- Full page image w/ text

- Authors

- Table of contents

- Preface from project managers

- Preface from pillar coordinators

- Summary

- Chapter 1 Comparative perspectives on non-standard work in the Nordics: definitions and overall trends

- Chapter 1 Comparative perspectives on non-standard work in the Nordics: definitions and overall trends

- 1.1 Introduction: Non-standard work in the Nordics

- 1.2 Non-standard work – types and recent development across the Nordic labour markets

- 1.2.1 Part-time work in the Nordics – types, development and sector variations

- 1.2.2 Temporary employment in the Nordics – types, development and sector variations

- 1.2.3 Solo self-employment

- 1.3 Nordic non-standard workers and their characteristics

- 1.4 Methodological challenges and alternative studies on emerging forms of non-standard work

- 1.5 Main findings – cross-country and sector variations in non-standard work

- Chapter 2 Regulating non-standard work in the Nordics – opportunities, risks and responses

- 2.1 Introduction

- 2.2 Risks and opportunities associated with non-standard work

- 2.2.1 Risks of in-work poverty

- 2.2.2 Income insecurity (underemployment)

- 2.2.3 Job insecurity

- 2.2.4 NSW and its opportunities

- 2.3 Regulating non-standard work in the Nordics

- 2.3.1 Regulating temporary employment – fixed-term work and TAW

- 2.3.2 Regulating part-time work

- 2.3.3 Solo self-employment

- 2.4 Recent national debates and social partner responses to non-standard work

- 2.4.3 Emerging forms of non-standard work – solo self-employment and platform work

- 2.4.4 A European minimum wage and the directive on transparent and predictable working conditions

- 2.5 Main findings and perspectives

- 2.4.1 Part-time work – involuntary, contracts of few hours and gender inequality

- 2.4.2 Temporary employment – job insecurity and social dumping

- Traditional forms of non-standard work – mapping country developments via Labour Force Survey data

- Chapter 3 Non-standard work in Sweden

- 3.1 Background

- 3.2 Introduction and status

- 3.3 Sectoral variation across different employment types

- 3.4 Worker characteristics

- 3.4.1 Involuntary non-standard work

- 3.5 Regulation of non-standard work in Sweden

- 3.6 Policy debates and reforms

- 3.6.1 Involuntary part-time work and work life balance

- 3.6.2 Temporary employment and job (in)security

- 3.6.3 Temporary agency work

- 3.6.4 Solo self-employed workers and unclear definitions

- 3.7 Alternative surveys, studies and data sources

- 3.8 Summary and conclusions

- Chapter 4 Non-standard work in Denmark

- 4.1 Background

- 4.2 Introduction and status

- 4.3 Sectoral variations in non-standard work

- 4.4 Worker characteristics

- 4.5 Debates and policy responses

- 4.5.1 Regulation of non-standard work in Denmark

- 4.5.2 Risks in non-standard work

- 4.5.3 Policy responses from government and social partners

- 4.6 Methodological reflections

- 4.6.1 Alternative ways to measure non-standard work

- 4.7 Summary and conclusions

- Chapter 5 Non-standard work in Norway

- 5.1 Background

- 5.2 Introduction and status on non-standard work

- 5.3 Sectoral variations in non-standard work

- 5.4 Worker characteristics

- 5.5 Debates, regulations and policy responses in Norway

- 5.5.1 Regulation of non-standard work in Norway

- 5.5.2 Debates and policy responses to non-standard work

- 5.5.3 Labour market attachment, social security and involuntary non-standard work

- 5.6 Additional research and alternative data sources

- 5.6.1 Temporary agency work

- 5.6.2 Self-employed

- 5.7 Methodological challenges

- 5.8 Summary and conclusions

- Chapter 6 Non-standard work in Finland

- 6.1 Background

- 6.2 Introduction and status

- 6.3 Sectoral variations in forms of non-standard work

- 6.4 Worker characteristics

- 6.5 Regulation of non-standard work in Finland

- 6.6 Policy debates and reforms

- 6.6.1 Solo self-employment and their status

- 6.6.2 Part-time work

- 6.7 Alternative surveys, studies and data sources

- 6.8 Summary and conclusions

- Chapter 7 Non-standard work in Iceland

- 7.1 Background

- 7.2 Introduction and status

- 7.3 Sectoral differences in forms of non-standard work

- 7.4 Worker characteristics

- 7.5 Regulation of non-standard work in Iceland

- 7.6 Development, research and debate

- 7.7 Alternative data sources

- 7.8 Methodological challenges

- 7.9 Summary and conclusions

- Emerging trends in non-standard work: case studies in selected sectors

- Chapter 8 The hotel and restaurant sector in Denmark and Finland

- 8.1 Introduction

- 8.1.1 The collective bargaining system in Denmark and Finland

- 8.1.2 Introducing the two case companies

- 8.2 Case 1: A Danish conference hotel

- 8.2.1 Brief background information and methods

- 8.2.2 Collective bargaining model: Company based agreements and cooperation

- 8.2.3 Types of non-standard work – emerging employment forms

- 8.2.4 Wage and working conditions: Differences in sectoral agreements

- 8.2.5 Health and safety issues

- 8.2.6 Brief summary – Danish hotel case

- 8.3 Case 2: A large hotel chain in Finland

- 8.3.1 Brief background information and methods

- 8.3.2 Collective bargaining model at the company

- 8.3.3 Non-standard is the new standard

- 8.3.4 Non-standard work: You win some, you lose some

- 8.3.5 A good work environment - inclusion of non-standard workers?

- 8.3.6 Health and safety issues: Same work, different benefits?

- 8.3.7 Brief summary of the Finnish hotel case

- 8.4 Comparing country cases

- 8.4.2 Flexible sector in need of skilled workers – hires flexible workers

- 8.4.1 Main types of non-standard work: Outsourcing and uncertain hours

- 8.4.3 The need for further studies: Cases and methods

- 8.4.4 Conclusion and discussion

- Chapter 9 Freelance companies in Norway and Sweden

- 9.1 Introduction

- 9.1.1 Freelance companies vs. other contractual forms of work

- 9.1.2 Introducing the two case companies

- 9.2 Case 1: The Norwegian freelance company

- 9.2.1 Background

- 9.2.2 Description of the studied company and the informants

- 9.2.3 Type of contracts and working conditions

- 9.2.4 Health and safety issues and social events

- 9.2.5 Union representation and collective wage agreement

- 9.2.6 Advantages and disadvantages

- 9.2.7 Conclusions, implications and future perspectives

- 9.3 Case 2: The Swedish freelance company

- 9.3.1 Background

- 9.3.2 Description of the case company and interviewees

- 9.3.3 Advantages and possibilities

- 9.3.4 Disadvantages and challenges

- 9.3.5 Collective agreements

- 9.3.6 Conclusions, implications and future perspectives

- 9.4 Comparing country cases – companies for freelancers

- 9.4.1 Which groups are the companies targeting?

- 9.4.2 What does the employment entail?

- 9.4.3 An affiliation that gives contractors more job security in the future labour market?

