- Full page image w/ text

- Authors

- Table of contents

- Executive summary

- List of Acronyms

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Background

- 2.1. Biodiversity and Climate Change in the Nordic Region

- 2.1.1. Peatlands

- 2.1.2. Forests

- 2.2. Approach and methodological considerations

- 2.2.1. Biodiversity

- 2.2.2 Climate

- 2.3. International policy agreements

- 2.3.1. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

- 2.3.2. The Conventions on Biodiversity and Climate Change

- 2.3.3. Other global agreements and science-policy platforms

- 2.3.4. The European Union

- 2.3.1. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

- 3. Synergy between biodiversity and climate regulation

- 3.1. Peatlands

- 3.2. Forests

- 4. Nordic Policy options

- 5. Introduction to case studies

- 6. Case studies

- 6.1. Restoration of one of the largest raised bogs in lowland northwest Europe, Denmark

- 6.2. Restoration of natural landscape hydrology - mire restoration, Sweden

- 6.3. Palsa mires – a threatened sub-arctic habitat, Norway

- 6.4. Future land use options in peatlands with abandoned forestry, Finland

- 6.5. Natural regeneration of temperate deciduous forests, Norway

- 6.6. Restoration of an almost extinct forest ecosystem, Iceland

- 6.7. Doubling the area of forest set aside biodiversity for conservation, Denmark

- 6.8. Development of biodiversity and carbon storage in ancient boreal forests, Sweden

- 7. Acknowledgement

- References

- About this publication

MENU

Synergy in conservation of biodiversity and climate change mitigation in Nordic peatlands and forests

– Eight case studies

Synergy in conservation of biodiversity and climate change mitigation in Nordic peatlands and forests. Eight case studies.

Lars Dinesen1

Anders Højgård Petersen2

Carsten Rahbek1,2

IPBES in Denmark

Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate

Nordic Council of Ministers

Contents

Executive summary

We are facing two global environmental crises, the loss of biodiversity and climate change. Both crises should be handled within the forthcoming decades if not to develop beyond our control. Actions implemented to mitigate one challenge should not worsen the other, and solutions that address both at the same time are preferable. To some extent, the two crises are interlinked. Biodiversity, together with geophysical and climatic factors form and maintain ecosystems, which contribute to climate change mitigation by capturing CO2 and store carbon. On the other hand, the current climate change worsen the negative impact of the main drivers causing biodiversity loss, i.e., land use change, non-sustainable use of natural resources, invasive species and pollution. This leads to further degradation of ecosystems, which in turn may weaken the functionality of ecosystems that may reduce the ability of nature to capture and store carbon.

The United Nations sustainable development goals (SDGs) outline the urgent need to combat climate change and protect and restore biodiversity and ecosystems. The coming decade is declared The United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. Nature-based solutions are increasingly invoked to meet the range of objectives necessitated by restoration. Nature-based solutions however require informed decision-making and long-term planning. These context-specific approaches can offer transformative change but require stakeholders to learn from existing practices and develop consensus around best practices for a range of different situations. Key examples demonstrating positive outcomes for both biodiversity and climate can support larger scale objectives and policies.

Case studies

The project identified eight cases related to nature-based solutions enacted in the Nordic countries of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. The report assess results and identifies potential synergies between biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation.

Four case studies describe projects involving Nordic peatlands while the other four cases describe initiatives related to forests. Across the cases, synergies have been identified and defined as initiatives, which conserve and restore biological intactness of ecosystems and at the same time reduce the emission of greenhouse gases and/or accumulate and store carbon in these ecosystems.

Two peatland cases from Denmark and Sweden represent active and ongoing restoration of the hydrology and biological communities of degraded mires. A third case study from Norway examines the degradation of an entire peatland ecosystem, the Palsa mires. This unique habitat type faces the risk of complete extirpation due to climate change. The fourth peatland case from Finland describes research on future land-use of drained and afforested boreal peatlands no longer under commercial / economic valuation.

Two forest case-studies from Iceland and Norway examine the potential for restoring native deciduous forest ecosystems that have been cut down and converted primarily to agricultural use. Both studies focus on areas capable of natural or assisted regeneration in abandoned landscapes with minor human management. A third case from Denmark describes a government initiative to restore natural forests in Danish state lands. This case explores the process for designating future conservation areas to be abandoned by forest industry after initial restoration of conditions necessary for reintroducing biodiversity. A fourth case from Sweden presents research on boreal forests on how boreal forests accumulate organic carbon in tree biomass and soil. The development of biological communities, in long term undisturbed ecosystems of different age classes spanning several thousand years can enhance biodiversity and climate change mitigation goals.

Synergy

Tables 3.1 and 3.2 list synergies between biodiversity and climate mitigation objectives realized by the eight projects as well as literature sources that further describe these synergies.

Intact mires comprise a unique set of biological communities of varying diversity, which will be negatively affected if the biophysical and chemical conditions change. Peatlands moreover represent massive accumulations of organic carbon buried and stored in the form of soils that often extend several meters below the surface and have accumulated over thousands of years. Drainage of mires deteriorate biodiversity and cause emissions of CO2 from decomposition of the carbon stock. In terms of their climatic effects, these emissions carry the same risks and long-term costs to society as those produced by fossil fuel combustion.

Restoration of natural hydrology in drained peatlands typically produces immediate benefits in the form of an overall reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (expressed as the combined fluxes of CO2, CH4, N2O and DOC). Even in cases with substantial initial methane (CH4) emissions, the long-term climate benefits of rewetting drained peatlands (restoring natural water balance and flows) exceed those of maintaining drainage systems. Biodiversity will slowly recover in hydrologically restored mires, but the pace of recovery strongly depends on the degree of degradation and the new conditions.

For forests, consensus holds that natural undisturbed (primary) forests and other old growth forests host the most intact biodiversity. Thus, both conservation of such forests and nature restoration in previously managed forests benefit biodiversity. Conversely, forestry (commercially managed forest) entails negative impacts on biodiversity to varying degrees depending on the specific management practices. Forests influence climate both in terms of the carbon stock stored by the forest ecosystems in biomass and soil and through the uptake of CO2 from the atmosphere by photosynthesis in trees in particular. Thus, forests can mitigate climate change by maintaining the accumulated natural carbon stock or by increasing the stock (carbon sequestration) when younger trees and stands grow older.

Preservation and restoration of nature is essential for biodiversity and in combating climate change. Well-functioning ecosystems provides habitats for species, accumulate and store large amounts of carbon, and provide other ecosystem services such as recreational opportunities for humans (e.g., time spent in nature). The Convention on Biological Diversity, the Convention on Climate Change and the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 list protecting and restoring peatlands and old growth forests as target objectives. These recently include allocating 30% of the land to nature protection by 2030 and phasing out net greenhouse gas emissions in all sectors by 2050. With their strong commitment to evidence-based approaches, high rates of educational attainment, economic resources, and willingness to collaborate in taking on grand challenges, the Nordic countries can not only achieve these goals but also provide leadership in demonstrating how to meet them. Monitoring and documenting progress towards targets and modelling adaptive approaches will be crucial in managing these global risks.

Policy options

The report concludes with ten policy options (see chapter 4 for details).

1. Restoring nature, as exemplified in this report, provides an excellent option for Nordic countries to align with and take lead in meeting international biodiversity and climate policy targets through nature-based solutions.

2. A stop for new drainage activities in mires is essential to preserve natural carbon stocks and conserve biodiversity.

3. Nordic countries can prevent emissions of carbon dioxide and initiate long-term biodiversity restoration by rewetting drained mires and peatlands including areas currently used for farming, forestry or peat excavation.

4. Strict protection of existing old growth forests by the exclusion of forestry will safeguard important biodiversity and contribute to climate change mitigation through the preservation of natural carbon stocks.

5. Restoration of forest ecosystems allowing them to develop towards natural old growth forests is essential to biodiversity conservation and contributes to climate change mitigation and ecosystem resilience.

6. Conservation actions in managed forests can be a supplementary option, which is significantly less effective for preserving biodiversity, but with the potential to obtain or retain the possible climate benefits and economic return from forestry.

