5. Examples of quantifying economic impact and a system change

A common feature of the Nordic countries is that policy initiatives are always based on solid research and data-based knowledge. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in estimating and evaluating the economic and social significance of investments in early age. This chapter describes several examples from different Nordic countries, including a new Icelandic law on the integration of services in the interest of children´s prosperity, a model developed in Denmark to calculate educational investments, and a large-scale randomised controlled trial (RCT) in Finland on expanding free ECEC by two years of pre-primary education provision.

5.1 The prosperity act, Iceland

In Iceland, The Act on the Integration of Services in the Interest of Children’s Prosperity (the Prosperity Act) was unanimously approved by Parliament on 11 June 2021 and entered into force on 1 January 2022.

The Prosperity Act emphasises early assistance and access to coherent services for the individual. Under the Act, children and families deemed to be in need of early assistance and support of any kind are ensured access to a specific coordinator in the child’s own local environment. This coordinator provides information and instruction on services to ensure correct and timely access to assessments and coordinates benefits if there is a need for more targeted or specialised assistance than is available at the primary level.

If children and their families need more targeted or specialised assistance, i.e., on secondary or tertiary levels, they will be assigned a case manager by their municipality’s social services. The case manager will advise and give information on services, assist with access to assessments and/or analysis of a child’s needs, be responsible for drawing up a support plan, lead the support team and follow up on the services provided in accordance with the support plan.

During the preparation of the Prosperity Act, the Minister of Education and Children retained a third-party economist to analyse its cost-effectiveness and economic impact for both state and municipalities.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are potentially traumatic events that occur during childhood. They can negatively impact future wellbeing and be costly for the individual and society. It is estimated that additional government spending due to ACEs in 2018 was approximately ISK 100 bn (EUR 680 m). To put this in perspective, Iceland’s GDP for 2018 was ISK 2.803 bn.

The analysis projected that the Prosperity Act would reduce ACEs by 7% and make children 7% better at processing them. The cost-effectiveness of the changes would take several years to determine, i.e. the children affected reach adulthood.

Integration of services in the cause of children's wellbeing is a profitable long-term investment

Estimated costs, economies, and overall impact on public finance (ISK bn)*

- Costs remain similar while economies increase cumlatively year by year

- The annual gain will exceed costs in 2035

- Cumulative impact on public finance will be positive from 2050

- Funding spent on implementing the Bill will yield at 9,2% real rate of return**

Figure 1. A graph representing the estimated financial and economic impact of the integration of services in the interest of children’s wellbeing under the Prosperity Act in Iceland. An assessment was conducted by the Ministry of Social Affairs of Iceland in 2021.

* Figures are fixed price

** Internal rate of return of overall impact premised on 2% annual growth after 2070.

* Figures are fixed price

** Internal rate of return of overall impact premised on 2% annual growth after 2070.

According to the analysis, the annual gain will exceed costs in 2035, and the cumulative impact on public finances will be positive from 2050. The legislation is estimated to be cost-effective and will yield returns on par with the most profitable investments the Icelandic government has previously undertaken. In addition, the Prosperity Act will have no negative environmental impact, with only a positive impact on the lives of children and their families, leading to increased overall wellbeing and national prosperity.

5.2 REFUD model in Denmark

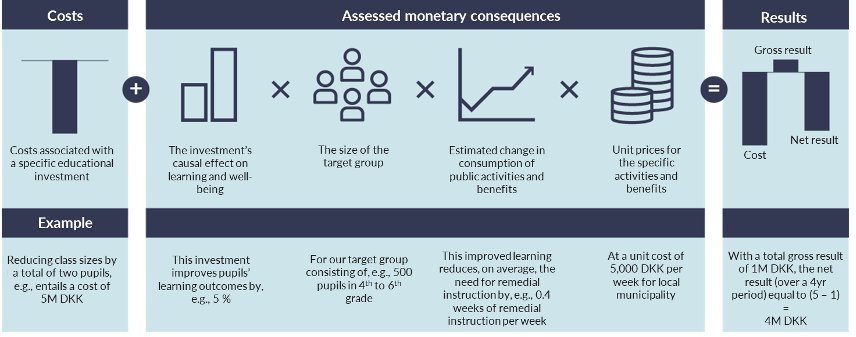

REFUD (Regnemodel for Uddannelsesinvesteringer) provides insight into the short-term economic consequences of educational investments in basic education and ECEC at the national, regional and municipality level. REFUD has two separate components: a Knowledge Bank and a Calculation Module.

The Knowledge Bank consists of a collection of quantitative research on children´s learning and wellbeing. In the field of ECEC, REFUD has focused on investments designed to lower child-to-staff ratios

The Calculation Module is based on the Washington State Institute for Public Policy's (WSIPP)cost-benefit model. It includes only short-term returns over a four-year period and solely evaluates monetary returns.

Figure 2. A simplified example of the calculation model in REFUD estimating the impact of a financial investment and the estimated monetary consequences of it in the field of primary education.

5.3 Finland’s pre-primary education expansion experiment

Professor Matti Sarvimäki from Aalto University presented the Finnish pre-primary education expansion experiment at the Nordic expert seminar in Reykjavik on 3 October 2023. The presentation included a particular focus on the political process involved and the commitment of the three most recent Finnish governments.

At present, Finnish children attend pre-primary education from the age of six and elementary school from the age of seven. The new intervention reduced the age at which mandatory pre-primary education starts by a year, from six to five.

In 2015, the newly elected government started a number of experiments in different policy fields to incentivise social innovation and development. First was the introduction of basic income on a trial basis. The following government continued this approach and introduced a randomised controlled trial (RCT) with two years of free pre-primary education.

In order to conduct the RCT, a specific Act was passed for the trial, the Act on a Two-Year Pre-Primary Education Trial (1046/2020). The randomisation was conducted in two steps: The selection from larger municipalities (those with a sufficient number of suitable ECEC units) was random, as was the division of ECEC units into treatment and control groups within this selected group of municipalities. For smaller municipalities (with only a few suitable ECEC units), the researchers randomised the entire municipality to either treatment or control.

Working with the Ministry of Education and Culture, researchers designed a randomised experiment to evaluate the impact of extending pre-primary education on children’s socio-emotional, numeric and language skills.

The treatment group (N ≈ 15,000) attended pre-primary education for two years instead of one, following a curriculum drawn up specially by the Finnish National Agency for Education for the two-year pre-primary education experiment. The control group (N ≈ 20,000) either continued with the business-as-usual early childhood education at daycare centres or stayed at home. The research team behind the trial evaluated each child three times between the ages of five and seven, using standardised tests and teacher evaluations. The primary outcomes are indices of socio-emotional, numeric and language skills. This data has been augmented using register-based data on the children and their parents.

The broader research project also includes online surveys for teachers, parents and civil servants, in-depth interviews with children and parents, and text analyses of administrative records.