3. A framework to understand barriers to employment

The aim of this chapter is to identify important barriers to employment for vulnerable groups in the Nordic countries, including common barriers across the traditional target groups, and to estalish a framework of barriers that will provide a usefull grid for understandig different types of barriers and their potential interaction.

3.1 Overview of identified barriers

In the previous chapter, we described how we have defined barriers to employment and how we have identified these barriers in the Nordic literature. In this section, we try to draw conclusions across the Nordic literature reviews.

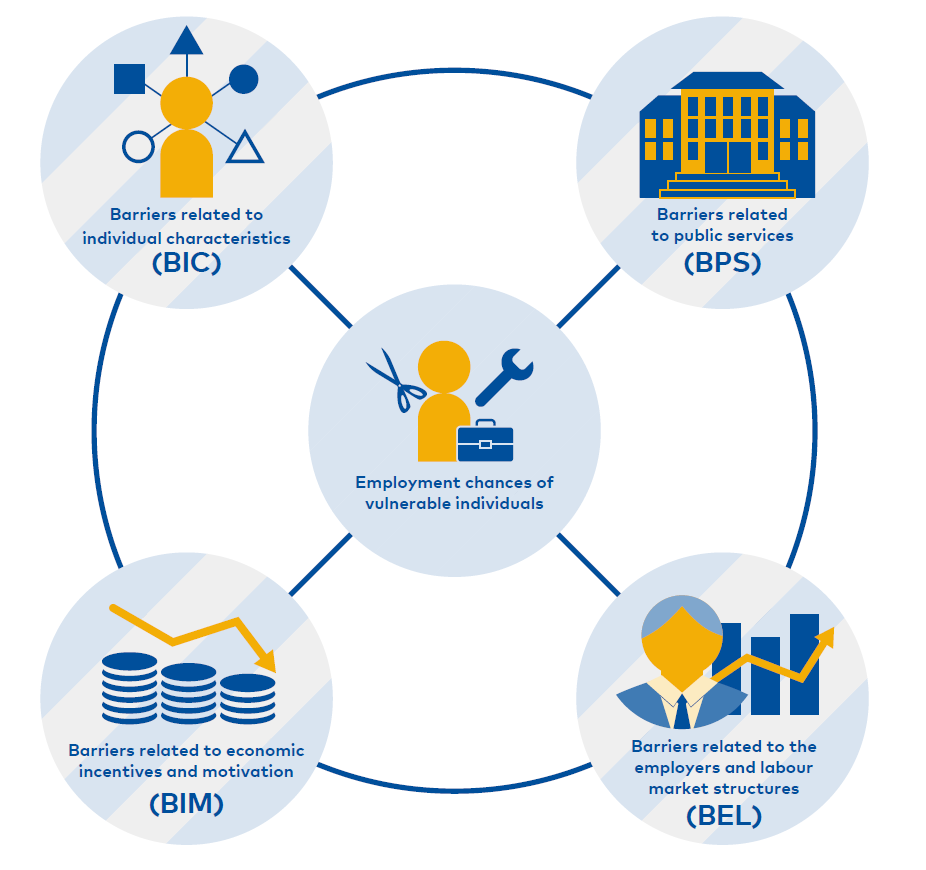

As mentioned in the previous section, we have identified more than 100 employment barriers, which we have categorised into 24 distinct barriers related to either individual characteristics (BIC), economic incentives and motivation (BIM), the employer and labour market structures (BEL), or public services (BPS). This framework gives an extensive overview of the employment barriers faced by vulnerable groups in the Nordic countries.

Framework over employment barriers for vulnerable groups

In this section, we will briefly present the framework over employment barriers for vulnerable groups in the Nordic countries. The framework is presented in figure 3.1 and shows the 4 categories of barriers and the 24 unique employment barriers that have been identified in the extensive Nordic literature review. The framework illustrates that we have identified 8 barriers related to individual characteristics, 4 barriers related to economic incentives and motivation, 6 barriers related to the employers and the labour market structures and 6 barriers related to public services. The framework is based on more than 80 academic references, in which more than 100 employment barriers have been identified. It provides an extensive overview over employment barriers vulnerable groups in the Nordic countries face based on the most recent research.