- Chapter 10 Eldercare in Sweden and Denmark

- 10.1 Introduction

- 10.1.1 Characteristics, developments and challenges in the eldercare sector

- 10.1.2 Non-standard work within the eldercare sector – in Sweden and Denmark

- 10.1.3 Regulation and organisation: The collective bargaining system

- 10.1.4 The case studies

- 10.2 Case 1: Eldercare in Sweden

- 10.2.1 Introduction: the case and the study

- 10.2.2 Types of non-standard work

- 10.2.3 Rationale behind the use of the different employment forms

- 10.2.4 Wage and working conditions

- 10.2.5 Issues of health, safety and well-being

- 10.2.6 Summary of the Swedish eldercare case

- 10.3 Case 2: Eldercare in Denmark

- 10.3.1 Introducing: the case and the study

- 10.3.2 Types of non-standard work

- 10.3.3 Rationale behind the use of the different employment forms

- 10.3.4 Wages and working conditions

- 10.3.5 Health, safety and wellbeing issues

- 10.3.6 Summary of the Danish eldercare case

- 10.4 Comparing country cases

- 10.4.1 Tendencies of non-standard work

- 10.4.2 Rationales, challenges and possibilities

- 10.4.3 Conclusion, discussion and future perspectives

- Chapter 11 Summary of case studies and policy responses

- 11.1 Comparative perspectives on case studies

- 11.1.1 The flexible firm

- 11.1.2 The worker’s perspective

- 11.2 Comparative perspectives on policy responses

- Chapter 12 Covid-19: Non-standard work in times of crisis

- Chapter 12 Covid-19: Non-standard work in times of crisis

- 12.1 Introduction

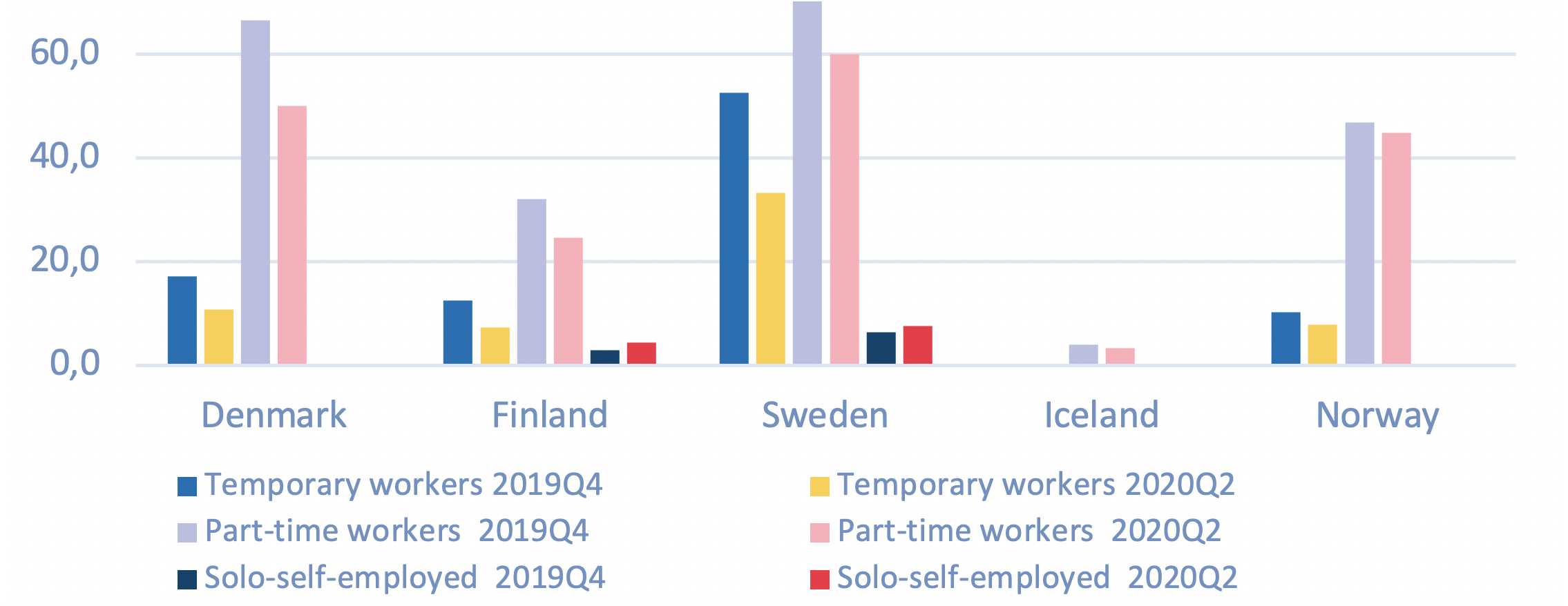

- 12.2 The corona crisis and its effects on Nordic labour markets and non-standard workers

- 12.3 The Nordic governments’ help- and relief packages aimed at non-standard workers

- 12.3.1 Denmark

- 12.3.2 Norway

- 12.3.3 Finland

- 12.3.4 Iceland

- 12.3.5 Sweden

- 12.4 The effects and the associated challenges of the Nordic government’s help- and relief packages for non-standard workers

- 12.5 Main findings and comparative perspectives

- Chapter 13 Conclusion and perspectives

- 13.1 Concluding points – troubled waters under the still surface

- 13.2 The future of non-standard work in the Nordics - are we all going to be non-standard workers and can the Nordic model adjust?

- References

- Atypisk beskæftigelse i Norden - kontinuitet og forandring

- About this publication

MENU

Non-standard work in the Nordics

Troubled waters under the still surface

Report from The future of work: Opportunities and Challenges for the Nordic Models

Edited by Anna Ilsøe and Trine Pernille Larsen

In cooperation with

Emma S. Bach

Stine Rasmussen

Per Kongshøj Madsen

Tomas Berglund

Anna Hedenus

Kristina Håkansson

Tommy Isidorsson

Jouko Nätti

Satu Ojala

Tiina Saari

Paul Jonker-Hoffrén

Pasi Pyöriä

Kristine Nergaard

Katrin Olafsdottir

Kolbeinn Stefansson

Arney Einarsdottir

Contents

Preface from project managers

Major changes in technology, economic contexts, workforces and the institutions of work have ebbed and flowed since well before the first Industrial Revolution in the 18th century. However, many argue that the changes we are currently facing are different, and that the rise of digitalised production will entirely transform our ways and views of working. In this collaborative project, funded by the Nordic Council of Ministers, researchers from the five Nordic countries have studied how the ongoing transformations of production and labour markets associated with digitalisation, demographic change and new forms of employment will influence the future of work in the Nordic countries.

Through action- and policy-oriented studies and dialogue with stakeholders, the objective has been to enhance research-based knowledge dissemination and experience exchange and mutual learning across the Nordic borders. Results from the project have informed, and will hopefully continue to inform, Nordic debates on how to contribute to the Future of Work Agenda that was adopted at the ILO’s centenary anniversary in 2019.

The project has been conducted by a team of more than 30 Nordic scholars from universities and research institutes in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. The project started in late 2017 and will be completed with a synthetising report in 2021.

To address the main aspects of change in working life, the project has been organised into seven pillars with pan-Nordic research teams:

- Main drivers of change. Coordinator: Jon Erik Dølvik, Fafo, jed@fafo.no

- Digitalisation and robotisation of traditional forms of work. Coordinator: Bertil Rolandsson, University of Gothenburg, bertil.rolandsson@socav.gu.se

- Self-employed, independent and atypical work. Coordinators: Anna Ilsøe, University of Copenhagen/FAOS, ai@faos.dk; and Trine P. Larsen, University of Copenhagen/FAOS, tpl@faos.dk

- New labour market agents: platform companies. Coordinator: Kristin Jesnes, Fafo, krj@fafo.no

- Occupational health – consequences and challenges. Coordinator: Jan Olav Christensen, National Institute of Occupational Health, Oslo, jan.o.christensen@stami.no

- Renewal of labour law and regulations. Coordinator: Marianne J. Hotvedt, University of Oslo, m.j.hotvedt@jus.uio.no; and Kristin Alsos, Fafo, kal@fafo.no

- Final synthetising report: the Nordic model of labour market governance. Coordinator: Jon Erik Dølvik, Fafo, jed@fafo.no

For Fafo, which has coordinated the project, the work has been both challenging and rewarding. In the final phase of the project, all the Nordic economies were hit hard by the measures taken to slow the spread of Covid-19. This effectively illustrates how predicting the future of work is a difficult exercise.

We are very grateful for all the work done by the team of scholars, and we would also like to thank our contact persons in the Nordic Council of Ministries, namely Tryggvi Haraldsson, Jens Oldgard and Cecilie Bekker Zober, for their enthusiastic support. Many thanks also to all the members of the NCM committees that have contributed to this work through workshops and commenting on different drafts, and to the numerous interviewees in Nordic working life organisations and companies who shared their time and insights with us.

Oslo, 2021

Kristin Alsos, Jon Erik Dølvik and Kristin Jesnes,

Project managers

Preface from pillar coordinators

This report forms part of the large collaborative research project “Future of Work: Opportunities and Challenges for the Nordic Models” (2018–2021) which has been funded by the Nordic Council of Ministers and organised by Fafo, Oslo. The project involves more than 30 researchers from all five Nordic countries and seven subprojects.

This report, “Non-standard work in the Nordics: troubled waters under the still surface”, presents the result of Project Pillar III on non-standard work. Pillar III has focused on both traditional forms of non-standard work (NSW) such as temporary contracts (covering both fixed-term contracts and temporary agency work), part-time, solo self-employed as well as emerging employment practices such as zero-hour contracts and freelancer companies. It involved national research teams from all five Nordic countries (Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland and Iceland). In total, 18 researchers have contributed to the empirical studies and this final report. The Danish team included Anna Ilsøe, Trine P. Larsen and Emma S. Bach (FAOS, University of Copenhagen), Stine Rasmussen and Per Kongshøj Madsen (CARMA, University of Aalborg). The Swedish team included Tomas Berglund, Anna Hedenus, Kristina Håkansson and Tommy Isidorsson (University of Gothenburg). The Finnish team consisted of Jouko Nätti, Satu Ojala, Tiina Saari, Paul Jonker-Hoffrén, Pasi Pyöriä (Tampere University). Kristine Nergaard (Fafo) participated with the Norwegian part of the study, whereas Katrin Olafsdottir (Reykjavik University), Kolbeinn Stefansson (University of Iceland) and Arney Einarsdottir (Bifrost University) formed the Icelandic team.

