INTRODUCTION

EU and Nordic countries are actively promoting the uptake of a circular economy with the expectation that a circular economy contributes to a regenerative growth model that lowers environmental impacts of carbon emissions, resource use, and land use while providing jobs and economic activity (EC, 2020 & Finnish Government, 2021).

The construction sector is throughout its entire value chain – from extraction, manufacturing, transport, and construction to end of life – responsible for half of all raw material extraction, 40% of energy use, 35% of CO2 -emissions and 25-30% of all waste produced (One planet network, 2020). A circular transformation offers a pathway to lower carbon emissions and resource use of the sector while limiting the negative environmental impact of construction and demolition waste.

Monitoring the circular performance is critical to accelerating the progress towards a circular construction sector. It can deliver knowledge of challenges, inform how far the Nordic countries are from realising specific circularity targets, and strengthen initiatives. Nevertheless, monitoring the circular transformation of the construction sector is currently dispersed. Moreover, the national Nordic circular economy strategies and monitoring frameworks in the construction sector are diverse in substance and scope (Castell-Rüdenhausen et al., 2021).

The challenge of measuring the circular economy has received much attention in recent years. Various methods have generated indicators and metrics for circular economy strategies beyond reuse, recycling, and recovery. The recognised 10R framework expands the EU waste hierarchy and introduces ten circular strategies within the circular economy umbrella term (EEA 2021).

- Refuse (R0)

- Rethink (R1)

- Reduce (R2)

- Reuse (R3)

- Repair (R4)

- Refurbish (R5)

- Remanufacture (R6)

- Repurpose (R7)

- Recycling (R8)

- Recover energy (R9).

Especially the first eight (R0 – R7) strategies can contribute significantly to making the EU more circular, but our study indicates that research, monitoring, and policy targets are currently focusing mainly on R8 and R9. The need for better monitoring of circular construction is widely accepted, but it is not clear how to establish feasible monitoring frameworks that cover the most promising circular strategies. Hence, the project is aiming to respond to three guiding questions.

- What should ideally be monitored in terms of circular construction,

- What do stakeholders find it important to monitor, and

- What can realistically be monitored across the Nordics.