Figure 3.1 Framework over employment barriers for vulnerable groups in the Nordic countries

Note: This framework over employment barriers for vulnerable groups in the Nordic countries is based on an extensive literature review conducted by a panel of Nordic experts who all possess extensive knowledge on vulnerable groups and the barriers that these groups face.

Note: This framework over employment barriers for vulnerable groups in the Nordic countries is based on an extensive literature review conducted by a panel of Nordic experts who all possess extensive knowledge on vulnerable groups and the barriers that these groups face.

BIC

BIC1: Mental health issues

BIC2: Physical health issues

BIC3: Lack of relevant education

BIC4: Joint retirement

BIC4: Joint retirement

BIC5: Lack of language skills

BIC6: Lack of knowledge about the labour market

BIC7: Lack of work experience and skills

BIC8: Care responsibilities

BIC7: Lack of work experience and skills

BIC8: Care responsibilities

BPS

BPS1: Low effectiveness of public services

BPS2: Collision between public services

BPS3: Lack of participation in public employment services

BPS4: Insufficient support for groups to overcome other barriers

BPS5: Lack of resources

BPS6: Regional differences in service provision and access to services

BPS6: Regional differences in service provision and access to services

BIM

BIM1: Insufficient economic incentive to find education/ employment

BIM2: Retirement and pension benefits, incl. early retirement and sick pay

BIM3: Mismatch between job content and personal values

BIM4: Lack of motivation

BEL

BEL1: Costs associated with low productivity

BEL2: Information gaps and risks related to hiring employees

BEL3: Discrimination

BEL4: Working econditions

BEL4: Working econditions

BEL5: Lack of local employment opportunitites

BEL6: State of the economy

BEL6: State of the economy

Relevant barriers for each target group

In this subsection, we will highlight relevant barriers found in our literature review for the four traditional target groups. Table 3.1 shows the prevalence of each of the 24 barriers from the Nordic literature review. An X indicates that the barrier was identified for the target group in one of the Nordic countries.

For young people, we have identified 10 specific employment barriers. For instance, mental health issues (BIC1), either minor emotional barriers (e.g., mild anxiety) or major mental illnesses (e.g., schizophrenia or severe depression), which must be handled in order to find and fulfil employment are identified as a barrier. Vulnerable young individuals typically also lack relevant education (BIC3), while the social security systems in the Nordic countries can also cause the group to have insufficient economic incentives to find education/employment (BIM1) due to high outside options. Finally, low effectiveness of public employment services (BPS1) due to e.g., a lack of integration between education and employment services is also a prevalent barrier for the group.

Barriers to employment for seniors not only prevent unemployed seniors from finding employment but also potentially push some employed seniors into retirement. In this targeted literature review we have identified 12 barriers to employment relating to seniors (covering both barriers/factors affecting entry into the labour market and exit from the labour market). For example, physical health issues (BIC2) such as disease and pain, low work ability, and general poor health are all examples of an important employment barrier among seniors. This barrier is a push factor for retirement. Another push factor for retirement is a poor/unhealthy working environment (BEL4). Besides push factors, there are also pull factors, which are conditions outside the labour market that make it more attractive to retire than to stay in the labour market. One pull factor we have identified consists in economic factors such as retirement and pension benefits (BIM2) since these, in some instances, decrease seniors’ economic incentive to stay on the labour market before the official retirement age.

Our findings relating to seniors highlight that often it is relevant to distinguish between barriers (factors) affecting entry into the labour market and barriers (factors) affecting exit from the labour market. Often studies pertaining to senior’s employment barriers focus on the latter type, while many studies relevant to the other three target groups focus on barriers to labour market entry.

Table 3.1 Overview of barriers related to employment across target groups

BARRIER | YOUNG PEOPLE | SENIORS | IMMIGRANTS | PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES | ||

Barriers related to individual characteristics (BIC) | BIC1 | Mental health issues | X | X | X | X |

BIC2 | Physical health issues | X | X | X | X | |

BIC3 | Lack of relevant education | X | X | X | X | |

BIC4 | Joint retirement | - | X | - | - | |

BIC5 | Lack of language skills | - | - | X | - | |

BIC6 | Lack of knowledge about the labour market | - | - | X | - | |

BIC7 | Lack of work experience and skills | X | - | X | X | |

BIC8 | Care responsibilities | - | - | X | - | |

Barriers related to economic incentives and motivation (BIM) | BIM1 | Insufficient economic incentive to find education/employment | X | X | X | X |

