8. PREVENTIVE EFFORTS AND WHO LIVE LIFE INTERVENTIVE PILLARS

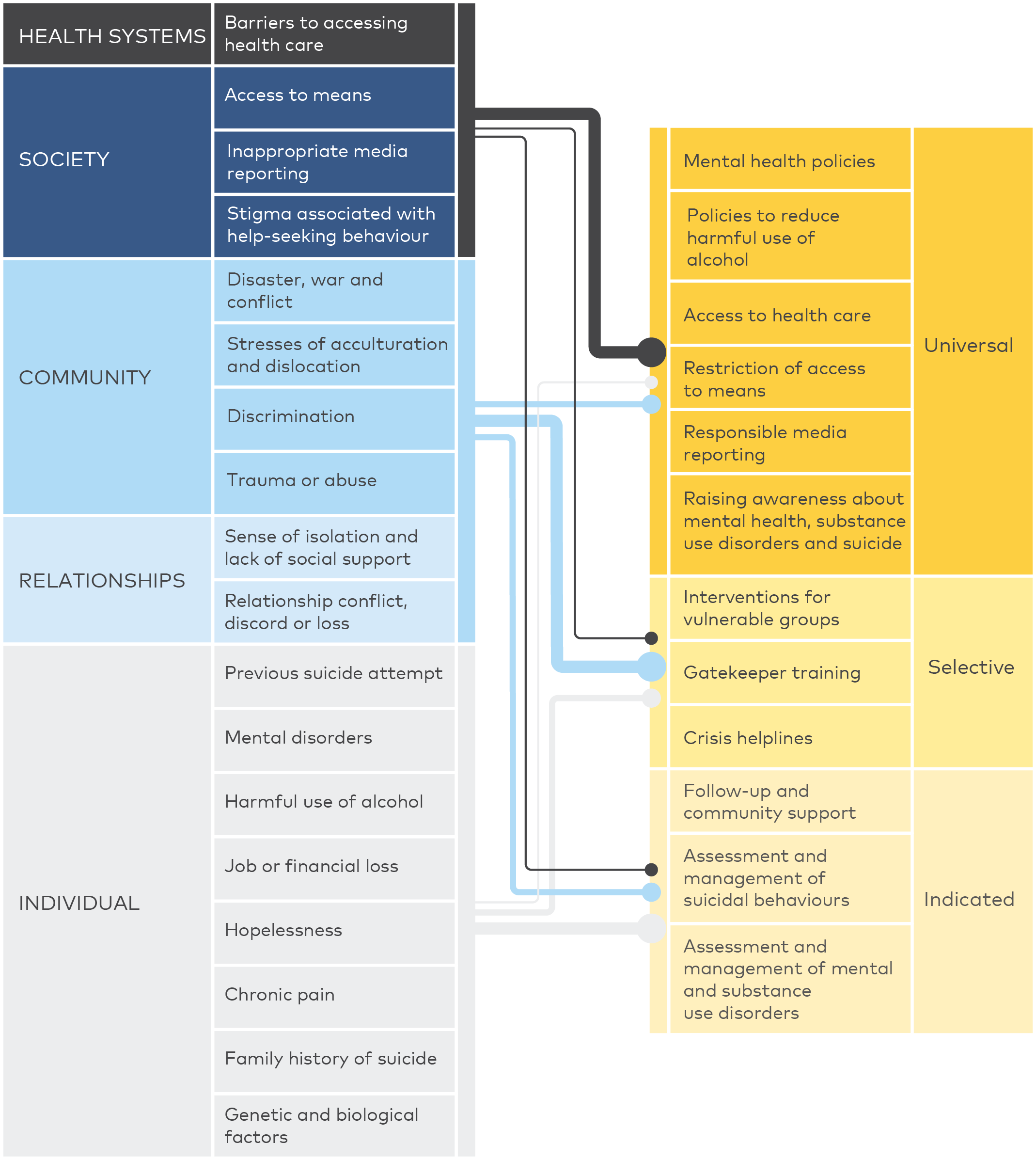

Given that suicide is an outcome of multiple factors, a national plan for suicide prevention should be multi-level and multi-modal. Consequently, the effect of a national plan for suicide prevention depends on its different components and whether these are implemented successfully. The theoretical basis for national preventive efforts follows the U-S-I model introduced by the US Institute of Medicine (Mrazek & Haggerty, 1994), which divides preventive strategies into universal, selective and indicated interventions. Universal prevention addresses the entire population, for instance through awareness raising to reduce stigma and restricting access to suicide methods (Figure 7.1). Selective prevention consists of efforts to reduce suicide risks among vulnerable groups who are known to have an excess suicide rate, for instance individuals with mental disorders or homeless people who might be supported through telephone helplines and gatekeepers. Indicated prevention focuses on individuals at risk of suicide and might include psychosocial therapy or medicine (World Health Organization, 2014).

