as a wish to participate in Nordic society. While social integration as well as understanding the new society and culture are important results of language training, the primary reason for participation in language training identified in this study is labour market integration, both in terms of gaining employment and functioning in the workplace. This is in line with political priorities in all the Nordic countries, where integration policies highlight language training as a key to integration, with policies and integration programmes being designed accordingly.

The motivations to participate in language training are remarkably similar across immigrant sub-groups. The main difference lies in the differences between labour migrants who are already employed, and immigrants who are unemployed, regardless of their background. Where employers, providers, and participants across all countries agree that gaining employment or achieving the proficiency required for further education is the primary aim of language training among unemployed immigrants, for labour migrants or other immigrants who have gained employment, the reasons are more complex. Here, the primary reasons are being able to perform the tasks of a job in a safe manner, mitigating the risk of exploitation, and improving social integration.

Participating in language training solely for the goal of social integration is unusual

Please note that this could be due to selection bias among survey respondents and interviewees.

Language skills are key to gaining employment

Overall, there is widespread agreement among stakeholders that the aim of language training should be to facilitate labour market integration among unemployed immigrants. As well as being the explicit aim of formal language training services for adult immigrants in all the Nordic countries, the goal is echoed both among the participants themselves, as well as employer representatives in all countries. The latter consider language training a crucial element in being able to meet their demands for labour. Among surveyed participants, entering the labour market is considered the most important reason to learn a Nordic language among immigrants to all countries

Annex B: Figure B 1

On the other hand, the focus on labour market participation as the goal of language training also means that employment may be prioritised over language learning. While employment can be highly beneficial to the development of language skills, providers and employee representatives in Denmark and Sweden also point out that it is not uncommon for immigrants to stop participating in formal language training services once they gain employment, regardless of their proficiency (or lack thereof). The interviewees consider this to be detrimental to the immigrants’ continued language development, particularly if the job does not give opportunities to practice their language skills. This was the experience of an interviewed immigrant to Norway who explained how leaving language training to work and care for his family meant that he failed to develop written Norwegian skills, despite having lived in Norway for over a decade.

Language skills are necessary for workplace integration and safety among employed immigrants

Finding a job is, however, only one part of how language training is important to labour market integration. Both participants and employer representatives highlight social integration as an important aspect of employee retention, particularly among labour migrants. An interviewed high-skilled labour migrant in Norway whose working language is English explains how learning Norwegian is a way for them to improve their social integration, as they plan to remain in Norway long-term. This point is reinforced by survey results, which show that understanding Nordic culture and society is another key reason that immigrants participate in language training.

Annex B: Figure B 2

For most immigrants, sufficient language skills are also necessary to be able to function in a workplace, performing tasks with necessary safety precautions and communicating with colleagues. As highlighted by an interviewed Swedish employee representative, employees who do not have sufficient language skills can pose a risk to the organisation. For example, within the healthcare sector, there are substantial risks to patients if communication is not clear. Employees must be able to understand and adhere to safety regulations, communicate any issues at hand, and avoid misunderstandings insofar as possible. While this applies to all sectors, the interviewee maintains that it is particularly important in sectors that employ many immigrants, such as healthcare, industry, and construction among others. In addition, according to an interviewed representative from an employee organisation in Finland, the ability to speak and understand the national language is an important aspect of employee rights. Without this ability, immigrants have an increased risk of exploitation.

While language training enhances the social integration of labour migrants, there is little data available concerning the extent to which employers actually provide language training to employees who are not eligible to participate in formal language training services. There does, however, seem to be a difference between countries in terms of the extent to which employers take on these responsibilities, with Norway standing out as having a heavier focus on employer responsibilities. Nevertheless, as per an employee organisation in Finland, employers do provide language training for labour migrants to a certain extent. This is, however, not a widespread practice and particularly unusual for labour migrants in low-skilled occupations. In Norway, on the other hand, employers seem to take a larger role in providing training to labour migrants. According to interviewed employer representatives and providers, this language training typically takes the form of short, targeted courses offered by non-formal commercial providers in a traditional learning setting. While employers are often happy to offer short courses that are quick and efficient and provide basic skills, employees find that language learning requires both effort and time to process and practice what they learn. Data from Denmark and Sweden on this subject is limited. Given that all immigrants have access to formal training, the need is for such services targeted at labour migrants and immigrant employees is less substantial.