BIM2 | Retirement and pension benefits incl. early retirement and disability benefits | - | X | - | X | |

BIM3 | Mismatch between labour market and personal values | X | - | - | - | |

BIM4 | Lack of motivation | - | X | X | X | |

Barriers related to the employer and labour market structures (BEL) | BEL1 | Costs associated with low productivity | X | - | X | X |

BEL2 | Information gaps and risks related to hiring employees | - | X | - | X | |

BEL3 | Discrimination | - | X | X | X | |

BEL4 | Working conditions | - | X | - | - | |

BEL5 | Lack of local employment opportunities | - | - | - | X | |

BEL6 | State of the economy | - | - | X | - | |

Barriers related to public services (BPS) | BPS1 | Low effectiveness of public services | X | X | - | X |

BPS2 | Collision between public services | X | - | - | - | |

BPS3 | Lack of participation in public employment services | - | X | - | - | |

BPS4 | Insufficient support for groups to overcome other barriers | X | - | X | X | |

BPS5 | Lack of resources | - | - | - | X | |

BPS6 | Regional Differences in service provision and access to services | - | - | - | X |

Note: An X means that the barrier was identified for the target group in at least one of the Nordic countries. The final framework of 24 barriers is based on a categorisation of more than 100 employment barriers found in literature reviews across the Nordic countries.

Table 3.1 also illustrates that for immigrants 13 employment barriers exist on the Nordic labour markets. For instance, lack of proficiency in the host country language (BIC5) is an employment barrier. Not being able to speak the common language in a country can exclude immigrants from certain types of jobs. Another barrier among immigrants is lack of working experience and skills (BIC7) demanded on the labour market in the host country. Moreover, immigrants face barriers related to discrimination (BEL3), e.g., experienced in relation to job applications, where individuals with foreign-sounding names have a lower probability of receiving an invitation for a job interview.

Among persons with disabilities, we have identified 15 employment barriers. For example, poor physical health (BIC2) may hinder them from participating in the labour market. However, the gravity of this barrier can vary depending on the type and severity of health problem. Another example of an employment barrier faced by persons with disabilities is retirement and pension benefits, including early retirement and disability benefits (BIM2). This can constitute a barrier to employment due to, for example, earning limits when receiving these benefits. Further, another example of an employment barrier among persons with disabilities in the Nordic countries is information gaps and risks related to hiring employees (BEL2), i.e. employers being risk averse in relation to hiring persons whom they fear will have long sickness absence periods resulting in discrimination against persons with disabilities.

Common barriers across target groups

In this subsection, based on Table 3.1, we will identify barriers that are common across the traditional target groups. We do so to demonstrate that it might be more relevant and effective to target policies towards individuals who face the same barriers than focus on their group affiliation (i.e., young people, seniors, immigrants, or persons with disabilities). To that aim, identifying barriers to employment that are relevant across target groups is important.

Table 3.1 shows that all the traditional target groups face barriers related to individual characteristics. For example, mental and physical health problems (BIC1 and BIC2) are barriers that are prevalent across the traditional target groups. All the four traditional target groups potentially experience barriers related to such conditions. Mental health barriers correlate with, e.g., poor well-being and difficult life situations that must be handled before participation in the job market becomes a possibility. Other common individual barriers are lack of relevant education (BIC3) and lack of work experience and skills (BIC7), which is a barrier shared among young people, immigrants, and persons with disabilities (and potentially some seniors who have been laid off and have difficulties finding a new job due to an obsolete skill set).

All the traditional target groups face barriers related to economic incentives and motivation. For example, all the groups face barriers related to insufficient economic incentives to find education/employment (BIM1). This is partially due to generous social welfare programmes and benefits, which provide a (relatively) attractive option for a non-work related income for individuals across all target groups in the Nordic countries. Besides the general social security benefits such as cash benefits, economic incentives from retirement and pension benefits (BIM2) constitute an important barrier to employment, though only for seniors and disabled individuals. Retirement benefits constitute a barrier that relates to leaving employment (before the retirement age) rather than entering employment. Further, several of the traditional target groups may lack motivation (BIM3) to enter employment, for example due to social norms among certain type of immigrants.