7. Improved documentation of the greenhouse gas dynamics and biodiversity of intact and restored ecosystems, preferably at the same location, is essential to develop informed and efficient nature based solutions and strategies.

8. Planning at large spatial scales will increase the efficiency and facilitate both local and overall synergies between biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation.

9. Enhanced national mechanisms to provide advice and communicate results of scientific research on biodiversity and climate change will improve decision-making and public debate

10. Ambitious cross-sectorial and cross-disciplinary policies can facilitate the wider use of cost-efficient nature-based solutions to meet the biodiversity and climate challenges.

List of Acronyms

| CAP | EU Agricultural Policy |

| CBD | Convention on Biological Diversity |

| CH4 | The chemical formulae for methane |

| CO2 | The chemical formulae for carbon dioxide |

| DOC | Dissolved Organic Carbon |

| EU | European Union |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| IPBES | Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| IUCN | International Union for Nature Conservation |

| LBII | Local Biodiversity Intact Index |

| LULUCF | Land Use and Land Use Change and Forestry |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contribution |

| NorBalWet | Nordic Baltic Wetlands Regional Ramsar Initiative |

| N2O | The chemical formulae for nitrous oxide |

| PREDICTS | Projecting Responses of Ecological Diversity In Changing Terrestrial Systems |

| RIS | Ramsar Information Sheet |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNEP | United Nations Environment Programme |

1. Introduction

We face two interrelated global crises the loss of biodiversity and climate change (IPBES 2019, IPCC 2019). The UN’s sustainable development goal (SDG; https://sdgs.un.org/goals) no. 13 addresses the urgent need to arrest and manage climate change. SDG no. 15 seeks to protect biodiversity and restore ecosystems on land (see also UNEP 2019). World leaders including those representing Nordic countries have committed to these goals. Biodiversity and climate change are interdependent phenomena whose myriad connections are often scientifically conceptualized as feedback systems. On the one hand, species form ecosystems that perform natural carbon sequestration, cycle atmospheric gases, and form the base of the food chain through primary productivity. On the other, climate change in the form of rising temperatures and shifting weather patterns on larger times scales can disrupt food sources and destabilize habitats. These pervasive and large-scale impacts of climate change are a major driver of biodiversity loss after land use and direct exploitation of species (IPBES 2019). Nature-based solutions to preserve biodiversity can also mitigate climate change primarily through enhanced carbon storage but also through uptake over time.

Approaches to managing changes in precipitation, severe storms, and sea level rise can also involve nature-based solutions that enhance biodiversity (e.g., restoration of coastal dunes or other habitats) or adaptation to situations of increased flooding etc. While broader integrated approaches or adaptation measures are critical examples of synergies, they lie outside the scope of this report.

Nature-based solutions are typically implemented at national and local levels. Bodies and institutions operating at these levels will make decisions and carry out specific initiatives. Cohesive action requires instantiation on political grounds and geographical scales. These problem spaces have so far proved intractable in terms of meeting biodiversity targets over the last two decades (IPBES 2019). Missed opportunities have produced an even more urgent need to demonstrate by example that targets can be met. Specific cases of success or positive developments for biodiversity and climate will encourage more and coordinated action.

The concept of nature-based solutions is still under development. The concept has been put forward by practitioners (in particular the International Union for Nature Conservation, IUCN) and quickly thereafter by policy (European Commission), referring to the sustainable use of nature in solving societal challenges. The definition by IUCN is below (see also Eggermont et al. 2015).

Nature-based solutions as defined by IUCN 2021

Nature-based Solutions are actions to protect, sustainably manage and restore natural and modified ecosystems in ways that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, to provide both human well-being and biodiversity benefits. They are underpinned by benefits that flow from healthy ecosystems and target major challenges like climate change, disaster risk reduction, food and water security, health and are critical to economic development. https://www.iucn.org/theme/nature-based-solutions/about

Recent climate and biodiversity reports have emphasized the importance of local action (IPBES 2019, IPCC 2019) but national level leadership is also critical. Among other nations, Nordic governments not only acknowledge the risks of biodiversity loss and climate change they also possess the imperatives to address these issues with effective action. Factors contributing to consensus on reducing risk arise from a societal tradition of evidence-based approaches, high educational attainment levels, strong cultural and social institutions, and adequate economic resources.

Peatlands and forests are particularly important for both biodiversity and climate regulation due to their ability to sequester and store carbon and for their biodiversity. These eight cases take departure in either of these two ecosystems, which in some cases overlap. The project promotes the use of knowledge on synergetic solutions, and it will hopefully inspire and support Nordic leadership at the interface between biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation including for example the use of nature-based solutions feeding into nationally determined contributions (see also IUCN 2019).

2. Background

2.1. Biodiversity and Climate Change in the Nordic Region

Peatlands and forests are shaped by climate and are important for regulation of climate because they uptake and store carbon. Peatlands represent one of the largest terrestrial reservoirs of carbon on Earth and have residence times of hundreds or thousands of years (see below). Carbon is also stored in the biomass of trees and some peatland soils are covered by trees and the two ecosystems overlap in time and space.

The number and abundance of species and both genetic and ecosystem diversity have increased in Nordic regions since the last ice age. This can be attributed to natural factors such as the gradually immigration of plants and animals into the barren land after the ice (Hallanaro & Pylvänäinen 2001).

The region is rich in biodiversity and spans from temperate regions in the south over the boreal region to tundra in the arctic regions in the north and thus represents an immense range in climate and geophysical parameters. However, in a global perspective the Nordic region generally hosts more widespread species and a lower biodiversity compared to most tropical regions. Never-the-less Nordic biodiversity is important in our daily lives and as a contribution to overall global biodiversity. The human effect on biodiversity and landscapes have increased dramatically over the last several thousand years and especially during the last couple of centuries human driven biodiversity loss has taken place in the Nordic region (Hallanaro & Pylvänäinen 2001) as well as globally (IPBES 2019) both in genetic diversity as well as species and ecosystem level (see e.g. cases presented here).

Nordic biodiversity has been described in a number of publications for example Hallanaro & Pylvänäinen (2001). Here the focus is on two widespread Nordic ecosystems namely peatlands and forests. IPBES (2018) describes the global loss of biodiversity and soil organic carbon. Nordic research in the areas of land degradation and restoration can therefore inform approaches to large-scale problems.

2.1.1. Peatlands

Peatlands are wetlands with a high content of organic carbon. Mires are peatlands with a living biological community accumulating peat. Mires host native Nordic biological communities, which include a number of unique species and species interactions. Peatland forms in areas of excessive moisture where waterlogged conditions prevent the complete decomposition of plant material. The distribution and character of peatlands therefore strongly depends on climate (Barthelmes et al. 2015). Tab. 2.1 lists estimates of mire and peatland area among Nordic countries (Joosten et al. 2017).

| Country | Mire area km2 | Peat area km2 | Country area km2 | Criteria |

| Denmark | 137 | 2,029 | 43,000 | |

| Finland | 35,000 | 90,000 | 338,000 | > 0 cm peat |

| Iceland | 2,112 | 5,777 | 103,000 | > 12% organic carbon |

| Norway | 37,700 | 44,700 | 324,000 | |

| Sweden | 52,300 | 63,700–69,200 | 450,000 |

Tab. 2.1. The area of mire (peatland with actively growing natural vegetation) and of total peatland area (including degraded organic soil) in Nordic countries. Differences primarily reflect differences in total land area and the degree of drainage conducted in the respective countries. Source: Joosten et al. 2017.

Peatlands are found throughout the Nordic region. In the subarctic and arctic zone peatlands are influenced by permafrost and polygon and palsa mires comprise peatland types influenced by permafrost. In the boreal zone peatlands cover vast areas comprising Aapa mires in areas with a positive water balance where cool conditions limit evapotranspiration including in areas with low precipitation (Barthelmes et al. 2015). In the temperate zone in south peatlands are found as raised bog and fens in areas with exceeding rainfall and in basins with ground water flow (see below).