Language skills contribute to social integration

While employment may be the ultimate goal and purpose of language training services, social integration is another important aspect. Labour market integration and social integration go hand-in-hand, but for immigrants who have limited possibilities of joining the labour market in the short term due to lack of skills or family commitments, social integration can be the most important goal. While individual circumstances affect this, these obstacles are particularly prevalent among refugees and their family members.

Nordiska Ministerrådet (2021)

3.3 What prevents immigrants from achieving their goals with language training?

The main obstacles that prevent immigrants from either participating in language training or achieving their goals that have been identified in this study, affect all immigrant sub-groups – if in different ways and to varying extents. Barriers related to eligibility are difficult to overcome without changes in regulations. However, even for sub-groups that are ineligible to participate in formal language training, there are non-formal language training services available. This section thus explores the obstacles and barriers to participation on a more general level.

Challenges such as limited time to participate, lack of social networks, financial constraints, and missing educational prerequisites are not limited to any specific immigrant sub-group. The main obstacles to language learning primarily seem to come down to individual circumstances, with factors such as previous educational levels and family commitments affecting participation and ability to learn. A lack of social network or environment to practice the Nordic language is also considered a challenge across sub-groups and countries but can play out in different ways. For example, high-skilled labour migrants often work in English and socialise in English-speaking, international communities. Whereas for low-skilled refugees, the lack of social networks could rather be due to factors such as housing segregation, providing limited opportunities to meet native speakers in their daily lives. Based on this study’s findings, Figure 3 presents the main identified barriers in relation to how likely we consider that they will constitute a significant barrier to participation and goal achievement for different sub-groups.

Regardless of immigrant background, obstacles clearly can and do prevent immigrants from achieving their goals with language training. Whether the obstacles are due to external factors in immigrants’ lives or their innate cognitive abilities, they still constitute barriers that must be overcome. While an obstacle such as an uneven quality in the services delivered does not necessarily present a barrier to participation, it can affect the participants’ chances of achieving results, and could also be linked to high dropout rates.

Skolinspektionen (2021).

Refugees and their reunited family members | Family members of Nordic citizens arriving through family reunification | Labour migrants from EU/EEA countries | Labour migrants from outside the EU/EEA | |

Limited time | Less likely | Less likely | More likely | More likely |

Financial constraints | Less likely | Less likely | More likely (FI & NO) | More likely (FI & NO) |

Lack of social network | More likely | More likely | More likely | More likely |

Cognitive barriers (low education, ability to learn) | More likely | Less likely | Less likely | Less likely |

Figure 3. Barriers to participation according to their severity for different immigrant sub-groups

Participants have other commitments, limiting time for language training

A key challenge for adult immigrants to participate in both formal and non-formal language training activities is finding the time to do so. Among survey respondents, lack of time is the most significant obstacle to participating in language training, particularly among labour migrants.

Annex B: Figure B 3

Financial constraints may affect participation, but to a limited extent

While studies and experts agree that financial constraints can be an obstacle to participating in formal language training, neither the participants nor the providers surveyed in this study consider this to be a substantial obstacle to participation.

Annex B: Figure B3; Annex B: Figure B7

Rambøll (2021)

Approximately 10 percent of participants in Norwegian training in 2021 were labour migrants from outside the EU/EEA, who are obliged to participate (Statistisk sentralbyrå, 2021).

Udlændinge- og integrationsministeriet (2021)

Findings from interviews also show that financial constraints can present an obstacle to immigrants who are eligible to participate in formal language training at no cost. For example, a Swedish provider mentions how participants are unable to purchase the required course literature, affecting both the delivery of the service and the participants’ possibility to absorb what is being taught.

Immigrants lack social networks and opportunities to practice the language

Another factor that affects immigrants in their goal of learning a Nordic language is their lack of social network and relations to native speakers. Both providers and participants point out how immigrants of all backgrounds often have little opportunity to practice speaking in their daily lives. For refugees and their family members, the lack of contact with native speakers is often due to segregation. An interviewed provider in Sweden explains how it is difficult for these immigrants to find an environment where they can use what they are learning. A Swedish teacher mentions how their students sometimes call customer service numbers just to practice the Swedish they have learnt through training.

Interviewed labour migrants from Norway, Denmark, and Finland who speak and work in English also point out that the high levels of English in the Nordic countries mean that the Nordic language is rarely needed to communicate at work or in social settings, which primarily take place in international communities. They find that this slows their progress and makes it difficult to achieve fluency, despite considering themselves to have the abilities to succeed.