We would like to thank the Nordic Council of Ministers for financing the project and for helping us finalise this report. Thanks also to Jon Erik Dølvik and Kristin Alsos at Fafo for initiating and organising the project as well as quality assurance. The empirical part of this project has involved more than 60 interviews with social partners, governmental actors, managers, workers etc. Thank you so much for sharing your valuable time with us and allow us to gain insights into the drivers and effects of NSW practices.

Copenhagen, 2021

Anna Ilsøe and Trine P. Larsen

Pillar coordinators

Summary

The Nordic models of labour market regulation and the Nordic welfare states have been built and shaped around the notion of the standard employment relationship, i.e. full-time, open-ended jobs. However, the development of non-standard work (NSW) and emerging practices of new contractual employment forms may challenge these institutions. In the media and academic research, a growing debate has emerged on whether we will all be freelancers or precarious workers in the future labour market – also in the Nordic countries.

In this TemaNord report, we investigate the development of NSW within the context of the Nordic welfare and industrial relations models. We draw on Labour Force Survey (LFS) data from the Nordic Statistical Offices to map the development in traditional, well-known forms of NSW such as fixed-term contracts, temporary agency work, part-time work and solo self-employment. To address emerging employment practices, we conduct in-depth case studies, involving interviews with management and workers in selected and relevant sectors such as hotels and restaurants, freelancer companies and care for the elderly. Finally, we use desk research and elite interviews with representatives from trade unions, employers’ associations and public authorities to uncover policy debates and responses to recent developments in NSW and explore how the Nordic countries have responded to the corona outbreak from the perspective of non-standard workers.

The general statistics demonstrate a fairly stable development in NSW across the Nordics over the last two decades. However, country and sector specific statistics as well as case studies display significant variations and changes beneath the still surface. These differences seem to be highly sector and company specific, but we do not know the exact extent of all of them, as novel practices of NSW are not well-covered by existing surveys and registers. We find interesting examples of policy responses to some of these developments, whereas others are yet to be addressed, not least as the recent corona crisis has revealed some gaps in the Nordic models with regards to non-standard workers’ social- and employment protection. The report concludes with a discussion of what lessons can be learned regarding the development of NSW and the policy measures applied to mitigate undesirable effects not only across the Nordics, but also across sectors and companies.

The report is structured in four parts. The first part, the “Introduction”, consists of two comparative chapters, involving all five Nordic countries (Chapters 1–2). In the second part, “Traditional forms of non-standard work: mapping country developments via Labour Force Survey data”, the recent development in established forms of NSW are analysed for each of the five Nordic countries (Chapters 3–7). The third part of the report, “Emerging trends in non-standard work: case studies in selected sectors”, presents our in-depth case studies of emerging employment practices (Chapters 8–11). The fourth part of the report, “Discussion and conclusion”, discusses the impact of the corona crisis on non-standard workers in the Nordics and the various policy responses of Nordic governments (Chapter 12) and presents the final conclusion and discussion of our findings (Chapter 13). Summaries of single chapters are listed below.

Introduction

Chapter 1 presents a comparative analysis of the development in traditional forms of NSW in Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland and Iceland, using LFS data from the national statistical offices. We focus on four well-known and significant forms of non-standard work: fixed-term contracts, temporary agency work (TAW), long part-time work (15–29 weekly working hours) / marginal part-time work (less than 15 hours per week) and solo self-employment (i.e. people not enrolled in a subordinate employer-employee relationship and without employees, such as freelancers). Around one-third of all people employed in the Nordics can be characterised as non-standard workers, and this figure has remained fairly stable since 2000. However, the forms and scope of NSW vary over time and across countries and sectors. Temporary work (covering fixed-term contracts and TAW) is especially used in Sweden and Finland, whereas solo self-employment is most prevalent in Iceland and Finland. Marginal part-time work is more frequently used in Denmark and Norway, whereas long part-time work has the highest share in Norway and Iceland. Worker characteristics vary across the different forms of non-standard work. Older workers, young people (students in particular), women, and foreign-born persons are more likely to take up part-time and temporary employment, whilst more men, often older workers, pursue a career as solo self-employed in all five Nordic countries. Involuntary NSW has increased in the Nordic countries during the last few decades and is particularly prominent in Sweden, Finland and Norway. Solo self-employment, along with long- and marginal part-time work, are often a voluntary choice for many, while this is less often the case for temporary jobs. Finally, we discuss the methodological challenges in mapping and comparing non-standard work, which can be defined and measured differently across countries. When it comes to categories of NSW such as on-call work, zero-hour contracts and platform work that have emerged or increased in recent years, there are also important differences in definitions. Furthermore, we lack solid and comparable data on these employment practices, which are not mapped consistently and continuously in existing surveys and registers.

Chapter 2 addresses the regulation of NSW in the Nordic countries in the form of labour law, collective agreements and welfare arrangements. We ask the question whether regulations reproduce, reinforce or counteract differences between standard and non-standard work, and highlight relevant policy responses. Firstly, we analyse the risks of in-work poverty, income insecurity in the form of underemployment and job insecurity among non-standard workers, along with the potential opportunities that also may be associated with NSW. Temporary workers are particularly exposed to increased risks of in-work poverty in all five Nordic countries, notably in Norway and Sweden, where almost one in five temporary workers report this. Income insecurity (or underemployment) is highest among marginal part-time workers, especially in Finland and Sweden, where this is the case for one in three of all marginal part-time workers. Job insecurity is highest among temporary workers (fixed-term contracts and TAW) with one in five temporary workers reporting job insecurity in Finland and Sweden. NSW may also in some instances be a stepping stone into the labour market for some groups or a way to retain people in paid work that may otherwise struggle to commit to a full-time job. Secondly, we present an overview of the regulation of NSW in the Nordics. All five Nordic countries have regulations that aim to protect non-standard workers. However, we also find gaps in the regulation when it comes to protection of non-standard workers. Restricted access to unemployment benefits, occupational pensions and insurance as well as underemployment are some of the issues raised in recent debates. Other debates have been closely tied to discussions of social dumping and unfair competition, especially concerning migrant workers within low wage sectors. While the recently adopted EU Directive on Transparent and Predictable Working Conditions may strengthen protection of Nordic non-standard workers – as have former directives regarding equal treatment of temporary and part-time workers – the Commission proposal for introducing a European minimum wage system has been highly contested among the social partners in all five Nordic countries.

Traditional forms of non-standard work in the Nordics

Chapters 3–7 map and analyse developments in NSW in Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland and Iceland, using LFS data from the national statistical offices. Across the Nordic countries, the share of non-standard workers has remained fairly stable since 2000. However, marked cross-country and sector variations can be observed, and we analyse these variations in detail in these country chapters.

In Sweden (Chapter 3), temporary employment is the main – and in recent years increasing – form of non-standard work. Temporary jobs make up 15 per cent of all employment, while the total NSW amounts to 26 per cent. Moreover, temporary employment is increasingly involuntary for workers. Today, 70 per cent of workers with temporary contracts would prefer otherwise in Sweden. This has been associated with a relaxing of the rules regarding temporary contracts in the Swedish labour market, which has allowed Swedish employers to utilise these contracts considerably. Temporary employment is particularly widespread in sectors such as hotels and restaurants (33 per cent), arts and entertainment (30 per cent) and administration and support services (28 per cent). Students, multiple jobholders and people born outside the Nordic countries are overrepresented among temporary workers.

In Denmark (Chapter 4), part-time employment is widespread within the private and public service sectors. Since 2000, the share of long and especially marginal part-time employment has increased. Today, marginal part-time employment is the most common form of NSW in Denmark and accounts for 11 per cent of all employment. The total of NSW is 29 per cent of all employed people. Marginal part-time work is widespread within the hotels and restaurants (32 per cent), arts and entertainment (30 per cent) and retail (24 per cent) sectors. Marginal part-time work is often voluntary – only 5 per cent would prefer full time work. Many marginal part-time workers are students and/or migrants, with 72 per cent reporting school and training activities as their main reason for working marginal part-time jobs.