Mires are often classified as ombrotrophic and minerotrophic mires depending on whether they receive their nutrients and water from rain or from streaming or ground water (Joosten in press.). Thus, in ombrotrophic mires the peat layer is thick and have often been accumulated for hundreds or thousands of years and are fed by rain. These mires are acid and nutrient poor and usually covered by a thick layer of Sphagnum mosses usually known as bogs including raised bogs and blanket bogs. In the minerotrophic mires the layer of peat is usually thinner and they are fed by streaming water and/or groundwater to various degrees as well as precipitation (Fig. 2.1) and known as fens. A great variety of intermediate mires exists and they are also influenced by nutrients and minerals, e.g. rich or poor fens depending on the classifications.

The plant community is often used to define the mire types. A thorough assessment of this diversity based on vegetation and characteristic species in Europe is presented in (Joosten et al. 2017), which include country chapters for all the Nordic countries. Mires are generally species poor compared to for example forests, but they nevertheless host unique and protected biological communities (see also chapter 2.3. on policy agreements).

Fig. 2.1. Schematic diagrams of different types of bogs and fens. Bogs receive nutrients from the air while fens are largely fed by ground water. Transitional mires are largely influenced by rainfall but can also receive ground water input. Source: Joosten (in press., Ramsar Convention on Wetlands).

Various species of Sphagnum mosses usually predominate in Nordic mires. These mosses cover the surface of many mires while dead plant material covered by water below surface gradually transitions into peat. Sphagnum is important because their cells are capable of absorbing large amounts of water and thereby contribute to keep a high-water table (Joosten in press.). Few vascular plants live in mires (there are exceptions) due to the acidic and often nutrient poor conditions. Invertebrates include e.g. nematodes, mites, spiders, ants, beetles and other insects. Mires also play an important in the life cycles of aquatic insects such as mosquitos, horse-flies, and black flies (Hallanaro & Pylvänäinen 2001). Their considerable biomass attract e.g. insect-eating birds.

Peatlands play an important role in global climate regulation and constitute the largest terrestrial store of carbon (Parish et al. 2008, Barthelmes et al. 2015). Mires act generally as net carbon sink removing CO2 from the atmosphere by photosynthesis while at the same time emitting CH4. However, in the long-term accumulation of carbon takes place. Drainage of mires releases large amounts of CO2 and sometimes N2O (Barthelmes et al. 2015) that act as greenhouse gasses (GHGs).

The large carbon stock is comprised of layers of peat under waterlogged conditions accumulated over centuries or millennia (Fig. 2.2). Most originated at the onset of the Holocene and have accumulated peat and thereby bound large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere for the past 10,000 years.

Fig. 2.2. Cross section of a mire (raised bog) showing the peat column. b) Peat accumulation over time, and c) net gain of peat showing litter (dead vegetation) accumulation in excess of decomposition. Illustration from Page & Baird (2016) in Bartlett et al. 2020.

In addition to climate, hydrological and hydro-chemical factors determine rates of carbon accumulation in peatlands. Nutrient rich fens typically exhibit higher rates of accumulation. The rates generally increase in nutrient rich fens and decrease with nutrient poor conditions.

In peatlands the dead plant material is subject to aerobic decay only for a limited time because it soon arrives in a permanently waterlogged and oxygen poor environment where the rate of decay is an order of magnitude lower (Barthelmes et al. 2015). Thus, a high-water table is essential for climate regulation because lowering the water table results in decomposition of the plant material due to access of oxygen and the release of CO2 and N2O turning drained peatlands into carbon sources. Peatlands are roughly GHG neutral when the mean water table level is in the range of 0 to 10 cm below the surface (Barthelmes et al. 2015, Bartlett et al. 2020) and become emitters when inundated due to release of CH4.

In Nordic regions, large areas of peatland have been drained primarily for agriculture, forestry, or peat extraction. In the region as a whole, about 44% of the peatlands have been drained. This exceeds the global average of 12% but falls below the percentage of degraded peatlands estimated for the whole of Europe of 60%. However, there are large variations among the Nordic countries: Denmark has drained about 93% of its peatlands, Finland has drained 78%, Iceland 63%, Sweden 18% and Norway 9% (Barthelmes et al. 2015).

The climate burden of degraded peatlands

Whereas natural peatlands have been cooling the global climate over the last 10,000 years, drained and degraded peatlands are powerful sources of carbon dioxide (CO2) and nitrous oxide (N2O). These greenhouse gases (GHGs) result from microbial oxidation of organic matter when air penetrates the formerly water-saturated peat. The drier conditions following drainage also increase the risk of fire (Kettridge et al. 2015, Sirin et al. 2020).

The emissions from peatland exploitation, degradation and fires are currently responsible for some 5% of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Continuing emissions from drained peatlands until 2100 may comprise 12–41% of the remaining GHG emission budget for keeping global warming below +1.5 to +2 °C (Leifeld et al. 2019). Further scenario studies indicate that the global land sector will by 2100 be a net carbon source, unless all presently intact peatlands remain intact and at least 60% of the currently degraded peatlands are in the coming decades rewetted (Humpenöder et al. 2020). This implies, that with rewetting ‘only’ 60% of the degraded peatlands, the carbon sink capacity of the entire remaining land sector (af- and reforestation, improved forest management, carbon sequestration in mineral soils) will merely serve to compensate for the carbon losses from the remaining 40% of degraded peatlands and will not contribute to the ‘net carbon sinks’ (cf. IPCC 2018).

Modified after Joosten (in press.).

2.1.2. Forests

Forest once covered most of the Nordic region south of the arctic and below tree lines. Today, more than 650,000 km2 of forest cover more than half of the land area of Sweden and Finland and more than a third of the land area of Norway (Framstad et al. 2013). However, most Nordic forest has been subject to major human alteration beginning in southerly regions approximately 6000 years ago (Berglund 1991, Myhre & Øye 2002; both cited in Framstad et al. 2013 and Fritzbøger & Odgaard 2017). These impacts include logging for wood or agricultural clearing such that few old growth or primary forests remain. Denmark and especially Iceland have been virtually entirely deforested. Today, Denmark has restored the forest cover of about 15% of its land area (about 6000 km2 Nord-Larsen et al. 2019) while Iceland’s forest cover is still only a few percent or about 1500 km2 (Snorrason et al. 2016).

Most Nordic forests categorized as boreal coniferous forests (taiga) dominated by the native species Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and Norway spruce (Picea abies) (Hallanaro & Pülvänäinen 2001). Temperate, or “nemoral”, broadleaved deciduous forests occur scattered throughout southern Norway and occur more widely distributed in southern Sweden. These also formed the predominant native forest types of Denmark. Common native tree species include the Beech (Fagus sylvatica), the Oaks (Quercus robur) and (Q. petraea), the Ash (Fraxinus excelsior), the Maple, (Acer platanoides), and the Lime (Tilia) spp. (Hallanaro and Pülvänäinen 2016). Mountain birch forms a unique type of forest in the northernmost regions between the boreal coniferous forest and the arctic tundra (Hallanaro and Pülvänäinen 2016). These forests host a unique variety of Downy birch, (Betula pubescens), and represent the only native woodland and scrub habitats found in Iceland (e.g., Aradottir et al. 2013).

Vast and variegated natural forests formed by climatic, geological and biological factors occupied the Nordic region over hundreds of thousands of years between Pleistocene ice ages. These natural forests thus comprise the habitats to which most Nordic species are evolutionarily adapted. However, apart from the mountain birch woodlands, the vast majority of forests found in Nordic regions today, are typically managed for wood production (e.g., Framstad et al. 2013). Forest management, including widespread clear-cutting, has significantly reduced the natural biodiversity.

Forest management entails reduction and alteration of many specific habitat types found in natural undisturbed forests. In managed forests, trees in each stand are typically uniform in terms of species, size, and age. Understory vegetation is actively removed. Old trees and deadwood are missing because trees are typically harvested at a biologically young age. Clearcutting is common practice (removing all trees at once) particularly in coniferous forests. Management practices also include soil treatment prior to planting the next generation of trees. Together these practices represent major disturbances, which are not comparable to the dynamics of natural forest ecosystems. Drainage of moist and wet soils to promote tree growth are also widespread, and in some regions, fertilizer is applied. All these practices substantially reduce and alter the natural heterogeneity and dynamics that create habitats and sustain biodiversity in natural forests (e.g., Berg et al. 1994, Christensen & Emborg 1996, Paillet et al. 2010, Müller & Bütler 2010, Rudolphi & Gustafsson 2011, Lelli et al. 2018).