The body of evidence regarding effective interventions has grown substantially over recent decades, and there are numerous evidence-supported interventions which may be directed towards several of the identified high-risk groups (Mann, et al., 2021a). Yet, there is still need of effective interventions for other high-risk groups. Three international systematic reviews and one umbrella review were consulted for current evidence regarding promising strategies for suicide prevention (Mann, et al., 2021b, Mann, et al., 2005a, Zalsman, et al., 2016). The following section will briefly lay out their main recommendations.

Based on existing evidence, specific types of interventions have been identified as effective (Table 7.1). Many of these intervention are included in WHO’s LIVE LIFE guide’ four key interventions: 1) means restriction; 2) collaboration with relevant media actors; 3) promotion of mental health among young people; and 4) early identification, assessment, treatment and follow-up of persons affected by suicide (including psychosocial therapy) (World Health Organization, 2021a). The existing evidence within these areas is reviewed in the next sections.

Figure 8.1 Risk factors and preventive efforts (WHO, 2014).

Evidence for the effectiveness of suicide preventive interventions is essential for guiding national investments. The quality and rigorousness with which interventions is evaluated, also referred to as level of evidence, is an important factor to consider when comparing supportive evidence of different interventions. Means restriction is one of the prevention strategies with most supportive evidence. However, evaluations of these efforts have mainly been based on study designs where pre- and post-measurement are compared without accounting for other potential influential factors. On the other hand, psychosocial therapy for people at risk of suicide has generally been tested in more rigorous study designs, such as randomised clinical trials, which have a high level of evidence. It is possible that more psychosocial therapy interventions would appear to be effective if they had been evaluated using the same study designs as those of means restrictions. It is, thus, important to take the study design into consideration when comparing the evidence, which supports different strategies.

Due to a scarcity of evidence from the Nordic countries, evidence from other countries is also included. Other evidence-supported interventions include training of primary care physicians, community-based interventions, and treatment with ketamine, which are briefly outlined below.

Efforts strengthening primary care physicians to detect and better treat depression in Sweden and screening for depression among older adults in rural settings in Japan have both been linked to reductions in the number of suicides (Oyama, et al., 2008, Rutz, et al., 1995). The German Depression Alliance is a community-based effort, which consists of campaigns, psychoeducation and better detection of depression, and has been linked to reductions in suicidal acts although later a follow-up study showed ambiguous findings regarding suicide deaths (Hegerl, et al., 2006, Köhler, et al., 2021). Gatekeeper training where stakeholders are trained to intervene if they identify members in their community who are at risk of suicide has successful been implemented in the US Air Force and Norwegian military (Mann, et al., 2005a, Knox, et al., 2003).

Recent studies showed that treatment with ketamine has the potential to eliminate suicide thoughts almost instantly. This is a relatively new area but promising findings are emerging from several studies (Abbar, et al., 2022). Also treatment with lithium for individuals with bipolar disorders and with clozapine for individuals with psychosis have good evidence (Mann, et al., 2005a).

Table 8.1 Overview of effective interventions and level of evidence.

Universal prevention | Intervention and effect | Level of evidence* |

|---|---|---|

Means restriction | Smaller pack sizes and withdrawal of medication, barriers on bridges, introduction of catalysators, stricter gun laws, and fences at railways (see Section 7.1). | †† |

School-based intervention | The Good Behavior Game has been linked to reduced risks of suicidal ideation (see Section 7.3). | †† |

School-based intervention | The Youth Aware of Mental Health Programme has been linked to reductions in self-harm episodes (see Section 7.3). | ††† |

Primary care physicians | Supporting primary care physicians to detect and treat depression was linked to an almost 60% reduction in female suicides. After end of the educational effort, effects subsided.(Rutz, et al., 1995) | †† |

Public education campaign | A community-based effort consisting of campaigns, psychoeducation and better detection of depression resulted in 20% reduction in the number of suicidal acts. A multi-sites assessment did not reveal pre versus post differences in the number of suicide deaths.(Hegerl, et al., 2006, Köhler, et al., 2021) | †† |

Selective prevention | ||

Gatekeeper training | Multi-component intervention where training of US Air Force leaders to detect and intervene was combined with treatment options was linked to a 33% reduction in numbers of suicide.(Knox, et al., 2003) In the Norwegian military, information session, helplines, gatekeeper training, medical and welfare support were implemented and well received.(Mehlum & Schwebs, 2001) | † |

Detecting and treating depression in primary care | Community-based screening for depression and later follow-up was linked to fewer suicides among older adult males and females.(Oyama, et al., 2008) | ††† |