Educational prerequisites affect participants’ ability to learn

As well as the previously discussed external factors, immigrants’ learning is also affected by their cognitive abilities. These include both innate abilities to learn a new language, but also factors such as how many other languages they speak and their educational backgrounds. Research shows that educational background affects the ability to learn a new language.

AlHammadi (2016)

A lack of education can also mean that immigrants have less access to non-formal services, particularly non-formal traditional courses at private language schools. For example, an interviewed commercial language provider in Denmark points out that they require participants to have completed at least 12 years of education to participate in their language courses, since the learning speed is fast. There are, however, also a wide variety of services targeted toward this group, particularly social language services.

Nordiska Ministerrådet (2021)

Unevenness in the quality of delivered services

The obstacles to achieving the goals of language learning can also be related to the quality of the services provided. While the surveyed participants generally consider the standard of language training in all Nordic countries to be high, there are some exceptions. Sweden particularly stands out as having a formal language training system which participants and employers describe as “uneven”. An interviewed employer organisation in Sweden ascertains that an employee having passed a course does not necessarily guarantee that they have the expected proficiency. According to the interviewee, the quality of the students’ Swedish levels can differ enormously between schools. They also see a pattern of students passing courses too easily. This means that Swedish employers are often obliged to test potential employees’ Swedish skills and offer complementary training. Both employer organisations and non-formal providers in Sweden put the uneven quality down to a lack of qualified teachers, combined with providers letting participants pass their courses too easily. While interviewed experts in Denmark have also pointed out that the quality among providers can be uneven, these concerns are less prevalent than among the Swedish stakeholders. We have not identified these issues in Finland or Norway. However, an interviewed employer organisation in Denmark does highlight that the contents of language training are often very general. For labour migrants or other immigrants who have found employment, the training can be too general and far removed from the more specific and industry-oriented training that could benefit them.

3.4 Which factors are important to ensuring high quality language training?

A wide range of factors are important to how stakeholders perceive the quality and benefits of language training. The key factors we have identified in this study are:

The organisation of compensation models and procurement systems

- Skilled or qualified teachers using didactic methods adapted to the needs of participants

- Group composition and learning environments

- Relevant and meaningful training

- Non-formal language training services that fill the gaps left by formal services

- Close collaboration with the labour market

These factors concern the regulation, organisation, and delivery of training, as well as the prioritisation of how synergies between both formal and non-formal language training and language training and the labour market. While all stakeholders seem to consider these factors important, which quality factors that are considered especially important depend on the stakeholder perspectives. For example, providers are more concerned with how compensation models and procurements systems affect the quality of training, whereas participants are more concerned with how training is organised and delivered.

While the study has found some minor differences between immigrant sub-groups when it comes to motivations for participation and barriers to achieving goals, differences when it comes to how quality is perceived are less prevalent. While individual circumstances influence the degree to which immigrants can participate in and make use of different types of services, all immigrants are affected by factors such as teaching skills, didactic methods adapted to their needs, group composition and learning environments and the extent to which training is meaningful. However, immigrants with resources such as time, study techniques and a high level of education are more likely to achieve their goals, even if the language training they participate in lacks quality, compared to groups with fewer resources. As such, a lack of quality in language training seems more likely to affect low-skilled immigrants negatively.

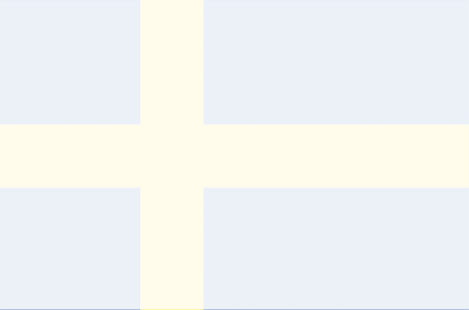

The identified quality factors are found to varying extents in the Nordic language training systems. Based on our findings in this study, Table 12 illustrates our assessment of how successful the Nordic countries are in delivering training that adheres to the quality factors. While Norway appears to have the most consistent quality in delivered training, Sweden seems to have the most challenges. The regulation and organisation of formal language training services, coupled with strategically organised funding for non-formal language training services, can be one explanation. It is also interesting to note that Norway is the country that has the highest average spending per participant in formal language training services, whilst Sweden has the lowest. Albeit spending is influenced by many factors not necessarily related to quality, this connection would be interesting to explore further.