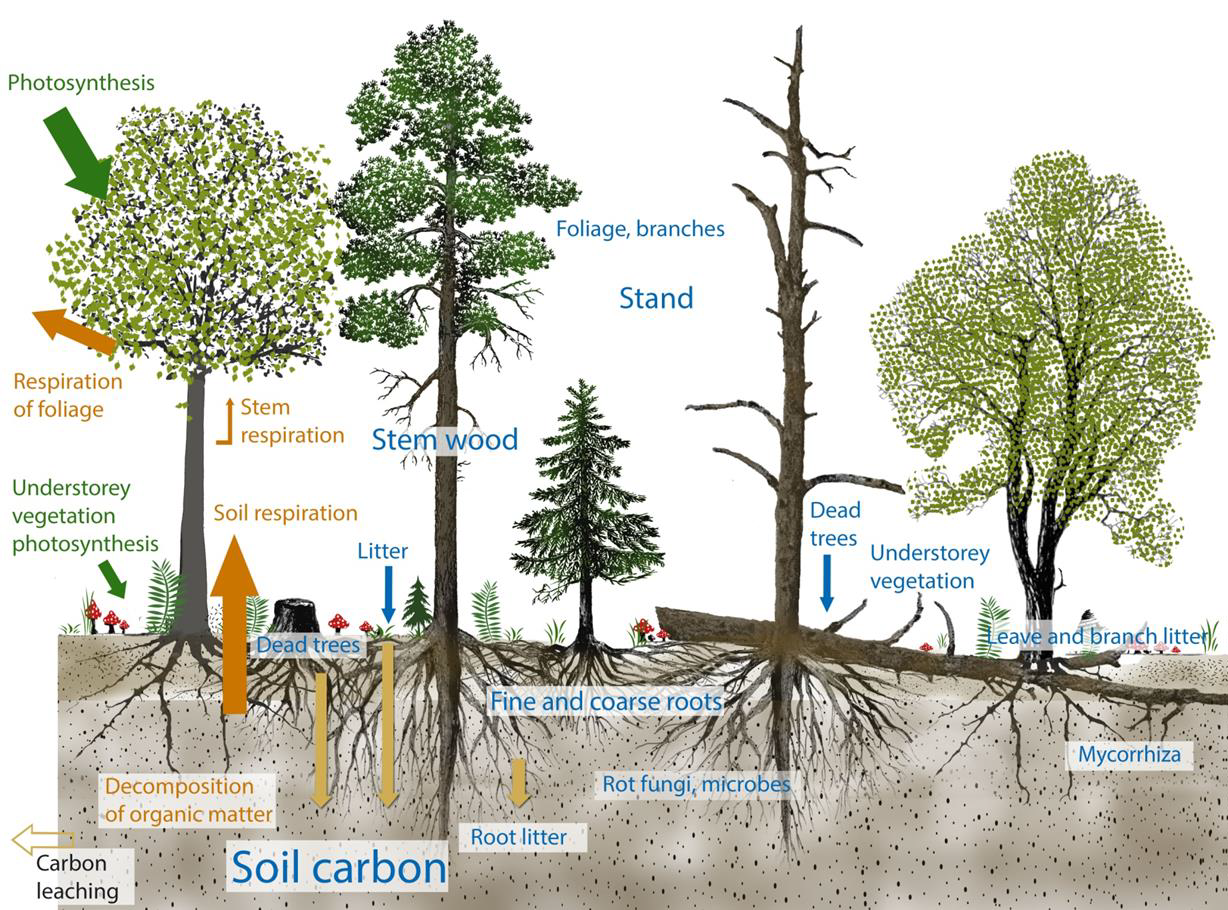

Nordic forests not only sustain regional biodiversity, they also regulate climate. Forest ecosystems perform a number of fluxes in the terrestrial carbon cycle including absorbing and storing major fractions of carbon. Trees take up CO2 and convert it into carbon stored in standing trees, understory vegetation, litter, dead wood, and soil. Therefore, forest ecosystems represent some of the most important natural carbon sinks and carbon stores, both globally and in the Nordic region. Fig. 2.3 shows typical forest carbon cycle processes. Different types of forests behave differently in terms of carbon sinks and fluxes. In addition to climatic conditions, soil type, and forest age, the dominant tree species also influence carbon cycle dynamics. Young forests accumulate carbon faster than old forests but old forests hold larger stocks of carbon.

Fig. 2.3. The carbon cycle of the forest ecosystem. Source: Onarheim (2018, Mires and Peat, 24, art. 27).

Commercial forestry, including logging, soil treatment, and drainage, strongly influences the carbon cycle and carbon stocks stored by forests. The carbon stock of a managed forest is usually smaller than that found in natural old growth forests because trees are smaller due to frequent harvest (Harmon et al. 1990, Ciais et al. 2008, Mäkipää et al. 2011). Furthermore, understorey vegetation and dead wood are kept at lower proportions. Harvesting especially by clearcutting often reduces the soil carbon stock (e.g., Peltoniemi et al. 2004, Häkkinen et al. 2011). Drainage also reduces soil carbon and leads to higher CO2 emissions from the forest due to higher rates of decomposition of accumulated organic material like peat (e.g., Ojanen & Minkinen 2019, IPCC 2014). Some circumstances mitigate the climatic impacts of managed forests. Harvested wood products from managed forests contribute to climate mitigation by substitution of fossil fuels and building materials that require more fossil fouel for their production, and through carbon storage in wood products (Sathre et al. 2010, Leskinen et al. 2018). However, researchers and policy makers continue to debate the relative merits of forest conservation versus management for wood production in terms of their respective climatic impacts (e.g., Searchinger et al. 2018, Taeroe et al. 2017, Nabuurs et al. 2017).

Overall, protection of existing old growth forests and restoration of natural forest ecosystem represents important opportunities for conservation of biodiversity and mitigation of climate change. A thorough assessment of the “Biodiversity, carbon storage and dynamics of old Northern forests” with focus on the Nordic region is given in Framstad et al. (2013). Fig. 2.4. gives an overview of greenhouse gas fluxes in a forest ecosystem.

Fig. 2.4. Mass transfer components and CO2, CH4, and N2O fluxes contributing to soil carbon stock and fluxes in a forest ecosystem subject to drainage as in IPCC (2014). Source: Jauhiainen et al. (2019).

2.2. Approach and methodological considerations

The identification and description of eight case studies to illustrate potential synergy between biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation is the primary aim of this report. Moreover, focus was limited to a few key ecosystems in order to bring forward related cases, and thereby consolidate findings and provide more robust policy advice. A focus on wetlands and forests was chosen because both ecosystems constitute important natural carbons stocks and host important and threatened biodiversity. Thus, a focus on only two main ecosystem types was prioritized over including e.g. marine ecosystems (“blue carbon”) such as seagrass beds or other wetland types. Finally, our focus is mainly on climate change mitigation rather than adaptation.

The specific case studies were selected based on criteria, which included the need for evidence from scientific research, monitoring or other relevant studies and ideally on both biodiversity and climate at the same time. Moreover, an opportunity to learn from the case was essential. Thus, there should be a story and information from the case to share of general Nordic interest. Finally, a geographical balance within the Nordic region is needed to cover a range of different habitats and contexts within the two selected ecosystems. Eventually, four peatland and four forest cases were identified in five Nordic countries: Denmark, Iceland, Finland, Norway and Sweden. For all cases, key persons in the respective countries were contacted and meetings were held with scientific researchers and government officials. The relevant persons are mentioned in the acknowledgement sections in each case study.

It has been a general challenge to identify cases with substantial evidence on both climate and biodiversity. With a few exceptions, more comprehensive studies were conducted within one of these two fields. To meet the need for national cases of great regional interest, cases at very different geographical scales were included, ranging from just one locality in one case to restoration of ecosystems at national or even regional level in other cases.