Detecting and treating depression in primary care | Detection of depression in the waiting room of primary care physicians and assignment of case manager for older adults resulted in reduced levels of suicidal ideation.(Bruce, et al., 2004, Unutzer, et al., 2006) | ††† |

Lithium treatment | Lithium treatment for individuals with bipolar disorder was associated with lower risks of suicide.(Kessing, et al., 2005, Fitzgerald, et al., 2022) | †† |

Ketamine treatment | Ketamine treatment for individuals with suicidal ideation was associated with eliminating suicidal ideation within 3 days.(Abbar, et al., 2022) | ††† |

Indicated prevention | ||

Psychosocial therapy | Psychosocial therapy for individuals after suicide attempt in the Danish Suicide Prevention Clinics was linked to fewer repeat suicide attempts, suicides, and deaths.(Erlangsen, et al., 2014) | †† |

Psychosocial therapy | Outreach and psychosocial therapy for individuals after suicide attempt in the Danish Suicide Prevention Clinics was linked to 8.7% fewer repeat suicide, suicides, and deaths.(Hvid, et al., 2011) | ††† |

Dialectic behavioural therapy (DBT) | Individuals with borderline personality disorders and self-harm behaviour offered DBT were found to have fewer self-harm events.(Mehlum, et al., 2019) | ††† |

Brief intervention | Individuals presenting to emergency department with suicide ideation or attempt were provided with risk assessment, discharge resources, and telephone calls, which was linked to a 5% reduction in repeat suicide attempts.(Miller, et al., 2017) | †† |

Safety planning | Provision of a safety plan to patients at risk of suicide was linked to a 43% reduction in suicidal behaviour.(Nuij, et al., 2021) | ††† |

Brief intervention after suicide attempt | Individuals seen in Emergency departments were provided with a 1hrs. psychoeducation and nine subsequent contacts by phone or in-person. The intervention was evaluated in five countries where no existing psychiatric services were offered for this target group.(Fleischmann, et al., 2008) | ††† |

Online therapy | Individuals with suicide thoughts were offered access to 6-module online-therapy program, which was found to reduce level of suicide thoughts.(Mühlmann, et al., 2021) | ††† |

* Level of evidence was rated according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine.(Centre for Evidence-based Medicine, 2001) Level of evidence was rated according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (OCEBM).(Centre for Evidence-based Medicine, 2001) † Quasi experimental or ecological study designs (rated as 2B or 2C in OCEBM). †† Cohort studies (rated as 2A in OCEBM). ††† Meta-analysis or randomized clinical trials (rated as 1B in OCEBM).

8.1. MEANS RESTRICTION

Means restrictions has been recommended as one of the most promising strategies for prevention of suicide (Mann, et al., 2005b). Examples of restricting access to suicide methods, include reducing pack sizes of pain killers and putting up fences or barriers at public sites of suicide (‘hotspots’). The approach is based on the insight that people who carry out suicidal acts are often in a psychological crisis, acting impulsively on an unbearable, psychic pain while also likely to experience ambivalent feelings regarding the outcome of the event. By making suicide methods less accessible, one wins time. If the method of choice is not available, the person might instead seek help, the suicidal crisis might subside before another method is found, or the person might be identified by friends or bystanders and aided to support. The majority of individuals who survive a suicide attempt do not carry out a new attempt (Carroll, et al., 2014); thus supporting the notion that they were ambiguous about their suicide thoughts.

On a national level, making a specific suicide method unavailable may translate into hundreds of saved lives. Concerns that people might resort to other methods have been voiced but has not been supported by conclusive evidence. Also, if access to a highly lethal method is restricted then a substitution is still expected to result in lives saved (Gunnell, et al., 2017). This section will review the experiences with means restriction within the Nordic countries.

Poisoning is one of the most frequently used suicide methods, for instance paracetamol poisoning. A legislative change, which reduced pack sizes of non-opioid analgesics in pharmacies and non-pharmacy outlets, was linked to 43% fewer deaths and 61% fewer liver transplants in England and Wales (Hawton, et al., 2013). Inspired by these findings, the Danish Ministry of Health introduced a pack size restriction on weak analgesics in pharmacies in 2013. This restriction was followed by a reduction of 18% in hospital-presentations for non-opioid analgesic poisoning, which was further supported by reductions of alanine transaminase levels in blood tests, suggestive of fewer of liver failures (Table 7.2) (Morthorst, et al., 2020b). An earlier legislative measure had introduced an 18-year age limit on purchases of non-opioid analgesics in Denmark in 2011. This was associated with a 17% reduction in admissions for non-opioid analgesic poisonings among adolescents aged 10-17 years (Morthorst, et al., 2020b).