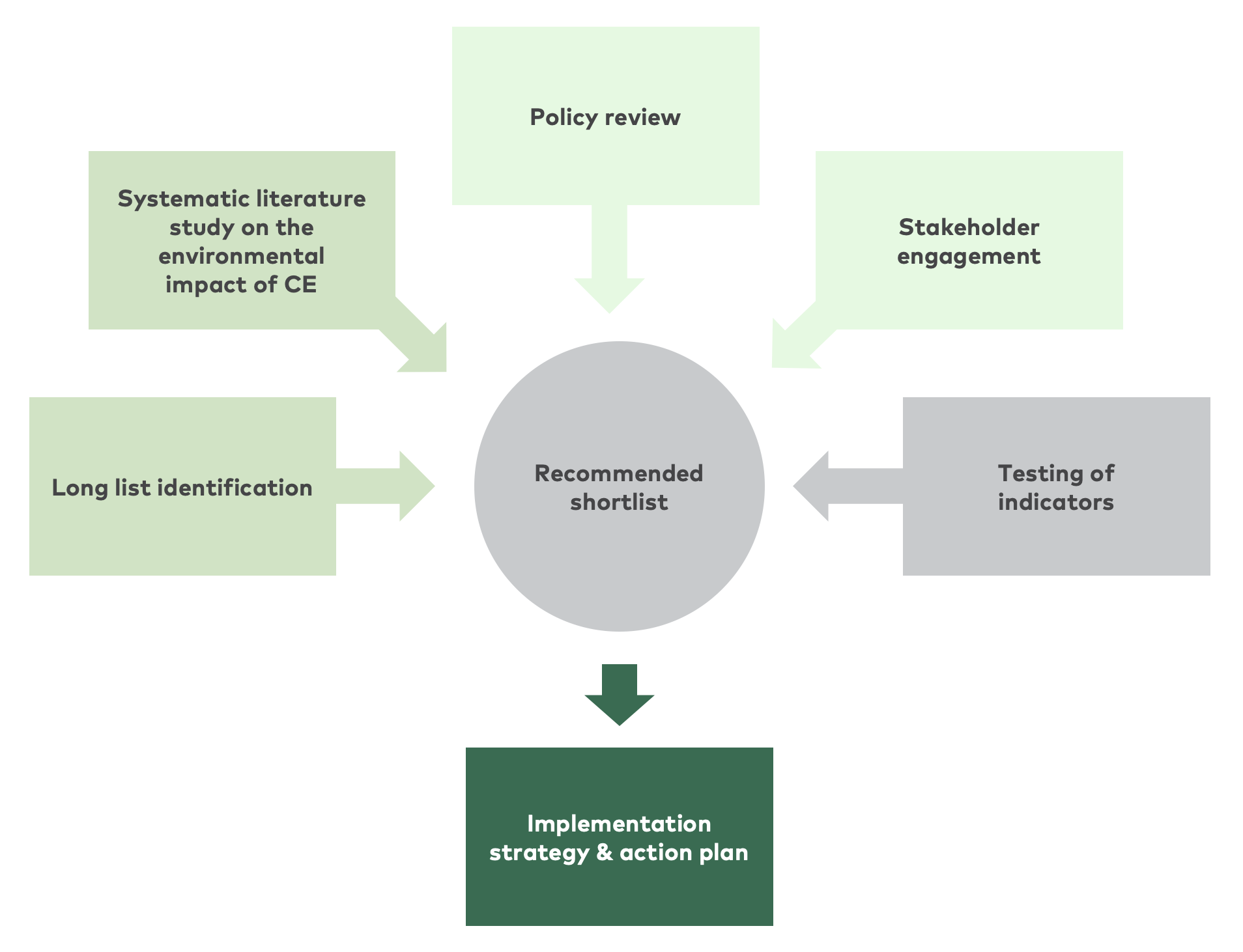

The project design, illustrated in Figure 1, reflects the guiding questions:

The WP3 project has delivered the following outputs, which are summarised in the present report.

- A long list of metrics for measuring circular construction (Norion, 2023a).

- An overview of European and Nordic policies, certification schemes and standards for circularity in construction (Norion, 2023b).

- An account of literature and research covering the relationship between the circular economy, biodiversity, ecosystems, and chemicals (Norion, 2023c).

- A shortlist of the most relevant indicators for circular construction (Norion, 2023d) and

A draft strategy for implementing the new monitoring framework for circular construction in the Nordics (Norion, 2023e).

The report is divided into three main chapters and three annexes:

The first chapter, HOW TO MEASURE CIRCULAR CONSTRUCTION, introduces a classification framework for breaking down ‘circular construction’ into concrete and measurable data points. Five categorial frameworks are combined to specify which circular economic strategies we are referring to, what time dimensions, which life cycle phases, what level of implementation, and what sustainability dimensions. Next, an overview of how the Nordic policy goals and targets are distributed across circular economic themes is presented. Eighty-six circular construction policy targets are identified and grouped, and the policy focus is compared across the Nordics to establish an overall objective to monitor progress. The chapter also discusses the role of certification schemes in monitoring the circular properties of buildings.

Chapter two, PRIORITISED INDICATORS FOR CIRCULAR CONSTRUCTION, presents the suggested shortlist of eleven prioritised indicators. Each indicator is elaborated, discussing potential metrics, the added value to the Nordics, and existing data points.

Finally, chapter three, DRAFT STRATEGY FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NEW MONITORING FRAMEWORK, suggest an implementation pathway for the prioritised indicators in the Nordics.

Some of the processes that have led to the suggested shortlist are described in the annexes.

Annexe 1, STAKEHOLDER INTERESTS, describes feedback received on the suggested monitoring framework within the project during project workshops and interviews. Annexe 2, LINKAGES BETWEEN CIRCULAR ECONOMY, BIODIVERSITY, ECOSYSTEMS, AND CHEMICALS, explores peer-reviewed literature on the connection between circular construction and its environmental effect. Despite several research gaps, the review highlights some critical trade-offs that policymakers must consider when implementing circular economic strategies. Finally, Annex 3, LONGLIST OF INDICATORS, elaborates on screening literature and existing frameworks for possible indicators and proxies for circular construction. The longlist is also included, although without the classifications of the indicators.