2.2.1. Biodiversity

One of the definitions of biodiversity used by IPBES (2020) is:

The variability among living organisms from all sources including terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are a part. This includes variation in genetic, phenotypic, phylogenetic, and functional attributes, as well as changes in abundance and distribution over time and space within and among species, biological communities and ecosystems.

This is a slight change from the definition used by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which was defined twenty years earlier:

“Biological diversity" means the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems.

Thus, a stronger focus on variations in time and space is introduced as well as variation at the genetic level and of functional attributes and generally a somewhat more dynamic concept.

It is difficult to provide an all-encompassing measure of biodiversity in the field situation and in that regard, biodiversity is different from measuring climate change. However, our overriding assumption is that intact ecosystems are important for biodiversity as well as for functions and processes. Moreover, it is our assumption that intact ecosystems are important for biodiversity at the three levels of its definition i.e. for genetic diversity, for species diversity (including abundance) and for ecosystem diversity.

In this report we primarily focus on biodiversity at habitat and ecosystem level, although assessment of indicator species is included as well in some cases. We have a focus on native biological communities including their functions and biological processes, which primarily have developed in our region after the last ice age. It has been the aim to focus on functional ecosystems and habitats supporting biological processes and interactions and, in that way, promote individual species and biological communities and thereby, also genetic diversity.

One emerging field in this regard is the work with biological intactness in relation to what has been lost due to human impact (Scholes & Biggs 2005, Newbold et al. 2015), which at the moment use species as surrogates for biodiversity. Newbold et al. (2015) states: Human activities, especially conversion and degradation of habitats, are causing global biodiversity declines. How local ecological assemblages are responding is less clear—a concern given their importance for many ecosystem functions and services. These attempts have recently turned their focus into local diversity and move away from global measures such as the total species extinction because resilience of ecosystem functions and services are likely to depend on local diversity (Newbold et al. 2015).

The models by Newbold et al. (2015) suggested that land-use changes and associated pressures strongly reduce local terrestrial biodiversity e.g. in peatlands and forests and including species richness at different scales and total abundance (Newbold et al. 2015, see also IPBES 2019). In other words, such work moves towards estimating how much of a terrestrial site's original biodiversity remains. These assessments are based on a specific “Local Biodiversity Intactness Index” (LBII), for background information see Newbold et al. (2015), Hudson et al. (2016): https://www.predicts.org.uk/pages/policy.html .

Because the local biodiversity intactness index (LBII) relates to site-level biodiversity, it can be averaged and reported for any larger spatial scale (e.g., countries, biodiversity hotspots or biomes as well as globally) without additional assumptions. However, they still rely to a large degree on species richness data in a database: PREDICT (Hudson et al. 2014).

We have used the general assumption that intact ecosystems with an original assemblage of species and their interactions comprise a baseline where biological functions and processes are preserved. We have used the general assumption that the preindustrial state of an ecosystem would seem to be the most ideal reference condition, and that this could be approximated in practice by contemporary data from minimally impacted sites (see e.g. Purvis et al. 2018) and acknowledging that ecosystems with its assemblages of biological communities are constantly evolving and not a steady state.

There is no comprehensive or complete biodiversity studies in any of the Nordic cases presented in this report. Biodiversity intactness is still an emerging biological discipline, which underlines the challenge of identifying a generally accepted “currency” for measuring biodiversity, which is also relevant at the local level.

Moreover, a common aim in recent biodiversity management is the move towards restoring (or conserving existing) self-regulatory habitats and ecosystems with a need for limited or no human interventions (Barfod et al. 2020 as an example from Denmark). This will often require larger areas set aside for nature.

2.2.2 Climate

Research in carbon cycles including flux and emissions of greenhouse gas is perhaps one of the most rapid developing research fields at the global level. Measuring fluxes at local sites (e.g. An & Zong 2016) or presenting regional or global reviews is developing fast. Nevertheless, it has been difficult to find cases in the Nordic countries with comprehensive field studies involving greenhouse gas flux monitoring and carbon stock measures, which also has comprehensive information on biodiversity (see cases chapter 6).

Certainly, one of the most important reasons for peatland rewetting and restoration is climate change mitigation (Griscom et al. 2017). Although peatland restoration initially has been targeted biodiversity restoration in the Nordic region, the climate benefits from certain biodiversity restoration projects have become increasingly clear within the last decade (e.g. Barthelmes et al. 2015). This is because the huge emissions of greenhouse gasses from drained peatlands can be significantly reduced by raising the water levels closer to the ground level. The more exact level of the water table needed to have the maximum effect depends on the specific context and the peatland type (Joosten in press.).

The water level is key to the climate impact from a peatland. In the drained situation, there will be significant greenhouse gas emissions. The deeper the water table, the larger the emissions (Joosten in press.). With water table at the ground – the case in many natural peatlands – the balance between different greenhouse gasses becomes more delicate. With a high water table – as in the natural state – there is an accumulation of organic material over time and the emission of CO2 is almost zero. In an intact mire or a rewetted peatland, the accumulated plant material (peat) is decomposed anaerobically (without oxygen) resulting in the emission of CH4, a greenhouse gas 28 times stronger than CO2. However, in general, rewetting of drained peatlands instantly leads to benefits: The overall greenhouse gas effect (expressed as the combined fluxes of CO2, CH4, N2O and DOC) becomes positive for the climate, compared to the former drained situation and the carbon sink function is being restored (Nugent et al. 2018, Joosten in press.).

Even in case of a large initial methane peak, the longer-term climate effects of rewetting are better than maintaining the drained status quo. The reason is that CH4 has a shorter atmospheric lifetime compared to CO2 and N2O, which actually accumulate in the atmosphere, whereas the atmospheric concentrations of CH4 quickly reach a steady state (Joosten in press., Fig. 2.5.).

Fig. 2.5.: Radiative forcing (RF) and global climatic warming effects (relative to 2005) of peatland management without (left) and with (right) an initial 10 times larger methane peak for 5 years after rewetting. Drain_More: The area of drained peatland continues to increase from 2020 to 2100 at the same rate as between 1990 and 2017; No_Change: The area of drained peatland remains at the 2018 level; Rewet_All_Now: All drained peatlands are rewetted in the period 2020–2040; Rewet_Half_Now: Half of all drained peatlands are rewetted in the period 2020–2040; Rewet_All_Later: All drained peatlands are rewetted in the period 2050–2070. Source: Günther et al. (2020). Nature Communications 11:1644.

Global Warming Potential

Global warming potential (GWP) is a relative measure of how much heat a greenhouse gas traps in the atmosphere. It compares the amount of heat trapped by a certain mass of the gas in question to the amount of heat trapped by a similar mass of carbon dioxide. GWP is calculated over a specific time interval, commonly 20, 100 or 500 years. GWP is expressed as CO2-equivalents (CO2-e) i.e. as a factor of carbon dioxide (whose GWP is standardized to 1). Source: Barthemeles et al. (2015).

Often, there is no specific flux measurements of GHG at a site or in a given habitat. In this case an assessment may rely on standard emission factors from the IPCC guidance (IPCC Wetlands Supplement 2014) applying the use of standard values using the IPCC guidelines on emissions (2006). However, these standard figures are generally intended for indicative national inventories only, and not for detailed locality specific studies, which means that there is a large degree of uncertainty in these calculations. Site-specific measurements are preferable.

2.3. International policy agreements

A number of international policy agreements are relevant for the policy options provided in this report (chapter 4).

2.3.1. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are 17 interlinked global goals set in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly. The three Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of particular relevance for biodiversity and climate in peatlands and forests are stated below. These goals come with a set of related targets and indicators specifying the goals into more concrete measurable actions and the most relevant are indicated below. The timeline for some targets has unrealistically been set to 2020, as these follow the Aichi Targets to be met in 2020, however, as they have not been met (IPBES 2019), activities for their fulfillment must be expected to continue for the time being. New targets are under development as part of the Post Biodiversity Framework (CBD 2020).

Goal 15 - Life on Land: Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss.