In Norway (Chapter 5), part-time workers make up the largest group of non-standard workers. Since 2000, long part-time work has decreased while marginal part-time work has increased. However, long part-time work still makes up the largest share of non-standard workers (12 per cent). NSW amounts to 29 per cent of all those employed in Norway. The share of long part-time work is largest in health and social services (23 per cent), hotels and restaurants (20 per cent) and arts and entertainment (16 per cent). Women, young people, older people and multiple jobholders are overrepresented among long part-time workers. Involuntary part-time work (i.e. the number of part-time employees who want longer hours) has decreased during the last two decades and stands at 16 per cent for both marginal and long part-time workers. This might relate to recent legislative measures to fight involuntary part-time work. Nevertheless, being female still increases the risk for involuntary part-time work.

In Finland (Chapter 6), temporary workers (13 per cent) form the largest group within non-standard work, although the number has decreased slightly since 2000. Temporary employment is especially found in sectors such as education (26 per cent) and health (21 per cent). Solo self-employed workers form the second largest group of non-standard workers (10 per cent), which is a relatively high share compared to the other Nordic countries. In total, 31 per cent of all employed people are in a NSW arrangement. In Finland, women, young workers and foreign-born people are overrepresented in non-standard work, but also retirees are likely to undertake TAW or fixed-term work. In addition, temporary positions (including TAW) are often involuntary (two in three would prefer a permanent position). In recent years, solo self-employment and the labour market status and reasons for this type of work have been up for debate.

In Iceland (Chapter 7), long part-time (11 per cent) and temporary work (11 per cent) are the two most dominant forms of non-standard work, whereas solo self-employment comes in third (8 per cent). In total, 31 per cent of all employed people report their employment form as non-standard work. Long part-time work is primarily used in retail, the public sector and within other services, whereas temporary employment is widespread in agriculture, public sector and other services. Solo self-employment is found in agriculture and construction, among others. Employees in NSW are often either young students or older people, close to or at retirement age. Moreover, an increase in foreign workers has led politicians to enact laws that secure their rights, plus an Act on Workplace IDs for sectors with high shares of foreign workers.

Emerging trends in non-standard work: case studies in selected sectors and policy responses

Chapter 8, 9 and 10 present in-depth case studies of emerging practices of NSW in three sectors which are particularly relevant: hotels and restaurants, freelancer companies and care for the elderly. Each study compares two case companies from the same sector, but across two Nordic countries. The analysis is based on interviews with local management, workers and social partners.

Chapter 8 compares two case companies in the hotel and restaurant sector in Denmark and Finland, a sector with highly unpredictable service demands and thus a great need for flexibility. Only one in two workers hold full-time permanent positions within the sector, which is also the case in the companies analysed. The case companies use zero-hour contracts as well as subcontracted work, part-time work and TAW to secure the flexibility needed. In both cases, however, a number of workers without guaranteed working hours are at risk of underemployment, i.e. an insufficient number of hours to make a living, and of falling into gaps in the social protection system. Furthermore, the chapter addresses methodological challenges, when studying contracts without guaranteed working hours. In both Denmark and Finland, social partners have negotiated innovative policy responses to challenges regarding zero-hour contracts. In Denmark, they have agreed upon a higher hourly wage for workers on zero-hour contracts to compensate for their lower levels of social- and employment protection, including lack of guaranteed hours. In addition, we find an innovative chambermaid protocol, which offers employers flexible working time arrangements in return for guaranteeing that minimum 45 per cent of the chambermaids hold full-time positions. In Finland, skiing hotels have negotiated a similar trade-off with the unions by reserving flexible working hours for full-time staff, which encourages employers to hire more full-time employees.

Chapter 9 analyses one freelance company in Norway and one in Sweden, respectively. A freelance company is an organisation which hires freelancers as employees, but at the same time allows them to find their own clients and tasks. The company handles all administrative tasks, such as invoicing and tax/VAT payments. The employed freelancers also get access to social security, i.e. unemployment insurance schemes and sick pay. The Norwegian freelance company hires on open-ended contracts, which is suitable for full-time freelancers with a relatively stable income, who want some of the social security aspects of being an employee. The Swedish freelance company hires on fixed-term contracts and is more similar to a start-up hub, where freelancers on average only stay two years to get a foothold in the labour market as solo entrepreneurs or learn the basics of being self-employed. In both case companies, there is next to no trade union involvement. The Swedish freelance company is member of an interest organisation for freelancer companies in Sweden. In general, solo self-employed and freelancers face increased risks of falling into the social security gaps due to their unclear legal status. In Norway, LO has responded to this by creating ‘LO independent’; a collaboration between trade unions organising self-employed workers under the LO Confederation and offering member services such as legal assistance, courses or discounts on private insurances. In Denmark, the Danish trade union HK has created a similar initiative for freelancers, including a Freelancer Bureau, which employs and assists freelancers with administrative tasks in exchange for a fee. In Iceland, self-employed are obliged to pay to the mandatory pension fund contribution (15.5 per cent of income), that is usually shared by the employer (11.5 per cent) and employee (4 per cent), via the tax system. This initiative ensures that self-employed get similar pensions as employees.

Chapter 10 compares two cases in the Danish and Swedish eldercare sector. In both countries, eldercare is publicly funded and administered by municipalities, although services are increasingly outsourced to private firms. The Swedish case is a private company within eldercare, where workers often are employed on temporary contracts. Within restrained budgets, the main challenge for the employer is to secure staff continuity while at the same time ensuring that flexibility needs are met. This is often resolved by hiring on-call workers and by scheduling with split shifts shared between two or more workers. Similarly in the Danish case, the hiring of part-time and on-call workers is explained by needs for flexibility and cost curbing. Most care workers choose part-time for work-life balance reasons (women are overrepresented in the care sector) and to ease workloads due to the physical and exhausting nature of the work. For the employer, the main challenge with on call work is to secure continuity among staff, whereas many employees struggle to secure a sufficient number of weekly working hours to make a living. To address some of these issues, the social partners in Sweden have signed an interesting agreement on a competence lift, where employees can study to become an assistant nurse while working part-time.

Chapter 11 summaries the comparative case studies of companies as well as policy responses analysed in Chapters 8–10

Conclusion and discussion

Chapter 12 discusses the current employment situation for non-standard workers in the Nordics following the corona pandemic and crisis in Spring and Summer 2020. The corona crisis hit the Nordic economies hard when measured in terms of real GDP growth. The economic slowdown has been accompanied by rising unemployment rates, where some groups of employees, notably in tourism, retail, hotels and restaurants and large part of the performing arts and entertainment industry have been exposed to job loss – that is, sectors where non-standard workers are overrepresented. Nordic governments have launched a series of unprecedented help packages that in many respects cover a much broader group, including non-standard workers, than the kind of measures we saw during the financial crisis of 2008. Although the intentions of the Nordic governments’ help and rescue packages were to unite people by creating a safety net even for those on the outskirt of the labour market, we find that the reforms have in some instances exposed and reinforced the gaps in Nordic employment- and social protection, but more so in some Nordic countries than others. Norway, Finland and Iceland suspended to some degree existing eligibility criteria for unemployment benefits and sick pay and gave all workers, including freelancers and solo self-employed workers, access to income security in case of job loss, temporary dismissals or lost revenue from freelance or self-employed business activities. In Sweden, the national government lowered the criteria for unemployment benefits and sick pay to ease access, while Denmark was the only country where the usual criteria for accruing rights to unemployment benefits and sick pay remained unchanged with regard to past employment records and weekly working hours. Moreover, in Sweden and Denmark, temporary workers, freelancers and solo self-employed people were unable to qualify for wage compensation, temporary lay-off or short-term work schemes, which stood in contrast to Iceland. In Norway and Finland, temporary workers could, unlike freelancers and self-employed people, qualify for temporary lay-off or short-time work schemes. However, Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian freelancers and solo self-employed people could, similarly to their Icelandic and Finnish counterparts, seek other targeted support schemes to cover their lost income. Therefore, some groups of non-standard workers apparently found it more difficult to use the help and support schemes than standard workers. Thereby, it appears that the corona crisis has not only tested the safety net around non-standard workers, but also pointed to long-existing gaps in the systems, leading to innovative ad hoc policy responses in all the Nordic countries to protect non-standard workers against the losses imposed by the national governments’ lockdowns and restrictions of their business opportunities.