Table 3.1 also shows that several of the traditional target groups face barriers related to the employer and labour market structures. For example, young people, immigrants, and persons with disabilities all face barriers related to costs associated with low productivity (BEL1) from the employer’s perspective. Further, discrimination (BEL3) is also a specific barrier common across several target groups in the Nordic countries.

Lastly, Table 3.1 shows that public services offered in the Nordic countries also potentially harbour a number of barriers prevalent among the traditional target groups. For example, young people, immigrants, and persons with disabilities may face barriers related to insufficient support to overcome other barriers (BPS4). This, among other things, includes establishment support and coaching provided to newly arrived refugees as well as early detection and interventions regarding young people (especially school dropouts) who need support. Further, the effectiveness of the public services (BPS1) is another identified barrier, which is prevalent among young people, seniors, and persons with disabilities. It includes barriers such as poor collaboration between different public services and lack of common targets and approaches regarding the target group.

To sum up, table 3.1. shows that 12 of the 24 identified employment barriers are identified for at least two of the traditional target groups and among these 12, four are identified among all four traditional target groups. This highlights the potential of targeting policies towards individuals who face the same barriers, rather than focusing on their group affiliation. On the other hand, 12 barriers are only identified for one target group. Some of these 12 barriers may be prevalent for more than one target group, but only described in the included literature for one of the target groups. Other of these 12 barriers may be unique to one target group (for instance lack of language skills and joint retirement) demonstrating that policies tailored to address the specific challenges faced by each traditional target group are still relevant.

Concluding remarks

Based on the targeted literature review, we have identified 24 barriers. The literature review reveals that numerous barriers exist for each of the four vulnerable groups. For each of these groups, we have identified barriers related to all the four main categories of barriers, that is, barriers related to individual characteristics (BIC), economic incentives and motivation (BIM), the employer and labour market structures (BEL), and public services (BPS). The focus of the literature review was to obtain an overview of existing employment barriers for vulnerable groups, not to look at the coincidence and interaction between these barriers for the individual. However, the numerous barriers that each group of vulnerable persons potentially face indicate that often the barriers intertwine and may be mutually reinforcing. These indications are consistent with previous research (Benjaminsen et al., 2018; Frøyland, 2022; Andersen, 2017).

Moreover, the literature review shows that the barriers, typically, are not unique to one of the vulnerable groups but common across several groups. Some of the barriers identified in the literature for all four vulnerable groups are the following: mental health issues (BIC1), physical health issues (BIC2), lack of relevant education (BIC3), and insufficient economic incentive to find education/employment (BIM1).

Furthermore, the barriers do not seem to be unique for any Nordic country. Around two-thirds of the barriers listed in the previous section have been identified for at least two Nordic countries, and most or all of the described barriers probably do exist in all five countries. For instance, lack of employment opportunities (BEL5) only emerged in the included literature from Finland but is presumably also a barrier in the other Nordic countries – perhaps with differences in prevalence and underlying causes.

3.2 Description of the identified barriers

In this section, we describe the 24 identified barriers and use literature from one or several Nordic countries to explain each one. Note that the literature highlighted in this section should illustrate and provide an idea of what each barrier entails. Hence, the references presented are not authoritative research findings in terms of how we should understand each of the presented barriers.

Barriers related to individual characteristics (BIC)

Individual barriers are characterised as relating to personal decisions, health, skills, or qualifications. This can be lack of relevant human capital or barriers related to health issues. Moreover, this category covers behavioural barriers such as joint retirement. Below, we present the specific individual barriers we have identified in the literature reviews.

BIC1. Mental health issues: Mental problems can be related to personal issues, such as minor emotional barriers (e.g., mild anxiety) or major mental illnesses (e.g., schizophrenia or severe depression), and these conditions must be handled before it is possible to search for work or fulfil a job. For example, researchers from Denmark have found that mental health issues correlate with unemployment for young people (Andersen, 2017). Further, researchers from Finland have found that persons with a mental disorder followed less favourable work participation trajectories around vocational rehabilitation compared to individuals with other diagnoses (Leinonen et al., 2019). In a research report from Denmark, ill health and insufficient coping with ill health (e.g., mental health issues) are also shown to constitute a potential barrier for unemployed non-Western immigrants; however, according to the report, this barrier is not the most important one for this target group. Among other things, the report uses survey data on case workers who work professionally with this group. Therefore, the barrier is not observed directly for this target group (Jakobsen et al., 2021). For seniors, Swedish research points to personal factors related to health (such as psychological health disabilities) as potentially pushing some seniors into retirement (Jonsson, 2021).