Target 15.1: By 2020, ensure the conservation, restoration and sustainable use of terrestrial and inland freshwater ecosystems and their services, in particular forests, wetlands, mountains and drylands, in line with obligations under international agreements. Indicator 15.1.1: Forest area as a proportion of total land area. Indicator 15.1.2: Proportion of important sites for terrestrial and freshwater biodiversity that are covered by areas, by ecosystem type.

Target 15.2: By 2020, promote the implementation of sustainable management of all types of forests, halt deforestation, restore degraded forests and substantially increase afforestation and reforestation globally. Indicator 15.2.1: Progress towards sustainable forest management.

Target 15.5: Take urgent and significant action to reduce the degradation of natural habitats, halt the loss of biodiversity and, by 2020, protect and prevent the extinction of threatened species. Indicator 15.5.1: Redlist index.

Goal 13 - Climate action: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

Target 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning. Indicator 13.2.1: Number of countries that have communicated the establishment or operationalization of an integrated policy/strategy/plan which increases their ability to the adverse impacts of climate change, and foster climate resilience and low greenhouse gas emissions development in a manner that does not threaten food production (including a national adaptation plan, nationally determined contributions, nationally communication, biennial update report or other).

Goal 6 – Clean water: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all

Target 6.5: By 2030, implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate. Indicator 6.5.1: Degree of integrated water resources management implementation (0–100)

Target 6.6: By 2020, protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests, wetlands, rivers, aquifers and lakes. Indicator 6.6.1: Change in the extent of water-related ecosystems over time

Moreover, peatlands and forest ecosystem restoration providing synergy between biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation provides for related services and benefits supporting various of the other interdependent sustainable development goals and targets.

2.3.2. The Conventions on Biodiversity and Climate Change

The Convention on Biological Diversity and the post 2020 biodiversity targets are under development and presently in draft form, however, the COVID-19 has postponed the COP15, which was supposed to agree on biodiversity targets for the next decade. The EU has a vision of taking a leading role in the development of the post 2020 biodiversity agenda hence the EU biodiversity strategy (June 2020) is of relevance in this regard (see below).

The Aichi Targets for biodiversity set for 2020 have unfortunately not been met. A thorough assessment was conducted as part of the global report from IPBES (2019) concluding that it was unlikely to meet most of these targets. They included globally agreed targets relevant for biodiversity in peatlands and forests including for example:

Target 5: The rate of loss of all natural habitats, including forests, is at least halved and where feasible brought close to zero, and degradation and fragmentation is significantly reduced.

Target 11: At least 17% of terrestrial and inland water, and 10% of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.

Target 12: The extinction of known threatened species has been prevented and their conservation status, particularly of those most in decline, has been improved and sustained.

Target 15: Ecosystem resilience and the contribution of biodiversity to carbon stock have been enhanced, through conservation and restoration, including restoration of at least 15% of degraded ecosystems, thereby contributing to climate change, mitigation and adaptation and to combat desertification.

The Paris agreement from 2015 under the convention sets the target in 2050 of no net emission of greenhouse gasses and with the aim to limit global warming to 1.5 to 2 degrees C above pre-industrial levels. The Paris Agreement enables countries to deliver on their national climate action plans under the Paris Agreement (“Nationally Determined Contributions”, or “NDCs”), thereby promoting further ambitions to tackle climate change over time.

Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) are at the heart of the Paris Agreement and the achievement of these long-term goals. NDCs embody efforts by each country to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. All Parties are requested to submit the next round of NDCs (new NDCs or updated NDCs) by 2020 and every five years thereafter.

For the land-use, land-use change and forestry sector, emissions and removals the following reporting categories are included: forest land, cropland, grassland, and wetland (wetland remaining wetland only from 2016), including land use changes between the categories, and between these categories and settlements and other land. The five carbon pools above-ground biomass, below-ground biomass, litter, dead wood and soil organic matters are included. In addition, the carbon pool harvested wood products is included.

The current submission is based on the IPCC Guidelines 2006 combined with the emission factors from the 2013 Wetlands Supplement (IPCC 2014) Chapter 2 and 3 for CO2, N2O and CH4 combined with national derived emission factors. The LULUCF sector differs from the other sectors in that it contains both sources and sinks of carbon dioxide.

2.3.3. Other global agreements and science-policy platforms

IPCC i.e. the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was created as an independent scientific body to provide policymakers with regular scientific assessments on climate change, its implications and potential future risks, as well as to put forward adaptation and mitigation options.

IPCC 2019:

While some response options have immediate impacts, others take decades to deliver measurable results. Examples of response options with immediate impacts include the conservation of high-carbon ecosystems such as peatlands, wetlands, rangelands, mangroves and forests. Examples that provide multiple ecosystem services and functions, but take more time to deliver, include afforestation and reforestation as well as the restoration of high-carbon ecosystems, agroforestry, and the reclamation of degraded soils

A wide range of adaptation and mitigation responses, e.g., preserving and restoring natural ecosystems such as peatland, coastal lands and forests, biodiversity conservation, reducing competition for land, fire management, soil management, and most risk management options (e.g., use of local seeds, disaster risk management, risk sharing instruments) have the potential to make positive contributions to sustainable development, enhancement of ecosystem functions and services and other societal goals

IPBES i.e. the Intergovernmental platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services provides global and regional assessments to strengthen the science-policy interface and provide scientific information on biodiversity and related ecosystem services (Natures Contribution to People) including climate regulation for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, long-term human well-being and sustainable development. Eight comprehensive assessment reports have so far been produced reviewing thousands of papers related to biodiversity including an assessment of the before mentioned Aichi Targets.

The reports states that biodiversity loss is accelerating and that we are degrading land in terms of for example loss of organic carbon soil and native species and that less than one quarter of the land surface is now wilderness with intact ecological and evolutionary processes. However, one of the key findings in the reports is that it is still possible to change the course but a transformative change is needed if we are going to succeed in bending the curve of biodiversity loss as has been global targets to be met since 2010. This implies according to IPBES (2019) changes in all dimensions of life including changing economic, social, political and technological factors.

A number of other relevant conventions exist for example the Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar), which has been instrumental in the conservation and wise use of peatlands. The Nordic countries have played a key role in this regard through common statements and various resolutions on peatlands through the Nordic Baltic Wetlands cooperation – a regional initiative under the Ramsar Convention comprising the Nordic and the Baltic states. Moreover, the history and recognition of peatlands as important for biodiversity and climate is apparent from the historical development of the convention (Barthelmes 2015). The first mentioning was in 1996: “Conservation of peatlands”. At the Conference of the Parties in 1999 was the first acknowledgement of the importance of peatlands in climate change mitigation. In 2008 new resolutions confirmed that peatlands were the most important carbon store on land. The role of CH4 as a greenhouse gas was for the first time stated in a 2012 resolution. The Convention continues to have a strong focus on peatlands and their biodiversity and the link to climate change.

The United Nations Forum on Forest carries out a number of outreach activities to raise awareness of the multiple benefits of forests, and share best practices related to sustainable forest management. Work, is undertaken on the reporting on progress towards the implementation of the UN Strategic Plan for Forests 2030 and the UN Forest Instrument. At the heart of the Strategic Plan are six Global Forest Goals and 26 associated targets to be achieved by 2030. These include Goal 1: “Reverse the loss of forest cover worldwide through sustainable forest management, including protection, restoration, afforestation and reforestation, and increase efforts to prevent forest degradation and contribute to the global effort of addressing climate change.” And Goal 3: “Increase significantly the area of protected forests worldwide and other areas of sustainably managed forests, as well as the proportion of forest products from sustainably managed forests.”

Moreover, the Council of Europe’s Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (1979), or Bern Convention, was the first international treaty to protect both species and habitats and to bring countries together to decide how to act on nature conservation. Working on climate change mitigation through biodiversity solutions. The convention forms the basis for the Emerald Network in Norway and Iceland and it was the frontrunner of the two EU directives on nature i.e. the Birds and Habitats Directive.

2.3.4. The European Union

The EU has recently launched some rather ambitious plans directed by the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen as indicated in one of her statements in 2020: “Making nature healthy again is key to our physical and mental wellbeing and is an ally in the fight against climate change and disease outbreaks. It is at the heart of our growth strategy, the European Green Deal, and is part of a European recovery that gives more back to the planet than it takes away."

