Introduction

Let us start by turning back the clock to mid-August 2019. In the aftermath of the attempted mosque attack in Baerum, Norway, by Philip Manshaus, an unusual political quarrel on the highest political level broke out between the Nordic countries. As Erna Solberg, the then Prime Minister of Norway, was asked about the status of right-wing extremism in Norway during the political week in Arendal, she stated, “When neo-Nazis march on Norwegian streets, both in Fredrikstad and in Kristiansand, you hear a lot of Swedish. Their [i.e., the Swedish, authors’ clarification] neo-Nazis are also trying to organize in the neighboring countries” (Dahl, 2019). The comment was not appreciated by then Swedish Minister of Energy and Transport Anders Ygeman, who first responded on Twitter, “If you govern with Fremskrittspartiet (often labeled as right-wing populists, authors’ remark) and appoint Sylvi Listhaug as minister twice, then maybe you should look at yourself in the mirror before glancing across the border” (Ygeman, 2019). Ygeman later developed the critique in media, stating, “We cannot escape the fact that two of the attacks (i.e., by Anders Bering Breivik and Philip Manshaus, authors’ clarification) we have seen have been carried out by Norwegians” (Söderlund, 2019).

The quarrel did not end there. The attacked Listhaug, Minister of Elderly and Public Health at the time and member of Fremskrittspartiet, responded the following day: “We do not take any advice from Sweden, which has a documented much larger neo-Nazi environment than Norway” (Svensson, 2019). Deeply worried about the heated exchange of words between the high-ranking politicians, the well-known Swedish commentator Oisín Cantwell from Aftonbladet suggested the quarrel to be “unworthy” and the politicians’ actions as “embarrassing” because “a Nordic joint effort is crucial in the fight against ideologically conditioned extremism in all its forms” (Cantwell, 2019).

The emotions seemed to have eased a bit the following week, and a more collaborative spirit emerged as Erna Solberg and former Prime Minister of Sweden, Stefan Löfven, met the press during a Nordic high-level meeting in Reykjavik. Löfven argued that the image of Swedish troubles with right-wing extremism spilling over to the other Nordic countries were wrong and that “all three (sic!) have this problem and that is why all three should collaborate” (TT, 21st of August 2019). Solberg elaborated on her previous comments and suggested that “the attacks in Norway had nothing to do with Sweden … but we observe how extremist groups in our countries collaborate and that we, which we have discussed today, must develop our collaboration further between our police agencies” (TT, 2019).

In line with the political quarrel, there have been developments in the right-wing extremism (RWE) milieu that suggest that RWE in the Nordic region is increasingly transnational in nature. The Soldiers of Odin emerged in Finland and later expanded to Sweden, Norway and beyond. The Nordic Resistance Movement emerged in Sweden and expanded to the rest of the Nordic countries. Stop Islamisation of Europe originated from the union of the Danish group Stop Islamisation of Denmark and English anti-Islam activists. Swedish activists are, moreover, instrumental to the growing movement referred to as the Identitarians. Finally, the terrorist attacks of Breivik have inspired extreme right activists elsewhere in the Nordics (e.g., Manshaus and the two school attacks in Eslöv and Kristianstad, Sweden). However, little research has hitherto been carried out on the pan-Nordic and transnational dimension of RWE in the Nordic region. Indeed, the literature on RWE in the Nordics either is outdated or lacking an analytical focus on this dimension of RWE.

Taken together, the political quarrel, recent developments in the RWE milieu, and the insufficient status of knowledge all point toward a need to invest in research on the pan-Nordic and transnational dimensions of RWE. Although we share the politicians’ opinion that more cooperation between the Nordic countries is needed, we also recognize that such a cooperation must be built on an existing body of knowledge about RWE and the prevention of RWE. This is what the present report is about: outlining what we know so that we are better equipped to meet future concerns.

In the next section, we define what we mean by RWE.

What do we mean by right-wing extremism?

