Chapter 3

A stubborn stain? Occupational safety and health on cleaning platforms in Norway

3.1 Introduction

Throughout the past decade, a new form of work has emerged in the Nordic labour markets, in which isolated jobs are coordinated and distributed through digital platforms, commonly referred to as “platform work” (Valestrand and Oppegaard, 2022). So far, most research studies concerning platform work have focused on occupational groups like food couriers and taxi drivers operating for companies like Uber and Foodora. However, platforms are also emerging in the cleaning industry, although they have received comparably little attention (Wiesböck et al., 2023). Most cleaners who work for platform companies provide cleaning services in private households, and as most platform workers are self-employed, they generally work alone. Unlike food couriers and taxi drivers, these cleaners are therefore rarely noticeable on the streets (see Seppänen, Chapter 6). Thus, cleaners who work through digital platforms represent a spatially fragmented group, which poses challenges for trade unions and supervisory authorities, as well as for researchers who try to reach them (Wiesböck et al., 2023). These challenges are reflected in the insufficient data available concerning this occupational group.

Through a desk study and semi-structured interviews, this chapter investigates the working environment challenges that accompany digitalized work arrangements in the Norwegian cleaning industry. It raises questions concerning working environment challenges that differentiate platform cleaning from traditional cleaning and how these challenges appear and unfold in a market that is “unavailable” to most supervisory authorities. The platform company “Vaskehjelp” is used as the chapter’s main example as it is the largest platform company in the Norwegian cleaning industry.

3.2 The Norwegian cleaning industry

The cleaning industry is labour-intensive, with few requirements for formal education, high levels of turnover, and low costs of establishing a new business (Trygstad et al., 2018; Andersen et al., 2021). Until 2011, Norwegian authorities performed limited control checks in the industry due to a lack of regulations, making it particularly exposed to questionable actors looking to make “a quick buck”. For this reason, there have been many reports on social dumping and undeclared work in the past decades. The National Occupational Health Surveillance (NOA)

NOA is organized as a department at the National Institute of Occupational Health (STAMI) (NOA, n.d. b). NOA coordinates and systematises knowledge on the working environment and health for social partners, public authorities and stakeholders.

Several of the challenges that characterize the industry intensified after the EU enlargements in 2004 and 2007 (Andersen et al., 2016). Increased labour supply and lower wages made many businesses lower their prices for cleaning. This made it difficult for businesses that paid higher wages to compete. As the wage share of expenses is high, effectiveness and price are decidedly the most important competition parameters in the cleaning market (Trygstad et al., 2018). A distinction is commonly made between the “professional cleaning market” of professional customers in the public and the private sectors and the “private cleaning market”, which is the consumer market. This chapter is mainly concerned with the private market as platform companies primarily offer cleaning in private households.

3.2.1 Institutional changes

Due to the challenges in the industry, a tripartite sector programme was established in 2010 as a cooperation between the authorities and the social partners (Trygstad et al., 2018). The aim of introducing sector-specific programmes was to promote decent work in parts of the labour market that are characterized by circumstances such as low union densities, pressured wage and working conditions, challenges related to occupational safety and health (OSH) and large shares of foreign workers (Andersen et al., 2021). Participants in the sector programme cooperate on evaluating the need for new or adjusted measures to strengthen compliance with relevant regulations in the industry.

The low cost of establishing a new business, and the strong increase in labour supply from new EU Member States, resulted in price pressure and challenges for the parts of the industry that were not covered by collective agreements (Jordfald and Svarstad, 2020). Other trends, such as a high turnover rate and the high proportion of immigrants having their first encounter with the Norwegian labour market, eventually led the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO) to require a general application of the industry’s collective agreement (ibid.). This requirement was supported by the Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise (NHO), representing the employers’ side. The Tariff Board, which holds the authority to generally apply collective agreements, granted LO’s request in 2011. This meant that all cleaning companies had to follow generally applied wage rates from the “cleaning agreement” (“Renholdsoverenskomsten”).

Between LO and the Norwegian Workers’ Union on the employee-side, and NHO and the Norwegian Federation of Service Industries and retail representing the employer-side.

The cleaning agreement

The generally applied collective agreement states that the hourly minimum wage in the cleaning industry is NOK 216.04, or NOK 165.05 for employees under the age of 18 years (Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority, 2023). The agreement also includes requirements for employers to supply employees with the necessary personal equipment, such as workwear and shoes (Valestrand & Oppegaard, 2022). The customer is obliged to ensure that the supplier fulfils the generally applied terms. The general application does not cover self-employed workers, as they are not classified as employees and therefore not part of the collective agreement. Still, generally applied collective agreements have traditionally had a norm-creating effect on the labour market (Alsos & Eldring, 2015). This also means that these agreements can place economic pressure on companies who use self-employed workers, making it difficult to recruit workers if they pay worse than their competitors.

The generally applied collective agreement states that the hourly minimum wage in the cleaning industry is NOK 216.04, or NOK 165.05 for employees under the age of 18 years (Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority, 2023). The agreement also includes requirements for employers to supply employees with the necessary personal equipment, such as workwear and shoes (Valestrand & Oppegaard, 2022). The customer is obliged to ensure that the supplier fulfils the generally applied terms. The general application does not cover self-employed workers, as they are not classified as employees and therefore not part of the collective agreement. Still, generally applied collective agreements have traditionally had a norm-creating effect on the labour market (Alsos & Eldring, 2015). This also means that these agreements can place economic pressure on companies who use self-employed workers, making it difficult to recruit workers if they pay worse than their competitors.

In 2012, an authorization scheme for cleaning companies was introduced, requiring all cleaning companies operating in Norway to be authorized by the Labour Inspection Authority (Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority, n.d.). The authorization process involves an application and documentation process through “Altinn”.