Chapter 13 concludes the report by summarising the findings and discussing further perspectives for policy and research. We highlight six main concluding points: 1. The overall share of NSW in the Nordics has remained relatively stable since 2000, ranging from one in four of all employed in Sweden to nearly one in three in Denmark, Norway, Finland and Iceland. 2. Each Nordic country presents a different blend of non-standard work, which to some extent also differ between sectors and companies. 3. Moving to the sector level, we find troubled waters under the still surface. The most salient changes in NSW in the Nordics seem to be concentrated within certain sectors. 4. Emerging practices of non-standard work: new challenges and possibilities. Moving to the company level, variations seem to increase and new (and often more casual) practices emerge below the surface. 5. Muddy waters and lack of data: methodological challenges when studying non-standard work. The emerging practices at company level indicate that we may be looking through muddy waters when we try to measure non-standard work, and we miss important developments – especially changes within non-standard work. In sum, our report calls for methodological development and more fine-grained data with regards to the study of NSW in the Nordics to support policymakers with updated data about ongoing change. Despite the fact that the total volume of NSW remains fairly stable, we find signs of casualisation within NSW that needs to be characterised and documented in detail. This casualisation process might involve a clustering of risks for workers and highlights the importance of adequate social security protection for non-standard workers provided either via the Nordic models of labour market regulation or/and the welfare states. 6. Regulation of NSW in light of the corona crisis: reducing or fighting insecurities. The shock effects of the corona crisis on the Nordic labour markets were a lesson to many non-standard workers as they were some of the first to lose their job or stop receiving new contracts or work assignments. The Nordic governments launched unprecedented broad help packages with the aim to cover both standard and non-standard workers, apparently with more success in some countries than others. This relates to the data problem mentioned above, but it is also closely tied to the income patterns of many non-standard workers. Many combine various forms of NSW to avoid underemployment, making it difficult to categorise, measure and target them. Regarding the future of work in the Nordic labour markets, we find different examples of how social partners address the challenges and adjust the regulation to enhance security for non-standard workers. In some instances, social partners have negotiated innovative policies into existing collective agreements, whereas in other instances politicians have introduced obligatory measures by law. However, it seems more difficult to target non-standard workers than standard workers via existing collective agreements, as many of them are not covered by a collective agreement and even more not unionised. Extension of collective agreements by law can be an instrument to tackle this challenge. Furthermore, solo self-employed workers and freelancers are difficult to cover by collective agreements due to competition laws. In consequence, some groups of non-standard workers may only be reached by legislative measures. Finally, ongoing negotiations in the EU on labour market directives targeting working conditions for non-standard workers may also feed into the Nordic discussions on non-standard work. Typically, social partners in the Nordics prefer voluntarist solutions along the lines of the Nordic collective bargaining traditions. However, this may encounter greater difficulties regarding NSW and calls for innovative responses in the Nordics.

Chapter 1 Comparative perspectives on non-standard work in the Nordics: definitions and overall trends

By: Trine P. Larsen & Anna Ilsøe

1.1 Introduction: Non-standard work in the Nordics

Non-standard work (NSW) and the associated risks of precarious employment have been subject to increased attention among policymakers, social partners and academic scholars across the Nordic countries. Numerous questions have been raised, such as will NSW be the future norm in the Nordic labour markets?, To what extent does NSW lead to more freedom and flexibility for workers or deteriorating employment conditions, and if so, for whom? How does NSW influence productivity and economic growth? And how will the sustainability of the Nordic collective bargaining model and welfare state be affected by rising disparities and segmentation between the core and the periphery of labour markets?

In this context, a growing body of literature with focus on labour market inequalities has explored the volume, characteristics and distinct types of NSW, including the regulatory framework, and the wage and working conditions under which non-standard workers are employed (Rubery et al. 2018; Ingelsrud et al. 2019; Håkansson & Isidorsson 2015). Concepts such as working poor, the precariat, bad or poor jobs and precarious employment that originate from Anglo-Saxon literature have increasingly been applied in the Nordic working life literature to capture the fragmented, insecure and unpredictable employment situation of non-standard workers across the Nordic countries (Kalleberg 2011; Rubery et al. 2018; Standing 2011; Larsen 2011). Also concepts like living wage and living hours have been used by Nordic scholars to explore the minimum income or minimum hours necessary for workers to secure a basic, but decent standard of living through employment without government subsidies (Anker 2011; Ilsøe et al. 2017). These studies find that although the Nordic labour markets in general demonstrate high wage levels, generous employment and social protection and high living standards, there are often increased risks of low wages and employment and income insecurities associated with NSW (Rasmussen et al. 2019; Jesnes 2019; Pärnänen 2017; Ilsøe 2016). Ample Nordic research also points to lower levels of health and safety, skill formation, fewer social rights and lack of institutional representation for non-standard workers (Nätti, 1993; Nergaard, 2016; Scheuer, 2017).

However, the findings/results tend to differ depending on the applied definitions and categories of NSW as well as the employee groups under examination as there exists no statistical conceptual framework that defines NSW within Nordic and international statistical standards (Frosch 2017). In this report, NSW is defined as employment other than the traditional full-time open-ended contract, which throughout the 20th century became the “standard” employment relationship and the foundation of most Nordic welfare- and labour market institutions. Therefore, any worker with a contract other than an open-ended full-time contract risks in principle lower levels of protection than their peers in standard employment (Frosch 2017).

The most common and well-described forms of NSW in the Nordic countries are part-time work, fixed-term contracts, solo self-employment and temporary agency work (TAW). However, during the last two decades, there has been a shift towards novel ways of organising work on the Nordic labour markets, where emerging forms of employment under the broad headings of zero-hour contracts, platform work, on-call work, and distinct forms of solo self-employment have become more salient. Many of these employment forms are not yet systematically documented by existing surveys and register data. In fact, various studies point out that existing studies underestimate the share of such groups as they are not well covered by for example the Labour Force Survey (LFS) or Nordic register data (Ilsøe & Larsen 2020a; Frosch 2017). Thereby, a too rough and, possibly, somewhat skewed picture of the changing employment patterns among European workers, especially non-standard workers, emerges from the LFS survey, even if it is the most comprehensive survey on employment forms in the Nordics (Frosch 2017). Thereby, we are not able to disentangle the changes going on in the composition, character and extent of casualisation within the numerically fairly stable non-standard segments of employment.

In this chapter, we focus exclusively on how the traditional forms of NSW such as part-time work, fixed-term contracts, TAW and solo self-employment have evolved within the last 20 years in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Our comparative analysis draws on the findings from the national country reports prepared by the national teams listed in the preface[1]The national teams are for Denmark (Stine Rasmussen, Trine P. Larsen, Anna Ilsøe, Per Kongshøj Madsen, Emma S. Bach); Finland (Satu Ojala, Tiina Saari, Pasi Pyöriä, Paul Jonker-Hoffrén, Jouko Nätti), Iceland (Katrin Olafsdottir, Kolbeinn Stefansson, Arney Einarsdottir), Norway (Kristine Nergaard), and Sweden (Tomas Berglund, Anna Hedenus, Kristina Håkansson, Tommy Isidorsson).. These national reports draw on data from the Danish, Finnish, Icelandic, Norwegian and Swedish LFS, which is then triangulated with secondary empirical data, policy documents, collective agreements and labour laws. The new, emerging forms of NSW that remain invisible in the LFS and Nordic register data are explored in the chapters 8–10, where company-based case studies have been used to advance our understanding of these forms of NSW.

This chapter is structured into seven sections. First, we briefly examine the recent development of traditional NSW in the five Nordic countries from 2000 to 2020. In the first section, we also examine how the various types of NSW (marginal part-time, long part-time, temporary employment and solo self-employment) vary not only across countries, but also across sectors and over time. We then examine the main characteristics of non-standard workers in the five Nordic countries. Finally, section three briefly discusses the various methodological challenges and alternative ways of analysing NSW, including the emerging forms of organising work, before summarising our main findings.

Footnotes

- ^ The national teams are for Denmark (Stine Rasmussen, Trine P. Larsen, Anna Ilsøe, Per Kongshøj Madsen, Emma S. Bach); Finland (Satu Ojala, Tiina Saari, Pasi Pyöriä, Paul Jonker-Hoffrén, Jouko Nätti), Iceland (Katrin Olafsdottir, Kolbeinn Stefansson, Arney Einarsdottir), Norway (Kristine Nergaard), and Sweden (Tomas Berglund, Anna Hedenus, Kristina Håkansson, Tommy Isidorsson).

Info box: Non-standard work – used definitions

Non-standard work is defined as employment other than the standard full-time open-ended contract. Full-time work is typically defined around what is considered the “normal” working week in the individual countries, which ranges from 37 hours per week in Denmark to 40 hours per week in Sweden, Finland and Norway, where collective agreements often operate with a lower “normal working week.

Full-time employment: To secure comparability across the Nordic countries, full-time work is considered 30+ weekly working hours, well-knowing that Eurostat and the Nordic statistic offices operate with a broader definition. Using 30 weekly hours as the threshold for defining full-time work also allow us to include for example shift workers, cleaners and care staff on open-ended contracts as their collective agreed full-time working week is typically considered 30-35 hours per week.