“Right-wing extremism” is commonly used in the academic literature and media to congregate a disparate environment under one etiquette, and defining it remains a notorious problem. The common use of RWE in the media often comprises both nonviolent and violent actors, groups, and ideologies that operate on different arenas: parliamentarian, city streets, and, increasingly, digital realms.

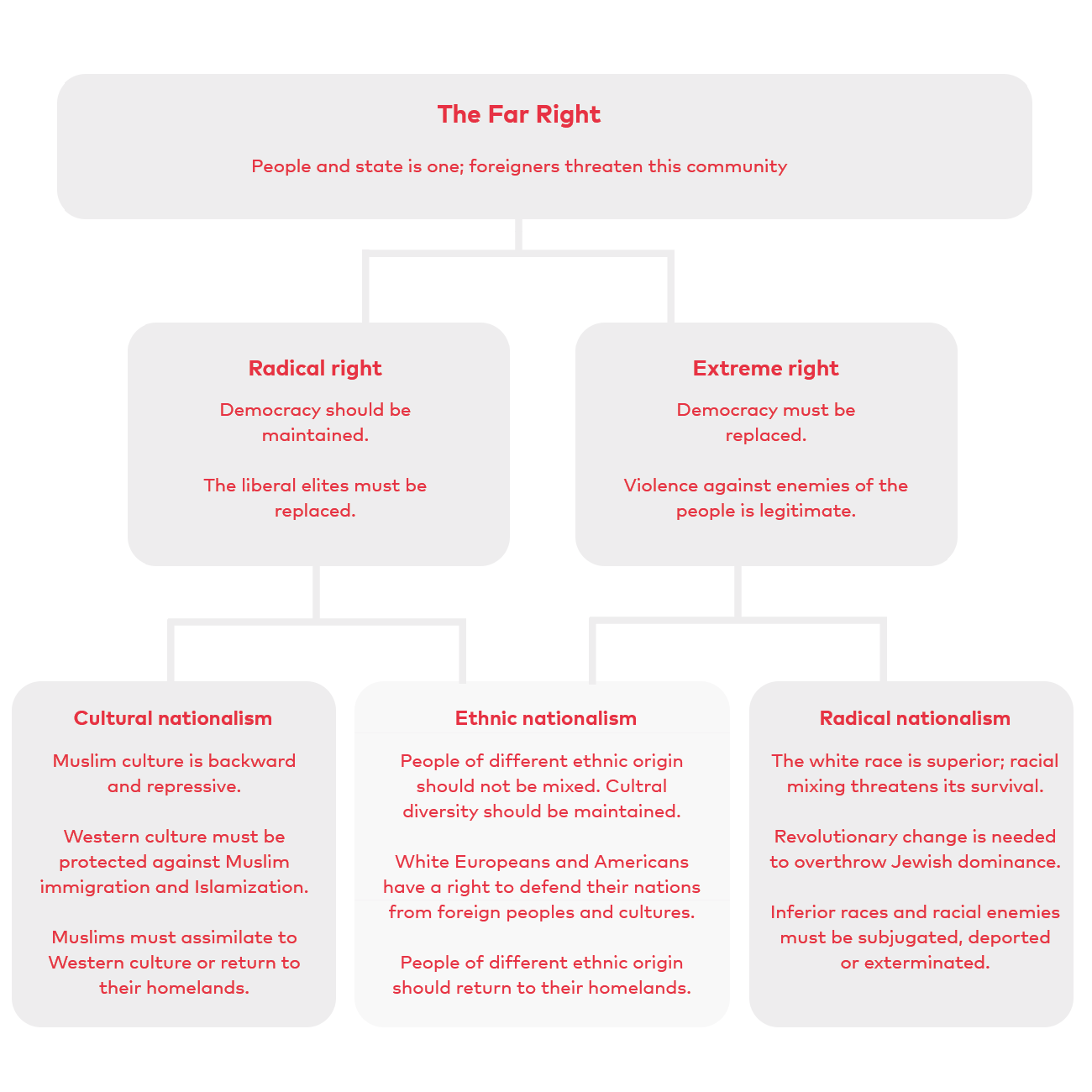

This type of broad definition of RWE is problematic. It lumps together two parts of the far-right milieu: (1) the radical right, here defined as anti-immigrant and nationalistic nonviolent actors who suggest democracy should be maintained and seek change within its premises, and (2) the extreme right, that is, explicitly racist and antisemitic violent actors who suggest democracy should be replaced and think violence is a legitimate means to achieve change (Bjørgo & Ravndal, 2019).