Altinn is an internet portal for digital dialogue between private individuals, public agencies, and businesses, as well as a technical platform for government bodies to develop digital services (Altinn, 2017).

The institutional changes that were implemented in the industry throughout this period, are closely linked to what is known as the Nordic model, which describes the ways in which the Nordic countries organize their welfare states and labour markets (Valestrand, 2023). The model is characterized by an active state, strong trade unions, welfare arrangements and coordinated wage determination. Valestrand (2023) argues that throughout the past decade, cleaning services coordinated through digital platforms have become part of the industry, but often outside of the traditional frame of the model, partly because platform workers generally are self-employed. This has great implications for workers’ social and labour rights, as self-employed workers are excluded from a number of labour rights and welfare systems traditional employees are entitled to (Jesnes, 2019). For instance, self-employed workers are not covered by the WEA, which governs most matters regarding occupational safety and health and welfare rights such as pension, taxes, unemployment benefits, parental leave and the like (Arbeidsmiljøloven, 2005).

3.2.2 Occupational safety and health in the cleaning industry

The cleaning industry is labour intense and characterized by time pressure, and the work pressure in the industry has been described as increasing (Trygstad et al., 2018). Nevertheless, NOA reports that of the 68,000 persons who work as cleaners in Norway, 51 percent are either unsure whether the enterprise they work for has an occupational health service

Occupational health services help employees and employers monitor the working environment within their company by providing professional consultancy services aimed at prevention efforts concerning health, safety and the environment (Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority, n.d. b).

In general, cleaners are at greater risk of skin ailments or diseases because their hands are in contact with water and chemicals for longer periods of time and they use airtight gloves (Trygstad et al., 2018). NOA reports that 74 percent of cleaners are exposed to contact with chemicals (NOA, n.d.). Furthermore, cleaners are among the occupational groups that are the most exposed to mechanical working environment factors such as heavy lifting, lifting in uncomfortable positions, working on the knees, or crouching, and working with their hands above their shoulders (Trygstad et al., 2018). NOA states that 48 percent of cleaners report neck and shoulder pain, with five out of six saying it is due to their work, and 49 percent report back pain, with five out of eight reporting that it is due to their work (NOA, n.d.).

Cleaners generally perform their work separately from the enterprise they work for, and many cleaners start and finish their working day at the location of the customer (Trygstad et al., 2018). It is also common for cleaners to carry out their work for several customers at different locations on either a daily or weekly basis, and NOA reports that about 43 percent of all cleaners work alone (NOA, n.d.). As the location of the customer is where the cleaners spend most of their working hours, their work and working environment are highly influenced by the relationship between themselves and the customer. Trygstad et al. (2018) also point out that cleaners’ experience of their working environment will be influenced by the employer’s organization of the work, or the lack thereof.

3.2.3 Occupational safety and health in platform cleaning

On behalf of EU OSHA,

The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work.

Lenaerts et al. (2022) also problematize how the non-standard working arrangements that characterize platform work challenge the responsibility for OSH management of those providing the work (the platforms), the workers involved (the platform workers), and OSH professionals (such as safety representatives and labour inspectorates). Similarly, Kusk et al. (2022) emphasize how platform companies often present themselves as tech companies to avoid regulations within the industry they are entering, even though human supporters are facilitating the work. They carried out a qualitative study of platform workers’ perspectives on cleaning and food delivery platforms in a Danish context. One of their main arguments is that platform companies have, both rhetorically and practically, an interest in limiting the focus on the human aspects of the work, partly because it lets them avoid employer responsibility.

Wiesböck et al. (2023) have also researched domestic cleaners in the platform economy. Like Kusk et al. (2022), they argue that platform companies do not act as neutral intermediaries or matchmakers but actively influence cleaners’ labour processes and opportunities through forms of control. Amongst other things, Wiesböck et al. (2023) find that the oversupply of cleaning profiles on digital platforms can lead to wage degradation, pressure to respond to requests immediately and a threat of being permanently replaced if workers are forced to cancel a job, for instance in cases of illness. Wiesböck et al. (2023) also shed light on the use of customer evaluations, arguing that customers are granted significant and lasting power to structure workers’ prospective job opportunities. Lenaerts et al. (2022) emphasize that maintaining a good rating, and dealing with the consequences of a bad rating, can cause significant stress for platform workers.

To summarize, previous research concerning occupational safety and health in platform work emphasizes the precarious employment conditions. The uncertainty regarding platform workers’ employment status creates an important OSH challenge: the ambiguity is closely linked to the question of who is responsible for the management of OSH – the workers, the platform, or the authorities? Despite this ambiguity, previous research has found that platforms and customers actively influence platform workers’ work processes through different forms of control. One way in which this control is performed, is through customer evaluations, which can place stress on the workers to maintain a good rating to secure requests from customers in the future.

3.3 Methodology

A desk study, existing literature and semi-structured interviews provide the empirical basis for this chapter. The desk study is described in closer detail in section 3.4. Altogether, I conducted eight interviews with a total of nine different interviewees. The interviewees included two representatives from a trade union organizing cleaners, a representative from the industry’s tripartite sector programme and a regional safety representative. In addition, the manager of a traditional cleaning company that offers its cleaning services digitally was also interviewed. Finally, I interviewed four cleaners: two worked as platform cleaners, one was employed in a smaller traditional cleaning company in the private cleaning market, and one was employed in a larger cleaning company in the professional market.