BIC2. Physical health issues: Physical limitations can be a barrier to participating in the labour market. A large literature review conducted by Danish researchers on Nordic literature and to some extent literature from other Western countries shows that the severity of a disability is a crucial factor affecting labour force participation. This is based on several studies finding that persons with minor (self-rated) disabilities have an employment rate that is almost on the same level as persons with no disabilities, while persons with major (self-rated) disabilities experience much lower employment rates compared to persons with no disabilities (Bredgaard & Shamshiri-Pedersen, 2018). Another Danish study, based on a representative survey of Danish individuals older than 51 years, demonstrates that poor health was an important determinant for retirement among seniors (Larsen & Amilon, 2019). Swedish research on school-to-work transition among young people shows that young people with health problems or some type of disability have lower employment rates compared to young people without any health issues or disabilities (Engdahl & Forslund, 2015). Lastly, research from Denmark (also referred to above) demonstrates that ill health and insufficient coping with ill health – mental as well as physical health issues – can potentially be an employment barrier for unemployed non-Western immigrants (Jakobsen et al., 2021).

BIC3. Lack of relevant education: Lack of education can cause difficulty with finding employment in different ways and for different target groups. In this targeted literature review, lack of relevant education has been found to be a barrier for all the traditional target groups. For example, a study from Norway uses administrative data from 2002 to 2017 on disabled young individuals (i.e., persons below 29 years who have been granted disability benefits) to show that fewer disabled young people complete compulsory education compared to earlier, highlighting a potential barrier to employment for this group (Bråten & Sten-Gahmberg, 2022). Research from Finland shows that seniors with higher education retired later than individuals with lower education, which among other things could indicate that seniors with lower education risk early retirement due to a lack of relevant education (Nivalainen, 2022). A descriptive analysis from Norway, based on administrative data and extrapolations, points to the fact that Norway will experience an increased number of older immigrants over the coming two decades. These immigrants are expected to lack higher education and hence are likely to experience lower labour force participation rates (Tønnessen & Syse, 2021). Moreover, immigrants may have education from their country of origin that is useless or not recognised in the new host country’s labour market (Schultz-Nielsen & Skaksen, 2017). Finally, an extensive literature review from Denmark shows that the level of education has gone up during the latest ten years among persons with disabilities. Still, persisting low levels of education among some persons with disabilities constitute a barrier to increasing their employment chances (Bredgaard & Shamshiri-Pedersen, 2018).

BIC4. Joint retirement: A study from Finland finds that married persons are less likely to retire early in general. However, having a recently retired spouse can advance the retirement decision for the individual, the motivation being a wish to retire simultaneously as a couple. Similarly, having a non-retired spouse can postpone retirement (Nivalainen, 2022).

BIC5. Lack of language skills: Lack of proficiency in the host country language can prevent individuals from getting jobs. According to Swedish research, poor language skills decrease the likelihood of receiving an invitation for a job interview (Eriksson & Rooth, 2022). Further, Danish research uses an internet-based survey among managers and employees in Danish job centres to show that lack of language skills is a relatively important employment barrier (according to the survey respondents) for unemployed non-Western immigrants (Jakobsen et al., 2021).

BIC6. Lack of knowledge about the labour market: For unemployed citizens, lack of knowledge about the labour market can be barrier to employment. Danish research on non-Western immigrants in Danish municipalities shows that lack of knowledge about the Danish labour market is an important barrier to employment among newly arrived female immigrants, typically refugees and persons reunited with their families (Jakobsen et al., 2021).

BIC7. Lack of working experience and skills: Having little or no working experience and/or a lack of skills can be a barrier to employment. Among immigrants in Finland, lacking work experience is a hindrance to employment. Therefore, the period immediately after immigration seems crucial for accumulating work experience in the host country (Busk & Jauhiainen, 2021). Further, Norwegian researchers have used administrative data and a quasi-experimental design to show that lack of qualifications and skills negatively affect the employment opportunities among young people with mental health problems (Markussen & Røed, 2020).