DK | FI | NO | SE | |

Compensation models and procurement systems affect quality in a positive way |  |  |  |  |

Teachers are skilled and qualified |  |  |  |  |

Didactic methods are adapted to the needs of participants |  |  |  |  |

Learning groups have similar educational backgrounds |  |  |  |  |

Learning groups are small enough to facilitate learning |  |  |  |  |

Training is meaningful and relevant for participants |  |  |  |  |

Non-formal services effectively fill the gaps in formal services |  |  |  |  |

There is close collaboration with the labour market |  |  |  |  |

Table 12. Assessment of the extent to which Nordic countries have achieved identified quality factors

Compensation models and procurement systems affect the delivery of formal training both positively and negatively

While funding models for formal training differ between Nordic countries, the organisation of funding is perceived to affect the delivery and quality of training in two main ways. First, in relation to how language training services are compensated. Second, in relation to how language training services are procured. The extent to which funding models are considered to affect the quality of training do, however, differ between the Nordics.

As described in chapter 2.2, compensation models for providers in all Nordic countries but Norway are primarily based on participants completing the courses. Providers in both Finland and Norway consider their compensation models to have limited influence on the quality of formal training. Providers and employer organisations in Denmark and Sweden, however, point out that the compensation model based on course completion creates an incentive to prioritise costs over quality. In Denmark, where standardised testing is the norm, providers, teachers, and experts claim that classes have become more test oriented, meaning that teaching focuses more on the skills needed to pass the exams, rather than ensuring long-term language learning. In Sweden, the consequences are somewhat different. Here, participants and employers find that providers instead more likely to give participants a passing grade on a course, regardless of whether they have achieved the required proficiency goals.

The perception of the extent to which procurement models affect the quality of training also varies between the Nordics. In both Denmark and Sweden, where formal language training services are mainly procured through competitive bidding processes, municipalities are incentivised to choose providers which offer to deliver courses at the lowest cost. In Sweden, experts point out that this system may play a role in the uneven quality of services delivered. Denmark provides a more mixed picture. On the one hand, surveyed and interviewed providers in Denmark are critical to the current procurement processes, claiming that competitive bidding has pressured providers to cut prices by reducing the number of teaching hours for participants, increasing class sizes, and downgrading facilities, all of which have made it more difficult to recruit qualified teachers. On the other hand, a representative from a large municipality in Denmark maintains that evaluations show that competitive bidding has improved the quality and results of language training and increased its cost-efficiency.

Providers and stakeholders in Finland, largely consider the procurement process to be positive. They highlight that the process emphasises quality and while competition is stiff, it also ensures effectiveness. Nevertheless, providers also point out that there is a lack of funding in the system. This leads to teachers being underpaid and teaching facilities not being up to par. It also affects the possibilities to recruit new teachers.

Both Norway and some municipalities in Sweden use so-called authorisation systems to procure providers of formal training. Typically, these systems enable all providers which fulfil a set of criteria to provide training. In Norway, the system has limited the number of providers, ensuring that they adhere to high quality standards. In Sweden, the municipalities that use this system have instead found that it increases the number of providers, which affects quality both positively and negatively. Positively, since competition has forced providers to provide more topical and high-quality teaching. Negatively, since it makes long-term planning difficult when participants can switch providers at will. The increased number of providers has also made it more difficult for municipalities to monitor the quality of training.

Teaching skills and didactic methods adapted to the needs of participants

Two main factors related to teaching stand out as being particularly important for the perception of quality in language training among all stakeholders. The first concerns the skills and qualifications of the teachers who deliver the training. Qualified teachers can deliver higher quality teaching based on their training, experience, and pedagogical toolbox, compared to unqualified teachers. The second factor concerns didactical tools which can enhance the quality of training, particularly so-called authentic learning, and native-language teaching. Both teacher qualifications and didactical methods are particularly important to the quality of formal language training services, albeit they are also highly relevant to the non-formal traditional language training courses that many labour migrants participate in.

Surveyed participants consider teachers who adapt their teaching to the learning group or classroom situation, as well as enhancing participants’ understanding, to be the most quality important factors. The ability to make language learning sessions fun, creative, and engaging is also important.