The choice to conduct semi-structured interviews was based on the notion that they would provide insight into how digitalized work arrangements are carried out in practice and what anticipated and unanticipated working environment challenges such arrangements may create in the cleaning industry. Semi-structured interviews also allow for a relatively structured analysis and comparison of the data that has been gathered. One of the interviews was conducted in person, two were conducted through video calls on Teams and the remaining five interviews were conducted over the phone. For the interviews carried out in person and through Teams, relatively similar interview guides were followed. These were slightly adjusted to each interviewee and their role. The guides included questions on the outreach of platform work in the industry, working conditions and wages, algorithmic management, OSH, the motivation for becoming a platform worker, representation, and prospects for the industry. This grouping of topics also provided the framework for the data analysis that followed.

As platform workers in the cleaning industry primarily offer cleaning services to private households, they do not have a set physical workplace. This makes them very difficult to reach – even more so than anticipated when the data collection was first initiated. The challenge of reaching cleaners prompted several methodological considerations. First, representatives of the social partners and the regional safety representatives were interviewed and asked whether they had communication with or links to any platform cleaners. Reaching platform workers through these interviewees proved very difficult. Most of them had great insight into the professional cleaning market but less into the private cleaning market and were quite distanced from cleaners who provide their services through digital platforms. Next, different cleaning companies were contacted directly. While the manager of one more traditional cleaning company agreed to participate, the platform companies did not have the time to participate in our research.

Some of the interviewees implied that the best way to get in contact with platform cleaners would be to book a cleaning appointment through one of the platform companies. I discussed this option with my colleagues but decided not to, based on ethical considerations. Spilda et al. (2022) recognize that platforms present a valuable tool for recruiting platform workers for research on the platform economy. Nonetheless, they emphasize that this recruitment approach presents important ethical concerns in terms of the workers’ anonymity, informed consent and the transparency of the research. In discussing this recruitment option, I found it particularly problematic that it would include ordering cleaning services to private homes and decided to be fully transparent with the cleaners throughout the entire recruitment process.

Finally, cleaners were contacted directly, although not through the platform. I studied cleaners’ profiles on Vaskehjelp, where they are presented with their full names, and used telephone directories to search for their phone numbers, subsequently contacting them directly through SMS. In these text messages, the cleaners were asked whether they would be willing to talk about their work for 20 to 30 minutes and were offered NOK 300 for their time. Out of the 16 cleaners that were contacted, three responded, and two were willing to participate in a telephone interview. As most cleaners work alone, the “snowball method”, where one informant leads you the next, was unsuccessful. For the two cleaners interviewed who did not work for a platform company, one was reached through a personal contact and the other through the trade union representatives that were interviewed in the beginning of the project.

3.4 Digital platforms in the cleaning industry: emergence and extent

In the desk study, the website proff.no

According to the service itself, Proff is the leading Nordic search and evaluation service for companies, official enterprise information, roles, and owners (Proff, n.d.).

NACE is a statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community (Eurostat, 2023). Traditional cleaning companies are typically registered as “81.210 Cleaning of buildings”, or “81.290 Other cleaning services”, while platform companies are commonly registered as “82.990 Other business services not listed elsewhere”, or even “62.010 Programming services”.

While the term “platform company” is ambiguous, it is used to describe companies with certain characteristics. To illustrate what distinguishes platform companies in the cleaning industry from traditional cleaning companies, Table 3.1 presents a simplified description of the characteristics of four forms of companies in the industry: a traditional cleaning company with employees, a self-employed cleaner who owns his or her own business, a platform company, and a hybrid cleaning company that uses digital arrangements for the communication and organization of the work yet employs the cleaners.

Table 3.1 Typology of cleaning companies and their characteristics.

Has employees | Uses self-employed workers | |

Traditional work arrangements | Traditional cleaning company providing cleaning services through employed cleaners. Cleaners are therefore covered by the WEA and the generally applied collective agreement. Provides services in both the professional and private cleaning markets. The company/employer is responsible for equipment and supplies for the job. | Self-employed cleaner owning his/her own business providing cleaning services to enterprises and private households. Cleaners are not covered by the WEA and the generally applied collective agreement. Provides services in both the professional and private cleaning markets but most prevalent in the private cleaning market. The cleaner or the customer is responsible for equipment and supplies for the job. |

Digital work arrangements | “Hybrid” cleaning company using digital arrangements for the communication and organization of the work yet employs the cleaners. Cleaners are therefore covered by the WEA and the generally applied collective agreement. Provides services in both the professional and private cleaning markets. The company/employer is responsible for equipment and supplies for the job. | Platform company: a “platform” for self-employed cleaners to get in contact with potential customers. Cleaners are not covered by the WEA and the generally applied collective agreement. Work is advertised and organized digitally. Primarily provides services in the private cleaning market. The use of customer reviews is widespread. The cleaner or the customer is responsible for equipment and supplies for the job. |

Through the desk study, five companies were identified as either “hybrid” or “platform” companies: Vaskehjelp, Maidme, and Luado are typical platform companies, while WeClean and Freska fit better into the hybrid category. One reason for this, is that the cleaners who work for WeClean and Freska are employees. The companies differ in size and reach, but mainly offer cleaning services in more urban areas as this is where both the supply and the demand are the highest. As mentioned in the introduction, Vaskehjelp is used as a case of a platform company in this chapter as it is the most established in the Norwegian cleaning industry. This makes the company, and the cleaners who work for it, the most accessible for research.

3.4.1 Vaskehjelp

Vaskehjelp has emerged as a new actor in the largest Norwegian cities, competing with traditional cleaning companies (Valestrand and Oppegaard, 2022). The company was established in Trondheim in 2016 as a platform for self-employed cleaners, mainly directed towards the private cleaning market. To request cleaning services, the customer types in the address where the cleaning is to take place and is presented with a selection of available cleaners in the area in question. Each cleaner’s profile includes a picture and a short description, an hourly price rate, reviews from previous customers and the number of jobs they have carried out for the company. To become a “Vaskehjelp cleaner”, a person must establish a sole proprietorship and receive an organization number, establish a Vaskehjelp profile in the app and apply for an HSE card from the Labour Inspection Authority (Vaskehjelp, n.d. a).