BIC8. Care responsibilities: Some individuals face difficulties in participating in the labour market due to their responsibilities for taking care of children or elderly relatives. Most likely, this is a smaller barrier to employment in the Nordic countries today compared to e.g., Southern Europe, due to the fact that responsibilities formerly considered to be familial are now managed, to a relatively large extent, by the Nordic welfare states. Nevertheless, research conducted in Finland has indicated that such responsibilities do pose an employment barrier, particularly for immigrant women, who are more likely to stay home for longer periods following childbirth (Tervola, 2020; Busk & Jauhiainen, 2021). Moreover, the persisting gender employment rate differences in all the Nordic countries (i.e., men being employed to a higher extent than women are) might also be due to, inter alia, gendered differences in societal expectations to care responsibilities.

Barriers related to incentives and motivation (BIM)

Barriers related to incentives and motivation cover, among other things, systems or benefits that provide an alternative to employment and affect the economic incentives to work. This can be through social security benefits or retirement and disability benefits as alternatives to work. This category further contains barriers related to the motivation of the individual, which can be governed by general or group-specific social norms.

BIM1. Insufficient economic incentive to find education/employment: Outside options, such as cash benefits systems, can prevent people from entering employment or push individuals out of employment. Based on the literature review, this seems to be an employment barrier for each of the four traditional target groups. First, research from Finland based on administrative data demonstrates that seniors increased their employment when extended unemployment benefits offered to seniors until retirement were postponed by two years from age 55 to age 57 (Kyvrä & Pesola, 2020). Second, researchers from Sweden use register data to show that large alternative income sources (such as unemployment benefits) decrease the likelihood of employment among immigrants in Sweden (Friedrich, Laun & Meghir, 2021). Third, in an analysis from the Danish Ministry of Children and Social Affairs on vulnerable young people, it is shown that decreasing the cash benefits for this group increases their employment (Børne- og Socialministeriet, 2016). Lastly, in an extensive but unsystematic international literature review from Norway, the authors hypothesised that generous health-related benefits combined with less generous unemployment benefits potentially lead to an increased number of persons on health-related benefits (Fevang, 2020).

BIM2. Retirement and pension benefits, incl. early retirement and disability benefits: Retirement and pension benefits provide an alternative way of generating income relatively to employment in a salaried job. This includes the lack of economic incentive to work due to receiving retirement benefits and alternative sources of pension benefits, such as early-retirement benefits. Research from Finland on persons with disabilities finds no relationship between the amount of disability pension and the probability of working among full-disability pensioners. However, partial-disability pensioners with average disability pension seemed to work more than comparable groups, which can be explained by the existing earnings limit affecting the probability of working while on a disability pension (Polvinen et al., 2018). Research from Norway on seniors provides another example of how economic incentives related to retirement benefits can be an employment barrier. This study shows that the effect of a retention bonus of 20,000 NOK reduced the probability of early retirement by 5.7 pct. (Hermansen & Midtsundstad, 2018).

BIM3. Mismatch between labour market and personal values: Differences between expectations in the labour market and personal values may constitute a barrier for some types of individuals. A study from Finland based on 28 interviews in one region in Finland examines why long-term unemployed young people give up their search for work. The researchers show that wage employment is not necessarily an important value for young people, and other aspects of life – such as leisure or other activities – may dominate in a period of a young person’s life (Ylisto, 2018).

BIM4. Lack of motivation: Lack of motivation constitutes a barrier since it may hinder individuals from entering employment, but it can also push people out of employment. Research from Finland shows that several key factors affect the retirement decisions of seniors, one of them being motivation (Nivalainen, 2022). Research from Denmark shows that older persons with disabilities have lower work motivation and lower employment rates than younger persons with disabilities (Bredgaard & Shamshiri-Pedersen, 2018). This is confirmed in research from Iceland, where persons with disabilities fear that they will not live up to the expectations and demands of the workplace, which discourages these individuals from searching for a job. This phenomenon is called internalised ableism (Júlíusdóttir et al., 2022).

Further, research from Denmark shows that lack of motivation may be a barrier for some immigrants, especially some newly arrived immigrant women. For these women, a low level of job motivation may stem from their origin in a different culture with different gender roles, where working outside one’s home and supporting oneself financially is perceived neither as women’s role nor as their responsibility (Jakobsen et al., 2021).