Earlier data bring evidence of other successful restrictions. In the late 1980s, barbiturates and dextropropoxyphene could no longer be prescribed. This was followed by a reduction in the number of suicides (Nordentoft, et al., 2007). On a similar note, the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), as a less toxic alternative to the tricyclic antidepressants, has been linked to a reduction in the number of suicides, although the onset of the two events, i.e. introduction of SSRIs and decline in the suicide rate, did not coincide (Isacsson, et al., 2009).

In Sweden, a restriction in the number of caffeine pills, which could be bought over-the-counter, was followed by an elimination of suicides due to overdose with caffeine pills in the subsequent two years (Thelander, et al., 2010). Although relatively few suicides occur by overdose of caffeine pills in the Nordic countries (Thelander, et al., 2010, Holmgren, et al., 2004), a detailed assessment of all medication used in suicide overdoses might identify other agents, which ought to be addressed through restrictive interventions.

In most of the Nordic countries, electronic databases and patient journals facilitates monitoring of the medication prescribed to a patient, thus, reducing risks of over-prescriptions. On-going revisions regarding availability and pack sizes of medication is currently being conducted in Iceland. In Denmark, a new project will collect detailed information from electronic patient journals regarding drugs used for suicide attempts with the purpose of reviewing and, potentially, identifying medication, which should be addressed by pack size restrictions.

Hanging remains the most frequently used method of suicide in the Nordic countries. While it challenging to prevent access to this method, individuals belonging to high-risk group who may be living in confined settings, such as psychiatric hospitals, nursing homes, and correctional institutions, where, for instance, ligature points may be removed and personal items may be contained (Gunnell, et al., 2005).

An international meta-analysis on installation of barriers on bridges or viaducts found a 28% reduction in the number of suicide death during subsequent years when compared to the years before the intervention. A slight increase in incidents at nearby bridges was factored into the analyses (Thelander, et al., 2010, Pirkis, et al., 2013). When compared to other suicide preventive strategies at public sites, means restriction seems to be most effective. A series of meta-analyses linked means restriction to a 91% reduction of suicides, while encouragement of help-seeking was linked to a 51% reduction and intervention by third party to a 47% reduction (Pirkis, et al., 2015). Several bridges in Sweden were identified, as public sites of suicide, resulting in recommendations of setting up barriers (Lindqvist, et al., 2004). A Norwegian study showed that six bridges accounted for 46% of all ‘bridge suicides’. Barriers were installed on three of these, while one bridge was only partly covered by barriers. No suicides occurred on the two bridges, which were fully covered by barriers, whereas some incidents were observed at the bridge partly covered by barriers (Sæheim, et al., 2017).

Car exhaust, containing carbon monoxide, was a relatively frequent suicide method during the 1970s and 1980’s. However, the introduction of catalytic converters in car exhaust systems implied that this method was gradually phased out during the 1990s (Nordentoft, et al., 2007).

A substantial share of suicides in Finland, Greenland, Iceland, and Norway took place by shooting. Findings suggest that availability of firearms might be linked to suicide, for instance, among young males in Northern Finland (Lahti, et al., 2014). Stricter gun laws, in the form of making acquisition less easy and introducing mandatory safe storage, have been linked to a decrease in suicides by firearms among males in Norway during the 1990s (Puzo, et al., 2016). In Denmark, a decline in the number of suicides due to firearms has also been linked to stricter gun laws (Nordentoft & Erlangsen, 2019). Other countries, for instance, Iceland and Sweden have over the past decades introduced a stricter legislation regarding possession and storage of weapons. Also, in northern Sweden, a collaboration with the national hunting association has been initiated to promote awareness.

Although only around 5% of all suicides occur by railway, the personal and financial costs associated with this suicide method are considerable (Silla, 2022). Installation of barriers, for instance fences or wooden walls along the tracks, have been associated with fewer suicides at commuter stations in greater Stockholm, Sweden, while fewer suicides than expected were recorded at stations frequented by high-speed trains (Ceccato & Uittenbogaard, 2016). In an effort to counter this, fences were set up between railway tracks to prevent access to high-speed tracks. Substantial reductions were observed when compared to control stations in Stockholm, Sweden (Fredin-Knutzén, et al., 2022). However, an increase was seen at control stations, which were closely situated to the intervention stations. In Denmark, a pilot project of setting up signs, which encourage help-seeking, at railway stations has been evaluated positively in terms of reaching the target group. This was noticed by the national helpline for suicide prevention as they recorded calls from individuals who were evaluated to be at risk of suicide and had noticed the signs at the station (Erlangsen, et al., 2021).