Info box: Forms of non-standard work examined

- Long part-time work is defined as 15–29 hours per week.

- Marginal or short part-time work is defined as less than 15 weekly working hours, even if this form of part-time work is defined differently across the Nordic region.

- Temporary employment is defined as contracts with a fixed end date and covers both fixed-term contracts and temporary agency work (TAW).

Fixed-term contract: A temporary employment contract for a fixed period such as a probation period, project assignments or substitute for employees on leave.

Temporary agency work (TAW): An employment relationship in which the employee works through an agency, but performs work on a temporary basis at a user company and under the supervision and direction of the user company.

- Solo self-employment: People not enrolled in a subordinate employer-employee relationship and without employees such as freelancers, external consultants and digital platform workers operating as independent contractors.

1.2 Non-standard work – types and recent development across the Nordic labour markets

NSW covers a broad range of employment forms that have historically co-existed alongside the full-time open-ended contract across the Nordic labour markets. In the last few decades, novel ways of organising work have become more common such as digital platform work, TAW and zero-hour contracts. Some of the more traditional forms of NSW, for instance part-time work, fixed-term contracts and solo -self-employment, have also become more prevalent in the Nordic labour markets, but more so in some countries and sectors than others. NSW accounted for around 32 per cent of all employed in Iceland compared to 31 per cent in Finland, 29 per cent in Denmark and Norway, and 26 per cent in Sweden in 2015 (fig. 1.1). Since 2008, the share of NSW has increased marginally in Finland (from 30 per cent to 31 per cent of all employed) but has slightly declined in Norway and Sweden during the same period. Denmark and Iceland have seen a more marked rise with the share of non-standard workers increasing from 26 per cent of all employed in 2000 to 29 per cent in 2015, while in Iceland 32per cent of all employed worked in NSW in 2015 compared to 28 per cent in 2015 (fig. 1.1).

Note: non-standard work is defined as marginal part-time, long part-time (15–29 hours per week), fixed-term contracts, TAW and solo self-employment.

Part-time work is the most common form of NSW across the Nordic labour markets, ranging in 2019 from 27 per cent of all employed in Norway to 25 per cent in Denmark, 24 per cent in Sweden, 22 per cent in Iceland and 17 per cent in Finland (fig. 1.2). Temporary employment that covers both fixed-term contracts and TAW is also a common form of non-standard work, but more so in Finland and Sweden than Denmark, Iceland and Norway. Around 15 per cent of all employed are temporary workers in Sweden compared to 14 per cent in Finland, 10 per cent in Denmark, 7 per cent in Norway and Iceland, respectively (fig. 1.2). Solo self-employment is the least widespread form of NSW with less than one in ten of all employed being solo self-employed in all five Nordic countries (fig. 1.2).

The share of part-time work, temporary employment and solo self-employment varies not only across countries, but also across sectors and over time – aspects that are explored below.

1.2.1 Part-time work in the Nordics – types, development and sector variations

Part-time work is widely used throughout the Nordic countries, though as mentioned earlier, more so in Norway, Denmark and Sweden, where around one in four work reduced hours (fig. 1.3). Looking across time, there have been slight changes in the share of part-time work in each Nordic country. Since 2000, part-time work has steadily increased in Finland and Denmark until 2010 and decreased in Iceland during the same period. The situation in Norway and Sweden is slightly different, where part-time work increased up until 2004 and 2009 respectively, decreasing thereafter except for a brief hike in Norway in 2018 (fig. 1.3).

The overall changes in part-time work mirror fluctuations in its distinct forms, where we in this study focus on long part-time work (defined as 15-29 weekly working hours) and marginal part-time work (less than 15 weekly working hours). Particularly marginal part-time work is often associated with increased risks of lower levels of social and employment protection (Rasmussen et al. 2019). By looking at these two types of part-time work, we find that there have been different developments in the Nordic countries, where especially Denmark stands out. Since 2000, the share of marginal part-time work has nearly doubled in Denmark, while the increases in the other Nordic countries have been markedly weaker (fig. 1.4). During the same period, the shares of long part-time employment declined in Denmark, Sweden and Norway, while the shares have slightly increased in Iceland and Finland (fig. 1.4).

Note: Marginal part-time is less than 15 hours per week, long part-time work is defined as 15-29 weekly working hours.

These figures suggest that it is mostly marginal part-time work that has increased in all five Nordic countries since 2000, and that this is particularly widespread in the service sectors. In Norway, 28 per cent work less than 15 hours per week in the creative industry, i.e. arts and entertainment, compared to nearly one in three employees in the Danish creative industry, and in the Danish hotel and restaurant sector (fig. 1.5). In Sweden and Finland, contracts of few hours are also frequently used in the creative industry accounting for 15 per cent of all jobs in the sector in Sweden and 17 per cent in Finland. In Iceland, marginal part-time work is mostly used in private services, where 19 per cent hold contracts of few hours followed by financial and insurance activities where NSW accounts for 15 per cent of all jobs in the sector (fig. 1.5).

Note: For Iceland, the Hotel and restaurant sector is a merged category also covering transport, retail and wholesale sector due to low numbers.

Long part-time work is also widespread in the Nordic service sector and often twice as high as the aggregated national figures, which vary from 8 per cent in Sweden to 12 per cent in Norway (fig. 1.4 and 1.6). In Norway, Denmark and Iceland nearly one in five jobs in the hotel and restaurant sector are long part-time, compared to 17 per cent in Finland and 16 per cent in Sweden. Long part-time work is also common in the Nordic creative industry, where the share of long part-time work ranges from 13 per cent in DK to 16 per cent in Sweden and Norway (fig. 1.6).

Note: Iceland’s hotel and restaurant sector is a merged category also covering the transport, retail and wholesale sector due to low numbers.

In sum, the overall changes in part-time work, especially marginal part-time work, has increased in Denmark, Iceland and Finland between 2000 and 2015, while the overall share of part-time work has decreased slightly in Sweden and Norway during the same period. The changes in part-time work seems to be closely tied to cyclical swings in the labour market. For example, Finland, Denmark and Iceland saw a downturn in the labour market when the financial crisis hit the Nordic labour markets in 2008, leading subsequently to a rise in part-time work, but not necessarily mirroring a decline in full-time employment, except for Finland. The share of full-time employment when measured in actual numbers slightly decreased between 2008 and 2011 in Iceland and between 2008 and 2012 in Denmark, but then started to increase, although less rapidly than part-time work. In Finland, the share of full-time employment continued to decline during the same period, while Norway and Sweden saw a steady job growth in both part-time and full-time positions between 2008 and 2019 (Eurostat 2020c). However, Nordic companies’ usage of part-time work varies considerably across sectors. In the hotel and restaurant sector, more than one in two jobs are either short or long part-time in Denmark, compared to 40 per cent of all jobs in the Norwegian hotel and restaurant sector and one in four jobs in the Swedish and Finnish hotel and restaurant sector. The Nordic creative sector also relies extensively on part-time work and thus in some sectors, part-time work – covering both long and short hours – are nearly three or in some instances four times higher than the national average in each of the Nordic countries (fig. 1.4; 1.5; 1.6). These sector variations as to the type and levels of NSW become even more evident when examining distinct forms of temporary employment.

1.2.2 Temporary employment in the Nordics – types, development and sector variations

Temporary employment is yet another form of NSW that is common across the Nordic countries. It is an umbrella term that covers both fixed-term contracts and TAW, as the latter is not measured separately in some of the Nordic LFS data. Most temporary jobs are fixed-term contracts since TAW continues to remain marginal across the Nordic labour markets ranging from 1.5-2 per cent of all employees in Norway, 1.3 per cent in Sweden, 1.9 per cent in Finland to 0.6 per cent in Denmark (Eurostat 2020d; Alsos & Evans 2018). In this context, it is important to note that the figures on TAW include TAW holding temporary contracts as well as open-ended contracts in Finland, Sweden and Norway, while in Iceland and Denmark, all TAWs are employed on temporary contracts.