A family tree of the far right (Bjørgo & Ravndal, 2019; based on Berntzen, 2018; Mudde, 2002; Teitelbaum, 2017).

In relation to the family tree presented in the previous page, we focus on the extreme right and define RWE as a milieu which includes movements, organizations, and other actors that are authoritarian and/or anti-immigrant and exercise violence in rhetoric and/or practice. This will include more traditional national socialist groups, ethno-nationalistic movements, and so-called lone actors who share the same ideology.

Based on this definition, we now move on to give a short introduction of the type of threat that RWE poses for the Nordic countries, along with how it manifests itself organizationally.

Right-wing extremism in the Nordics

In the wake of the global “War on Terror” (Hodges, 2011), the potential deadly threat that RWE constitutes had been partially neglected. Historical data suggest, however, that such ignorance is misplaced. Ravndal (2018) has compared right-wing terrorism and militancy in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Between 1990 and 2015, a total of 141 events have been recorded. Of these, 89 took place in Sweden, 25 in Norway, 19 in Denmark, and eight in Finland. According to Ravndal (2018), there are indications of the Finnish dataset being flawed because of the lack of detailed information on further events in the 1990s and, to some extent, also the 2000s. As a more contemporary example of Finland not being spared from deadly RWE, a 28-year-old died in conjunction with an attack committed by an activist of the Nordic Resistance Movement (NMR) in 2016. Of the 141 events, 21 were deadly (17 in Sweden, three in Norway and one in Denmark). Between 1990 and 2015, the causalities of right-wing terrorism and militancy reached an aggregated number of 100 people (Ravndal, 2018). The most well-known incident of this kind is the Norway terror attacks of 22 July 2011, by Anders Bering Breivik. The attacks, which resulted in 77 dead, shocked not only Norway and the Nordic countries, but the world.

As in the previous mentioned cases of Manshaus and Breivik, most of the casualties have fallen victim to so-called “lone wolves” or, more precisely, “lone actors” in the right-wing milieu; these are individuals who are not formally organized and do not carry out their attacks in cooperation with others but rather perpetrate acts of violence alone while belonging to the same ideological milieu as other right-wing extremists (Gardell et al., 2017; Hemmingby & Bjørgo, 2016; Lööw, 2015). A contemporary characteristic of these actors is their preattack activity in digital, online right-wing environments that often feature a culture of glorification for terrorists and assailants (Kaati et al., 2019). The Swedes John Ausonius (shot 11 “nonwhites” and killed one between 1991 and 1992), Peter Mangs (attempted to kill 12 “nonwhites,” of which two died, between 2003 and 2010). and Anton Lundin Pettersson (killed three “nonwhites” in a school in 2015) can also be included in this category of lone actors. Other, more recurring forms of physical and psychological right-wing violence include harassment and death threats against political opponents, violent clashes between opposing groups, arson attacks on housing for refugees, the possession of illegal weapons, combat training, and the propagation of right-wing ideologies (Sivenbring & Andersson Malmros, 2019). The right-wing threat has transformed over time and so have the forms of violence. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Nordic countries faced a wave of murderous violence against LGBT persons, which peaked in the Gothenburg area (Lööw, 2004). Today, hate speech against the same group is still common, but the deadly violence seems, for the time being, less intensive. The same can be said of clashes between right-wing extremists and their violent opponents during rallies. Even if there are disturbances of order during rallies, the situation is less heated than some 20 years ago, allowing groups like the NMR to dominate street scenes.