Preventing access to suicide methods has been demonstrated to reduce the number of suicide deaths. Successful approaches include pack size restrictions on tablets, barriers on bridges, and stricter gun laws. For this reason, it is important to identify the specific drugs that are used for suicides as well as geographic locations of public sites.

Table 8.2 Restriction of access to means of suicide.

Method | Intervention | Outcome | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

Analgesics | 1) Introducing of smaller pack sizes. (Morthorst, et al., 2020b) 2) Restricting sales for adolescents below the age of 18. | 1) A reduction of 18% in non-opioid analgesic poisonings. 2) 17% fewer admissions for non-opioid analgesic poisoning among 10–17-year-olds. | †† |

Barbiturates | Restricting use of drug. (Nordentoft, et al., 2007) | Gradual phasing out of suicides by barbiturates. | † |

Bridges | Installation of barriers on bridges. (Sæheim, et al., 2017) | >78% reduction in suicide from bridges. | †† |

Bridges | Installation of barriers on bridges. (Fredin-Knutzén, et al., 2023) | An 83% reduction in suicides across four bridges. | † |

Caffeine tablets | Restricting number of pills in over-the-counter sales. (Thelander, et al., 2010) | Elimination of suicides by overdose of caffeine pills. | † |

Car exhaust | Introducing of catalysators on cars. (Nordentoft, et al., 2007) | Gradual phasing out of suicides by car exhaust. | † |

Firearms | Introduction of stricter gun laws. (Puzo, et al., 2016) | 4.3% reduction in suicides by firearms. | †† |

Railway | Installing mid-track fences to prevent access to high-speed tracks. (Fredin-Knutzén, et al., 2022) | 62.5% reduction in suicide rate at the station of the mid-track fence. | †† |

Level of evidence was rated according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (OCEBM).209 † Quasi experimental or ecological study designs (rated as 2B or 2C in OCEBM). †† Cohort studies (rated as 2A in OCEBM).

8.2. MEDIA REPORTING

Media outlets can play an active role in promoting help-seeking behaviour and prevention of suicide. Meta-analyses have shown that media narratives, i.e. stories presented in the media, which convey a sense of hope and recovery, have the potential to reduce suicidal ideation among vulnerable individuals (Niederkrotenthaler, et al., 2022). An example of this is the song by hip hop singer Logic. The song carried the title of the national telephone helpline for suicide prevention in the US, “1-800-273-8255” and it conveyed the importance of seeking help when experiencing suicide thoughts. During the months after the song’s release, an increased number of calls were recorded at the national helpline and the song was linked to a reduction of 245 suicides in the US (Niederkrotenthaler, et al., 2021a). Similarly, a documentary, which encouraged males to seek help when experiencing thoughts of suicide, was associated with increased help-seeking intentions in a randomised trial conducted in Australia (King, et al., 2018).

As proposed by the social learning theory, individuals may to adopt new behaviour by observing others (Bandura & Walters, 1977). This phenomenon has been coined as the Papageno effect. The name refers to a character in Mozart’ opera, the Magic Flute. In the opera, Papageno experiences a suicidal crisis but is then reminded by three elves of his reasons for living (Niederkrotenthaler, et al., 2010). The scene symbolises that suicidal crises may be temporary and subside and, also, that others can successfully reach out to people at risk of suicide. Given that many people who experience suicide thoughts do not actively seek help, media outlets could fulfil an important role by educating the public about self-care for mental health and the need for seeking help when in crises. By presenting positive role-models, for instance, stories of coping with life stressors or suicidal thoughts and how to get help, media may inspire individuals in similar situations to seek help.

There is consistent evidence that when sensational reports in the media, for instance on celebrities’ suicide, have been followed by copycat behaviours. The presentation of role models with suicidal behaviours, is suggested to lower the threshold for others to follow the same path. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated that both fictive and non-fictive reports of suicide can lead to copycat behaviors (Niederkrotenthaler, et al., 2021b, Niederkrotenthaler, et al., 2020).

Newspaper reports of celebrities who die by suicide have been followed by increases in the number of suicide deaths, in particular by the same method (Niederkrotenthaler, et al., 2020). For this reason, glorification and over-exposure of famous persons’ suicide should be avoided, including in fictional stories, such as televised or streamed series. This effect has been referred to as the Werther effect, named after the main character in the novel “The sorrows of young Werther” by Goethe, who dies by suicide in an unrequited love story. The book became popular in the late 18th century and was linked to copycat cases in contemporary Germany. Media reports on suicidal behaviour should not provide detailed description of suicide methods or explicit images. Furthermore, it is strongly recommended to list information on where people with suicide thoughts can get help, for instance listed in an accompanying box. WHO has developed a set of guidelines for media professionals (see box 7.2.1) and filmmakers (World Health Organization, 2023, World Health Organization, 2019)

It is important to practice caution when reporting on topics related to suicidal behaviour in the media. Famous persons may serve as role models and glorification of a celebrity’s suicide may seem encouraging to people in crises.