Annex B: Figure B 4

Annex B: Figure B 9

Teaching qualifications are, however, not the only teaching-related factor that affects the quality of delivered training. The study shows that didactical methods also play an important role. Two methods stand out as being particularly important in language training for adult immigrants. First, experts and providers across the Nordics have highlighted the importance of promoting so-called authentic learning – teaching that is based on real-life situations that participants may encounter. While interviewed participants in all countries also appreciate teaching that places less emphasis on traditional classroom learning and more emphasis on how to use the language in their daily lives, this has especially been highlighted by interviewed participants in Finland and Norway. This is in line with survey findings, which show that participants consider “practicing conversation” to be an indicator of quality in both formal and non-formal language training,

Annex B: Figure B 4

Rambøll (2021)

Group composition and learning environments affect delivery

The organisation of language training affects the perceptions of quality in both formal and non-formal training. The main organisational aspects concern the composition of learning groups – particularly in formal training – and the learning environments.

When it comes to the composition of learning groups or classes, surveyed and interviewed providers maintain that learning groups that are heterogeneous in terms of language skills and educational background, make it difficult to deliver high-quality language training.

Annex B: Figure B 10

Unlike educational levels, heterogeneity in terms of native languages is not considered to be as considerable a challenge. Interviewed providers point out that there can be both advantages and disadvantages to teaching groups that are homogenous in terms of their native language. The positive aspects are that it makes it easier to compare grammar and syntax between their native language and the Nordic language. It also enables native language learning to a higher extent. However, providers also point out that groups that are too homogenous in terms of native languages risk falling back on their native languages to communicate between themselves, giving them less incentive to practice the Nordic language together.

Surveyed and interviewed providers and participants also consider large learning groups to have a negative effect on quality, since it makes it more difficult to give all participants an adequate level of attention.

Annex B: Figure B 11

When it comes to learning environments, interviewed providers in all countries highlight that a successful environment is where participants trust, support, and encourage each other within the group, and where the climate is open and accepting of mistakes. The survey also shows that providers across all countries consider a safe learning environment to be a necessary precondition for successful language learning.

Annex B: Figure B 12

Training is considered meaningful and relevant

Research shows that language training is most beneficial when participants consider it to be meaningful.

Pedersen, M. S. (2018)

One previously mentioned way to achieve meaningfulness in the delivery of language training services is authentic learning. Providers in all countries find it advantageous to connect teaching to society through projects and field trips, which helps participants experience the language and increase their understanding of its relevance to their daily lives. Providers from Norway and Finland point out that formal language training focuses too much on learning grammar through traditional classroom methods. They ascertain that it would be more beneficial to focus on subjects and themes that are important to participants, which could increase meaningfulness and further motivation. Providers in Denmark and Sweden also highlight the importance of basing teaching and discussions on concrete situations experienced by the participants, conversations about events in the Nordic country and native countries and specific challenges the participants may be facing. They also find that creative and physical activities can facilitate learning.

Non-formal language training services fill the gaps left by formal services

Different types of non-formal language training provide an important complement to formal language training services across the Nordics. As described in Chapter 2.3, broad variations in non-formal services mean that these services complement formal services in different ways. Across all countries and sub-groups of immigrants, non-formal language services are used to complement learning from formal language training, predominantly by providing opportunities for participants to practice the Nordic language and build networks. Non-formal language services also play a role in providing language training to immigrants who would otherwise be ineligible to participate, which is especially relevant in Finland, Norway, and to a lesser extent, Denmark. In Sweden, stakeholders consider non-formal services a crucial complement to a formal language training system where quality is uneven, filling the gaps where formal training has been unsuccessful.

74 percent of this study’s survey respondents have participated in non-formal language training services.

Annex B: Figure B2

52. Annex B: Figure B2

According to providers, non-formal services – especially those run by civil society actors – provide safe environments focused on building networks and increasing social integration rather than language learning. This is particularly beneficial for refugees and their family members, who are far from the labour market to a greater extent than other sub-groups of immigrants. A provider in Denmark explains how their meeting platform creates a network between participants, bringing them out of the isolation which often characterises immigrants who are far from the labour market. Through this, they can also help participants gain an understanding of the importance of learning Danish and encourage them to prioritise their participation in formal language training services. Another example from Denmark is Vestegnens Sprogcenter, a language centre that primarily offers formal language training services. Formal services are complemented by collaborating with volunteers, who help participants practice through a language café-like setting at the same location. Non-formal services can thus be important, not only in helping participants to learn and train the language, but also to understand their new country and facilitate their social integration.