Further, research from Denmark shows that lack of motivation may be a barrier for some immigrants, especially some newly arrived immigrant women. For these women, a low level of job motivation may stem from their origin in a different culture with different gender roles, where working outside one’s home and supporting oneself financially is perceived neither as women’s role nor as their responsibility (Jakobsen et al., 2021).

Barriers related to the employer and labour market structures (BEL)

Barriers related to the employer and labour market structures relate to issues such as the hiring process, working environment, and work tasks, as well as (macro)-economic factors/business cycles and demand for labour that can affect the employment of the target groups.

BEL1. Costs associated with low productivity: Employers might experience high costs (wage, sick pay, annual leave, etc.) relative to the productivity that employees bring to a job. A Swedish study using combined register and survey data has found this to be a barrier for young individuals in Sweden (Saez, Schoefer & Seim, 2019). Further, another study from Sweden shows that persons with disabilities may experience difficulties finding employment due to the employer’s perception of their low work capacity relative to their relatively higher labour costs (due to, for example, needs for special adaptations of the work environment, instruments, etc.) (Angelov & Eliasson, 2018).

BEL2. Information gaps and risks related to hiring employees: It is important for employers to have access to realistic information about characteristics, productivity, and health restrictions of potential employees, such as those of people with minor disabilities, in order to make informed hiring decisions. Information gaps between employers and employees may lead to failed recruitments. In research from Finland, an electronic survey among employers is used to understand the recruitment of individuals with partial disabilities. The Finnish researchers identified the following barriers. 1) It is important for the employer to be provided with realistic information about the characteristics, productivity, and restrictions of people with partial work ability to support the recruitment process. 2) For employers in small companies, financial risks are a potential barrier due to the cost of absence, including sick pay and substitute personnel (Ala-Kauhaluoma et al., 2017). Another Finnish study, using survey data answered by employers, demonstrates that some employers are worried about several risks when considering hiring seniors (i.e., individuals older than 55 years). Some employers are concerned about the risk of sickness absence or the risk of a short remaining working life (Järnefelt et al., 2022).

BEL3. Discrimination: Several studies also demonstrate discrimination towards several of the traditional target groups (e.g., in the hiring process). For example, research from Denmark shows that individuals with a Middle Eastern-sounding name are less likely to be invited for a job interview (Dahl & Krog, 2018). Research from Finland and Iceland finds similar results, i.e., that job applicants with migrant background are less likely to receive a response from employers compared to applicants with ethnic majority names (Ahmad, 2020; Kristjánsson & Sigurðardóttir, 2019). In Finland, some persons with disabilities experience often being offered employment primarily through special arrangements, involving only a symbolic wage on top of their disability pension – something these individuals experience as discrimination (Hästbacka & Nygård, 2019). Discrimination against persons with disabilities is also identified as an employment barrier in Iceland. In this study, HR managers received CVs of individuals with the same qualifications but with different levels of mobility disabilities. Applicants with no disabilities were more likely to be hired than applicants with identical qualifications and some minor mobility disability (Júlíusdóttir et al., 2022).

BEL4. Working conditions: Having a stressful and physically demanding job can decrease the satisfaction of working and thus push people into unemployment. For example, research from Sweden has found an association between working time, dissatisfaction with working hours, challenging job requirements, and retirement age for seniors (Nilsson, 2020). Further, Danish researchers have shown that several work-related factors influence the planned retirement age. These factors include dissatisfaction with working hours, stressful work, and (lack of) influence on one’s own work situation (Amilon & Larsen, 2019).

BEL5. Lack of local employment opportunities: Geographical place of residence can affect employment through, e.g., fewer local employment opportunities. A study from Finland finds disabled individuals living in rural areas to have less work participation after vocational rehabilitation (Leinonen et al., 2019). Researchers have also found that lack of suitable work for people with minor disabilities and a reduced work capacity is a problem in large companies (Ala-Kauhaluoma et al., 2017).

BEL6. State of the economy: The state of the economy can be a barrier for a number of different reasons. For example, research from Finland demonstrates that the social and economic conditions during the year of immigration have a lasting impact on future working years for the immigrating individuals (Busk & Jauhiainen, 2021).

Barriers relating to public services (BPS)

This group of barriers relates to the effectiveness of the public employment services and other relevant services at state, regional, and municipal level. Moreover, we include barriers related to the use of the public employment services in this category.