Celebrities generate a lot of interest, and the suicide death of Avicii, a famous Swedish DJ, was followed by intense activities in social media; network analyses revealed a strong response on social media, i.e. X (former Twitter). Findings revealed that tweets containing information related to the method of suicide were distributed to a larger group of followers than tweets, which did not mention the method (Niederkrotenthaler, et al., 2019). Dissemination on suicide method in social media is worrisome because it is challenging to control who might be affected. In Denmark, a closed forum on social media was found to be instrumental in several suicides and self-harm events among young females (Sørensen, 2020). In general, adherence to the WHO media guidelines is not enforced on social media.

Box 8.2.1. WHO Media guidelines

- Do provide accurate information about where to seek help for suicidal thoughts and suicidal crises.

- Do educate the public about the facts of suicide and suicide prevention based on accurate information.

- Do report stories of how to cope with life stressors and/or suicidal thoughts and the importance of help-seeking.

- Do apply particular caution when reporting celebrity suicides.

- Do apply caution when interviewing bereaved family or friends or persons with lived experience.

- Do recognize that media professionals may themselves be affected by covering stories about suicide.

- Don’t position suicide-related content as the top story and don’t unduly repeat such stories.

- Don’t describe the method used.

- Don’t name or provide details about the site/location

- Don’t use language/content which sensationalizes, romanticizes or normalizes suicide, or that presents it as a viable solution to problems.

- Don’t oversimplify the reason for a suicide or reduce it to a single factor.

- Don’t use sensational language in headlines.

- Don’t use photographs, video footage, audio recordings, digital or social media links.

- Don’t report the details of a suicide note.

Source: World Health Organization (2023).

Collaborations with media professionals are recommended. Stakeholders from the Nordic countries report of good collaborations with media professionals and that print media in general remember to provide information on where to find help when writing about suicidal behaviour. Several countries have translated the WHO media guidelines – or provide a brief summary of its main points - in the national language. In Norway and Sweden, organisations have succeeded with updating the national press ethical guidelines to ensure that they reflect the WHO recommendations. There is also systematic and on-going monitoring of reports on suicidal behaviour in the general media to assess whether they adhere to existing guidelines. Based on such effort, Swedish researchers have noticed an improvement in media reporting practices over time.

Awards for media professionals who adhere to the WHO media guidelines have been positively evaluated (Dare, et al., 2011). This practice already exists in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, from 2024 it will be introduced in Iceland.

Table 8.3 Experiences with media and suicide prevention.

Denmark | Faroe Islands | Finland | Greenland | Iceland | Norway | Sweden | Aaland Islands | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Media | ||||||||

Does the print media in general adhere to WHO's media guidelines? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

How is the general collaboration with media professionals regarding communication on suicidal behaviour? | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

Are there any controlling efforts to regulate communication on suicidal behaviour in social media? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

Do you have an award for good media reporting on suicidal behaviour? | Yes | No | No | No | Yes (from 2024) | Yes | Yes | No |

Based on statements from researchers in the field of suicide prevention.

8.3. PROMOTION OF MENTAL WELLBEING IN YOUTH

Concerns regarding young people’s mental well-being have emerged from recent reports in several of the Nordic countries (Stoltenberg, 2022).

With the aim of promoting mental health in youth, several promising school-based interventions have been developed, some of which are described in this section. The majority of these efforts address mental well-being in general among children and adolescents.

One such school-based intervention is the Good Behaviour Game. It consists of a team-based competition, which allows teachers to set standards for good behaviour and promote socialisation of children with maladaptive behaviours (Wilcox, et al., 2008). The program is aimed at children aged 5-7 years who are assigned to equally distributed teams in terms of sex, social isolation, and disruptive behaviour. Based on classroom rules, teams can win points during assigned periods. The implicit goal is that children discover it is in their own interest to present good behaviour and the maladaptive children’s behaviour is regulated by classmates. The intervention has been linked to reduced risks of suicidal ideation, and other adverse mental health outcomes, such as substance misuse (Wilcox, et al., 2008). The Good Behaviour Game is currently being tested in a Swedish cluster-randomized trial where teacher’s ratings conduct problems in class will form some of the outcomes (Djamnezhad, et al., 2023).

In 2020, WHO and United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) released the toolkit, Helping Adolescents Thrive (HAT), which aims at promoting adolescent mental well-being and preventing self-harm (World Health Organization, 2020b). The kit is directed towards adolescents aged 10-14 years, their caregivers, schools, community, and governmental agencies. The toolkit is based on evidence-informed strategies, which actively promotes access to mental health care for young persons, resources for schools and communities, outline of interventions for caregivers, and examples of psychosocial interventions for youth (World Health Organization, 2020b). This tool is seemingly not being used in the Nordic countries.