Since 2000, the share of temporary workers has remained fairly stable across the Nordic region, except for Iceland and Sweden (fig. 1.7). In Sweden, the share of temporary workers increased from 13 per cent of all employed in 2000 to 15 per cent in 2019. In Iceland, the share of temporary workers increased from 4 per cent of all employees in 2000 to 12 per cent in 2013, when it peaked and has during the subsequent period of strong employment growth continued to decline and stood at 7 per cent in 2019 (fig. 1.7). Thus, over time, Icelandic employers appear to have shifted their usage of temporary employment from a pattern fairly similar to Swedish and Finnish employers in the post-crisis years to an employment pattern that is more like their Danish (10 per cent are temporary workers) and Norwegian (7 per cent are temporary workers) counterparts in 2019. Notable is also the hike in temporary employment in Denmark in 2016, but these changes are merely due to problems with the data quality in the Danish LFS from 2016 rather than reflecting a genuine increase in the share of temporary employment.[1]In 2016, Statistics Denmark decided to outsource the data collection for the LFS to a new private supplier and that caused problems with the data quality in the Danish LFS in 2016 (Statistics Denmark 2019e). By 2019, temporary employment accounted for around 14 per cent of all employed in Finland and 15 per cent Sweden compared to 10 per cent in Denmark, 9 per cent in Iceland and 7 per cent in Norway (fig. 1.7).

Footnotes

- ^ In 2016, Statistics Denmark decided to outsource the data collection for the LFS to a new private supplier and that caused problems with the data quality in the Danish LFS in 2016 (Statistics Denmark 2019e).

Note:

Most temporary contracts typically have a duration of less than 6 months. In Iceland, nearly nine out of ten temporary workers hold a temporary contract of less than 6 months compared to nearly three in four temporary workers in Finland (table 1.1). Also, in Sweden and Denmark, short-term contracts are common with nearly one in two of all temporary contracts being less than 6 months in 2018. However, Norway and Denmark both stand out similarly in that only 15 per cent of temporary contracts in Norway and 13 per cent of temporary contracts in Denmark are less than 3 months compared to 41 per cent in Iceland, 33 per cent in Finland and 28 per cent in Sweden (table 1.1). These figures indicate that a large group of temporary workers hold contracts of less than six months or even shorter, and their share has increased in all the Nordic countries, except perhaps for Norway, since 2000. In 2000, around 58 per cent of temporary workers held contracts of less than six months in Norway compared to 48 per cent in Iceland, 45 per cent in Finland, 43 per cent in Sweden and 32 per cent in Denmark (authors’ own calculation based on LFS data published by Eurostat 2020e). The marked decline in Norway may partly be linked to the increased non-response rate (table 1.1).

| Less than 3 months | 4–6 months | 12+ months | No response | Total | |

| Denmark | 13 | 32 | 55 | : | 100 |

| Finland | 33 | 48 | 17 | 2 | 100 |

| Sweden | 28 | 27 | 26 | 18 | 100 |

| Iceland | 41 | 51 | : | 9 | 100 |

| Norway | 15 | 17 | 26 | 42 | 100 |

The share of temporary employment varies not only across the Nordic countries, but also across sectors. In some sectors, such as education in Finland and the category Other Services (for example hairdressing or repair of computers (Eurostat 2008: 88) in Iceland, one in four of all employees hold temporary contracts. In Sweden, these numbers are even higher in sectors such as hotels and restaurants, the creative industry and administration with almost a third of employees being temporary workers. In Denmark and Norway, the incidence of temporary jobs is markedly lower even for the three sectors with the largest share of temporary employment (13 per cent) (fig. 1.8).

*Note for Iceland, Administration and services is a merged category that covers public administration, defence, health and social work due to low numbers.

In sum, these findings suggest that Swedish, Finnish and Icelandic employers are more likely to draw on temporary contracts to secure flexibility than their Danish and Norwegian counterparts, who in turn tend to rely more on other forms of non-standard work, especially marginal- and long part-time work as seen in the previous section. In fact, the share of temporary workers in some Icelandic, Swedish and Finnish sectors are twice as high as the national aggregated data, while in Denmark and Norway, the incidence of temporary employment in distinct sectors seem to only be slightly higher than the national average (fig. 1.7 and 1.8). However, overall changes in temporary employment seem, similarly to the fluctuations in part-time work, to some extent to mirror cyclical changes in the labour market. Icelandic employers were more likely to rely heavily on temporary employment in the post-crisis years (2008- 2012) and the figure has declined in the aftermath of the financial crisis. In Finland and Sweden, the number of temporary workers declined when the financial crisis hit the Nordic labour markets, but then started to marginally increase in the first few years after the crisis (fig. 1.7).

1.2.3 Solo self-employment

Solo self-employment is a different category of NSW as such workers are typically considered micro-companies but are without employees and tend to offer their services to only one or few other companies. Since 2000, solo self-employment has become more prevalent in Finland, but has declined in Norway, Sweden and more rapidly in Iceland. In Denmark, the share of solo self-employment continued to increase up until 2012 and has since then marginally decreased: 9 per cent of all employed were solo self-employed in Finland in 2019 compared to 8 per cent in Iceland, 6 per cent in Sweden and 5 per cent in Denmark and Norway, respectively (fig. 1.9).

Agriculture, forestry and fishery is by far the sector with the most solo self-employed people, ranging from 21 per cent in Denmark to 51 per cent in Finland. This is nearly five times higher than the national average for the Nordic labour markets (fig. 1.9 & 1.10). Another sector with high shares of solo self-employment is the category Other Services, where nearly one in five of all employed are solo self-employed in Finland, Iceland and Sweden compared to 14 per cent in Norway and 12 per cent in Denmark in 2015. Also, the creative industry has many solo self-employed, most notably in Norway and Finland where one in five workers is solo self-employed compared to 17 per cent in the Swedish creative sector (fig. 1.10).

1.3 Nordic non-standard workers and their characteristics

As in other European countries, women, young people - especially students -, foreign born, older workers aged 65+ and lower skilled workers tend to be overrepresented among non-standard workers also in the Nordic countries. However, important variations exist depending on the type of NSW under consideration as well as across countries and sectors. To capture these differences, each national team conducted logistic regression analyses for each of the four employment types, where they controlled for gender, age, ethnicity, educational attainment, multiple jobholding and sector (see appendix). The regression analyses indicated that the likelihood of taking up part-time work, temporary employment or self-employment was higher among some groups than others. We also find that NSW may be a choice for some, while others involuntarily have to accept non-standard work.

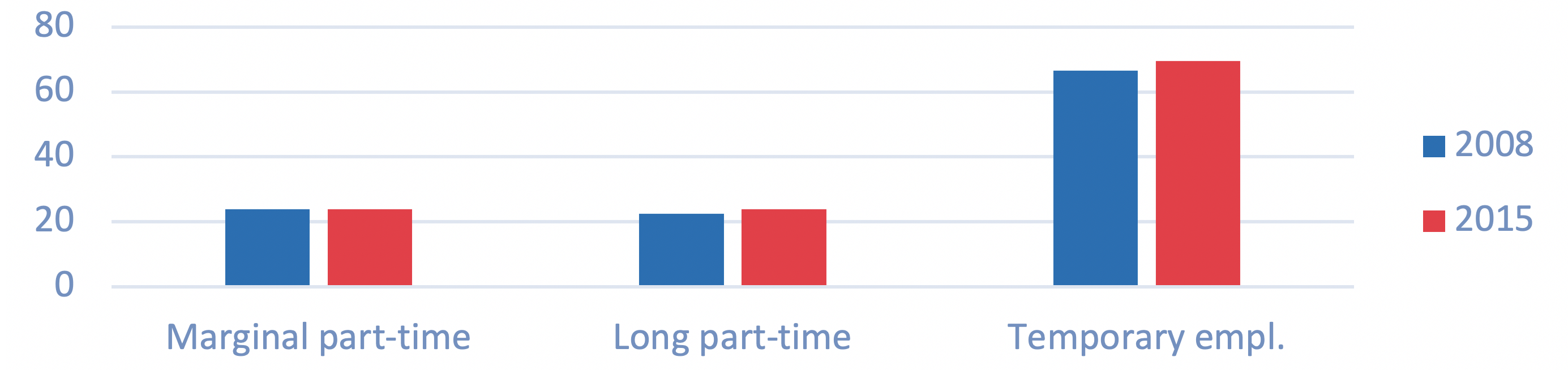

Marginal part-time work seems to attract especially young people aged 15-29 years – typically students – and older workers (65+). Women, foreign-born and lower skilled workers are also overrepresented among marginal part-time workers. Many with contracts of few hours tend to combine two or more jobs, suggesting that multiple job holding is often a way to make ends meet for marginal part-time workers (appendix). Their main reason for taking up marginal part-time work is for many a voluntary choice, especially in Denmark and Iceland (fig. 1.11). However in Finland, the share of people that involuntarily accept a contract of few hours has increased from 17 per cent in 2008 to 21 per cent in 2015, which may be closely tied to the economic downturn in the Finnish labour market that lasted until 2015/2016 (fig. 1.11). In the other four Nordic countries, the share of involuntary part-time work has remained fairly stable, but important cross-country variations exist: In Sweden, one in four marginal part-time workers would prefer a full-time job compared to 16 per cent in Norway, 5 per cent in Denmark and 4 per cent in Iceland (fig.1.11).