The European Green Deal deals with climate change and environmental degradation, which are seen as an existential threat to Europe and the world and with a vision to develop a new growth strategy that will transform the Union into a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy, where: 1) there are no net emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050, 2) economic growth is decoupled from resource use, 3) no person and no place is left behind and by a vision for turning climate and environmental challenges into opportunities.

The EU biodiversity Strategy for 2030 was launched in June 2020 by the EU Commission 2020 and its objectives endorsed by the Council of the EU in October. The strategy outlines biodiversity targets for the EU including an EU Nature Restoration Plan with a series of specific commitments and actions to restore degraded ecosystems across the EU by 2030, and manage them sustainably, addressing the key drivers of biodiversity loss. Of the 25% of the EU budget dedicated to climate action, a significant proportion is stated in the strategy to be invested in biodiversity and nature-based solutions as a mean to reduce GHG emissions. Furthermore, 30% of the land area should be protected and 10% strictly protected for biodiversity and with strict protection of the remaining primary and old-growth forests in the EU member states and with potentially legally binding nature restoration targets in 2021. Specifically, primary and old-growth forests are mentioned as the richest forest ecosystem that removes carbon from the atmosphere, while storing significant carbon stocks. Significant areas of other carbon-rich ecosystems, such as peatlands, grasslands, wetlands, mangroves and seagrass meadows should also be strictly protected, taking into account projected shifts in vegetation zones.

The two EU nature directives the Birds and Habitat Directives cover a large number of peatland and forest types categorized as habitat types or habitats for certain species and thereby protected by the directives. Habitat types under the Habitat Directive include raised bog, aapa and palsa mires, old broad-leaved deciduous forest and various types of temperate Beech forest to mention some examples included in the case studies. The Bird and Habitat directives are the cornerstone for the EUs nature conservation policy for the designation of Natura 2000 sites in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. Generally, the peatland and forest habitats in the Nordic EU countries are in an unfavorable conservation status according to the EU reporting in 2019.

Moreover, the Water Framework Directive plays an important role in the protection of inland surface and ground waters and to restore good ecological status including a high-water quality. In the Nordic countries there is a general need to reduce the N and P pollution in water courses and lakes in order to meet the requirements of the directive. The directive explicit refers to the restoration of wetlands, which includes rewetting of peatlands. The EU Agricultural Policy (CAP) is important for the land use in EU including the Nordic EU countries. The CAP includes the EUs largest subsidy scheme involving hundreds of billion euros for agricultural support under pillar I and II. The second Pillar focus on environmental sustainability and climate and will be increasingly relevant for providing incentives for restoration measures in peatlands and forests.

The EU 2030 climate policy framework includes the LULUCF (Land Use, Land Use Change and Forest) Regulation (Romppanen, 2020), which concerns carbon pools in above-ground biomass, below-ground biomass, litter, dead wood, soil organic carbon, and harvested wood products in the land accounting categories of afforested land and managed forest land. In contrast to previous EU law, where emissions from use of biomass in energy production were not accounted, the LULUCF Regulation does include biomass for energy production: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/forests/lulucf_en. EU Forestry Policy.

3. Synergy between biodiversity and climate regulation

The assessed synergy from different management options and their effects on biodiversity and climate, is provided in Tab. 3.1 and 3.2.

The two tables summarize our assessments based on general scientific knowledge as well as input from the eight case studies (presented in chapter 6). Here we elaborate on the rationale behind these assessments and discuss synergies in this context. These considerations do also form a basis for the assessments of synergy in the eight case studies although cases differ in the level of details and type of information.

The overall assessment of synergy between biodiversity conservation/restoration and mitigation of climate change follows a simple colour codex of green (yes), orange (depends) and red (no). The green colour indicates synergy. Red colour indicates no synergy because either biodiversity or climate or both do not benefit from the management and the orange colour indicate that synergy is context specific and depends on a specific situation or the assumptions set for the assessment and/or calculations.

Guiding towards the assessment of synergy is the effect on biodiversity and climate assessed separately and following a colour codex. Here the greenish colour indicate strong positive effect on biodiversity or climate from a given action and the reddish colour a strong negative effect. A positive effect is being graduated as strong (green) or weak positive (light green) as well as strong (red) or weak (light red) negative. Orange depends on the chosen baseline or the kind of climate effect.

The effect on the climate is split in 1) the effect on the preservation of the carbon stock (or tree biomass) and 2) the effect on carbon uptake and sequestration by the plants (see Tab. 3.1 and 3.2 for the results).

3.1. Peatlands

Synergy between biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation is identified when drained peatlands are restored by rewetting and reestablishment of natural hydrological conditions. This can be achieved by blocking ditches, cutting down trees or building dams (Joosten in press., Dinesen & Hahn 2019) to secure water in the peatland and avoid drainage to the surrounding land, which is often drained agricultural land or managed forests. Rewetting of the organic soil stops the emission of CO2 and restores the conditions, which are the foundation for unique biological communities in mires. Rewetting all types of peatlands creates synergy. This ranges from living peatlands, also called mires, to cultivated organic soils, which have lost their original biological communities. Living peatlands slowly build up carbon stocks, which entails a long-term climate benefit, although their greenhouse gas balance is often rather close to zero and they may act as both sources or sinks over time.

Restoration with no active interventions may yield positive results in certain cases for example in old poorly drained boreal peatlands where forestry is abandoned. Synergy actually may develop without human intervention because the old ditches created for forestry slowly fills in resulting in a gradually rise in water table, which is good for the climate because it prevents the aerobic decomposition of organic material and resulting emissions of CO2. At the same time biodiversity will benefit from increasingly wet conditions and the abandoned wood production, which mean that fertilizer is not added and discontinued logging mean that a burst of these nutrients to the water is also prevented. The synergy in nutrient poor peatlands will be largest from no interventions while for example nutrient rich fens will have larger emissions and synergy will be dependent on restoring a high-water table as soon as possible to stop CO2 emissions. Hence, a flexible approach at landscape level will provide the largest opportunities for creating synergy because it depends on the specific setting of the individual peatland.

On the other hand, no intervention in abandoned agricultural peatlands or existing agriculture on organic soil for that matter extend the negative effect on climate due to the emission of CO2. At the same time biodiversity is maintained and not being restored due to a lack of water and a heavily degraded state. The introduction of paludiculture i.e. crops on wet soil or in water is the only solution to change this negative impact. Paludiculture will benefit climate per definition (see Wichtmann et al. 2016), however, the benefit for biodiversity may dependent.

Agriculture and forestry on peat soil has negative effects on biodiversity compared to the more pristine situation. Generally, both activities also negatively affect climate, although in some cases the effect of forestry may be debated (see below). Peat excavation is usually dependent on drainage and is directly devastating for biodiversity and climate because of drainage and even more so when the peat is used for energy. In that regard using peatlands as a source of energy is nothing better than using fossil fuels, however, the biological communities are lost as well when energy comes from peat.