The number of available Vaskehjelp cleaners in different parts of the country and their hourly price range, experience with the company and gender distribution were mapped out through the desk study, which also gave an impression of their age and background. For instance, some cleaners wrote their profile presentations in English, and others in Norwegian. Some presentations were also quite detailed in terms of background information and previous experience. Table 3.2 provides an overview of the cleaners available

Here “available” implies all active profiles on the webpage, including the cleaners who are unavailable during the timeframe I have entered to reach the overview of the cleaners.

Table 3.2 Number of available cleaners divided by city, gender, and hourly price range (Vaskehjelp n.d. b).

City | Oslo | Bergen | Trondheim |

Number of available cleaners | 46 | 13 | 20 |

Hourly price range | 401 to 750 NOK | 399 to 749 NOK | 407 to 720 NOK |

Gender distribution | 41 women, four men | 13 women | 17 women, three men |

In the country’s three largest cities, I found 79 cleaners working for the platform. On the website, the customer can sort the profiles according to price and rating based on previous customers’ reviews. As the table illustrates, the range of price rates are quite similar in the three areas, although quite diversified within each area. While there are exceptions, cleaners who are new to the app and have fewer reviews and a lower number of previous jobs tend to offer cleaning services for a lower hourly price than cleaners who have longer experience. Cleaners who are new to the company are also labeled “new cleaner”, and the company often offers a price reduction to help these cleaners get their first customers. According to one of our interviewees who worked for the platform, these price reductions do not affect the cleaners’ wages.

The price the customer pays includes the cleaner’s honorarium, insurance, value-added tax, and maintenance of the app (Valestrand and Oppegaard, 2022). The platform company also takes a set percentage of the price for having put the cleaner and the customer in contact. The app is designed in such a way that the cleaner cannot offer cleaning services for a lower price than the generally applied minimum wage (NOK 216,04). The company pays the cleaners the sum of all jobs carried out minus the company’s share every other week. The payment takes place through the platform. Additional expenses, however, are not covered by the platform. As self-employed contractors, the cleaners carry costs such as the travel between jobs, workwear, their phones and the like, while the customer covers the costs of cleaning supplies and chemicals.

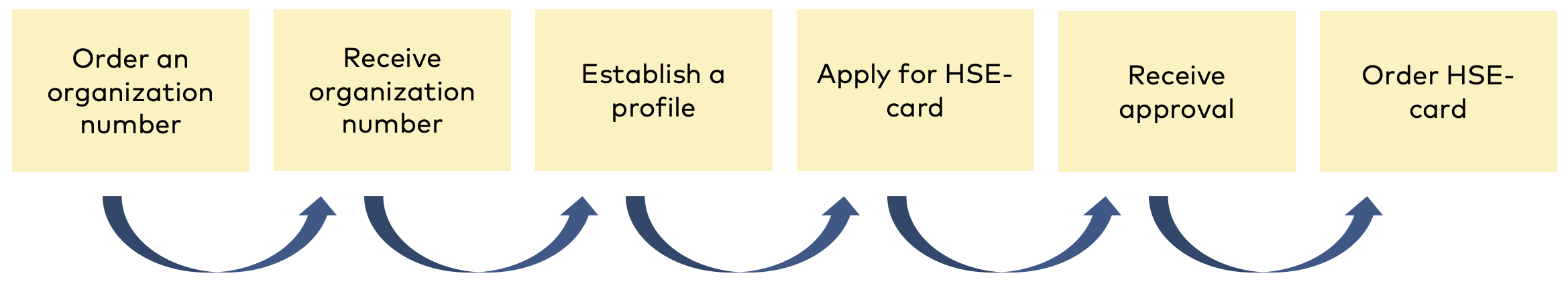

Through their webpage, Vaskehjelp also provides a guide on how to become a “Vaskehjelp cleaner”. This information is available in English and Norwegian and was previously displayed as a step-by-step overview with a timeline of how to become a cleaner and advertise one’s services through the platform. Figure 3.1 provides an overview of these steps.

Figure 3.1 How to become a Vaskehjelp cleaner step by step.

The platform estimates that the entire process could take anywhere from six to sixteen days. The webpage also used to have links to Altinn and to the HSE card application form. In late 2023/early 2024, the platform modified this information, and it now provides an overview of what a potential cleaner would need to do: (1) establish a sole proprietorship on Altinn to obtain an organization number, (2) create a cleaner profile in Vaskehjelp and (3) apply for an HSE card from the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority. Unlike before, the platform asks the cleaner to enter their full name and e-mail address to receive the step-by-step explanation.

3.5 Analysis: Platform work in the Norwegian cleaning industry

In this section, the empirical data is analysed and presented. First, we take a closer look at why cleaners choose to work for platform companies, followed by discussions of the platform companies’ employer responsibility, working environment challenges that characterize platform work in the cleaning industry, and authorities’ challenges in reaching this group of workers.

3.5.1 Why do cleaners want to work for platform companies?

Valestrand and Oppegaard (2022) argue that in a labour market that generally offers full-time positions, good working conditions and decent wages, one could expect that jobs with low and unstable income and long days, such as those available through platform work, become relatively less attractive. Nonetheless, they note that platforms have succeeded in getting a foothold in the labour market, partly by recruiting labour from the parts of the workforce that are often excluded from the stable and well-paid jobs that generally characterize the Norwegian labour market by offering formal flexibility, making the jobs more attractive than other work opportunities available to these groups.