BPS1. Low effectiveness of public services: Lack of collaboration between systems within the public employment services can pose a barrier to employment for certain groups. For example, Danish research points to problems in the municipal youth services relating to a lack of coherence and coordination among the many different institutions and actors involved in assisting vulnerable young people, even though these institutions (e.g., job centres and youth guidance departments) in many Danish municipalities are located in the same building. Further, this research highlights lack of common targets and approaches, lack of integrated IT systems, and lack of sufficiently early interventions as potential employment barriers that all result in low effectiveness of the public employment system (Bolvig et al., 2019). Cross-Nordic research underlines that insufficient coordination and integration across public authorities aiming at assisting vulnerable youth is a problem that exists in several Nordic countries (Frøyland et al., 2022). Moreover, Finnish research takes a qualitative approach to demonstrate that low effectiveness of the public services also constitutes an employment barrier for disabled persons in Finland. The interviewed individuals expressed that they, among other things, lacked knowledge regarding rights about services and that this was often further complicated by extensive bureaucracy (Hästbacka & Nygård, 2019). Another paper from Finland uses administrative data to show that seniors to a larger degree participated in services that have a low impact on later employment (Aho et al., 2018).

BPS2. Collision between public services: For young people specifically, research from Denmark finds that there can be a collision between the health professionals prioritising psychiatric treatment above employment and caseworkers in the job centre prioritising either education or employment over treatment related goal (Bolvig et al., 2019). A qualitative study covering Iceland, Faroe Islands, and the northern part of Norway confirms this finding. Hence, interviews with practitioners within the relevant welfare authorities in services for young people show, among other things, that the services typically exist in specialised silo organisations, something that limits their ability to attend to the complexity of problems characterizing this group (Anvik & Waldahl, 2017).

BPS3. Lack of participation in public employment systems: For the public services to make a difference and move people into employment, it is important that people use them. Research from Finland found that unemployed seniors (i.e., individuals older than 55 years) participated less in services and activation measures than younger individuals (Aho et al., 2018). The same pattern is found in Denmark. Seniortænketanken (2018) shows that the participation in active labour market programmes is slightly lower for seniors than for other age groups among unemployment benefit recipients. One explanation is that some groups, here seniors, get fewer offers from the public employment services. Another explanation is that some groups are not willing to participate in the activities offered by the public employment services (and succeed in avoiding participation) (Aho et al., 2018).

BPS4. Insufficient support for groups to overcome other barriers: In some instances, the public services offer insufficient support to some vulnerable groups to overcome barriers. For example, a Swedish discussion paper uses a Swedish reform as a natural experiment to demonstrate that establishment talks, individual plans, and coaching for newly arrived refugees increased the probability of employment. This highlights the fact that insufficient support can be an employment barrier for newly arrived refugees (Andersson Joona, Lanninger & Sundström, 2016). Further, a Swedish study on school-to-work transition for young people demonstrates that some young people (especially school dropouts at risk of ending up in the NEET group) require early detection if an offer of the support they need is to be successful. For example, according to the authors, this group could benefit from more employer-based, on-site training (Engdahl & Forslund, 2015). Further, research from Finland finds that lack of sensibility, understanding, and flexibility in disability services might be a potential employment barrier since such lack of understanding for an individual’s life situation may give rise to inadequate or insufficient help (Hästbacka & Nygård, 2019). Two other studies from Finland show that the lack of early identification of health and work ability problems can create a barrier to employment. Therefore, treatment of such problems among unemployed people would benefit from earlier detection in the public employment and health service systems (Laaksonen & Blomgren, 2020; Nurmela et al., 2020).

BPS5. Lack of resources: A study from Finland using qualitative interview data on persons with disabilities found that the Finnish disability services were seen as vulnerable by some of the interviewed individuals. This was due to the services constantly being managed with minimum staff and resources, which leads to outdrawn decision-making processes. Insufficient funding leads to insufficient service provision (Hästbacka & Nygård, 2019).

BPS6. Regional differences in service provision and access to services: Regional differences regarding both practices and the resources available can be an employment barrier for the individuals in the regions where the resources are low. This is found to be the case in a study from Finland regarding disabled individuals (Hästbacka & Nygård, 2019).