Tab. 3.1. Overview of the expected effects of different peatland management options on biodiversity and climate, and the possible synergies. The effect on climate (column 5) is the combination of the carbon stock and uptake and emission of GHGs (column 3 and 4). The specific effects are briefly described in each cell. Colour legend are given below. See text for further explanation.

| Legend, effects: |

| Strong positive effect |

| Weak positive effect |

| Depends on chosen baseline or the kind of climate effect |

| Weak negative effect |

| Strong negative effect |

| Legend, synergy: |

| Yes |

| Depends |

| No |

| Management option | Effect on | Synergy between biodiversity and climate | |||

| Biodiversity | Carbon/CO2 (+ methane, CH4) | Climate | |||

| Stock (In ecosystem) | Uptake and emission (including sequestration) | ||||

| Conservation of intact mire system (pristine peatland) (Case studies #1,# 2,#3, #4) | High biodiversity is conserved | The large carbon stock is preserved and slowly increases | Uptake low, some years may even be negative but exceeds GHG emission from the mire in the long-term | The large carbon stock is preserved. Accumulation of carbon in the long-term | Important for biodiversity and effectively stored carbon |

| Restoration of a mire ecosystem (active peatland with natural vegetation) by rewetting and e.g. removal of exotic trees. (Case studies #1,#2, #4) | Biodiversity is conserved and increases | The (remaining) large carbon stock is preserved and slowly increases | Significant emission of CO2 decreases or stops. CH4 increases. Uptake low but continue in the long term | The remaining large carbon stock is preserved. GHG emissions reduced, at least in the long-term. Accumulation of carbon may restart. | Important for biodiversity and effectively stored carbon |

| Restoration of degraded peatland without natural peat communities by rewetting and e.g. facilitation of spaghnum growth (Case studies #1, #4) | Biodiversity increases, but only slowly, especially for demanding species | The (remaining) carbon stock is preserved | Significant emission of CO2 decreases or stops. CH4 increases. Uptake low or zero but may build up in the long-term | The remaining carbon stock preserved. GHG emission reduced at least in the long-term. | Yes. But effects may be slow for biodiversity and for climate it depends on size of carbon stock left. |

| No restoration intervention on poorly drained boreal peatlands with semi-natural vegetation on abandoned forestry land (Case study #4) | May benefit biodiversity, but slow recovery and speed of development of biological communities may depend on e.g. water quality | The remaining carbon stock may be preserved due to natural rise in water level but nutrient rich peatlands may be emitters | Some sequestration from planted trees and, in the long term, from recovered peat due to increase in water level | The remaining carbon stock preserved depending on nutrient status. GHG emissions reduced due to increase in water level. | Slow recovery of biodiversity compared to restoration scenario and preserved carbon stock dependent on specific setting |

| Mainstream forest management on peatsoil including drainage and use of fertilizer (Case studies #2, #4) | Biodiversity reduced and changed | Stock reduced from natural level | Uptake increased by forestry, but may be be counterbalanced by emissions from peat decomposition | Stock decreases, but wood production may entail climate benefits | No |

| Conventional agriculture on organic soil (peatsoil) (Case study #1) | Biodiversity markedly reduced and changed | Stock continues to deterioate for a long time unless changed to paludiculture | Emission large | The carbon stock decreases and emission continues unless changed to paludiculture | No |

| Peat excavation (Case studies #1, #4) | Biodiversity destroyed | Stock destroyed | Emission large | Stock decreases and with large emissions | No |

3.2. Forests

Most importantly, we identify synergies between biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation with both conservation of natural old growth forests and restoration of (more) natural forest ecosystems in deforested areas or managed forests. These synergies are discussed below and further documented in the case studies. For biodiversity, the basic assumption is that natural undisturbed old growth forests (i.e. unmanaged forest) with a broad array of natural habitats host the highest and most important biodiversity including the highest richness of rare species. For biodiversity at species level, this is well documented in the field (e.g. Berg et al. 1994, Christensen & Emborg 1996, Paillet et al. 2010, Müller & Bütler 2010, Rudolphi & Gustafsson 2011, Lelli et al. 2019). However, it also lies in the fact that natural ecosystems per se are important elements of biodiversity according to the general definitions by CBD and IPBES as outlined above. It is also well-established that logging, and forestry and commercial forest management in broader terms, entails negative impacts on biodiversity, although the magnitude depends on the specific management practices (cf. the references above). In accordance with the above, both preservation of old growth forests and schemes allowing managed forest to develop towards natural old growth forests is widely accepted as important and effective biodiversity conservation measures (Crouzeilles et al. 2016, Lindenmayer et al. 2006).

The climate mitigation effects are derived from two components: The ecosystem carbon stock (in biomass and soil) and the net uptake of CO2 from the atmosphere and storage of carbon (carbon sequestration). It is well established that the carbon stocks are generally larger in natural old growth forest than in a managed production forest where trees are on average younger and smaller due to logging (Harmon et al. 1990, Ciais et al. 2008, Mäkipää et al. 2011). Thus, there is a clear climate benefit from protecting old growth forests because large natural carbon stocks are effectively preserved and CO2 is kept out of the atmosphere. This also means that forest reserves in previously logged forests typically entails carbon sequestration when wood is no longer harvested and (more) natural carbon stocks build up (e.g. Allen et al. 2016, Braun et al. 2016). On the other hand, as mentioned before, the harvest of wood products in managed forests may contribute to climate mitigation by substitution of fossil fuels and energy-intensive materials like concrete and steel, but also through the storage of carbon in buildings and long-lived wood products (Sathre et al. 2010, Leskinen et al. 2018).

It is currently highly debated as also mentioned before, whether forest conservation or management for wood production entails the largest climate benefits (e.g. Searchinger et al. 2018, Taeroe et al. 2017, Nabuurs et al. 2017). The answer to this strongly depends on the time perspective and numerous other assumptions including the expected development within forest management and in several other sectors. Examples are the future efficiency of timber production, the use of wood for construction and developments within emission-free energy sources such as wind and solar energy. This uncertainty is indicated with orange marking of the relevant cell in Tab. 3.2. Concluding on this issue is beyond the scope of this study. We limit our assessment to the facts that there are clear climate benefits associated with restoring (more) natural forest ecosystems in previously managed forests.

We also identify synergies associated with afforestation, i.e. planting or natural regeneration of forest in previously non-forested or deforested areas. Thus, afforestation will almost inevitably entail carbon sequestration wherever it is implemented (increase of carbon stocks), and climate benefits may also arise from harvested wood products in the long term. Afforestation on farmland or degraded land will most often also benefit biodiversity in the long term, but the magnitude and nature of these effects will depend on the geographical context and very much on the future management. For example, natural hydrology should always be restored in drained areas. On the other hand, afforestation on natural open habitats like grasslands, heathlands and bogs entails no synergy. Although it might benefit the climate (if no drainage is applied), the associated changes of the natural biodiversity must be regarded as a negative impact.

Hence, the orange cells in Tab. 3.2 indicate that the assessment of effects or synergies and trade-offs depends on the context, the assumptions or the baseline, i.e. the state of the forest with which the management scheme in question is compared. An example of the latter is implementation of conservations actions in managed forest, which might entail positive effects on biodiversity, while forestry as such still negatively affects the biodiversity. Another example is the assumption concerning carbon sequestration: Are old growth forest carbon sinks in general, and for how long does the ecosystem carbon sequestration continue in a forest after logging is stopped? This is also debated and subject to further research. Yet another example is the above question, whether managed or unmanaged forest best mitigate climate change. Further research and implementation of demonstration projects are needed.

Tab. 3.2. Overview of the expected effects of different forest management options on biodiversity and climate, and the possible synergies. The effect on climate (column 5) is the combination of the carbon/CO2 stock and uptake (column 3 and 4). The specific effects are briefly described in each cell. Colour legend are given below. See text for further explanation

| Legend, effects: |

| Strong positive effect |

| Weak positive effect |

| Depends on chosen baseline or the kind of climate effect |

| Weak negative effect |

| Strong negative effect |

| Legend, synergy: |

| Yes |

| Depends |

| No |

| Management option | Effect on | Synergy between biodiversity and climate | |||

| Biodiversity | Carbon/CO2 | Climate | |||

| Stock (In ecosystem) | Uptake (sequestration and harvest) | ||||

| Conservation of old-growth forest (Case studies #6, #7, #8) | High biodiversity is conserved | The large stock is preserved | Uptake low or zero | Carbon stock is preserved. But no or only little gain | Yes. But most important for biodiversity |

| Restoration forest ecosystem (From managed forest to old-growth in the long term) (Case study #7) | Biodiversity is conserved and increases | Stock increases (sequestration) | Uptake decreases over time, possibly towards zero | Ecosystem stock increases (and is larger than without forest), but climate benefits from wood production is lost | Yes. But for climate, only in terms of ecosystem carbon stock |

| Restoration through reforestation (Natural regrowth or planting. Old growth in the very long term (Case studes # 5, # 6) | Biodiversity increases, but only slowly, especially for demanding species | Stock increases (sequestration) | Uptake increases, but decreases again in the long term | Stock increases | Yes. But effects are slow, especially for biodiversity |