This argument was supported by our interviewees from the trade union, the regional safety representatives, and the sector programme. They were of the impression that cleaners who take on jobs in the private cleaning market in general, and through platform companies in particular, do so because it is perceived as their only option. The representatives from the trade union were concerned that foreign workers might take these jobs without being aware of what they involve. They highlighted that these workers might not be familiar with the Norwegian language and the composition of the Norwegian labour market, adding that many cleaners are forced into sole proprietorships without necessarily knowing what it entails in terms of the instability and unpredictability of earnings and working hours, and worker and social rights.

In contrast, both of our interviewees who worked as cleaners for the platform company emphasized the positive sides of being a platform worker, and especially of being self-employed. The cleaners particularly valued the independence it allows and the opportunity the company provides as an arena – or a platform – to reach new customers. On of them said: “I started to use the app because I was curious. Maybe to be sure that I had some extra money. If my own customers are passing [me] over. I heard about the company from other girls (…) It is a very nice opportunity to get extra jobs” (cleaner, platform company). Another cleaner explained: “I like the independence at Vaskehjelp. I like that I don’t have any managers. No one to supervise me. I speak directly to the customer” (cleaner, platform company).

The advantage of having formal flexibility and autonomy as a platform worker is a central argument used by platform companies to recruit new workers (Valestrand and Oppegaard, 2022; Jesnes and Oppegaard, 2023). In sum, the cleaners I interviewed also pointed to these factors as important reasons for being platform cleaners. In addition, they emphasize the arena the platform provides for becoming visible and accessible to potential customers.

3.5.2 The legal responsibilities of the platform companies

Platform workers are often legally regarded as operating their own business, but as their services are mediated through, and to a certain extent managed by the platform, discussions have been raised concerning the amount of employer responsibility the platform should take on. Hotvedt (2020) argues that the allocation of responsibility in platform work raises difficult questions, considering that both the platform and the customers may, in certain cases and depending on legal interpretations, be responsible for employer duties. The regional safety representative I interviewed stated that one important measure to secure better working conditions for cleaners would be to place more responsibility on the platforms by clarifying the cleaners’ form of employment.

As described above, the cleaners I interviewed who worked for the platform company valued the flexibility and independence of being a platform worker. The cleaners are free to choose the area they want to work in, to set their own hourly rate, to decline requests from potential customers and to suggest a new time and date if the request does not fit their schedule. Despite this flexibility, one of the cleaners I interviewed also emphasized that the company does keep an eye on the cleaners and contacts them if they decline too many requests.

The cleaner had been contacted by the platform after choosing to be available for customers in a larger city centre after previously solely providing services in the city’s surrounding areas due to traffic and road tolls. When they became available in the city center, the number of requests they received rapidly increased, making the cleaner unable to take on all the proposed jobs. The platform then reached out, wanting to know the reasons for the decline in their job acceptance rate. After the cleaner explained the situation, the company showed understanding but also suggested limiting the cleaner’s availability in the city centre if the number of requests was too high, interfering with the cleaners’ opportunity to choose. Both interviewees who worked for the platform company also informed us that the platform covers the cleaners with an accident insurance. One of the cleaners also told us that the company provides the cleaners with a digital library of videos and courses for workers to consult as desired and is willing to help them with their taxes if they have questions.

As Wiesböck et al. (2023) point out, platforms actively influence cleaners’ labour processes, by monitoring declined jobs and interfering when the number of declined jobs is considered too high. The cleaners are classified as self-employed contractors and therefore not employed by the platform. However, the control performed by the platform affects the cleaners’ autonomy. In addition, the platform provides accident insurance and digital courses and ensures that the cleaners are paid the generally applied minimum wage, not counting expenses such as travel costs and workwear. The employer responsibility the platform takes on in terms of insurance and wage determination all point to the questions raised by Hotvedt (2020) concerning the extent to which the platform is responsible for the cleaners and their working environments.

3.5.3 Working environment challenges

In the following sections, we take a closer look at different working environment challenges that characterize work as a cleaner for platform companies. These include customer reviews, work pressure and time management and risks faced by self-employed workers in general. While self-employment is widespread among cleaners in the private cleaning market, it has significant implications for workers’ claim to social and labour rights. It must therefore be addressed in relation to other characteristics of platform work.

Customer reviews

On Vaskehjelp’s website, customers can sort the available cleaners according to their set hourly price rate and their customer reviews. The customer reviews are presented as the percentage of previous customers who have given the cleaner a “thumbs up” for the job they performed. According to the cleaners I interviewed, the platform asks the customers whether they would like to give the cleaner a thumbs up or not after the job is finished. On the website, you can also see the cleaners’ number of previous customers and the number of jobs they have performed. If you look more closely at each individual profile, you can also read reviews in cases where previous customers have left comments.

Both our interviewees who were platform workers informed us that they had not yet received any negative feedback from customers and noted that they were very happy about this. One of the cleaners was under the impression that most customers take the time to give a thumbs up, and many also give feedback through comments on the cleaners’ profiles. She added that if a cleaner rarely receives any feedback, their score will drop: “Some (customers) are silent and don’t write anything. I think your overall score will drop if you don’t maintain good feedback” (cleaner, platform company). Thus, these cleaners – like other platform workers (Wiesböck et al., 2023) – depend on customers’ good feedback to maintain a good score on their profile, which again affects their opportunity to receive more requests in the future.

One of the cleaners implied that the reviews make it easier for potential new customers to trust the cleaners and to let them into their private homes. Reviews can make the cleaners seem more trustworthy, and hence attract future customers. Likewise, a lack of reviews, or negative reviews, can make cleaners seem less trustworthy, highlighting their dependence on reviews. The cleaner added that the accident insurance provided by the platform also counts for this trust element as customers know that the platform will cover the accident if the cleaner breaks anything during a job.