A second way in which non-formal language training services complement formal language training services are by offering training to immigrants who are not eligible to participate in formal training. For immigrants who have never been eligible for formal training, specifically labour migrants in Finland and labour migrants from the EU/EEA in Norway, non-formal traditional language courses are one way of learning the language. Often, either participants or their employers must pay for these courses, which can be inhibiting. Typically, the teaching also encompasses substantially fewer hours than formal training.

Non-formal traditional courses can also be beneficial for immigrants who have previously been eligible for formal language training but have completed this without achieving adequate proficiency. A situation regularly found in Denmark, Finland, and Norway. Here, Norway’s previously mentioned subsidy for Norwegian education could be beneficial in ensuring that these immigrants can benefit from additional training. Other tools, such as the Lingio app can be used to strengthen language skills required for specific occupations. The app has been a useful tool to improve language proficiency among immigrants who have not achieved this through their formal language training in Sweden. Another example of such upskilling initiatives is the non-profit organisation MiR in Norway, which runs courses to improve the language proficiency of this specific target group (see Table 11).

A situation that seems to be exclusive to Sweden is that non-formal language training services are used to complement formal language training services which do not provide services of a high enough quality. According to interviewed non-formal providers and employer representatives, there is an ongoing debate as to the degree of responsibility that the non-formal sector should have in relation to the services offered. The interviewees are particularly adamant that non-formal services should not become a replacement for formal services, fearing that too much reliance is placed on them to fill the gap left by uneven quality in the formal language training system.

Close collaboration with the labour market

While language training is an essential part of the integration process, it is not always enough to ensure that immigrants are employable, which has been determined to be the most important goal of language training. Interviewed providers and employers ascertain that close collaboration with the labour market is important to ensure that language training does not take place in a vacuum. A labour market perspective can involve combining formal language training with VET that leads to qualifications in specific professions. It can also involve field trips, orientation courses, CV and job application workshops and other, less structured, connections to the labour market. Research from Norway shows how strengthening this connection can be an effective way to create meaning and motivation for language training, in that it can improve the participants’ opportunities to achieve their own employment goals.

Ideas2evidence (2020)

Providers in Finland highlight how combining language training with workplace-based experience can help enhance learning among those immigrants who learn better in practical environments than in classroom situations. All countries provide different ways to combine language training with VET (see Chapter 2.2). Providers in Sweden and Norway point out that combining language training with VET can be particularly useful for low-skilled immigrants with little or no education who often find it difficult to learn a language solely through a school setting. By combining learning with more practical skills, they are deemed more likely to succeed, both in their language learning and employment goals.

An employer organisation in Denmark points out that this type of training can be useful for immigrants who have completed their formal language training, but who have not found employment. These immigrants comprise the target group for this type of training in Denmark and Norway. In Denmark, the Basic integration education service (IGU) is specifically targeted at refugees and their family members – typically the sub-group with the lowest employment rates. However, an interviewed employer organisation in Sweden points out that combining language training and VET can be useful for all unemployed immigrants, regardless of their level of education. Jobs that require tertiary education often require a very high level of language proficiency for their employees, which may take several years to achieve. By learning a new occupation alongside language courses in Sweden, immigrants can enter the labour market, thus facilitating their integration and allowing them to develop their language skills in everyday situations, as well as allowing them to become self-sufficient.

Key takeaways

- The primary reason for immigrants to participate in language training identified in this study is labour market integration, both in terms of gaining employment and functioning in the workplace. Language skills are considered necessary to function in the workplace, as well as integrate socially.

- The main barrier to participating in language training is lack of time, particularly among labour migrants. Barriers to learning, on the other hand, are primarily a lack of social network and opportunities to practice as well as educational pre-requisites which affect immigrants’ abilities to learn and gain proficiency in a new language. An unevenness in the quality of delivered services also affects learning.

- The factors that are considered important to ensuring high-quality language training concern the regulation, organisation, and delivery of language training services. These quality factors encompass compensation models and procurement systems, teacher qualifications, didactic methods, composition of learning groups, and that training is considered meaningful and relevant.

- There are considerable synergies between formal and non-formal language training services, where the latter fill an important role in complementing the former. Non-formal services fill the gaps left by formal services due to lack of eligibility or low quality. They can also be beneficial in that they help immigrants to overcome barriers to language learning by being available at suitable times and creating social connections.

- Collaboration between formal language training services and the labour market is highly beneficial. Collaboration allows participants to become familiar with the labour market and potentially develop relevant vocational skills, but also to develop the more profession-specific set of language skills that is requested by employers.