The school-based intervention, Youth Aware of Mental Health Programme (YAM), is a manualised program using role-playing and a booklet to increase awareness about mental health and introduce skills for coping with life stressors. One of its strategies involves encouraging young adolescents to look out for each other. The program, which is aimed at 15-year olds has been linked to reductions in self-harm episodes in a randomised clinical trial (Wasserman, et al., 2015). Interestingly, peer support was identified as the effective component rather than teacher intervention. The YAM intervention has been tested in Norway with the recommendation of its implementation (Pedersen, 2022). YAM is currently being introduced in the Swedish school system and will soon be tested for its feasibility in Denmark.

Supported by a recent act passed by the Icelandic Parliament, work is being done to introduce mental health as a separate subject in primary schools. Also, dialectical behavior therapy, as a skills training for emotional problem-solving (DBT STEPS-A) (Flynn, et al., 2018, Gasol, et al., 2022), is currently being tested as a pilot project in Iceland.

8.4. EARLY INTERVENTION

Support for persons at risk of suicide is a crucial element in suicide prevention. Some people who experience suicidal ideation actively seek help, either in general or mental healthcare settings or with community-based organizations. Others might choose to disclose it to people close to them or call a telephone helpline. International reviews revealed that people after self-harm have elevated risks of repeating the behaviour also with fatal consequences, particularly within the first year after the episode (Carroll, et al., 2014, Bergen, et al., 2012). This emphasises the importance of providing support for people who have had a suicide attempt.

This section will review some of the different options for reaching providing support for those who have had a suicide attempt, for instance through brief interventions and psychosocial therapy. On a wider scale, options for reaching out to those at risk of suicide, for instance through follow-up after discharge from psychiatric hospital, telephone helplines, and eHealth tool, are also addressed. Evidence related to interventions provided in a Nordic setting are prioritised.

8.4.1. BRIEF INTERVENTION

Brief interventions, such as a safety plan, which was developed to be administered during ED-presentations for suicide attempt, have been recommended (Stanley & Brown, 2012). Safety plans are often used in connection with psychiatric treatment, for instance in out-patient settings. However, it may also be considered in ED-department of general hospitals, given that international meta-analyses document that safety plans are linked to reductions in suicidal behviour (Nuij, et al., 2021). Findings suggest that less than half of those who presented with suicide attempt at Danish emergency departments went on to receive psychiatric treatment (Dyvesether, et al., 2022). Clinical guidelines specify the need for a psychiatric assessment of patients who attend the ED-department and conducted by a psychiatrist or staff from the psychiatric clinic. This may, however, not always take place, especially during evenings and weekends (Kapur, et al., 2008).

The clinical focus on risk screening tools has been criticized by mental healthcare professionals; some perceived that administrative tasks prevent them from using the limited time in a busy clinical setting to relate to the patient (Espeland, et al., 2021). Psychiatric inpatients in Norway mentioned individualized treatment and the feeling of a companionship between the patient and the clinician as factors, which contribute to recovery (Hagen, et al., 2018).

A quality of care model consisting of monitoring and procedures for patients with suicide attempt has been implemented in Norwegian ED-departments and was evaluated positively by key informants (Mehlum, et al., 2010). This was further expanded to include municipalities where designated staff would coordinate aftercare, in collaboration with local hospitals, when being informed about individuals who were discharged from hospital after a suicide attempt (Mork, et al., 2010).

On a general level, municipalities with extended outpatient services have in Finland been linked to reductions in the suicide rate (Pirkola, et al., 2009).

8.4.2. PSYCHOSOCIAL THERAPY

Psychosocial therapies have been used to provide crises intervention and introduce problem-solving strategies to people after self-harm. This type of intervention has been evaluated as promising for youth and adults by Cochrane reviews (Witt, et al., 2021a, Witt, et al., 2021b).

A psychosocial support model, where young patients after a hospital presentation for suicide attempt received therapeutic support from a psychiatric nurse and a social worker, was developed in 1984 in Bærum, Norway (Dieserud, et al., 2000, Dieserud, et al., 2010). Comparing those who received the standard model with those who received an additional community-based support component, no significant differences were found with respect to repeat suicide attempt (Johannessen, et al., 2011). Engaging social workers to support individuals at risk of suicide was also a part of the treatment model for the Danish Suicide Prevention Clinics. The target group for these clinics is individuals who do not attend an existing out-patient team. Patients are offered 4-10 sessions of psychosocial therapy. When compared to individuals who did not attend the same care after a suicide attempt, the treatment in the Danish Suicide Prevention Clinics was linked to reductions in repeat suicide attempt, suicide and death by other causes (Erlangsen, et al., 2014, Birkbak, et al., 2016). In some regions, an extended version of the chain of care, which includes municipal social worker as a part is provided for children and adolescents (Morthorst, et al., 2021b).