Work pressure and time management

The cleaning industry is labour-intensive, and Trygstad et al. (2018) described the work pressure in the industry as increasing. One of the cleaners I interviewed emphasized that cleaning is heavy work: “It is difficult, physical work, and work under pressure” (cleaner, platform economy). The cleaners also placed an emphasis on the transit time between jobs. The cleaners I interviewed who worked for the platform were not paid extra on the weekends or for the transit time between jobs. The time it takes to get between jobs varies, and the cleaners emphasized taking this into account when planning and accepting jobs. As previously described, cleaners can decline jobs, or suggest a new date or time if the request does not fit their schedule. According to the cleaners, a cleaning job usually takes three to four hours but can last anything from two to six hours. Three hours is the “default” when ordering a “standard cleaning service” on Vaskehjelp’s website, but the customer can choose up to eight hours. The platform also suggests the time needed according to the size of the area the customer wants cleaned.

I asked the cleaners whether they felt stressed in their work, and both cleaners who worked through the platform answered that the work could be stressful but emphasized that being self-employed allowed them to manage their time as they please, which is helpful for stress management. One of the cleaners stated that she was not stressed but was working under pressure. Cleaners’ opportunity to manage their own time must be seen in light of the fact that it is the customer who decides the time frame. Both cleaners had experienced showing up at a customer’s house and realizing that the job would take longer than the customer had anticipated. As the cleaners plan their weeks based on these jobs, they are reliant on finishing a given job on time to reach their next customer. Furthermore, they are only paid for the time frame that has been set, and the reliance on customer reviews is an incentive to finish the job within this window. One of the cleaners put it like this: “The stress is only in my head, that I must do as much as possible to get a good review and so on. I think it is ok” (cleaner, platform company). In cases where cleaners need more time than the customer has anticipated, they can ask whether the customer would like to expand the time frame for extra payment or whether they can prioritize parts of the job to finish on time.

When asked about stress, one of the cleaners also emphasized that not having enough to do can be equally stressful as having too much to do. She expressed that she had felt more stressed when she was new to the platform, being concerned she would not receive enough requests from potential customers. However, she experienced that her customer base grew quite fast and highlighted that while it can be demanding when there are many requests, she also feels content and motivated by this.

Working environment challenges related to being self-employed

One of the cleaners I interviewed who worked for the platform company also stressed some of the risks of being self-employed, especially the fact that one cannot receive compensation for sick leave before the seventeenth day of being sick. She once had to cancel a week of jobs when she got sick and had no legal right to compensation, being self-employed. Moreover, she added that this is something you agree to by being self-employed and that the company is very transparent on this matter. It is my impression that both platform cleaners who were interviewed were well informed and aware of their rights and obligations towards the platform company. The cleaner also added that while most customers are flexible about changing the time of the appointment if a cleaner gets sick, it can be difficult to find new dates due to the rotation of jobs for other customers who book cleaning appointments regularly.

The other cleaner who worked for the platform company explained that as a self-employed worker, you have a say in how the working environment challenges you are exposed to affect you. For instance, the cleaner emphasized that the risk to your health, for example, depends on what chemicals you use or how heavy you choose to lift. When providing cleaning services through Vaskehjelp, the customer is responsible for providing the equipment and cleaning supplies necessary for the job they want carried out. Both cleaners I interviewed who worked for the platform described having taken precautions to mitigate the potential negative effects of using equipment and chemicals that can be harmful to one’s health. For instance, both had encouraged their customers to choose milder cleaning supplies and chemicals: “I try to promote natural products. Cleaning chemicals can intensify the risk of asthma. I try to inform the customers, and we help each other. It is good for me, their homes and their families” (cleaner, platform company), one argued. Another highlighted: “If the customers use some of the cheaper chemicals that are bad for you, you can ask them [to change]. Everything is up to us. Some cleaners don’t ask their customers, but the customers probably don’t think about these things if you don’t ask (…) If they like you and the job you do, they would like you to come back” (cleaner, platform company).

Nonetheless, to be able to influence these factors, cleaners must have the courage to discuss these matters with the customer, so one again must consider cleaners’ dependence on good relations with the customer to ensure good customer reviews. In these cases, language barriers can also pose a challenge. The consequence of using harmful cleaning supplies was also pointed out by the cleaner I interviewed who worked for a smaller company in the private market:

The company I work for now is one of the best companies I have worked for. The only thing is that we don’t get professional equipment, everything is bought from “Europris” [a discount retail store]. We need to use a lot of energy with such bad equipment. My back and wrists hurt. (cleaner, private market)

The above quote shows the importance of appropriate equipment to mitigate the risk of musculoskeletal injuries, considering that almost half of all cleaners report neck, shoulder and back pain, and that most of them say it could be due to their work (NOA, n.d.). Again, the choice of cleaning supplies and chemicals is not in the hands of the platform cleaners unless they demand better equipment from their customers.

Despite offering courses online, Vaskehjelp does not provide cleaners with compulsory OSH courses concerning the use of equipment and chemicals. Cleaners must therefore look up this kind of information on their own initiative. The regional safety representative I interviewed also emphasized this aspect. He stressed that the most prevailing working environment challenge for platform workers in the cleaning industry is that companies abdicate their responsibilities. He assessed that platforms do not provide training or information about protective equipment and chemicals. The regional safety representative put it like this: “The app companies are different from other cleaning companies in several negative ways – the cleaners lack insurance and information on asthma and allergies, they lack rights. They lose all rights one has as an employee” (regional safety representative).