Apart from lone actors, the RWE milieu is also organized into formal groups. Turning the clock back to the 1990s, the milieu was local, scattered, and fragmented (Bjørgo, 1997; Fangen, 2001; Lööw, 2000; Pekonen, 1999). The twenty-first century has seen a homogenization of the milieu’s organizational landscape, primarily through the NMR, but also as a result of increased interest in establishing and participating in the activities of alternative, less violence-prone right-wing political parties (Ravndal, 2018). Mattsson and Johansson (2019) described the NMR as the largest hub for neo-Nazis in the Nordic countries. The NMR is a traditional national socialist militant organization and party with roots that date back to the origins of the contemporary Nazi movement in Sweden (Mattsson, 2018). Originally named the Swedish Resistance Movement (SMR) at the time of its founding in 1997, the organization has gathered an increased number of violent and nonviolent activists. When Svenskarnas Parti (The Swedes’ Party) fell apart after the Swedish national elections of 2014, the SMR expanded their organization to include a parliamentary political party and announced themselves as being a “mass-movement of the Nordics,” hence forming the NMR (Lööw, 2017; Mattsson, 2018). Over the years, the NMR has included various national groups in Denmark, Norway, Finland, and Sweden who share the aim of establishing a common, racially homogeneous Nordic state. The NMR uses extensive online propaganda resources, primarily through their website Nordfront, to connect the Nordic milieu. News, activities report, podcasts, and interactive discussion forums are gathered and, to a varying degree, translated into the different Nordic languages. According to EXPO, a civil society organization that records all activities by the NMR and other similar organizations, 2018 saw a record number of 3,558 activities carried out by the NMR in Sweden. Even if the absolute majority of these activities were nonviolent, that year also witnessed an increase in physical manifestations and combat preparation activities (Expo, 2018).

More loosely organized and temporal types of social movements have also played—and continue to perform—a role in the RWE milieu. A contemporary example of this phenomenon are vigilante movements—organized civilians that act in a policing role without any legal authorization and use or display a capacity for violence (Bjørgo & Mares, 2019; Lööw, 2017). These movements and their activities often target migrants and minorities, here upon the premise that such categories of people are a source of crime. Kotonen (2019) tracked how one prominent example of such a movement, the Soldiers of Odin, that emerged in Finland in 2015 and became a Nordic and, partially, international phenomena gathering extreme right sympathizers and members. Bjørgo and Gjelsvik (2019) followed the milieu as it spread to Norway, where it rapidly collapsed because of ideological inconsistency and disagreements. Gardell (2019) focused on the digital milieu underpinning the establishment of the Soldiers of Odin in Sweden. He proposed that this “pop-up phenomenon” was linked to fake news in radical nationalist social media and their allegations of an ongoing “rape-jihad.” This aligns with the findings of Kaati et al. (2019) on the digital environments of the extreme right: that hate speech, conspiracy theories, and dehumanization are some of the methods utilized to assign traits to migrants and immigrants, thus making them legitimate targets of violence.

To summarize, the RWE in the Nordic countries is, at a closer look, a diverse one, despite the NMR dominating media attention. It consists of formal organizations such as the NMR, loosely coupled and temporal social movements that mobilize under certain conditions, and individuals and lone actors. The subcultural structure is still vivid and affluent, resulting in a crossflow of members between various organizations. RWE operates in different arenas; it has a strong digital platform on which propaganda, hate speech, and threats are distributed; it occupies the streets to recruit new members, combat its alleged enemies, and spread its ideological message; and, finally, it has made several attempts to gain support in the parliamentary arena. If successful, RWE would pose an ideological threat to the basic democratic ideas that underpin Nordic societies. The threat is, however, more obvious on the nonpolitical societal, group, and personal levels. Annually, the SOM institute measures Swedes’ level of concern over different phenomena, and their latest publication (SOM, 2019) showed a record level of 45% worried or very worried over political extremism. Among the groups targeted by right-wing terrorism, clear patterns have been occurring (Ravndal, 2018). Those most frequently targeted include immigrants (70 events), leftists (38 events), and homosexuals (nine events). Other targeted groups include government representatives, the police, Muslims, Jews, Gypsies/Roma, homeless people, and media institutions (Ravndal, 2018). According to national threat evaluations (see Sivenbring & Andersson Malmros, 2019), lone actors are increasingly seen as posing the greatest physical threat toward these groups.