Assertive out-reach, which was aimed to provide problem-solving and motivational support for individuals after a suicide attempt through case management, was tested in a randomized trial in Denmark. When compared to those allocated to standard care, no statistically significant difference was found for those allocated to the intervention group with respect to repeat suicide attempt (Morthorst, et al., 2012).

Psychosocial therapy models have been developed to target individuals with specific mental disorders, such as dialectic behavioural therapy for individuals with borderline personality disorders. In a Norwegian trial, adolescents with symptoms of borderline personality disorder and repetitive self-harm behaviour were randomized to dialectic behavioural therapy or standard treatment. After 19 weeks of follow-up, fewer self-reported self-harm events and suicidal ideation were reported among those allocated to the DBT-treatment (Mehlum, et al., 2014). Significantly fewer self-harm events were also confirmed after 3 years of follow-up (Mehlum, et al., 2019). In a Danish trial, no significant difference with respect to self-reported self-harm was found for individuals with borderline personality disorder randomized to DBT versus collaborative assessment and management of suicidality (CAMS) (Andreasson, et al., 2016).

Although described as a short intervention, the Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program (ASSIP) consists of approximately 3 sessions of psychotherapeutic and letters every 3 months over the subsequent one year (Arvilommi, et al., 2022). In Finland, ASSIP was compared to more general crisis counseling in a randomized clinical trial. No difference in terms of later suicide attempts was found between the two types of support when examined for a group of individuals after suicide attempt (Arvilommi, et al., 2022). Detailed analyses revealed that younger age and history of previous suicide attempt, mental disorders, borderline personality disorders were associated with repetition of suicide attempts. The ASSIP-program is available in relatively few cities in Finland, while DBT is available for people with borderline personality disorders in major cities.

8.4.3. FOLLOW-UP AFTER DISCHARGE

The high suicide rate has motivated interventions to support patients at the time of discharge from psychiatric admission as well as to facilitate the transition to out-patient treatment. The Danish SAFE-trial offered face-to-face meetings between inpatients and out-patient clinician before discharge and, later, at home plus involvement of next of kin. However, no observable difference was found with respect to suicide attempt and death by suicide at 6 months follow-up (Madsen, et al., 2023).

Interestingly, findings from Finland suggest that a structural change, leading to shorter hospital stays but more individuals receiving treatment, was not linked to an increase in the suicide rate among recently discharged patients (Pirkola, et al., 2007). On a whole, documentation on effective interventions for individuals recently discharged from psychiatric hospital is lacking and more research is needed.

8.4.4. TELEPHONE HELPLINES

Telephone helplines for suicide prevention exist in most Nordic countries. Findings from the Danish helpline show that as many as 20% of callers have had a previous suicide attempt and that 47% of callers had suicide thoughts at the time of calling (Jacobsen, et al., 2022). Thus, suggesting that helplines do reach their target group of individuals with suicide thoughts.

There is some support that callers have evaluated the provided support as beneficial. The evidence is, however, largely based on interviews with users or counsellors, i.e. an actual reduction in suicidal acts has not been demonstrated (Mishara, et al., 2007, Mishara, et al., 2022). In qualitative interviews, callers to a Norwegian diaconal helpline for suicide prevention mentioned the immediate empathy and emotion support, a perceived connectedness, as well as existential support (Vattø, et al., 2020). Helplines are often operated by volunteers and counsellors may find it emotionally stressful to respond to call and pre- and post-shift debriefing has been recommended (Vattøe, et al., 2020).

8.4.5. E-HEALTH TOOLS FOR SUICIDE PREVENTION

Over recent years, an increasing number of eHealth tools, i.e. online-based tools for improving health outcomes, have been developed, including apps with safety plans and online therapy for people at risk of suicide.

Internet-based therapy using cognitive behavioural therapeutic strategies and offered to individuals with suicide thoughts, has been shown to reduce levels of suicide thoughts in randomised clinical trials in both the Netherlands and Denmark (Mühlmann, et al., 2021, van Spijker, et al., 2014). These types of interventions have the potential for reaching individuals who may be at risk of suicide but are reluctant to seek help in the psychiatric health care system.

App-based versions of the safety plan are available in Denmark, Norway and Sweden (Larsen, et al., 2015, Suicide Zero, 2023). The elements of the app have been developed and validated in collaboration with users, next of kin, and clinicians (Buus, et al., 2018, Buus, et al., 2019).