Authorities’ challenges

It was pointed out by several of the interviewees that there is a substantial difference between the private and the professional cleaning markets. They emphasized that they found it very difficult to get an overview of the private market, which is where the platforms mainly operate. The regional safety representative I interviewed argued that it is difficult to say anything about the private market at all:

We know it is big, but it is difficult to get an overview. There are many sole proprietorships, no company cars with logos for us to see where the cleaners are, no websites with information, and a lot of undeclared work. (regional safety representative)

One of the cleaners I interviewed who works in the private market had a lot of experience from various smaller, traditional cleaning companies. To illustrate the unpredictability in parts of the private market, she told us about the wage and working conditions that characterized her everyday working life when she first moved to Norway from an Eastern European country:

She [the employer] would pay us in cash, and we were driving our own cars. She did not pay for gas. I had nowhere to go, I needed the work. I expected her to give me a contract or something. She said, “now you will be paid 110 kroner an hour because of the taxes”. But what taxes do you pay with undeclared work? (…) She was very smart. She had all these girls who did not speak English very well and were too scared to leave. (cleaner, private market)

The representatives I interviewed from the trade union shared this impression of the private market. They informed us that while the union density in the industry at large is quite low, most of their members are employed in larger companies in the professional market. One reason for this is that these cleaners are easier to reach than the cleaners in the private market. Another reason is that a larger share of the cleaners in the professional market are employed, in contrast to the private market where self-employment is more common, making cleaners in the private market more difficult to unionize.

Similarly, the representative from the tripartite sector programme described the private market as a “grey market” and acknowledged that the authorities and social partners who should have knowledge about the private market and the platforms who operate there do not. The sector programme has only recently started investigating the parts of the cleaning industry where platforms operate. The programme representative admitted finding it difficult to get an overview of this part of the market, partly because it is challenging to carry out inspections in private homes, making the cleaners who work for platforms very difficult to reach.

The scheme of regional safety representatives was implemented to secure OSH in the industry. Nonetheless, the regional safety representatives get their mandate from the WEA and therefore only visit companies with employees. For this reason, platform workers, who tend to be classified as self-employed contractors, are generally not covered by the scheme. The regional safety representative I interviewed told us that cleaners often are difficult to reach. The main reasons for this are language barriers and the fact that cleaners consequently do not know what regulations apply to them, or the rights to which they are entitled. The representative stressed that many cleaners often find it difficult to search for this type of information as many of them have only lived in Norway for a short period of time, often taking on cleaning jobs because they need the money. Very often, information on rights and duties are only available in Norwegian and English.

While platform workers generally are not part of these safety representatives’ mandate, regional safety representatives get an impression of platform companies and the cleaners who work for them through their work in the private cleaning market. For instance, they meet platform cleaners when approaching cleaners in shopping malls and the like. When they ask to see the cleaners’ HSE cards, some of them have a stack, as they work for several companies. In these cases, the safety representatives see that some of them carry HSE cards as self-employed cleaners – some of whom work through digital platforms.

3.6 Concluding discussion

The aim of this chapter has been to explore the risks and working environment challenges that characterize platform work in the Norwegian cleaning industry. In this concluding discussion, I review some of the most salient challenges that have been highlighted throughout the chapter. First, in line with Wiesböck et al. (2023), I find that a great deal of power is granted to the customers through the use of customer reviews. In the case of Vaskehjelp, customers choose whether they would like to give the cleaner a “thumbs up” for the job, which affects the cleaner’s online score and thus prospective job opportunities and income.

Second, I find time management to be another working environment challenge platform cleaners face. Cleaners who work for platforms make their own schedules depending on pending requests from customers, how many jobs they need, how long each job will take, and how long it takes to commute it between jobs. It is the cleaner’s responsibility to make sure that each job is carried out within the time frame decided by the customer. This again highlights cleaners’ dependence on customers. While a cleaner can suggest extending the time frame for additional pay, or focusing on parts of the job, they must keep the need for a good review in mind. Leanerts et al. (2022) emphasize how maintaining a good rating, or dealing with the consequences of a bad rating, causes a lot of stress for platform workers. As opposed to platform cleaning, traditional cleaning is not characterized by this specific stress element.

Third, platform cleaners are exposed to the same OSH risks as traditional cleaners, including work pressure, contact with water and chemicals, the use of airtight gloves, heavy lifting, working on their knees or with their hands above their shoulders and working alone. Nonetheless, it is the customer that is responsible for providing platform cleaners with equipment and chemicals, and the cleaners must then evaluate whether the equipment is adequate and safe for their health. The platform does not require cleaners to have the training necessary to make this evaluation as they are self-employed. If cleaners consider the equipment inadequate, they must dare to tell the customer themselves and ask if this can be changed, again keeping in mind the need for a good review.

Fourth, as self-employed workers, platform cleaners are excluded from the rights and benefits employed cleaners have through the WEA and the collective agreement. As the cleaning industry is largely made up of foreign-born workers, language barriers and lack of local knowledge mean that many cleaners might be unaware of the legal and economic consequences of self-employment. Becoming a cleaner who works for a platform company requires minimal prior knowledge about the occupation and the industry. One can easily find the information through the platform’s website about how to establish a sole proprietorship, create a profile and apply for an HSE card. What is described as the main advantage of being a platform worker – the flexibility – might therefore also becomes the greatest disadvantage if cleaners do not know what it involves or how to manage it.

In sum, cleaners in general are exposed to work pressure, contact with water and chemicals over time, heavy lifting, straining work positions and working alone (NOA, n.d.; Trygstad et al., 2018). This is also true for platform cleaners. In addition, like many traditional cleaners, platform cleaners are generally classified as self-employed workers and therefore excepted from a number of labour rights and welfare benefits traditional employees are entitled to (Jesnes, 2019). Moreover, as emphasized by Lenaerts et al. (2022), while traditional employees and platform workers might carry out similar tasks, and be exposed to the associated risks, the risks are likely higher for the platform worker. One important reason for this is the working environment risks that accompany digital work arrangements, such as customer reviews and the stress related to having to attain a good rating to secure jobs in the future. Ultimately, platform cleaners are exposed to a combination of the OSH risks that characterize the cleaning industry in general and risks associated with atypical forms of employment, in addition to OSH risks associated with digital work arrangements.