In the next section, we outline the aim of the present report and the research questions guiding our activities within the project.

Aim and research questions

The overarching aim of the current report is to contribute with an up-to-date overview of the literature on pan-Nordic and transnational dimensions of RWE and describe how RWE has been prevented in the Nordic countries. More specifically, we explore the material (e.g., physical meetings, common demonstrations, and shared organizational structures) and cultural dimensions (i.e., shared ideologies and symbols) of the historical and contemporary pan-Nordic organizing of RWE, exploring what preventive measures have been deployed to prevent it. Although our focus is on the “pan-Nordicness” of RWE, we also consider other transnational connections, if found relevant. This knowledge can inform the requested cooperation on both the national and local administrative levels and new prevention strategies while strengthening Nordic collaboration on the issue.

We pose three questions that guide the report’s focus:

1. How transnational has the Nordic right-wing extremism milieu historically been?

The question is motivated by the fact that we lack an up-to-date overview of research exploring the historical dimension of the interconnectedness of RWE milieus in the Nordics (Lundström, 1983, is one of the few researchers to have explored the topic in his study on Nordic fascism). Even if research exists that includes descriptions of this interconnectedness, most studies have been carried out from a national-case perspective. Given the continuity and spatial stability of the milieus, to compile and review the existing historical research on a Nordic level would create an important outset for future research.

2. How pan-Nordic is contemporary right-wing extremism, and how is it connected to the global right-wing extremist milieu?

As part of the present report, we will also review the research on contemporary Nordic RWE, focusing on how it describes the interconnectedness of the milieu, along with how the Nordic milieu interacts with the global RWE milieu. Transnational activities are, as suggested by the introduction to section 2, an increasingly important component in contemporary RWE. An event on the 9th of November 2019 exemplifies the Nordic component of this environment. A coordinated action was conducted by the NMR where anti-Semitic symbols were posted on synagogues and Jewish community buildings in all Nordic countries during the commemoration of the November program. Paradoxically, at the same time as we see a pan-Nordic trend in the milieu, threats and violence are becoming increasingly “local.” Indeed, contemporary research and media reporting suggest that activists are, for example, targeting and abusing local politicians rather than national ones (Lööw, 2017). Surveys among Norwegian politicians in the parliament (Bjelland & Bjørgo, 2014; Bjørgo & Silkoset, 2017), for example, clearly indicate that threats from extremist individuals cause fear and disrupt their work as elected representatives, as well as their private lives. The fact that politicians are concerned about their own safety and that of their loved ones to the extent that they consider leaving or actually do leave their positions (e.g., Pierre Esbjörnsson in Skurup, Sweden, victim of a right-wing arson attack) is proof of extremism posing a serious threat to local democracy.

3. With what measures is right-wing extremism prevented in the Nordic countries?

There has been a long tradition in the Nordic countries to instruct schools, youth work and social welfare departments to prevent racism, bigotry and anti-Semitism and to encourage democratic attitudes. This has also included the prevention of recruitment to racist subcultures and RWE (Carlsson & Fangen, 2012; Mattsson, 2018). From the turn of the millennium, these efforts have been gradually incorporated into the prevention of violent extremism while still being partly understood as a task for schools and social welfare departments (Mattsson, 2018). Despite a lack of evidence-based evaluation on how to prevent violent extremism by the use of “soft measures” (Pistone et al., 2019), interventions to prevent RWE and racism are being carried out. Also, evaluations of these exist, even if they do not meet the criteria for being evidence based. As part of this report, all prevention measures aimed at preventing RWE and racism that have been used for more than five years will be mapped and reviewed. Based on this effort, we will present suggestions for further research and policy recommendations based on existing research.

Based on the findings of activities 1–3, we will provide policy recommendations on how to prevent RWE and identify research gaps which need to be addressed.