Note: Figures for involuntary solo self-employment are only available for 2017 and this is a merged category covering inability to find a job as an employee, had not planned or wanted to work as solo self-employed and their former employer had requested that they worked as solo self-employed.

Long part-time work is particularly common among students followed by older people aged 65 or more in Finland, Norway, Iceland and Denmark. In Sweden, the likelihood of holding long part-time work among older workers (65+) is as high as among students (appendix). Recent pension reforms, involving various financial incentives, changes in the statutory retirement age and distinct work arrangements to retain older workers in paid work may account for the large share of older people among the group of part-time workers in the Nordic labour markets (Ojala et al. 2020). Although older people similarly to students tend to be overrepresented among part-time workers, we also find that other groups such as women, lower skilled and foreign-born individuals are more likely to take up long part-time work and many often hold multiple jobs. Working reduced hours is a voluntary decision for many as the incidence of involuntary long part-time ranges from 12 per cent in Iceland to 33 per cent in Finland in 2015. The share of involuntary long part-time work has increased somewhat in all five Nordic countries since 2008 (fig. 1.11). Among Danish and Icelandic part-time workers, particularly those working between 15- 29 hours per week, a growing number choose to work reduced hours due to own disability or illness (Rasmussen et al. 2020; Olafsdottir et al. 2020).

Temporary employment is more prevalent among young people and students in all five Nordic countries. In Sweden and Norway, older workers (65+) stand out as a group among temporary workers. In all five countries, we also find a slight overrepresentation of women, lower skilled, foreign-born individuals and multiple jobholders (appendix). Many temporary workers involuntarily accept temporary jobs, especially in Finland, Sweden and Norway, and their numbers have grown since 2008. Around 70 per cent of temporary workers in Sweden would prefer a permanent job compared to 70 per cent in Finland, 67 per cent in Norway, 43 per cent in Denmark and 11 per cent in Iceland (fig. 1.11).

Solo self-employment is more likely a career path among older male workers in all five Nordic countries and they often work in certain sectors such as agriculture, forestry and fishery (fig. 1.10). Solo self-employment is also common among students in Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Iceland (appendix). Other characteristics for this group are that many tend to be lower skilled, and at least some of the solo self-employed supplement their income with other jobs (appendix). Their main reasons for pursuing a career as solo self-employed have recently been explored in the LFS’s 2017 ad hoc module, which indicated that the vast majority of solo self-employed have voluntary opted for such a career. Many prefer solo self-employment to gain increased working time flexibility, especially in Norway (30 per cent of all solo self-employed), Iceland (22 per cent) and Sweden (20 per cent), while this only applied to 12 per cent in Finland and 14 per cent in Denmark. Others saw solo self-employment as a suitable opportunity, especially in Denmark, Sweden, Iceland and Finland, where more than one in five listed this as their main reason for taking up solo self-employment compared to 11 per cent in Norway (authors’ own calculations of LFS data in Eurostat 2017a). In fact, hardly any individuals had accepted solo self-employment involuntarily in Iceland compared to 14 per cent in Finland, 13 per cent in Norway, 11 per cent Sweden and 8 per cent in Denmark (fig. 1.11).

In sum, involuntary NSW has increased in the five Nordic countries during the last two decades. It is particularly prominent in Sweden, Finland and Norway and lowest in Denmark and Iceland. The share of people that have had to accept involuntary non-standard jobs varies across countries and types of NSW. Solo self-employment and part-time work are for many a voluntary choice, while this is less so in the case of temporary jobs. Older workers, young people (students in particular), women and foreign-born individuals are more likely to take up part-time and temporary employment, whilst men, often older, are more likely to pursue a career as solo self-employed in all five Nordic countries.

1.4 Methodological challenges and alternative studies on emerging forms of non-standard work

A growing body of international literature has studied NSW and often points to the methodological challenges that are tied to analysing the new, emerging forms of NSW such as zero-hour contracts, on-call work and platform work (Frosch 2017; Ryan et al. 2019). First and foremost, there exists no common statistical conceptual framework that defines NSW within the Nordic and international statistical standards, and thus NSW are typically ambiguously defined (Frosch 2017). The share and types of NSW tend therefore to differ depending on the used definitions and categories of non-standard as well as the employee groups under examination. For example, the OECD (2020a) in its recent Employment Outlook defines NSW as temporary employment, part-time work and solo self-employment. Implicitly this presumably indicates that the OECD regards the emerging forms of NSW such as zero-hour contracts and on call work as sub-groups or variants of the former categories of non-standard work. Similarly, research tends to define part-time work differently, where some studies and statistical offices such as Eurostat and the Nordic statistical offices operate with a rather broad definition of part-time work, both including longer hours up to what is nationally considered the normal weekly working hours. The “normal” weekly working week is considered 37 hours per week in Denmark, 40 hours in Norway, Sweden, Iceland and Finland by law, but with important inter-sectoral variations as most, if not all, collective agreements operate with lower thresholds for what is considered full-time work (see country chapters 3–7). By contrast, the OECD’s threshold for part-time work is, similar to the definition adopted in this report, 30 weekly working hours and thus the OECD’s figures on part-time work are slightly more conservative than the figures by for example Eurostat (OECD 2020a). In addition, the definitions on marginal part-time work tend to vary across the Nordic countries with the notion of contracts of few hours, ranging from less than 19 weekly working hours to 15 weekly working hours or even lower in some instances (see country chapters 3–7).

Also, temporary employment is typically measured differently in the Nordic countries and tends to be an umbrella term for both fixed-term employment and TAW in most surveys. In fact, in some of the Nordic LFS data, TAW is not measured separately, even if research indicates that the working conditions, employment- and social protection of TAW often differ considerably from fixed-term workers, who often have longer employment contracts (Alsos & Evans 2018; Mailand and Larsen 2018). There are also challenges associated with analysing solo self-employment using the Nordic LFS data, since some forms of solo self-employment are not covered by LFS such as workers operating in the grey-zones of being employees or own-account workers (Frosch 2017). In fact, many of the emerging forms of NSW such as on-call work, zero-hour contracts and platform work and posted workers are not yet systematically documented by existing surveys and register data. Ample research thus indicates that existing surveys underestimate the range of such groups as they are not well covered by the LFS or Nordic register data (Ilsøe & Larsen 2020a; Frosch 2017; see country chapters 3–7). Many of these groups also tend to be multiple jobholders often with two or more jobs, which is not captured by for example the LFS, as it only distinguishes between primary and secondary jobs. We also find that many of the traditional and emerging forms of NSW tend to overlap, where for example solo self-employed workers work reduced hours or a TAW holds an open-ended contract, but work reduced hours, which poses further methodological challenges as to measuring these forms of work. Therefore, only some employment patterns among European workers, especially non-standard workers, are documented by the LFS survey, even if it is the most comprehensive survey on employment forms in the Nordics. Access to better data on distinct forms of NSW is pivotal to better apprehend the dynamics and changes going on outside the core of the Nordic labour markets. This is all the more warranted as many national governments and social partners, including the Nordic, rely on LFS data and register data when developing new social- and labour market policies.

When it comes to the categories of on-call work, zero-hour contracts, platform work and posted workers that have emerged or increased in recent years, there are also important differences in how these concepts are defined within the literature. Thus, the empirical results as to their numbers vary considerably from one study to another and point to the need for comparable international data based on a similar framework.

On-call work refers to ad hoc working arrangements with no predictable fixed hours and may involve very few hours or no guaranteed hours. The definition of on-call work differs across the Nordic countries and may in some instances include zero-hour contracts, i.e. employment contracts with no or few guaranteed hours (see below). On-call work is not regularly measured in the Nordic LFS and will presumably be subsumed under part-time or temporary work. However, on-call work was part of an ad hoc module in the LFS survey in 2004, where 1.2 per cent of all employees in Denmark, 1.9 per cent in Finland, 2 per cent in Sweden and 3.6 per cent in Norway reported that they only work when called in. The share of workers with on-call arrangements were statistically insignificant in Iceland (Frosch 2017; Eurostat 2004: lfso_04oncwisna). Recent studies including our qualitative chapters suggest that on-call work has become more widespread in the Nordic countries, especially in sectors such as eldercare and private services including retail, hotels and restaurants, etc. (Bach et al. 2020; Hedenus & Rasmussen 2020).