Bibliography

Alsos, K., & Eldring, L. (2014). Solidaransvar for lønn. Fafo report 2014:15. Fafo.

Altinn. (2017). What is Altinn? Accessed from https://info.altinn.no/en/about-altinn/what-is-altinn/, 30 May 2024.

Andersen, R. K., Bråten, M., Steen-Jensen, R., Trygstad, S. C., & Walbækken, M. M. (2021). Innkjøp av renholdstjenester i proffmarkedet. Fafo report 2021:19. Fafo.

Andersen, R. K., Bråten, M., Nergaard, K., & Trygstad, S. C. (2016). «Vi må ha is i magen og la tiltakene få virke». Evaluering av godkjenningsordningen i renhold. Fafo report 2016:18. Fafo.

Arbeidsmiljøloven. (2005). Lov om arbeidsmiljø, arbeidstid og stillingsvern mv. (LOV-2005-06-17-62). Lovdata. Accessed from https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2005-06-17-62, 30 May 2024.

Eurostat. (2023). Glossary: Statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community (NACE). Accessed from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Statistical_classification_of_economic_activities_in_the_European_Community_(NACE), 30 May 2024.

Hotvedt, M. J. (2020). Protection of platform workers in Norway. Part 2 Country report. Nordic future of work project 2017–2020: Working paper 09. Pillar VI. Fafo.

Jesnes, K., & Oppegaard, S. M. N. (2023). Plattformmediert gigarbeid i Norge. Fleksibilitet, uforutsigbarhet og ulikhet. In Fløtten, T., Kavli, H. C. & Trygstad, S. (Eds.) Ulikhetens drivere og dilemmaer, pp. 137–153. Universitetsforlaget. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18261/9788215065403-23-08.

Jesnes, K. (2019). Employment models of platform companies in Norway: A distinctive approach? Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 9(6), 53–73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18291/njwls.v9iS6.114691.

Jordfald, B., & Svarstad, E. (2020). Renholderes lønnsbetingelser før og etter allmenngjøring. Privat og offentlig sektor. Fafo report 2020:13.

Kusk, K., Duus, K, Hansen, S. S., & Floros, K. (2022). Det usynlige menneske i platformsarbejde – en kvalitativ undersøgelse af algoritmisk ledelse. Tidsskrift for arbejdsliv, 24(3). DOI: https://doi.org/10.7146/tfa.v24i3.134746.

Lenaerts, K., Waeyaert, W., Gillis, D., Smits, I., & Hauben, H. (2022). Digital platform work and occupational safety and health: overview of regulation, policies, practices and research. EU OSHA. DOI: 10.2802/236095.

NOA. (n. d.). Fakta om arbeidsmiljøet blant renholdere. Accessed from https://noa.stami.no/yrker-og-naeringer/noa/renhold/, 30 May 2024.

Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority. (n.d. a). Renholdsregisteret. Accessed from https://www.arbeidstilsynet.no/godkjenninger/renholdsregisteret/, 30 May 2024.

Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority. (n.d. b). Occupational health services (OHS). Accessed from https://www.arbeidstilsynet.no/en/hse-cards/roller-i-hms-arbeidet/occupational-health-services/, 30 May 2024.

Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority. (2023, 15 June). Minstelønn. https://www.arbeidstilsynet.no/arbeidsforhold/lonn/minstelonn/

Proff. (n.d.). Proff – The Business Finder. Accessed from https://www.proff.no/info/om-proff/, 30 May 2024.

Spilda, F. U., Howson, K., Johnston, H., Bertolini, A., Fuerstein, P., Bezuidenhout, L., Alyanak, O., & Graham, M. (2022). Is anonymity dead?: Doing critical research on digital labour platforms through platform interfaces. Work Organization, Labour & Globalisation, 16(1), 72–87. DOI: 10.13169/workorgalaboglob.16.1.0072.

Trygstad, S. C., Andersen, R. K., Jordfald, B., & Nergaard, K. (2018). Renholdsbransjen sett nedenfra. Fafo report 2018:26. Fafo.

Valestrand, E. T. (2023). Hvem holder Norge rent? Renholdsbransjen og arbeidsstyrkens særtrekk – segmentert og kjønnet arbeid. In Villa, M., Valestrand, E. T. & Rye, J. F. (Eds.) Migrasjon og mobilitet – handlinger, mønstre og forståelser i norsk sammenheng, pp. 125–147. Cappelen Damm Akademisk. DOI: https://doi.org/10.23865/noasp.181.ch6.

Valestrand, E. T., & Oppegaard, S. M. N. (2022). Framveksten av plattformmediert gigarbeid i Norge og den «norske arbeidslivsmodellen» En analyse av drosjenæringen og renholdsbransjen. Norsk sosiologisk tidsskrift, 6(5), 25–43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18261/nost.6.5.3.

Vaskehjelp. (n.d. a). Vaskehjelp. Accessed from https://vaskehjelp.no/, 10 October 2023

Vaskehjelp. (n.d. b). How to become a Vaskehjelp cleaner. Accessed from https://vaskehjelp.no/renholder/, 20 August 2023.

Wiesböck, L., Radlherr, J., & Vo, M. L. A. (2023). Domestic cleaners in the informal labour market: New working realities shaped by the gig economy? Social Inclusion, 11(4). DOI: https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v11i4.7119.